Report of the Government on the Application of Language Legislation 2013 ISBN 978-952-259-326-9 (Pb.) ISBN 978-952-259-327-6 (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Structure 2009

Population 2010 Population Structure 2009 Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population lowest in over 100 years According to Statistics Finland’s statistics on the population structure there were 888,323 persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population at the end of 2009. The number is the lowest since 1895. The size of the population under the age of 15 has been decreasing continuously since 1994. At the end of 1977, there were still one million persons aged under 15 in the Finnish population. The size of the population under the age of 15 was at its largest in 1959 when it was 1.35 million. Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population in 1875–2009 On 31 December 2009, the total population of Finland was 5,351,427 in which 2,625,067 were men and 2,726,360 women. In the course of 2009, Finland’s population grew by 25,113 persons. For the third successive year migration gain from abroad contributed more to the increase of population than natural growth. During 2009, the number of persons aged 65 and over in the population increased by good 18,000 and totalled 910,441 at the end of 2009. The largest age cohort in Finland’s population was persons born in 1948. At the end of 2009, they numbered 82,738. Persons over 100 years of age numbered 566, of whom 82 were men and 484 women. Demographic dependency ratio highest in Etelä-Savo and lowest in Uusimaa The demographic dependency ratio, that is the number of under 15 and over 65-year-olds per 100 working age persons was 50.6 at the end of 2009. -

Labour Market Areas Final Technical Report of the Finnish Project September 2017

Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 1(37) Labour Market Areas Final Technical report of the Finnish project September 2017 Data collection for sub-national statistics (Labour Market Areas) Grant Agreement No. 08141.2015.001-2015.499 Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Postal address: 3rd floor, FI-00022 Statistics Finland E-mail: [email protected] Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 2(37) Contents: 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work 1.2 Finland’s national travel-to-work areas 1.3 Tasks of the project 2. Results of the Finnish project 2.1 Improving IT tools to facilitate the implementation of the method (Task 2) 2.2 The finished SAS IML module (Task 2) 2.3 Define Finland’s LMAs based on the EU method (Task 4) 3. Assessing the feasibility of implementation of the EU method 3.1 Feasibility of implementation of the EU method (Task 3) 3.2 Assessing the feasibility of the adaptation of the current method of Finland’s national travel-to-work areas to the proposed method (Task 3) 4. The use and the future of the LMAs Appendix 1. Visualization of the test results (November 2016) Appendix 2. The lists of the LAU2s (test 12) (November 2016) Appendix 3. The finished SAS IML module LMAwSAS.1409 (September 2017) 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work In the background of the action was the need for comparable functional areas in EU-wide territorial policy analyses. The NUTS cross-national regions cover the whole EU territory, but they are usually regional administrative areas, which are the re- sult of historical circumstances. -

Helsinki-Uusimaa Region Competence and Creativity

HELSINKI-UUSIMAA REGION COMPETENCE AND CREATIVITY. SECURITY AND URBAN RENEWAL. WELCOME TO THE MODERN METROPOLIS BY THE SEA. HELSINKI-UUSIMAA REGIONAL COUNCIL HELSINKI-UUSIMAA REGION AT THE HEART OF NORTHERN EUROPE • CAPITAL REGION of Finland • 26 MUNICIPALITIES, the largest demographic and consumption centre in Finland • EXCELLENT environmental conditions - 300 km of coastline - two national parks • QUALIFIED HUMAN CAPITAL and scientific resources • INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT • four large INTERNATIONAL PORTS • concentration of CENTRAL FUNCTIONS: economy, administration, leisure, culture • privileged GEO-STRATEGIC LOCATION Helsinki-Uusimaa Region AT THE HEART OF POPULATION • 1,6 MILLION inhabitants • 30 % of the population of Finland • POPULATION GROWTH 18,000 inhabitants in 2016 • OFFICIAL LANGUAGES: Finnish mother tongue 80.5 %, Swedish mother tongue 8.2 % • other WIDELY SPOKEN LANGUAGES: Russian, Estonian, Somali, English, Arabic, Chinese • share of total FINNISH LABOUR FORCE: 32 % • 110,000 business establishments • share of Finland’s GDP: 38.2 % • DISTRIBUTION OF LABOUR: services 82.5 %, processing 15.9 %, primary production 0.6 % FINLAND • republic with 5,5 MILLION inhabitants • member of the EUROPEAN UNION • 1,8 MILLION SAUNAS, 500 of them traditional smoke saunas • 188 000 LAKES (10 % of the total area) • 180 000 ISLANDS • 475 000 SUMMER HOUSES • 203 000 REINDEER • 39 NATIONAL PARKS HELSINKI-UUSIMAA SECURITY AND URBAN RENEWAL. WELCOME TO THE MODERN METROPOLIS BY THE SEA. ISBN 978-952-448-370-4 (publication) ISBN 978-952-448-369-8 (pdf) -

