Berkshire County Education Task Force Planning Study, Phase One Final Report, October 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

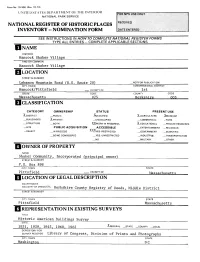

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

RICHMOND Massachusetts

Town of RICHMOND Massachusetts Annual Report 2014 RICHMOND TOWN HALL Monday through Friday – 8:30 – 2:30 (413) 698-3355 Town Administrator – Matt Kerwood 698-3882 Monday through Friday – 9:00 – 4:00 Tax Collector – Frederick Schubert 698-3315 Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday – 9:00 – Noon Town Clerk – Kate Zahn 698-3555 Tuesday through Friday – 8:30 – 1:30 Town Treasurer – Paul A. Lisi, Jr. 698-3556 Monday, Thursday – 9:00 am – 4:00 Town Secretary – Kate Zahn 698-3355 Monday through Friday – 8:30 – 1:30 Board of Selectmen 1st, 2nd and 4th Wednesday – 6:00 pm Board of Assessors 2nd Wednesday – 6:30 pm Board of Health 1st Tuesday – 6:30 pm Planning Board 2nd Monday – 6:30 pm Conservation Commission 2nd Tuesday – 7:00 pm Building Inspector – Paul Greene 1st, 2nd and 4th Wednesday – 10:30 am - 12:00 Zoning Enforcement Officer – Craig Swinson 698-2525 1st, 2nd and 4th Wednesday – 10:30 am - 12:00 pm Chief of Police – William Bullett (442-3693) 2nd and 4th Wednesday – 7:30 pm Animal Control Officer John Springstube 232-7038 Richmond Annual Town Report - 2014 In Memoriam Each year we honor town officers and employees who have passed away. In 2014 we lost the following: Helen Kinsley Former Town Clerk Milton Bass Former Moderator Theresa Forget Former Community Health Association Board Member This town report is dedicated to their memory. Town of Richmond Massachusetts ANNUAL REPORTS of the Town Officers For the Year Ending December 31, 2014 FY 2014 Tax Rate – $ 10.29 FY 2014 Total Valuation – $ 421,249,215 FY 2014 Total Tax Levied – $ 4,334,654.43 Population Local Census – 1,470 Population Federal Census 2010 – 1,475 Registered Voters – 1,069 Area of Town – 19.07 Square Miles Richmond Annual Town Report - 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Ambulance Service . -

Vol. 80 No. 1 January-March 2017 Published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB

The Cloudsplitter Vol. 80 No. 1 January-March 2017 published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB The Cloudsplitter is published quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and is distributed to the membership. All issues (January, April, July, and October) feature activities schedules, trip reports, and other articles of interest to the outdoor enthusiast. All outings should now be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org. Echoes should be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org with your login information. The Albany Chapter may be Please send your address and For Club orders & membership For Cloudsplitter related issues, reached at: phone number changes to: call (800) 395-8080 or contact the Editors at: Albany Chapter ADK Adirondack Mountain Club e-mail: [email protected] The Cloudsplitter Empire State Plaza 814 Goggins Road home page: www.adk.org Kathryn Behuniak: P.O. Box 2116 Lake George, NY 12845-4117 [email protected] Albany, NY 12220 phone: (518) 668-4447 or home page: fax: (518) 668-3746 Ann Burns: www.adk-albany.org [email protected] Submission deadline for the next issue of The Cloudsplitter is February 15, 2017 and will be for the months of April, May, and June, 2017. Many thanks to Gail Carr for her cover sketch of “Two Mourning Doves.” January 4, February 1, March 1 (1st Wednesdays) Business Meeting of Chapter Officers and Committees 6:00 p.m. at Little’s Lake in Menands Chapter members are encouraged to attend - please call Jim Slavin at 434-4393 Chapter Meetings are held at the West Albany Fire House (Station #1), 113 Sand Creek Road, Albany. -

Infrastructure and Services

Infrastructure and Services An Element of Sustainable Berkshires, Long-Range Plan for Berkshire County Adopted 3.20.14 Berkshire Regional Planning Commission Sustainable Berkshires is a project of the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission. The work that provided the basis for this publication was supported by funding under an award with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The author and publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS REGIONAL CONSORTIUM 1Berkshire City of North Adams Stuart Chase, President & CEO Mike Nuvallie, Housing and Projects Coordinator Berkshire Community Action Council Compact for Education Kim McMann, Director of Planning Denise Richardello, V.P. of Enrollment Management Mary Nash (Alternate), Project Coordinator Berkshire County Regional Housing Authority Brad Gordon, Executive Director & Staff Attorney Housatonic Heritage Dan Bolognani, Executive Director Berkshire County Selectmen’s Association Julie Hannum MA Fisheries and Wildlife Andrew Madden, District Manager Berkshire Health Systems Ruth Blodgett, Vice President, BHS Planning and Multicultural BRIDGE Development Gwendolyn Hampton VanSant, Executive Director & Ed Perlak (Alternate), Public Health Grants Founder Administrator Lori Gazzillo (Alternate), Board President Berkshire Housing Development Corporation -

