University of Hawn! Ubraay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

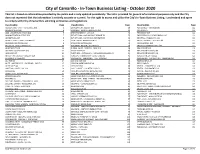

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Glossary.Herbst.Bali.1928.Kebyar

Bali 1928 – Volume I – Gamelan Gong Kebyar Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busungbiu by Edward Herbst Glossary of Balinese Musical Terms Glossary angklung Four–tone gamelan most often associated with cremation rituals but also used for a wide range of ceremonies and to accompany dance. angsel Instrumental and dance phrasing break; climax, cadence. arja Dance opera dating from the turn of the 20th century and growing out of a combination of gambuh dance–drama and pupuh (sekar alit; tembang macapat) songs; accompanied by gamelan gaguntangan with suling ‘bamboo flute’, bamboo guntang in place of gong or kempur, and small kendang ‘drums’. babarongan Gamelan associated with barong dance–drama and Calonarang; close relative of palégongan. bapang Gong cycle or meter with 8 or 16 beats per gong (or kempur) phrased (G).P.t.P.G baris Martial dance performed by groups of men in ritual contexts; developed into a narrative dance–drama (baris melampahan) in the early 20th century and a solo tari lepas performed by boys or young men during the same period. barungan gdé Literally ‘large set of instruments’, but in fact referring to the expanded number of gangsa keys and réyong replacing trompong in gamelan gong kuna and kebyar. batél Cycle or meter with two ketukan beats (the most basic pulse) for each kempur or gong; the shortest of all phrase units. bilah Bronze, iron or bamboo key of a gamelan instrument. byar Root of ‘kebyar’; onomatopoetic term meaning krébék, both ‘thunderclap’ and ‘flash of lightning’ in Balinese, or kilat (Indonesian for ‘lightning’); also a sonority created by full gamelan sounding on the same scale tone (with secondary tones from the réyong); See p. -

THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK

ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK N I H T O DUSIT AY EXP Y THANON L RE O SSWA H PHR 5 A H A PINKL P Y N A PRESSW O O N A EX H T Thonburi Democracy Station Monument 2 THAN BANGLAMPHU ON PHE 1 TC BAMRUNG MU HABURI C ANG h AI H 4 a T o HANO CHAROEN KRUNG N RA (N Hualamphong MA I EW RAYAT P R YA OAD) Station T h PAHURAT OW HANON A PL r RA OENCHI THA a T T SU 3 SIAM NON NON PH KH y a SQUARE U CHINATOWN C M HA H VIT R T i v A E e R r X O P E N R 6 K E R U S N S G THAN DOWNTOWN W A ( ON RAMABANGKOK IV N Y E W M R LO O N SI A ANO D TH ) 0 1 km TAKSIN BRI DGE 1 Ratanakosin 3 Chinatown and Pahurat 5 Dusit 2 Banglamphu and the 4 Thonburi 6 Downtown Bangkok Democracy Monument area About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The colour section is designed to give you a feel for Bangkok, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The city chapters cover each area of Bangkok in depth, giving comprehensive accounts of all the attractions plus excursions further afield, while the listings section gives you the lowdown on accommodation, eating, shopping and more. -

Legends of the Golden Land the Road

The University of North Carolina General Alumni Association LLegendsegends ooff thethe GGoldenolden LLandand aandnd tthehe RRoadoad ttoo MMandalayandalay with UNC’s Peter A. Coclanis February 10 to 22, 2014 ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dear Carolina Alumni and Friends: Myanmar, better known as Burma, has recently re-emerged from isolation after spending decades locked away from the world. Join fellow Tar Heels and friends and be among the fi rst Americans to experience this golden land of deeply spiritual Buddhist beliefs, old world traditions and more than one million pagodas. You will become immersed in the country’s rich heritage, the incredible beauty of its landscape and the warmth of friendly people who take great pride in welcoming you to their ancient and enchanting land. Breathtaking moments await you amid the lush greenery and golden plains as you discover great kingdoms that have risen and fallen through thousands of years of history. See the legacy of Britain’s former colony in its architecture and tree-lined boulevards, and the infl uences of China, India and Thailand evident in the art, dance and dress of Myanmar today. Observe and interact with skilled artisans who practice the traditional arts of textile weaving, goldsmithing, lacquerware and wood carving. Meet fascinating people, local experts and musicians who will enhance your experience with educational lectures and insightful presentations. And, along the streets and in the markets you will sense the metta bhavana, the culture of loving kindness that the Burmese extend to you, their special guest. This comprehensive itinerary features colonial Yangon, the archaeological sites of Bagan, the palace of Mandalay and the exquisite Inle Lake, with forays along the fabled Irrawaddy River. -

