Stadnicki Dissertation Second Draft March

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

SEM 62 Annual Meeting

SEM 62nd Annual Meeting Denver, Colorado October 26 – 29, 2017 Hosted by University of Denver University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado College SEM 2017 Annual Meeting Table of Contents Sponsors .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Committees, Board, Staff, and Council ................................................................................................................................................... 2 – 3 Welcome Messages ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Exhibitors and Advertisers ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 – 7 Charles Seeger Lecture...................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Schedule at a Glance. ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Music in the World of Islam a Socio-Cultural Study

Music in the World of Islam A Socio-cultural study Arnnon Shiloah C OlAR SPRESS © Arnnon Shiloah, 1995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise withoııt the prior permission of the pııb lisher. Published in Great Britain by Scolar Press GowerHouse Croft Road Aldershat Hants GUll 31-IR England British Library Cataloguing in Pııblication Data Shiloah, Arnnon Music in the world of Islam: a socio-cultural study I. Title 306.4840917671 ISBN O 85967 961 6 Typeset in Sabon by Raven Typesetters, Chester and printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford Thematic bibliography (references) Abbreviations AcM Acta Musicologica JAMS Journal of the American Musicological Society JbfMVV Jahrbuch für Musikalische Volks- und Völkerkunde JIFMC Journal of the International Fo lk Music Council JRAS Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society RE! Revue des Etudes Islamiques S!Mg Sammelbiinde der In temationale Musikgesellschaft TGUOS Transactions of the Glasgow University Oriental Society YIFMC Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council YFTM Yearbook for Traditional Music ZfMw Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft I. Bibliographical works (see also 76) 1. Waterman, R. A., W. Lichtenwanger, V. H. Hermann, 'Bibliography of Asiatic Musics', No tes, V, 1947-8,21, 178,354, 549; VI, 1948-9, 122,281,419, 570; VII, 1949-50,84,265,415, 613; VIII,1950-51, 100,322. 2. Saygun, A., 'Ethnomusicologie turque', AcM, 32, 1960,67-68. 3. Farmer, H. G., The Sources ofArabian Music, Leiden: Brill, 1965. 4. Arseven, V., Bibliography of Books and Essays on Turkish Folk Music, Istanbul, 1969 (in Turkish). -

I Silenti the Next Creation of Fabrizio Cassol and Tcha Limberger Directed by Lisaboa Houbrechts

I SILENTI THE NEXT CREATION OF FABRIZIO CASSOL AND TCHA LIMBERGER DIRECTED BY LISABOA HOUBRECHTS Notre Dame de la détérioration © The Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld, photo Erwin Blumenfeld vers 1930 THE GOAL For several years Fabrizio Cassol has been concentrating on this form, said to be innovative, between concert, opera, dance and theatre. It brings together several artistic necessities and commitments, with the starting point of previously composed music that follows its own narrative. His recent projects, such as Coup Fatal and Requiem pour L. with Alain Platel and Macbeth with Brett Bailey, are examples of this. “I Silenti proposes to be the poetical expression of those who are reduced to silence, the voiceless, those who grow old or have disappeared with time, the blank pages of non-written letters, blindness, emptiness and ruins that could be catalysers to other ends: those of comfort, recovery, regeneration and beauty.” THE MUSIC Monteverdi’s Madrigals, the first vocal music of our written tradition to express human emotions with its dramas, passions and joys. These Madrigals, composed between 1587 and 1638, are mainly grouped around three themes: love, separation and war. The music is rooted, for the first time, in the words and their meaning, using poems by Pétraque, Le Tasse or Marino. It is during the evolution of this form and the actual heart of these polyphonies that Monteverdi participated in the creation of the Opera as a new genre. Little by little the voices become individualized giving birth to “arias and recitatives”, like suspended songs prolonging the narrative of languorous grievances. -

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Had Murdered Krystle Marie Campbell, Lingzi Lu, Martin Richard, and Officer Sean Collier, He Was Here in This Courthouse

