Sheldon Goldstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jniversity of Minnesota Northrop Memorial Auditorium 970 Cap and Gown Day Convocation .Hursday, May 14, 1970 at Eleven -Fifteen O'clock

IVERSITY OF MINNESOTA NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM I JNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM 970 CAP AND GOWN DAY CONVOCATION .HURSDAY, MAY 14, 1970 AT ELEVEN -FIFTEEN O'CLOCK TABLE OF CONTENTS The Cap and Gown Tradition ..... 1 Board of Regents and . Administrative Officers ... :..... ............ 2 Scholarships, Fellowships, Awards, and Prizes . .. .. .... .. 3 Student With Averages of B or Higher ............ ..... ................ ... .. , . 121 Academic Costume .. _ .. ....... 159 Order of events THE PROCESSIONAL The Frances Millet· Brown Memorial Bells, played by Janet Orjala, CLA '70, will be ·heard from Northrop Memorial Auditorium before the procession begins. The University of M-innesota Conce1t Band, Symphony Band I, and Symphony Band ll, conducted by Assistant Director of Band Fredrick Nyline, will play from the steps of Northrop Auditorium during the procession. The academic procession from the lower Mall into the Auditorium will be led by the Mace-Bearer, Professor James R. Jensen, D.D.S., M.S., Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs, School of Dentishy Following the Mace-Bearer will be candidates for degrees, ~arching by college, other honor students, the faculty, and the President. In the Auditorium, the audience is asked to remain seated so that all can see the procession. As the Mace-Bearer enters the Auditorium, Professor of Music ·and University Organist Heinrich Fleischer, Ph.D., will play the processional. The Mace-Bearer will present the Mace at the center of the stage. Candidates .for degrees will take places on 'either side of the middle aisle. Other honor students, includ ing freshman through graduate students, will be seated next to the candidates for degrees. When faculty members, marching last, have assembled on stage, the Mace-Bearer will place ·the Mace in its cradle, signaling the beginning of the ceremony. -

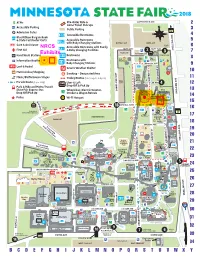

Natural Resources Conservation Service

2018 $ ATMs Pre-Order Ride & LARPENTEUR AVE Game Ticket Pick Ups Accessible Parking Public Parking # Admission Gates Accessible Restrooms Blue Ribbon Bargain Book & State Fair Poster Carts Accessible Restrooms with Baby Changing Stations BUFFALO LOT CAMEL LOT Care & Assistance Bicycle NRCS Accessible Restrooms with Family Lot First Aid HOYT AVE HOYT AVE AVE SNELLING & Baby Changing Facilities Metro TIGER LOT Mobility 3 ROOSTER LOT Drop Hand Wash StationsExhibits Restrooms Campground Expo The Pet Place X-Zone Information Booths Restrooms with Pavilions Baby Changing Stations MURPHY AVE Lost & Found SkyGlider Severe Weather Shelter $ Merchandise/Shopping Smoking – Designated Area Music/Performance Stages Giant Trolley Routes ( a.m.- p.m., p.m.) Sing OWL Along $ ST COSGROVE Parade Route ( p.m. daily) Uber & Lyft LOT Old Iron Show ST COOPER LEE AVE 4 Park & Ride and Metro Transit Drop O & Pick Up State Fair Express Bus Wheelchair, Electric Scooter, WAY ELMER DAN Eco UNDERWOOD ST UNDERWOOD Little Experience Drop O/Pick Up Stroller & Wagon Rentals Farm Progress AVE SNELLING Hands The Center North Police Wi-Fi Hotspot Woods B $ U Laser Encore’s F Laser Hitz O RANDALL AVE 18 Show R Bicycle Math D Lot RANDALL AVE On-A-Stick Fine Pedestrian & Arts Service Vehicle Entrance Center Great Family Fair Big Wheel CHARTER BUSES Baldwin ROBIN LOT Park Alphabet -H Forest Building WRIGHT AVE Park &Transit Ride Buses Hub $ Education Building SNELLING AVE SNELLING Horton ST COOPER Cosgrove Pavilions Kidway Home ST COSGROVE Stage Transit Hub at Heron Improvement Express Buses Park Building Grandstand Schilling $ $ Plaza & Amphitheater $ Ticket Oce Creative Elevator ST UNDERWOOD Activities History & 16 Elevator Buttery Visitors & Annex Heritage $ Grandstand SkyGlider House $ Plaza Center The Veranda $ DAN PATCH AVE $ West End $ U of M $ Market $ The MIDWAY $ FAN Garden Merchandise PARKWAY Skyride Health Central Fair 11 Mart WEST DAN PATCH AVE Ramp Carousel Libby Conf. -

