LATE MEDIEVAL NUPTIAL RITES Paride Grassi and the Royal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware of False Shepherds, Warhs Hem. Cardinal

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Principals in Pallium Ceremony i * BEWARE OF FALSE SHEPHERDS, % WARHS HEM. CARDINAL STRITCH Contonto Copjrrighted by the Catholic Preas Society, Inc. 1946— Pemiosion to reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marke^ given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Traces Catastrophes DENVER OONOLIC Of Modern Society To Godless Leaders I ^ G I S T E R Sermon al Pallium Ceremony in Denver Cathe The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We dral Shows How Archbishop Shares in Have Also the International Nows Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) True Pastoral Office VOL. XU. No. 35. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, A PR IL 25, 1946. $1 PER YEAR Beware of false shepherds who scoff at God, call morality a mere human convention, and use tyranny and persecution as their staff. There is more than a mere state ment of truth in the words of Christ: “I am the Good Shep Official Translation of Bulls herd.” There is a challenge. Other shepherds offer to lead men through life but lead men astray. Christ is the only shepherd. Faithfully He leads men to God. This striking comparison of shepherds is the theme Erecting Archdiocese Is Given of the sermon by H. Em. Cardinal Samuel A. Stritch of Chicago in the Solemn Pon + ' + + tifical Mass in the Deliver Ca An official translation of the PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE rate, first of all, the Diocese of thedral this Thursday morning, Papal Bulls setting up the Arch EVENT Denver, together with its clergy April 25, at which the sacred pal diocese of Denver in 1941 was The things that seem to be more and people, from the Province of lium is being conferred upon Arch Bishop Lauds released this week by the Most helpful in procuring the greater Santa Fe. -

The Battle of Krbava Field, September 9Th, 1493

Borislav Grgin Filozofski fakultet sveučilišta u Zagrebu PreCeeDing the TRIPLEX CONFINIUM – the battLe oF krbava FieLD, sePteMber 9th, 1493 In this paper the attempt has been made to present a rounded view and oer some new interpretations re- garding one of the most recognizable and dramatic moments during the late medieval Croatian history. e Battle of Krbava Field, September 9th, 1493, dramatically shook the very foundations of medieval Croatia’s political and social structures. It stimulated creation of various texts written by its contemporaries and later commentators, who were discussing political, military and symbolical elements of the battle. e battle left a signicant imprint even in the collective memory of the Croatian people, thanks to the older historians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the interpretations of the battle in school manuals and teaching. e Krbava Battle, due to its real and symbolic signicance in Croatian˝history, still remains an interesting and challenging topic for the historians and for the wider public. erefore, it is not surprising that, due to incomplete and sometimes conicting and contradictory information in the sources, the interest for the battle and various interpretations reemerged during the last two decades and a half, after Croatia gained its independence. Key words: Krbava, Croatia, Ottomans, Late Middle Ages, Battle here are few events or moments in Croatian medieval history that are today present in Tnational collective memory. The Battle of Krbava Field, fought on September 9th, -

Christian-Muslim Relations a Bibliographical History History of Christian-Muslim Relations

Christian-Muslim Relations A Bibliographical History History of Christian-Muslim Relations Editorial Board David Thomas, University of Birmingham Sandra Toenies Keating, Providence College Tarif Khalidi, American University of Beirut Suleiman Mourad, Smith College Gabriel Said Reynolds, University of Notre Dame Mark Swanson, Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago Volume 24 Christians and Muslims have been involved in exchanges over matters of faith and morality since the founding of Islam. Attitudes between the faiths today are deeply coloured by the legacy of past encounters, and often preserve centuries-old negative views. The History of Christian-Muslim Relations, Texts and Studies presents the surviving record of past encounters in authoritative, fully introduced text editions and annotated translations, and also monograph and collected studies. It illustrates the development in mutual perceptions as these are contained in surviving Christian and Muslim writings, and makes available the arguments and rhetorical strategies that, for good or for ill, have left their mark on attitudes today. The series casts light on a history marked by intellectual creativity and occasional breakthroughs in communication, although, on the whole beset by misunderstanding and misrepresentation. By making this history better known, the series seeks to contribute to improved recognition between Christians and Muslims in the future. The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hcmr Christian-Muslim Relations A Bibliographical History Volume 7. Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and South America (1500-1600) Edited by David Thomas and John Chesworth with John Azumah, Stanisław Grodź, Andrew Newman, Douglas Pratt LEIDEN • BOstON 2015 Cover illustration: This shows the tuğra (monogram) of the Ottoman Sultan Murad III, affixed to a letter sent in 1591 to Sigismund III Vasa, king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. -