27Th May 2021

27th May 2021 Super moon Moon had nearest approach to Earth on May 26, and therefore appeared to be the closest and largest Full Moon or “supermoon” of 2021. Today’s celestial event coincides with this year’s only total lunar eclipse, the first since January 2019. Significantly, a supermoon and a total lunar eclipse have not occurred together in nearly six years. What is a supermoon? Supermoon occurs when the Moon’s orbit is closest to the Earth at the same time that the Moon is full. The term supermoon was coined by astrologer Richard Nolle in 1979. As the Moon orbits the Earth, there is a point of time when the distance between the two is the least (called the perigee when the average distance is about 360,000 km from the Earth) and a point of time when the distance is the most (called the apogee when the distance is about 405,000 km from the Earth). Now, when a full Moon appears at the point when the distance between the Earth and the Moon is the least, not only does it appear to be brighter but it is also larger than a regular full moon. In a typical year, there may be two to four full supermoons and two to four new supermoons in a row. About a month ago on April 26, there was another full moon, but the supermoon that witnessed on May 26 was closer to the Earth by a margin of 0.04%. What happened on May 26? On May 26, two celestial events will take place at the same time. -

Download Download

89 IDENTITY OF THAI-CHINESE IN MUEANG DISTRICT, LAMPANG PROVINCE 1อัตลักษณ์ของชาวไทยเชื้อสายจีนในอ าเภอเมือง จังหวัดล าปาง Nueakwan Buaphuan* 1 1 Lecturer, Lampang Rajabhat University *Corresponding author: [email protected] เหนือขวัญ บัวเผื่อน*1 1อาจารย์ มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏล าปาง *ผู้รับผิดชอบบทความ : [email protected] Abstract The research aimed to study Thai-Chinese identity in Muang District, Lampang Province, regarding ethnicity, history, traditional and cultural expression, and behavioral expression. Used a qualitative methodology that included studying-documents, interviews, and focus group discussions on studying a sample of experts and Thai-Chinese families. The data were analyzed by content analysis. The result was summarized as follows: 1) Cause their migration from China to Muang District, Lampang Province was poverty and escaped the war. 2) Their migration routes were two routes. The first route from Hainan Island, Koh Samui in Surat Thani Province, Other Provinces (such as Bangkok, Nakhon Sawan, Chai Nat, Nakhon Ratchasima), Lampang Province. The Second route from Guangdong and Fujian, Vietnam, Khlong Toei (Bangkok), Lampang Province. 3) Their ethnicity divided into three ethnics were Hainan, Cantonese-Chaozhou, and Hakka. 4) Traditional and cultural expression, namely, constructing shrines, worshiping ancestors, a ritual in respecting and worshiping the Chinese and Buddha deities, changing the cremation ceremony from burial to cremation, usage Thai as the mother tongue, and embellishing Chinese lanterns and characters -