United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 16-6001 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. DZHOKHAR A. TSARNAEV, Defendant, Appellant. APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS [Hon. George A. O'Toole, Jr., U.S. District Judge] Before Torruella, Thompson, and Kayatta, Circuit Judges. Daniel Habib, with whom Deirdre D. von Dornum, David Patton, Mia Eisner-Grynberg, Anthony O'Rourke, Federal Defenders of New York, Inc., Clifford Gardner, Law Offices of Cliff Gardner, Gail K. Johnson, and Johnson & Klein, PLLC were on brief, for appellant. John Remington Graham on brief for James Feltzer, Ph.D., Mary Maxwell, Ph.D., LL.B., and Cesar Baruja, M.D., amici curiae. George H. Kendall, Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLP, Timothy P. O'Toole, and Miller & Chevalier on brief for Eight Distinguished Local Citizens, amici curiae. David A. Ruhnke, Ruhnke & Barrett, Megan Wall-Wolff, Wall- Wolff LLC, Michael J. Iacopino, Brennan Lenehan Iacopino & Hickey, Benjamin Silverman, and Law Office of Benjamin Silverman PLLC on brief for National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, amicus curiae. William A. Glaser, Attorney, Appellate Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice, with whom Andrew E. Lelling, United States Attorney, Nadine Pellegrini, Assistant United States Attorney, John C. Demers, Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, John F. Palmer, Attorney, National Security Division, Brian A. Benczkowski, Assistant Attorney General, and Matthew S. Miner, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, were on brief, for appellee. July 31, 2020 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. OVERVIEW Together with his older brother Tamerlan, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev detonated two homemade bombs at the 2013 Boston Marathon, thus committing one of the worst domestic terrorist attacks since the 9/11 atrocities.1 Radical jihadists bent on killing Americans, the duo caused battlefield-like carnage. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER Good Luck

Good Luck WHS Football Team THE WESTFIELD LEADER In Pljd. Tomorrow THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY Published .ontl Class I'uBtiiee Paid EIGHTY-FIRST YEAR—No. 16 Every Tlwraday WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 25, 1970 ut West field, N. J. 32 Papes—10 Centt Service Aids Cacciola PL Town to Begin Work Royai Natai McGroarty, Cohen, Mayer On Southside Park Day for Ham ^ • ,.• ^ Project It was a happy birthday indeed Improvements to the North Scotch assessed against the property own- last Wednesday for Matltlhew BeJl Westfield residents of all religious Plains Ave. park recreation area ers, would include granite curbing, communions will join together in a of 14 Manchester Dr.—and it even Decline New B of E Terms are slated in an ordinance expected macadam paving and a sanitary Community Thanksgiving Service at included royal greetings from King Joseph A. McGroarty, Dr. Solomon to be introduced at last night's meet- sewer lateral in the section of Nor- Hussein of Jordan. the Presbyterian Church of Westfield ing of the Town Council. The council mandy Dr., a new street which runs J. Cohen and Charles R. Mayer, the at 8 p.m. tonight. Rabbi Charles "Many happy returns of the day," three Board of Education members was in session at the time the Leader {ram Rs-hway Ave. Owners would the cablegram read: "AH my best Kroloff of Temple Emami-El will be went to press. be required to make Hie necessary -whose terms expire this year, have the featured speaker, with his sub- wishes and regards." notified the Joint Civic Committee The $20,000 improvements would connections from their homes with ject, "Between the Poles." Also par- the sewer, water and gas mains. -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