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project

001 p-bp15-01-02a 002 003 004 005 MINNESOTA POLLUTION CONTROL AGENCY RMAD and Industrial Divisions Environment & Energy Section; Air Quality Permits Section The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project (1) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order and Authorization to Issue a Negative Declaration on the Need for an Environmental Impact Statement; and (2) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order, and Authorization to Issue Permit No. 05301050 -007. January 27, 2015 ISSUE STATEMENT This Board Item involves two related, but separate, Citizens’ Board (Board) decisions: (1) Whether to approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed University of Minnesota Twin Cities Campus Combined Heat and Power Project (Project). (2) If the Board approves a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS, decide whether to authorize the issuance of an air permit for the Project. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) staff requests that the Board approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS for the Project and approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order supporting the Negative Declaration. MPCA staff also requests that the Board approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order authorizing the issuance of Air Emissions Permit No. 05301050-007. Project Description. The University of Minnesota (University) proposes to construct a 22.8 megawatt (MW) combustion turbine generator with a 210 million British thermal units (MMBTU)/hr duct burner to produce steam for the Twin Cities campus. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Accessible Arts Calendar Summary 2019 Current Venues and Shows

Accessible Arts Calendar Summary 2019 Current Venues and Shows Updated 9-4-19 – The VSA Minnesota Accessible Arts Calendar lists arts events that proactively offer accessibility accommodations such as: ASL (American Sign Language Interpreting), AD (Audio Description), CC (Closed Captioning), OC (Open or Scripted Captioning), DIS (performers with disabilities), or SENS (Sensory-friendly accommodations) which are inclusive for children on the autism spectrum. The main Accessible Arts Calendar listings (emailed monthly through August 2019 and online at http://vsamn.org/community/calendar) offer descriptions of shows, authors, directors, describer & interpreter names, ticket prices, discounts, dates for Pay What You Can (PWYC), and more. This Current Venues and Shows list supplements the Accessible Arts Calendar. On our website as a Resource under Community (http://vsamn.org/community/resources-community/), it summarizes shows at arts venues across Minnesota: plays, concerts, exhibits, films, storytelling, etc. It’s limited to what we learn about and have time to include. The venues are organized alphabetically by Twin Cities venues and then by Greater Minnesota venues. They may offer accessible performances proactively or upon request. Words in GREEN identify some accessibility accommodations. We assume all auditoriums and bathrooms are wheelchair-accessible and theatres with fixed seating have assistive listening devices, unless noted otherwise. Both calendars will be discontinued after September 2019 when VSA Minnesota ceases operation. -

Founding Minnesota Public Radio

Saint John’s Abbey College of Saint Benedict / Saint John’s University Saint John’s Preparatory School Saint Benedict’s Monastery Sesquicentennial Benedictines in Central Minnesota — 150 Years Saint John's 150 > Features & Articles > Founding Minnesota Public Radio Founding Minnesota Public Radio In the early 1960s Father Colman Barry, then a history professor, was intrigued by the college’s student radio station, of which I was the manager. When I was about to graduate in 1964 and Colman was about to be appointed president, he asked me what I was planning to do. I told him I’d like to attend graduate school in either business or communications. With the support of Dr. Waldemar Wenner, Colman said, “Choose communications and we’ll send you to graduate school if you’ll agree to come back and begin a radio station for Saint John’s.” In the early 1960s Father Colman Barry, then a history professor, was intrigued by the college’s student radio station, of which I was the manager. When I was about to graduate in 1964 and Colman was about to be appointed president, he asked me what I was planning to do. I told him I’d like to attend graduate school in either business or communications. With the support of Dr. Waldemar Wenner, Colman said, “Choose communications and we’ll send you to graduate school if you’ll agree to come back and begin a radio station for Saint John’s.” I went off to Boston University and Stanford to study communications theory and law and hang out at WGBH in Boston and KQED in San Francisco, where some of the most advanced thinking in public broadcasting was occurring. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices

27662 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE applicant. Comments must be sent to Ch. 7, Anchorage, AK, and provides the PTFP at the following address: NTIA/ only public television service to over National Telecommunications and PTFP, Room 4625, 1401 Constitution 300,000 residents of south central Information Administration Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20230. Alaska. The purchase of a new earth [Docket Number: 960205021±7110±04] The Agency will incorporate all station has been necessitated by the comments from the public and any failure of the Telstar 401 satellite and RIN 0660±ZA01 replies from the applicant in the the subsequent move of Public applicant's official file. Broadcasting Service programming Public Telecommunications Facilities Alaska distribution to the Telstar 402R satellite. Program (PTFP) Because of topographical File No. 97001CRB Silakkuagvik AGENCY: National Telecommunications considerations, the latter satellite cannot Communications, Inc., KBRW±AM Post and Information Administration, be viewed from the site of Station's Office Box 109 1696 Okpik Street Commerce. KAKM±TV's present earth station. Thus, Barrow, AK 99723. Contact: Mr. a new receive site must be installed ACTION: Notice of applications received. Donovan J. Rinker, VP & General away from the station's studio location SUMMARY: The National Manager. Funds Requested: $78,262. in order for full PBS service to be Telecommunications and Information Total Project Cost: $104,500. On an restored. Administration (NTIA) previously emergency basis, to replace a transmitter File No. 97205CRB Kotzebue announced the solicitation of grant and a transmitter-return-link and to Broadcasting Inc., 396 Lagoon Drive applications for the Public purchase an automated fire suppression P.O. -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren. -

