Archaeology at the River's Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

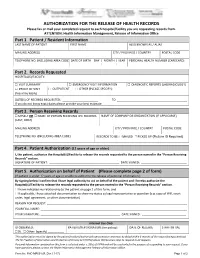

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

Lillooet-Lytton Tourism Diversification Project

LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM PROJECT 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ..................................................................................4 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Terms of Reference............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Study Area Description...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Local Economic Challenges............................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TOURISM.....................................................................9 2.1 Tourism in British Columbia............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Nature-Based Tourism and Rural BC............................................................................................................ -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

Understanding Our Lives Middle Years Development Instrumentfor 2019–2020 Survey of Grade 7 Students

ONLY USE UNDERSTANDING OUR LIVES MIDDLE YEARS DEVELOPMENT INSTRUMENTFOR 2019–2020 SURVEY OF GRADE 7 STUDENTS BRITISH COLUMBIA You can preview the survey online at INSTRUCTIONALSAMPLE SURVEY www.mdi.ubc.ca. NOT © Copyright of UBC and contributors. Copying, distributing, modifying or translating this work is expressly forbidden by the copyright holders. Contact Human Early Learning Partnership at [email protected] to obtain copyright permissions. Version: Sep 13, 2019 H18-00507 IMPORTANT REMINDERS! 1. Prior to starting the survey, please read the Student Assent on the next page aloud to your students! Students must be given the opportunity to decline and not complete the survey. Students can withdraw anytime by clicking the button at the bottom of every page. 2. Each student has their own login ID and password assigned to them. Students need to know that their answers are confidential, so that they will feel more comfortable answering the questions honestly. It is critical that they know this is not a test, and that there are no right or wrong answers. 3. The “Tell us About Yourself” section at the beginning of the survey can be challenging for some students. Please read this section aloud to make sure everybody understands. You know your students best and if you are concerned about their reading level, we suggest you read all of the survey questions aloud to your students. 4. The MDI takes about one to two classroom periods to complete.ONLY The “Activities” section is a natural place to break. USE Thank you! What’s new on the MDI? 1. We have updated questions 5-7 on First Nations, Métis and Inuit identity, and First Nations languages learned and spoken at home. -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

BC Hydro ILM Amendment Application.Pdf

July 4, 2012 INTERIOR TO LOWER MAINLAND TRANSMISSION (ILM) PROJECT Spuzzum Alignment EAC Amendment Application Submitted to: BC Hydro Suite 1100, Four Bentall Centre 1055 Dunsmuir Street P.O. Box 49260 Vancouver, B.C. V7X 1V5 Reference Number: 0914220018-500-R-Rev0 Distribution: REPORT 2 Copies - BC Hydro 2 Copies - BC Environmental Assessment Office 2 Copies - Golder Associates Ltd. ILM PROJECT SPUZZUM ALIGNMENTEAC AMENDMENT APPLICATION Executive Summary BC Hydro has undertaken studies and submitted this Environmental Assessment Certificate (EAC) Amendment Application to assess the potential incorporation of the Spuzzum Realignment into the Interior to Lower Mainland Transmission (ILM) Project, a new 500 kilovolt (kV) Alternating Current (AC) overhead electric transmission line from Nicola Substation (NIC), near Merritt, to Meridian Substation (MDN) in Coquitlam. An EAC for the ILM Project was received on June 3, 2009 which included an alignment within the Fraser Canyon through Nodes F-F1-G1-H which would mainly be a new alignment outside of existing BC Hydro Right-of-Way (ROW) (Figures 1 and 2). The proposed Spuzzum Realignment would be within an existing BC Hydro ROW parallel to Circuit 5L41. The Spuzzum Realignment was not part of the ILM Project Alignment permitted in 2009; however, it was studied as part of the environmental assessment. Since the EAC was issued in 2009, BC Hydro has reached an agreement with the Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council (NNTC) on the ILM Project which has permitted consideration of the Spuzzum Realignment. The new line would be constructed within an existing ROW corridor through the following Spuzzum First Nation reserve lands: Papsilqua IR 2 and 2A; and Spuzzum IR 1 and 1A. -

The Cariboo Wagon Road

THE CARIBOO WAGON ROAD he success of the Cariboo goldfields necessitated the further Timprovement of the roads to the Cariboo. In May 1862, Colonel Richard C. Moody advised Governor James Douglas that the Yale to Cariboo route through the Fraser Canyon was the best to adapt for the general development of the country and that it was imperative its construction start at once. The governor concurred and it was decided that the road would be a full 18-feet wide in order to accommodate wagons going and coming from the goldfields and thus it came to be known as the Cariboo Wagon Road. The builders were to be paid large cash subsidies as work progressed and upon completion of their sections were to be granted permission to collect tolls from the travelers for the following 5 years. Captain John Marshall Grant of the Royal Engineers, with a force of sappers, miners, and civilian labor, was to construct the first six miles out of Yale, while Thomas Spence was to extend the road the next seven miles to Chapman’s Bar, at a cost of $47,000. From here, Joseph William Trutch, Spence’s partner, was to tackle the section to a point that would become Boston Bar, a distance of 12 miles, at a cost of $75,000. From here, Spence would continue the road to Lytton. Walter Moberly, a successful engineer, with Charles Oppenheimer, a partner in the great mercantile firm ROYAL ENGINEER'S BUCKLE & BUTTONS. COURTESY WERNER KASCHEL of Oppenheimer Brothers, and Thomas B. Lewis accepted the challenge to build the section from Lytton until the road joined a junction with the wagon road to be built by Gustavus Blin Wright and John Colin Calbreath from Lillooet to Watson’s stopping house. -

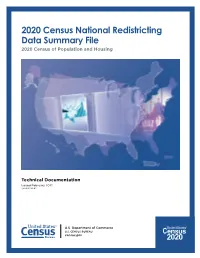

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing Technical Documentation Issued February 2021 SFNRD/20-02 Additional For additional information concerning the Census Redistricting Data Information Program and the Public Law 94-171 Redistricting Data, contact the Census Redistricting and Voting Rights Data Office, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-4039. For additional information concerning data disc software issues, contact the COTS Integration Branch, Applications Development and Services Division, Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-8004. For additional information concerning data downloads, contact the Dissemination Outreach Branch of the Census Bureau at <[email protected]> or the Call Center at 1-800-823-8282. 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Issued February 2021 2020 Census of Population and Housing SFNRD/20-01 U.S. Department of Commerce Wynn Coggins, Acting Agency Head U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Suggested Citation FILE: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Technical Documentation Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Dr. Ron Jarmin, Deputy Director and Chief Operating Officer Albert E. Fontenot, Jr., Associate Director for Decennial Census Programs Deborah M. Stempowski, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Operations and Schedule Management Michael T. Thieme, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Systems and Contracts Jennifer W. Reichert, Chief, Decennial Census Management Division Chapter 1.