A Simultaneous-Equation Model of the Determinants of the Thai Baht/U.S

A SIMULTANEOUS-EQUATION MODEL OF THE DETERMINANTS OF THE THAI BAHT/U.S. DOLLAR EXCHANGE RATE Yu Hsing, Southeastern Louisiana University ABSTRACT This paper examines short-run determinants of the Thai baht/U.S. dollar (THB/ USD) exchange rate based on a simultaneous-equation model. Using a reduced form equation and applying the EGARCH method, the paper fnds that the THB/ USD exchange rate is positively associated with the real 10-year U.S. government bond yield, real U.S. exports to Thailand, the real U.S. stock price and the expected exchange rate and negatively infuenced by the real Thai government bond yield, real U.S. imports from Thailand, and the real Thai stock price. JEL Classifcation: F31 INTRODUCTION The choice of exchange rate regimes, overvaluation of a currency, and global fnancial crises may affect the behavior of an exchange rate. Before the Asian fnancial crisis, the Thai baht was pegged to a basket of major currencies and was substantially over-valued. Due to speculative attacks and running out of foreign reserves, the Thai government gave up pegging of major currencies and announced the adoption of a foating exchange rate regime on July 2, 1997. As a result, the Thai baht had depreciated as much as 108.74% against the U.S. dollar. In the recent global fnancial crisis, the Thai baht had lost as much as 13.76% of its value versus the U.S. dollar. While a depreciating currency is expected to lead to more exports, it would cause less imports, higher domestic infation, decreasing international capital infows, rising costs of foreign debt measured in the domestic currency, and other related negative impacts. -

Genetic Characterization of Chikungunya Virus in Field-Caught Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes Collected During the Recent Outbreaks in 2019, Thailand

pathogens Article Genetic Characterization of Chikungunya Virus in Field-Caught Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Collected during the Recent Outbreaks in 2019, Thailand Proawpilart Intayot 1, Atchara Phumee 2,3 , Rungfar Boonserm 3, Sriwatapron Sor-suwan 3, Rome Buathong 4, Supaporn Wacharapluesadee 2, Narisa Brownell 3, Yong Poovorawan 5 and Padet Siriyasatien 3,* 1 Medical Science Program, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 2 Thai Red Cross Emerging Infectious Diseases-Health Science Centre, World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training on Viral Zoonoses, Chulalongkorn Hospital, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 3 Vector Biology and Vector Borne Disease Research Unit, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 4 Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand 5 Center of Excellence in Clinical Virology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2256-4387 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 1 August 2019; Published: 2 August 2019 Abstract: Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne virus belonging to the genus Alphavirus. The virus is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected female Aedes mosquitoes, primarily Aedes aegypti. CHIKV infection is spreading worldwide, and it periodically sparks new outbreaks. There are no specific drugs or effective vaccines against CHIKV. The interruption of pathogen transmission by mosquito control provides the only effective approach to the control of CHIKV infection. Many studies have shown that CHIKV can be transmitted among the Ae. aegypti through vertical transmission. The previous chikungunya fever outbreaks in Thailand during 2008–2009 were caused by CHIKV, the East/Central/South African (ECSA) genotype. -

68Th Annual Report Chapter VI. Exchange Rates and Capital Flows

VI. Exchange rates and capital flows Highlights In 1997 and early 1998 current and prospective business cycle developments in the three largest economies continued to dominate interest rate expectations as well as the movements of the dollar against the yen and the Deutsche mark. The yen showed more variability than the mark as market participants revised their views regarding the momentum of the Japanese economy. As in 1996, the dollar’s strength served to redistribute world demand in a stabilising manner, away from the full employment economy of the United States to economies that were still operating below potential. A question remains as to whether the US current account deficit, which is expected to widen substantially as a result of exchange rate changes and the Asian crisis, will prove sustainable given the continuing build- up of US external liabilities. Under the influence of several forces, large currency depreciations spread across East Asia and beyond in 1997. Apart from similarities in domestic conditions, common factors were the strength of the dollar, competition in international trade, widespread shifts in speculative positions and foreign investors’ withdrawal of funds from markets considered similar. The fall in output growth and wealth in Asia depressed commodity and gold prices, thereby putting downward pressure on the Canadian and Australian dollars. Against the background of a strong US dollar, most European currencies proved stable or strengthened against the mark. As fiscal policies and inflation converged, forward exchange rates and currency option prices anticipated the euro over a year before the scheduled introduction of monetary union. Already in 1997, trading of marks against the other currencies of prospective monetary union members had slowed. -