Selvitys Käytöstä Poistettujen Kaatopaikkojen Pinta- Ja Pohja- Vesitarkkailusta Uudellamaalla Maria Arola

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Library of Finland DSpace Services Selvitys käytöstä poistettujen kaatopaikkojen pinta- ja pohja- vesitarkkailusta Uudellamaalla Maria Arola Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskuksen julkaisuja 6/2011 Selvitys käytöstä poistettujen kaatopaikkojen pinta- ja pohja- vesitarkkailusta Uudellamaalla Maria Arola 6/2011 Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskuksen julkaisuja Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne ja ympäristökeskuksen julkaisuja 6 | 2011 1 ISBN 978-952-257-313-1 (PDF) ISSN-L 1798-8101 ISSN 1798-8071 verkkojulkaisu Julkaisu on saatavana myös verkkojulkaisuna: http://www.ely-keskus.fi/uusimaa/julkaisut http://www.ely-centralen.fi/nyland/publikationer Valokuvat: Maria Arola Kartta: Maria Arola © Maanmittauslaitos lupa nro 7 MML/2011 2 Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne ja ympäristökeskuksen julkaisuja 6|2011 Sisällys 1 Johdanto 5 1.1 Jätteiden loppusijoituksen historia ............................................................... 5 1.2 Käytöstä poistettujen kaatopaikkojen tila ..................................................... 5 2 Kaatopaikkoja ohjaavan lainsäädännön kehittyminen 8 2.1 Vesilaki (264/1961) ja -asetus (282/1962) ....................................................... 8 2.2 Asetus vesien suojelua koskevista ennakkotoimenpiteistä (283/1962) ..... 8 2.3 Terveydenhoitolaki (469/1965) ja -asetus (55/1967) ...................................... 8 2.4 Jätehuoltolaki (673/1978) ja -asetus (307/1979) ........................................... -