Cardinal Cajetan Renaissance Man

CARDINAL CAJETAN RENAISSANCE MAN William Seaver, O.P. {)T WAS A PORTENT of things to come that St. Thomas J Aquinas' principal achievement-a brilliant synthesis of faith and reason-aroused feelings of irritation and confusion in most of his contemporaries. But whatever their personal sentiments, it was altogether too imposing, too massive, to be ignored. Those committed to established ways of thought were startled by the revolutionary character of his theological entente. William of la Mare, a representa tive of the Augustinian tradition, is typical of those who instinctively attacked St. Thomas because of the novel sound of his ideas without taking time out to understand him. And the Dominicans who rushed to the ramparts to vindicate a distinguished brother were, as often as not, too busy fighting to be able even to attempt a stone by stone ex amination of the citadel they were defending. Inevitably, it has taken many centuries and many great minds to measure off the height and depth of his theological and philosophical productions-but men were ill-disposed to wait. Older loyalities, even in Thomas' own Order, yielded but slowly, if at all, and in the midst of the confusion and hesitation new minds were fashioning the via moderna. Tempier and Kilwardby's official condemnation in 1277 of philosophy's real or supposed efforts to usurp theology's function made men diffident of proving too much by sheer reason. Scotism now tended to replace demonstrative proofs with dialectical ones, and with Ockham logic and a spirit of analysis de cisively supplant metaphysics and all attempts at an organic fusion between the two disciplines. -

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome Jasenka Gudelj* Summary: Slavic people from South-Eastern Europe immigrated to Italy throughout the Early Modern period and organized them- selves into confraternities based on common origin and language. This article analyses the role of the images and architecture of the “national” church and hospital of the Schiavoni or Illyrian com- munity in Rome in the fashioning and management of their con- fraternity, which played a pivotal role in the self-definition of the Schiavoni in Italy and also served as an expression of papal for- eign policy in the Balkans. Schiavoni / Illyrians in Early Modern Italy and their confraternities People from the area broadly coinciding with present-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and coastal Montenegro, sharing a com- mon Slavonic language and the Catholic faith, migrated in a steady flux to Italy throughout the Early Modern period.1 The reasons behind the move varied, spanning from often-quoted Ottoman conquests in the Balkans or plague epidemics and famines to the formation of merchant and diplo- matic networks, as well as ecclesiastic or other professional career moves.2 Moreover, a common form of short-term travel to Italy on the part of so- called Schiavoni or Illyrians was the pilgrimage to Loreto or Rome, while the universities of Padua and Bologna, as well as monastery schools, at- tracted Schiavoni / Illyrian students of different social extractions. The first known organized groups described as Schiavoni are mentioned in Italy from the fifteenth century. Through the Early Modern period, Schiavoni / Illyrian confraternities existed in Rome, Venice, throughout the Marche region (Ancona, Ascoli, Recanati, Camerano, Loreto) and in Udine. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