Study Material 2

Now we are at the second module of the Thailand E-Learning Program. This module explains about the popular destinations which include Bangkok, Kanchanaburi, Hua Hin, Pattaya, Rayong and Trat. This will help you provide with detailed information about distance and transportation, where to go, things to do, new updates and suggested itinerary ideas, so your customers will be fully prepared and most satisfied. Course Process Part 1 Part 4 Bangkok Pattaya Part 2 Part 5 Kanchanaburi Rayong Part 3 Part 6 Hua Hin Trat ( Koh Chang ) BANGKOK Bangkok (Krungthep) which means “The City of Angels”, is known as the most vibrant city in South East Asia. It is ranked as No. 1 City of the World according to MasterCard’s latest Global Destination cities Survey. Bangkok welcomes more visitors than any other city in the world and it doesn’t take long to realise why this is a city of extremes with action on every corner: Marvel at the gleaming temples, catch a tuktuk along the bustling Chinatown or take a longtail boat through floating markets. Food is another Bangkok highlight with local dishes served at humble street stalls to haute cuisine at romantic rooftop restaurants. Luxury malls compete with a sea of boutiques and markets where you can treat yourself without over spending. Extravagant five-star hotels and surprisingly cheap but good hotels welcome you with the same famed Thai hospitality. And visit to Bangkok would not be complete without a glimpse of its famous nightlife – from cabarets to exotic nightlife districts, Bangkok never ceases to amaze. -

Songkran Splendoursplendour

Thailand Travel Talk Thailand Travel MARCH — APRIL APRIL 2013 SongkranSongkran SplendourSplendour When : 12-21 April 2013 Where : Nationwide SONGKRAN is a Thai traditional New Year Day which falls on April 13- Chiang Mai Songkran Festival: Chiang Mai City, Chiang Mai 15 every year. It is one of the most important festivals that is celebrated not Province only in Thailand but also in neighbouring countries such as Laos, Cambo- There are many activities during this famous event, for example, the dia and Myanmar. procession and bathing of Phra Buddhasihing, riding a Kang Chong (A Songkran is also called the Water Festival, a festival which is believed northern vehicle), carrying sand to the temple and cultural performances. to wash away all bad omens during this time. The tourists also enjoy the fun splashing of water around the moat of Chi- Traditionally, the activities on Songkran Day begin in the early morning ang Mai which is very famous and popular for both Thais and foreigners. when Thai Buddhists go to the temple to make merits by offering food to Hatyai Midnight Songkran Festival: Odeon Intersection, monks and listening to the Dhamma talks. In the afternoon, Thai Buddhists Sanehanuson Road, Niphat Uthit 3 Road, Hatyai District, sprinkle scented water on Buddha images. During this time, the younger Songkhla Province people ask blessings from the elders and pour scented water over their The activities during this event include the procession of Songkran at elder's hands. In return, the elders wish them good health, happiness and midnight, foam party, merit-making by offering food to the monks and prosperity. -

The Pattern of Elderly Health Tourism in Bangkok, Thailand

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 7, No. 2, February 2017 The Pattern of Elderly Health Tourism in Bangkok, Thailand Poonsup Setsri The government has set a development strategy for South Asia at the center of health (Medical Hub of Asia), which Abstract—The research study on the pattern of elderly consists of Medical Services Business Health and health health tourism in Bangkok. The objective is to study the products and herbal Thailand [4]. Medical Services, the core pattern of elderly health tourism in Bangkok. The comparison business is the key. The operator is a private hospital [5]. between the behavior of the elderly with a medical tourism for Currently, the operator of the 256 by a private hospital that the elderly. The researcher collected data using a questionnaire. The samples used in this research is. Elderly people living in has the potential to accommodate a foreigner more than 100, the Dusit area. Of 400 people found the majority were female and the evolution of key medical and promising growth area than male. Accounted for 18 percent Aged between 50-55 years, is to preventative medicine (Preventive Medicine. ), which mostly under graduate degree. And most seniors do not have focuses on prevention and health care prior to any disease. It underlying disease. The study Tourism activity patterns that fit has been increasingly popular in the United States. elderly were divided into 5 categories, including massage, Countries in Europe including Thailand, Alternative massage and herbal sauna. Practicing meditation and ascetic. Medicine. As a form of investment in associated potential.