Ownership of the Means of Production∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

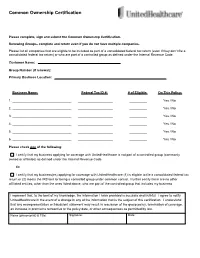

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit To cite this version: Fabien Tarrit. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership. Buletinul Stiintific Academia de Studii Economice di Bucuresti, Editura A.S.E, 2008, 9 (1), pp.347-355. hal-02021060 HAL Id: hal-02021060 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02021060 Submitted on 15 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership TARRIT Fabien Lecturer in Economics OMI-LAME Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne France Abstract: This article intends to demonstrate that the concept of self-ownership does not necessarily imply a justification of inequalities of condition and a vindication of capitalism, which is traditionally the case. We present the reasons of such an association, and then we specify that the concept of self-ownership as a tool in political philosophy can be used for condemning the capitalist exploitation. Keywords: Self-ownership, libertarianism, capitalism, exploitation JEL : A13, B49, B51 2 The issue of individual freedom as a stake went through the philosophical debate since the Greek antiquity. We deal with that issue through the concept of self-ownership. -

Common Ownership Community “COC”

So, are you a good neighbor? Do you know your association’s Board of Directors? Do you … ? Are you aware of when and where your association • Pay your assessments on time? meets? Have you reviewed your association’s • Abide by the rules, regulations and bylaws? bylaws? • Attend Board of Directors meetings? • Vote in elections and on critical matters? How to be a Consider getting involved. Get engaged and be aware! For additional information on Common GOOD NEIGHBOR in a Ownership Communities, please contact the • Browse your Association’s newsletter and email following: blasts, so that you have an idea of what’s going on and, so that you’ll be able to participate Office of Community Relations Common if there’s something you strongly agree or Ownership Communities disagree with. Phone: 301-952-4729 http://www.princegeorgescountymd.gov/921/ • Attend Association meetings. This will help Common-Ownership-Communities you find out what’s going on in your community and will help you become informed. You’ll FHA Resource Center have a greater influence over what happens https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/ in your building or neighborhood and it’s an sfh/fharesourcectr opportunity to meet your neighbors. Office of the Attorney General Consumer At the end of the day, there is a difference between Protection Division living in a community and being a part of that Phone: 877-261-8807 particular community. While being part of an http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/ Common Association can be a bit of extra work, it’s worth CPD%20Documents/Tips-Publications/ putting some effort into being a good member. -

Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 10:10:51PM Via Free Access

JOBNAME: EE3 Hodgson PAGE: 2 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Thu Jun 27 12:00:07 2019 1. What does socialism mean? Under capitalism, man exploits his fellow man. Under socialism it is precisely the opposite. Eastern European joke from the Communist era1 The word socialism is modern, but the impulse behind it is ancient. The idea of holding property in common goes back to Ancient Greece and is found in the Bible.2 It has been harboured by some religions and it has been the call of radicals for centuries. In his 1516 book Utopia, Sir Thomas More imagined a system where everything was held in common ownership and internal trade was abolished. Unlike most other proposals for common ownership before the 1840s, More’s Utopia envisioned cities of between 60 000 and 100 000 adults. It is the first known proposal for what I call big socialism. Before the rise of Marxism, the predominant vision of common ownership was small-scale, rural and agricultural. It was often motivated by religious doctrine. In Germany in the 1520s the radical Protestant Thomas Müntzer proposed a Christian communism. From 1649 to 1650, during the English Civil War, the Diggers set up religious communes whose members worked together on the soil and shared its produce. There are other examples of socialism before the word was coined.3 This chapter is about the origins, meaning and evolution of the words socialism and communism. They are virtual synonyms, both largely referring to common ownership of the means of production and to the abolition of private property. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A LeftLeft----LibertarianLibertarian Theory of Rights Arabella Millett Fisher PhD University of Edinburgh 2011 Contents Abstract....................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................v Declaration.................................................................................................................. vi Introduction..................................................................................................................1 Part I: A Libertarian Theory of Justice...................................................................11 -