The Life of Philip Thomas Howard, OP, Cardinal of Norfolk

lllifa Ex Lrauis 3liiralw* (furnlu* (JlnrWrrp THE LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CARDINAL OF NORFOLK. [The Copyright is reserved.] HMif -ft/ tutorvmjuiei. ifway ROMA Pa && Urtts.etOrl,,* awarzK ^n/^^-hi fofmmatafttrpureisJPTUS oJeffe Chori quo lufas mane<tt Ifouigionis THE LIFE OP PHILIP THOMAS HOWAKD, O.P. CARDINAL OF NORFOLK, GRAND ALMONER TO CATHERINE OF BRAGANZA QUEEN-CONSORT OF KING CHARLES II., AND RESTORER OF THE ENGLISH PROVINCE OF FRIAR-PREACHERS OR DOMINICANS. COMPILED FROM ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS. WITH A SKETCH OF THE EISE, MISSIONS, AND INFLUENCE OF THE DOMINICAN OEDEE, AND OF ITS EARLY HISTORY IN ENGLAND, BY FE. C. F, EAYMUND PALMEE, O.P. LONDON: THOMAS KICHAKDSON AND SON; DUBLIN ; AND DERBY. MDCCCLXVII. TO HENRY, DUKE OF NORFOLK, THIS LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CAEDINAL OF NOEFOLK, is AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED IN MEMORY OF THE FAITH AND VIRTUES OF HIS FATHEE, Dominican Priory, Woodchester, Gloucestershire. PREFACE. The following Life has been compiled mainly from original records and documents still preserved in the Archives of the English Province of Friar-Preachers. The work has at least this recommendation, that the matter is entirely new, as the MSS. from which it is taken have hitherto lain in complete obscurity. It is hoped that it will form an interesting addition to the Ecclesiastical History of Eng land. In the acknowledging of great assist ance from several friends, especial thanks are due to Philip H. Howard, Esq., of Corby Castle, who kindly supplied or directed atten tion to much valuable matter, and contributed a short but graphic sketch of the Life of the Cardinal of Norfolk taken by his father the late Henry Howard, Esq., from a MS. -

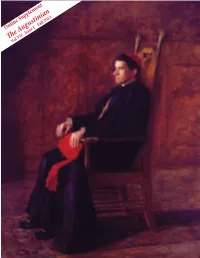

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

EPVLON 8.Indd

EPVLON ČASOPIS STUDENATA POVIJESTI SVEUČILIŠTA JURJA DOBRILE U PULI JOURNAL OF STUDENTS OF HISTORY OF UNIVERSITY JURAJ DOBRILA IN PULA ČASOPIS EPULON BROJ 8. PULA, 2012. ISSN-1334-1464 Izdavač Udruga studenata povijesti ISHA-Pula Uredništvo Davor Salihović (glavni urednik) Lana Krvopić Recenzenti dr. sc. Klara Buršić – Matijašić dr. sc. Igor Duda Prijevodi sažetaka Lana Krvopić Davor Salihović Naslovnica Davor Salihović Adresa uredništva Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Odjel za humanističke znanosti I. M. Ronjgova 1 52100 Pula, Hrvatska tel.: 099/574 – 3564 e-mail: [email protected] Časopis se objavljuje uz novčanu pomoć Sveučilišta Jurja Dobrile u Puli Naklada 200 primjeraka Tisak TISKARA NOVA - Galižana EPULON br. 8, časopis studenata povijesti Sveučilišta Jurja Dobrile u Puli Poštovano čitateljstvo, nakon nekoliko je godina od izdavanja posljednjeg, izašao i novi, osmi broj časopisa studenata povijesti - Epulon. Ovim se brojem uvode i neke novosti, a koje se tiču strukturiranja samog časopisa, odnosno njegova tematiziranja. Naime, najveća je novost vezana upravo za tematiziranje časopisa, koje je sve do ovoga broja bila gotovo tradicija, a ovim se brojem upravo ta tradicija, iz uredništvu poznatih i vrlo pragmatičnih razloga, prekida. Osim što je novi broj pisan bez teme vodilje, u ovome se broju neće naći niti naslovi pisani za poglavlje Et picturae historiam scribunt. Ipak, novi će broj i dalje dijelom podsjećati na njegove prethodnike, članci i prilozi; povijesni kolorit, velike bitke, ličnosti i zanimljivosti su i dalje tu, a slijedom je događaja ovaj broj postao svojevrsni temelj budućim izdanjima. Autori su radova, dakako, studenti Odsjeka za povijest našeg Sveučilišta, a njihov trud i recenzije naših profesora osiguravaju kvalitetu tekstova koje će te, nadamo se s velikim zanimanjem i oduševljenjem, iščitati iz novog izdanja Epulona. -