Julkaisusarjan Nimi

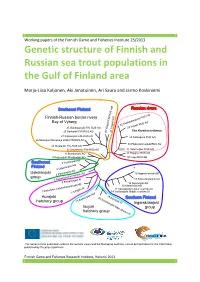

Working papers of the Finnish Game and Fisheries Institute 25/2013 Genetic structure of Finnish and Russian sea trout populations in the Gulf of Finland area Marja-Liisa Koljonen, Aki Janatuinen, Ari Saura and Jarmo Koskiniemi M A S U R O - S A O U Finnish-Russian border rivers N R I o A r u F i p an i l k ka Bay of Vyborg k k O o o A j u o K S j RU o 32 ki a r jo l i Ino i 29 25 Rakkolanjoki FIN-RUS AO V V 1 4 The Karelian Isthmus 23 Santajoki FIN-RUS AO 2 2 27 Kilpeenjoki FIN-RUS AO 28 Notkopuro RUS AO 26 Mustajoki Kananoja 2006 FIN-RUS AO 30 Pikkuvammeljoki RUS AO 26 Mustajoki FIN-RUS AO 22 Urpalanjoki FIN-RUS AO 31 Vammeljoki RUS AO 11 Siuntionjoki AO 33 Rajajoki RUS AO 9 Karjaanjoki Mustionjoki AO 34 Luga RUS AO O njoki A 3 Purila i AO lanjok Uske 5 oki AO Uskelanjoki mionj O 10 Ingarskilanjoki AO 2 Pai oki A rniönj group oki Pe skonj 18 Koskenkylanjoki AI 7 Ki joki AI skarsin 8 Fi 15 Sipoonjoki AO M koski A 12 Mankinjoki AO rtanon Latoka AI 14 Vantaanjoki Lower reaches AI njoki joki Kisko ura 7 1 A 14 Vantaanjoki Middle reaches AI AM oki 1 Aurajoki onj 2 9 K po 0 S ym Es u ijo hatchery group 13 mm ki A an I Ingarskilanjoki jok i M Isojoki ai group n s tre hatchery group am AI The content of the publication reflects the authors views and the Managing Authority cannot be held liable for the information published by the project partners. -

We-House Kerava and Puluboi

We-house at Kerava – Supporting the wellbeing of families. Laurea University of Applied Sciences. We-house Kerava We-house Kerava is a low-threshold community house that is open to all citizens of Kerava. The facilitator of the we-house is The Mannerheim League for Child Welfare (MLL), Uudenmaa District, and for the first two years we-house is funded by the we-foundation, which aims to reduce social inequality and the exclusion of children, youth and families in Finland. During this time, we- house hopes to convince the city of Kerava to grant them permanent funding. The main aim of we-house Kerava (me-talo in Finnish) is to increase and promote the wellbeing of families and to provide them with support via participation, discussions with peers, and volunteering. We-house is open to all residents of Kerava and its neighboring areas regardless of age, gender or current social status. We-house offers a place for participation, inspiration and excitement; it brings joy to everyday life and enhances opportunities to find employment. All the activities and functions that arise from the wishes and needs of local residents are planned and carried out in conjunction with local service providers, organizations and companies. We-house provides open activities, decreases loneliness and enables different forms of support all under one roof. We-house also strengthens cooperation between the city of Kerava, organizations and parishes, as well as increasing volunteer activities in the area. Cooperation between we-house and Laurea UAS The bachelor’s degree in Social Services provides social services studies that incorporate the skills required to help and guide clients at different stages of life, as well as comprehensive skills the management of social services, service systems and legislation. -

Local Government Employment Pilots – Uusimaa TE Office Questions and Answers

Local government employment pilots – Uusimaa TE office Questions and answers 1. What is the local government employment pilot? The local government employment pilots are a project lasting more than two years in which some of the legally mandated employment services of TE offices are to be arranged by municipalities. Taking part in the project are 125 municipalities and 26 pilot areas formed by them. Participants in the Uusimaa region are Helsinki, Espoo, Vantaa, Kerava, Porvoo, Raasepori and Hanko. The regional pilots begin on 1 March 2021 and they end on 30 June 2023. 2. Why are the local government pilots being launched? In accordance with the Government programme, the role of municipalities in organising employment services is being strengthened. The purpose of the pilots is to improve access to the labour market, especially for those who have been unemployed for longer and those who are in a weaker position on the labour market. In addition, services are to be developed in the pilot that support the employment of a jobseeker, and service models in which the customer's situation and need for service are evaluated at the individual level. 3. What does this mean in practice? After the launch of a local government pilot some of the jobseeker customers will become customers of the municipalities, and some will remain with the TE office. When a customer is transferred to the local government pilot, his or her services will be primarily provided by his or her municipality of residence. The TE office will retain some tasks involving the customers that move to the local government pilots, such as statements on unemployment security and interviews and selections for vocational labour market training. -