Integrating Việt Nam Into World History Surveys

Southeast Asia in the Humanities and Social Science Curricula Integrating Việt Nam into World History Surveys By Mauricio Borrero and Tuan A. To t is not an exaggeration to say that the Việt Nam War of the 1960–70s emphasize to help students navigate the long span of world history surveys. remains the major, and sometimes only, point of entry of Việt Nam Another reason why world history teachers are often inclined to teach into the American imagination. Tis is true for popular culture in Việt Nam solely in the context of war is the abundance of teaching aids general and the classroom in particular. Although the Việt Nam War centered on the Việt Nam War. There is a large body of films and docu- ended almost forty years ago, American high school and college stu- mentaries about the war. Many of these films feature popular American dents continue to learn about Việt Nam mostly as a war and not as a coun- actors such as Sylvester Stallone, Tom Berenger, and Tom Cruise. There Itry. Whatever coverage of Việt Nam found in history textbooks is primar- are also a large number of games and songs about the war, as well as sub- ily devoted to the war. Beyond the classroom, most materials about Việt stantial news coverage of veterans and the Việt Nam War whenever the Nam available to students and the general public, such as news, literature, United States engages militarily in any part of the world. American lit- games, and movies, are also related to the war. Learning about Việt Nam as erature, too, has a large selection of memoirs, diaries, history books, and a war keeps students from a holistic understanding of a thriving country of novels about the war. -

Den John Esslemont (1874 - 1925) a Wéi D‘Muecht Vum Bond Hie Belieft Huet

Den John Esslemont (1874 - 1925) a wéi d‘Muecht vum Bond hie belieft huet Zënter 1998 hunn ech d’Chance, un de Formatioune vum Institut de Formation, Bahá’í Lëtzebuerg, deelzehuelen, sief et als Participant oder als Tuteur. Elo zielen ech iech gär vun engem Léiermoment am Ruhi Buch 8, aus menger Perspektiv, do wou ech haut sinn. An engem Grupp vu 4-5 Leit a mat eisem Tutor, hu mir Sonndes moies tëscht 9:30 an 12:15 d‘Buch 8, De Bond vu Bahá’u’lláh, déi 1. Unitéit: Den Zentrum vum Bond a säin Testament, zesumme gelies, Froen zum Text gestallt an duerch eis Ergänzunge probéiert, den Inhalt besser ze verstoen an ze kucken, wéi mir dat Geléiert an eisem Alldag praktesch ëmsetze kënnen. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá ass de Mëttelpunkt vum Bond vu Baháʼu'lláh, an Hie seet, dass dëse Bond allmächteg ass, eng „universal Wo“, e „Magnéit vu Gottes Gnod“, e Bond dee „sengesgläichen, an den hellege Sendunge vun der Vergaangenheet, sicht“. 1 Am Abschnitt 20 gesi mer kuerz, wéi de Glawe sech am Weste verbreet huet. Verantwortlech dofir war virun allem ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Et gi vill Geschichten, déi mat dëser aussergewéinlecher Period vun der Geschicht vum Glawe verbonne sinn, a Séilen, déi den Appell vu Bahá’u’lláh héieren hunn a sech entschloss hunn, sech fir d’Saach anzesetzen. Mir sollen hei eis eege Recherche maachen iwwer d’Liewe vun engem vun den éischte Gleewegen aus dem Westen an eng kleng Presentatioun fir de Grupp virbereeden. Mir solle versichen ze weisen, wéi d’Muecht vum Bond jiddeere vun hinne belieft huet. -