Keywords—Marxism 101 Session 1 Bourgeoisie

Keywords—Marxism 101 Session 1 Bourgeoisie: the class of modern capitalists, owners of the means of social production and employers of wage labour. Capital: an asset (including money) owned by an individual as wealth used to realize a fnancial proft, and to create additional wealth. Capital exists within the process of economic exchange and grows out of the process of circulation. Capital is the basis of the economic system of capitalism. Capitalism: a mode of production in which capital in its various forms is the principal means of production. Capital can take the form of money or credit for the purchase of labour power and materials of production; of physical machinery; or of stocks of fnished goods or work in progress. Whatever the form, it is the private ownership of capital in the hands of the class of capitalists to the exclusion of the mass of the population. Class: social stratifcation defned by a person's relationship to the means of production. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bf/Pyramid_of_Capitalist_System.png Class struggle: an antagonism that exists within a society, catalyzed by competing socioeconomic interests and central to revolutionary change. Communism: 1) a political movement of the working class in capitalist society, committed to the abolition of capitalism 2) a form of society which the working class, through its struggle, would bring into existence through abolition of classes and of the capitalist division of labor. Dictatorship of the Proletariat: the idea that the proletariat (the working class) has control over political power in the process of changing the ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership as part of a socialist transition to communism. -

Mode of Production and Mode of Exploitation: the Mechanical and the Dialectical'

DjalectiCalAflthropologY 1(1975) 7 — 2 3 © Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam — Printed in The Netherlands MODE OF PRODUCTION AND MODE OF EXPLOITATION: THE MECHANICAL AND THE DIALECTICAL' Eugene E. Ruyle In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage of development of their material produc- tive forces. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstruc- ture and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that deter- mines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.2 The specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labor is pumped out of the direct producers, determines the relation of rulers and ruled, as it grows immediately out of production itself and in turn reacts upon it as a determining agent. .. It is always the direct relation of the owners of the means of production to the direct producers which reveals the innermost secret, the hidden foundation of the entire social structure.3 In the first of these two passages, Marx in crypto-Marxist bourgeois social science, and appears to be arguing for the sort of techno- then by exploring the possibilities of supple- economic determinism which has become menting the "mode of production" approach increasingly fashionable in bourgeois social with a "mode of exploitation" analysis. -

Production Modes, Marx's Method and the Feasible Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal November 2016 edition vol.12, No.31 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Production Modes, Marx’s Method and the Feasible Revolution Bruno Jossa retired full professor of political economy, University ”Federico II”, Naples doi: 10.19044/esj.2016.v12n31p20 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n31p20 Abstract In Marx, the production mode is defined as a social organisation mode which is typified by one dominant production model which confers significance on the system at large. The prominence of production modes in his overall approach provides clues to the identification of the correct scientific method of Marxism and, probably, of Marx himself. The main aim of this paper is to define this method and to discuss a type of socialist revolution which appears feasible in this day and age. Keywords: Marx’s method, producer cooperatives, production modes, socialism Introduction It is not from scientific advancements – Gramsci argued – that we are to expect solutions to the issues on the traditional agenda of philosophical research. Fresh inputs for philosophical speculation have rather come from notions such as ‘social production relations’ and ‘modes of production’, which are therefore Marx's paramount contributions to science.1 In a well-known 1935 essay weighing the merits and 1 For quite a long time, Marxists used to look upon the value theory as Marx’s most important contribution to science. Only when the newly-published second and third books of Capital revealed that Marx had tried to reconcile his value theory with the doctrine of prices as determined by the interplay of demand and supply did they gain a correct appreciation of the importance of the materialist conception of history. -

The Political and Social Thought of Lewis Corey

70-13,988 BROWN, David Evan, 19 33- THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL THOUGHT OF LEWIS COREY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Political Science, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL THOUGHT OF LEWIS COREY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David Evan Brown, B.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser Department of Political Science PREFACE On December 2 3 , 1952, Lewis Corey was served with a warrant for his arrest by officers of the U, S, Department of Justice. He was, so the warrant read, subject to deportation under the "Act of October 16 , 1 9 1 8 , as amended, for the reason that you have been prior to entry a member of the following class: an alien who is a member of an organi zation which was the direct predecessor of the Communist Party of the United States, to wit The Communist Party of America."^ A hearing, originally arranged for April 7» 1953» but delayed until July 27 because of Corey's poor health, was held; but a ruling was not handed down at that time. The Special Inquiry Officer in charge of the case adjourned the hearing pending the receipt of a full report of Corey's activities o during the previous ten years. [The testimony during the hearing had focused primarily on Corey's early writings and political activities.] The hearing was not reconvened, and the question of the defendant's guilt or innocence, as charged, was never formally settled.