Cultural Analysis an Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture

CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 18.1 Comparison as social and comparative Practice Guest Editor: Stefan Groth Cover image: Crachoir as a material artefact of comparisons. Coronette—Modern Crachoir Design: A crachoir is used in wine tastings to spit out wine, thus being able to compare a range of different wines while staying relatively sober. © Julia Jacot / EESAB Rennes CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Comparison as Social and Cultural Practice Special Issue Vol. 18.1 Guest Editor Stefan Groth © 2020 by The University of California Editorial Board Pertti J. Anttonen, University of Eastern Finland, Finland Hande Birkalan, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Charles Briggs, University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Anthony Bak Buccitelli, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, U.S.A. Oscar Chamosa, University of Georgia, U.S.A. Chao Gejin, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, University of Iceland, Reykjavik Jawaharlal Handoo, Central Institute of Indian Languages, India Galit Hasan-Rokem, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø, Norway Fabio Mugnaini, University of Siena, Italy Sadhana Naithani, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Peter Shand, University of Auckland, New Zealand Francisco Vaz da Silva, University of Lisbon, Portugal Maiken Umbach, University of Nottingham, England Ülo Valk, University of Tartu, Estonia Fionnuala Carson Williams, Northern Ireland Environment Agency -

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Talviaik Ata Ulut

INKOO – KIRKKONUMMI TH – HELSINKI 018 HELSINKI – KARJAA – TAMMISAARI 018 HELSINKI – KARJAA – FISKARI INGÅ – KYRKSLÄTT VGS – HELSINGFORS 018 HELSINGFORS – KARIS – EKENÄS 018 HELSINGFORS – KARIS – FISKARS Merkkien selitykset – Teckenförklaring: – VINTERTIDTABELLER TALVIAIKATAULUT 018 PIKA 018 018 018 018 018 V M–P M–P M–P M–P Laituri H:ki Laituri H:ki 27 16 16 27 16 26 16 16 27 + Kouluvuoden aikana – Under skolåret Ingå/Inkoo 7,15 ~7,55TH 9,10 15,05 Plattform H:fors M–P M–P M–P Plattform H:fors M–P M–P M–P M–P M–P M–P Helsinki/Helsingfors 9,25 13,25 16,10 Vain koulujen kesäloman aikana Helsinki/Helsingfors 9,25 13,25 14.15 16.10 17,00 18.45 ++ Kyrkslätt VGS/Kirkkonummi TH 7,45 x 9,35 15,30 Lauttasaari/Drumsö - x x Under skolans sommarlov K:nummi/Kyrkslätt th - 13,55 - 16.45 17,35 - Jorvas TH x x x x Jorvas th - x x +++ 1.5–30.9 K:nummi/Kyrkslätt th - 13,55 16,45 Inkoo/Ingå - 14,25 - 17.15 18,05 - Iso Omena x x x x Maanantaista perjantaihin Inkoo kk/Ingå kby - 14,25 17,15 Lohja/Lojo 15.30 - 20.05 M–P Lauttasaari/Drumsö x - x x Karjaa las/Karis busst 11,10 14,50 17,40 Från måndag till fredag Puh./Tfn Karjaa/Karis 11,10 14,40 16.30 17.40 18,30 20.50 E-mail Helsingfors/Helsinki Kamppi 8,20 8,50 10,05 16,00 Karjaa ras/Karis jv.st. I 17,45 Jatkaa tarvittaessa T Fax Tammisaari/Ekenäs 11,35 15,10 18,10 Pohja/Pojo 11,25 15,25 16.45 18,45 21.05 Fortsätter vid behov 2.1.2018 Alkaen / Fr.o.m. -