U of M Minneapolis Area Neighborhood Impact Report

Moving Forward Together: U of M Minneapolis Area Neighborhood Impact Report Appendices 1 2 Table of Contents Appendix 1: CEDAR RIVERSIDE: Neighborhood Profi le .....................5 Appendix 15: Maps: U of M Faculty and Staff Living in University Appendix 2: MARCY-HOLMES: Neighborhood Profi le .........................7 Neighborhoods .......................................................................27 Appendix 3: PROSPECT PARK: Neighborhood Profi le ..........................9 Appendix 16: Maps: U of M Twin Cities Campus Laborshed ....................28 Appendix 4: SOUTHEAST COMO: Neighborhood Profi le ...................11 Appendix 17: Maps: Residential Parcel Designation ...................................29 Appendix 5: UNIVERSITY DISTRICT: Neighborhood Profi le ......... 13 Appendix 18: Federal Facilities Impact Model ........................................... 30 Appendix 6: Map: U of M neighborhood business district ....................... 15 Appendix 19: Crime Data .............................................................................. 31 Appendix 7: Commercial District Profi le: Stadium Village .....................16 Appendix 20: Examples and Best Practices ..................................................32 Appendix 8: Commercial District Profi le: Dinkytown .............................18 Appendix 21: Examples of Prior Planning and Development Appendix 9: Commercial District Profi le: Cedar Riverside .................... 20 Collaboratives in the District ................................................38 Appendix 10: Residential -

BUILDING U.S.-CHINA BRIDGES China Center Annual Report 2007-08 Inside from the Director

BUILDING U.S.-CHINA BRIDGES China Center Annual Report 2007-08 Inside From the Director........................................................... 1 Students and Scholars .................................................... 2 Faculty ............................................................................ 3 K-12 Initiatives .............................................................. 4 Training Programs .......................................................... 5 Griffin Lecture ................................................................ 6 Community Engagement ............................................... 7 Recruitment .................................................................... 8 To Our Chinese Friends ................................................. 9 Bridging Relationships ................................................. 10 Contributors ................................................................. 11 Corporate Partnership / Budget .................................... 12 CCAC and China Center Office Information ............... 13 Note about Chinese names: The China Center’s policy is to print an individual’s name according to the custom of the place where they live (e.g., family name first for a person who lives in China). On the Cover 1 1. A Bridge in China 2 3 2. China Center Dragon Boat team (page 7) 3. Participants in the First Sino-US Education Forum (page 3) 4 4. Students in Northrop Auditorium for China Day (page 4) 5. Training program participants at their graduation reception (page 5) 5 6 6. Training -

Sheila Smith, 651-251-0868 Executive Director, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts Kathy Mouacheupao, 651-645-0402 Executive Director, Metropolitan Regional Arts Council

3/12/19 Contacts: Sheila SMith, 651-251-0868 Executive Director, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts Kathy Mouacheupao, 651-645-0402 Executive Director, Metropolitan Regional Arts Council Creative Minnesota 2019 Study Reveals Growth of Arts and Culture Sector in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area Minnesota SAINT PAUL, MN: Creative Minnesota, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts and the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council released a new study today indicating that the arts and culture sector in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area is groWing. “The passage of the Legacy AMendment in Minnesota allowed the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council and Minnesota State Arts Board to increase support for the arts and culture in this area, and that has had a big iMpact,” said Sheila SMith, Executive Director of Minnesota Citizens for the Arts. “It’s wonderful to see how the access to the arts has groWn in this area over tiMe.” The Legacy Amendment was passed by a statewide vote of the people of Minnesota in 2008 and created dedicated funding for the arts and culture in Minnesota. The legislature appropriates the dollars from the Legacy Arts and Culture Fund to the Minnesota State Arts Board, Regional Arts Councils, Minnesota Historical Society and other entities to provide access to the arts and culture for all Minnesotans. “Creative Minnesota’s new 2019 report is about Minnesota’s arts and creative sector. It includes stateWide, regional and local looks at nonprofit arts and culture organizations, their audiences, artists and creative Workers. This year it also looks at the availability of arts education in Minnesota schools,” said SMith. “We also include the results of fifteen local studies that show substantial economic iMpact from the nonprofit arts and culture sector in every corner of the state, including $4.9 million in the City of Eagan, $2.4 million in the City of Hastings, 11 million in the City of Hopkins, $4 million in the Maple Grove Area, $541 million in the City of Minneapolis, and $1.5 million in the City St.