Dossier De Presse

14 JUIN -> 6 JUILLET 2019 DOSSIER DE PRESSE DOSSIER DE PRESSE Photographie : © Léa Magnien & Quentin Chantrel - Collectif Lova Lova / Graphisme : Floriane Ollier CONTACT PATRICIA LOPEZ DOMINIQUE BEROLATTI 06 11 36 16 03 06 14 09 19 00 PRESSE [email protected] [email protected] p. 6 CION : LE REQUIEM DU BOLÉRO DE RAVEL - Gregory Maqoma 13, 14, 15, 16 JUIN - THÉÂTRE LA CRIÉE p. 8 LE SACRE 15, 16 JUIN - PARC BORÉLY p. 10 SOUS INFLUENCE - Éric Minh Cuong Castaing 15 JUIN - [MAC] MUSÉE D’ART CONTEMPORAIN p. 12 LABORATOIRE POISON 2 - Adeline Rosenstein 16 JUIN - THÉÂTRE LA CRIÉE week-end d’ouverture week-end p. 14 NOT ANOTHER DIVA... - Hlengiwe Lushaba et Faustin Linyekula 16, 17 JUIN -THÉÂTRE DE LA SUCRIÈRE p. 18 47 SOUL 19 JUIN -THÉÂTRE DE LA SUCRIÈRE p. 20 TOUT PEUT CHANGER - Avi Lewis et Naomi Klein 20 JUIN -ALHAMBRA p. 22 MOUN FOU - Rara Woulib 22 JUIN semaine 1 p. 24 L’AUTRE - Dorothée Munyaneza 22, 23 JUIN p. 26 LA CHANSON DE ROLAND - Wael Shawky 22, 23 JUIN - MUCEM > PLACE D’ARMES p. 29 Un Lundi déplacé 24 JUIN - ENTRE LE PLAN D’AOU ET LA GARE FRANCHE p. 30 KHOUYOUL - kabinet k et l’Art rue 24, 25, 26 JUIN - FRICHE LA BELLE DE MAI > GRAND PLATEAU p. 34 LE MOINDRE GESTE - Selma et Sofiane Ouissi 27, 28, 29, 30 JUIN - KLAP, MAISON POUR LA DANSE p. 38 INVITED - Seppe Baeyens | Ultima Vez 28, 29 JUIN - LA GARE FRANCHE semaine 2 p. 42 LUMINESCENCE - Amir ElSaffar 28, 29 JUIN - VIEILLE CHARITÉ p. -

Key: Carlos Hernandez Entries = Red Carlos Deluna Entries = Blue Entries That Apply to Both of Them = Purple Wanda Lopez Entries

Key: Carlos Hernandez entries = Red Carlos DeLuna entries = Blue Entries that apply to both of them = Purple Wanda Lopez entries = Green Information about day of crime (that could apply to both) = Black [I put date of info entry in brackets where previous key indicated it.] CH background: 1995 Address on Memorial Medical Center records: 1817 Shely, CC, TX 78404 1994 Address, drivers license, DPS and as of 9/14/94: 1817 Shely, CC, TX 78404; as of 4/28/94, at 1100 Leopard #47 (hard to read number) 1993 Address (11/26/93): 822 Hancock #1 1991 Address, drivers license/DPS: 822 Hancock #1, CC, TX 78404 th 1989 Address (4/15/89): 826 Hancock and 714 7 St. 1987 Address (1/21/87): 1010 Buford and 1201 South Alameda #2; as of 5/5/87 and 7/16/ 87 at 826 Hancock # C. 1986 Address: (3/26/86): 1010 Buford, CC; as of 7-24-86, at 1201 South Alameda #2 1985 Address: (5/9/85 and other): 1010 Buford, #C, CC 11/1983 address: 1008 Buford, CC; also (Sheriffs Dep’t Records) 1201 South Alameda [Added 10/13/04, 11/2/04] 1983 Address (4/8/83, and 11/83, with Rosa Anzaldua): 107 Sam Rankin, CC 1982 Address (10-10-82, with Rosa Anzaldua): 107 Sam Rankin, CC 1981 Address (10/26/81): 217 S. Carrizo 1980 (1/10/80; 2/16/80; 5/4/80; 5/6/80) Address: 217 Carrizo St.; 217 S. Carrizo, CC, TX 78401, 883-4127 (from DPS drivers license; also added Added 10/13/04, 11/2/04] 1979 Address (2/12/79): 217 Carrizo St CC 1978 (7/29, 8/19 and 10/19) Address: 217 South Carrizo St. -

Read the Introduction

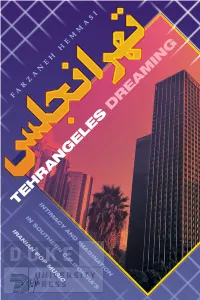

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try.