Nylands Svenska Lantbruksproducentförbund

Nylands svenska producentförbund NSP r.f. Publikation nr 93 ÅRSBERÄTTELSE 2017 SLC Nyland 2 DET NITTIOTREDJE VERKSAMHETSÅRET Förbundets medlemmar Antalet lokalavdelningar som var anslutna till förbundet minskade vid ingången av året från 19 till 17, då Karis och Snappertuna lokalavdelningar samt Pojo landsbygdsförening gick samman till en lokalavdelning, SLC Raseborg. Det betydde samtidigt att antalet medlemsföreningar i form av landsbygdsföreningar minskade från tre till två. Lokalavdelningarna hade vid slutet av år 2017 sammanlagt 1.383 lantbruks- och trädgårdslägenheter som medlemmar (aktiva). Dessa minskade med 1,1 procent från föregående år. Förbundet hade 316 stödande medlemmar (+ 0,3 %). Personmedlemmarnas antal uppgick till 3.149 (- 2,1 %). Medlemsgårdarnas sammanlagda areal utgjorde 59.045 ha åker (- 2,5 %) och 74.488 ha skog (- 0,4 %). Medlemsgårdarnas medelareal uppgick till 42,7 ha åker (+ 0,4 ha jmf. med 2016) och 53,9 ha skog (+ 0,5 ha). 307 lägenheter hade enbart skog. Om man beaktar endast aktiva gårdar som hade åkermark i besittning blir åkerns medelareal ca 12,2 hektar större, d.v.s. 54,9 ha. Det här motsvarar rätt väl medelarealen för lantbruken i Nyland. Stödande företagsmedlemmar Följande företag och organisationer var stödande medlemmar 2017: Andelsmejeriet Länsi Maito Andelsmejeriet Tuottajain Maito Arla Oy LSO Andelslag Svenska Småbruk och Egna Hem Södra skogsreviret Folksam skadeförsäkring FÖRBUNDETS ORGANISATION 2017 Förbundsstyrelsen Förbundsordförande och ordförande i styrelsen sedan 2004, Thomas Blomqvist. Adress: Bonäsvägen 100 C, 10520 TENALA, tel. 050 5121776, e-post: [email protected]. I viceordförande Thomas Antas, ledamot i styrelsen sedan 2002, viceordförande sedan 2015. Adress: Hindersbyvägen 622, 07850 HINDERSBY, tel. 050 3079919, e-post: [email protected]. -

Pohja Parish Village

SERVICES POHJA PARISH VILLAGE FOOD AND BEVERAGES Pohja parish village is situated in the city of Raseborg, at the bottom of Pohjanpitäjä Bay, along the historical King’s Highway. 1. Backers Café and Bakery In the parish village of Pohja and its surroundings there is a lot to see and experience. Borgbyntie 2, 10440 Bollsta. Phone +358 19 246 1656, +358 19 241 1674, A medieval church built of stone, Kasberget’s grave from the Bronze Age, the first www.backers.fi railway tunnel in Finland constructed for passenger traffic, the agricultural and home- 2. DeliTukku and Restaurant Glöden stead museum of Gillesgården, sports center Kisakeskus, two full-length golf courses, Pohjantie 8, 10420 Pohjankuru. Phone +358 20 763 9121, www.delitukku.fi Påminne sports center, riding centers and much more. In the vicinity are the foundries 3. Restaurant Åminnegård from the 17th century in Fiskars (3 miles away), Billnäs (5 miles) and Antskog (8 miles). Åminnen kartanontie 4, 10410 Åminnefors. Phone +358 19 276 6890, The Pohjanpitäjä Bay is a 9-mile-long fjord-like inlet, which splits the area of the city of www.nordcenter.com Raseborg from the parish village of Pohja to the Gulf of Finland. It is a brackish water 4. Ruukkigolf area and has one of the richest abundance of species in Finland. In the Bay there are Hiekkamäentie 100, 10420 Pohjankuru. Phone +358 19 245 4485, www.ruukkigolf.fi both brackish water and freshwater fishes. 5. Sports Center Kisakeskus The mild climate and the rather unbuilt shores result in a versatile and rich flora and Kullaanniemi 220, 10420 Pohjankuru.