The History of the Augustinians As a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1965 The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province Joseph Anthony Linehan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Linehan, Joseph Anthony, "The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province" (1965). Dissertations. 776. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/776 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 1965 Joseph Anthony Linehan THF' RISTORI OF Tl[F, AUOUSTINIANS AS A Tt'ACHINO ormm IN THE JlIDWlmERN PlOVIlCR A nt. ..ertat.1on Submi toted to the Facul\7 ot the Gra.da1&te School of ~1a Un! wnd.ty in Partial PUlt1l.l.aent ot the Requirements tor the Degree of Docrtor of Fdnoation I would 11ke to thank the Reverend Daniel lI&rt1gan, O.S.A., who christened. th1s etud7. Reverend lf10bael Ibgan, D.S.A., who put it on ita feet, Dr. Jobn V.roz!'l1a.k, who taught it to walk. and Dr. Paul t1nieJ7, wm guided 1t. ThanlaI to st. Joseph Oupert1no who nlWer fails. How can one adequate~ thank his parente tor their sacrlf'loee, their 10... and their guidanoe. Is thank JOt! suttlc1ent tor a nil! who encourages when night school beoomea intolerable' 1bw do ,ou repay two 11 ttle glrls liM mat not 'bo'ther daddy in h1s "Portent- 1"OGIIl? Tou CIDIOt appreoiate tbe exoeUent teachers who .Mope )'Our future until you a~ an adult. -

January - March 2021

January - March 2021 JANUARY - MARCH 2010 Journal of Franciscan Culture Issued by the Franciscan Friars (OFM Malta) 135 Editorial EDITORIAL THE DEMOCRATIC DIMENSION OF AUTHORITY The Catholic Church is considered to be a kind of theocratic monarchy by the mass media. There is no such thing as a democratically elected government in the Church. On the universal level the Church is governed by the Pope. As a political figure the Pope is the head of state of the Vatican City, which functions as a mini-state with all the complexities of government Quarterly journal of and diplomatic bureaucracy, with the Secretariat of State, Franciscan culture published since April 1986. Congregations, Offices and the esteemed service of its diplomatic corps made up of Apostolic Nuncios in so many countries. On Layout: the local level the Church is governed by the Bishop and all the John Abela ofm Computer Setting: government structures of a Diocese. There is, of course, place for Raymond Camilleri ofm consultation and elections within the ecclesiastical structure, but the ultimate decisions rest with the men at the top. The same can Available at: be said of religious Orders, having their international, national http://www.i-tau.com and local organs of government. The Franciscan Order is also structured in this way, with the minister general, the ministers All original material is Copyright © TAU Franciscan provincial, custodes and local guardians and superiors. Communications 2021 Indeed, Saint Francis envisaged a kind of fraternity based on mutual co-responsibility. He did not accept the title of abbot or prior for the superiors of the Order, but wanted them to be “ministers and servants” of the brotherhood. -

Unityn Tinder¬

1r li ilsj i 4Wy T4TW 7 I a s C a- w f JENTUCKY IRISH AMERICAN ti OI 31 y VOLUME XXVNO 27 LOUISVILLE SATURDAY DECEMBER FIVE CENTS n PROTESTANT 19101PRICEY M DOWN I GLADSOME VOTED ROUTED ORPHANS LIMERICK Members of Division 4 Refutes Attacks Upon Ma Official Visits to councils I Paid No Heed to Able jority of People of in Kentucky Juris Made by Members of Two diction > Land 01 Christmas Ucllcctcd in Leader Smashing Blow Struck Against Ireland happy t ot Golden Yale Is Full Spirit Societies ol Young Faces of Young and Faction hi Irelands ot Interest to All Englishman J tho now year be Old Division 4 A 0 H held its final Polities A Protestant who hi People With there will Irishmen a meeting of 1910 at Bertrand nail on resided for nearly twenty years in an awakening of interest In tho Thursday night ot last week Owing Young Mens Institute throughout the South of Ireland has addcd his the Kentucky jurisdiction For this i r to the fact that the annual election testimony to of other From that corn Santa Claus Played No Favor ¬ Rich in Historic Itiiins It Happy Greetings From Pope Have Learned Wisdom spondentsj of thqy London Dally I and Prelates to Their Bitter Lessons ot the Chronicle who nave denounce ites On ills Happy the Goal of Many Unionist attacks upon the majority Trip Students Flocks Past of the people of Ireland During all the time that I have lived in Ire ¬ land he writes f jlrave experienced courtesy ¬ Restored Leg nothing but kindness and Great AVork oiYounjr Folks Is The Beautiful Shannon Drain Bishop ODonaghuo Has Joy Prediction