Pittsfield and October Mountain Trail System Plan

TRAIL SYSTEM PLAN DCR’s Pittsfield and October Mountain State Forests Contents Page Section 1. Introduction 4 1.1. Introduction 4 1.2. Mission of the Department of Conservation and Recreation 5 1.3. Trail System Planning 5 1.4. The Planning Process 5 Section 2. Existing Conditions 7 2.1. Natural Resources 7 2.2. Cultural History 8 2.3. Recreational Resources 9 2.4. Ownership and Management 9 2.5. Current Trail System 10 2.6. Trail Conditions 11 2.7. Recreational Conflict 12 Section 3. Goals, Features and Experiences 15 3.1. Trail System Management Goals 15 3.2. Features, Access Points and Connections 16 3.3. Recreational Experiences and Expectations 18 Section 4. Sensitive Natural and Cultural Resources 21 4.1. Sensitive Sites and Resources 21 4.2. Ecological Impacts of Trail Activities 22 Section 5. Management, Staffing and Partners 24 5.1 DCR Staffing 24 5.2 Partner Resources 24 5.3 Permitting Procedures 25 Section 6. Management Recommendations 27 COMBINED RECOMMENDATIONS 6.1. Engage an Experienced OHV Planning Consultant to Develop an OHV Funding, 27 Maintenance and Management Plan 6.2. Expand Regional and Complex Staffing to Successfully Manage and Maintain these 27 Multi-Use Trail Systems 6.3. Implement Approved Trail Recommendations in Cooperation with Stewardship Partners 27 6.4. Produce a New Maps for PSF and OMSF 28 6.5. Create Disincentives to Help Halt Illegal Trail Building 28 PITTSFIELD STATE FOREST 6.6. Enhance Trail Marking, Wayfinding and User Information 28 6.7. Repair and Maintain Priority Trails and Trail Segments 28 6.8. -

DCR's Pittsfield and October Mountain State Forests

TRAIL SYSTEM PLAN DCR’s Pittsfield and October Mountain State Forests Contents Page Section 1. Introduction 4 1.1. Introduction 4 1.2. Mission of the Department of Conservation and Recreation 5 1.3. Trail System Planning 5 1.4. The Planning Process 5 Section 2. Existing Conditions 7 2.1. Natural Resources 7 2.2. Cultural History 8 2.3. Recreational Resources 9 2.4. Ownership and Management 9 2.5. Current Trail System 10 2.6. Trail Conditions 11 2.7. Recreational Conflict 12 Section 3. Goals, Features and Experiences 14 3.1. Trail System Management Goals 14 3.2. Features, Access Points and Connections 15 3.3. Recreational Experiences and Expectations 17 Section 4. Sensitive Natural and Cultural Resources 20 4.1. Sensitive Sites and Resources 20 4.2. Ecological Impacts of Trail Activities 21 Section 5. Management, Staffing and Partners 23 5.1 DCR Staffing 23 5.2 Partner Resources 23 5.3 Permitting Procedures 24 Section 6. Management Recommendations 26 COMBINED RECOMMENDATIONS 6.1. Engage an Experienced OHV Planning Consultant to Develop an OHV Funding, 26 Maintenance and Management Plan 6.2. Expand Regional and Complex Staffing to Successfully Manage and Maintain these 26 Multi-Use Trail Systems 6.3. Implement Approved Trail Recommendations in Cooperation with Stewardship Partners 26 6.4. Produce a New Maps for PSF and OMSF 27 6.5. Create Disincentives to Help Halt Illegal Trail Building 27 PITTSFIELD STATE FOREST 6.6. Enhance Trail Marking, Wayfinding and User Information 27 6.7. Repair and Maintain Priority Trails and Trail Segments 27 6.8. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or Country -- America -- North America -- United States -- Northe

G3701.S UNITED STATES. HISTORY G3701.S .S1 General .S12 Discovery and exploration Including exploration of the West .S2 Colonial period .S26 French and Indian War, 1755-1763 .S3 Revolution, 1775-1783 .S4 1783-1865 .S42 War of 1812 .S44 Mexican War, 1845-1848 .S5 Civil War, 1861-1865 .S55 1865-1900 .S57 Spanish American War, 1898 .S6 1900-1945 .S65 World War I .S7 World War II .S73 1945- 88 G3702 UNITED STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G3702 ETC. .C6 Coasts .G7 Great River Road .L5 Lincoln Highway .M6 Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail. Mormon Trail .N6 North Country National Scenic Trail .U5 United States Highway 30 .U53 United States Highway 50 .U55 United States Highway 66 89 G3707 EASTERN UNITED STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3707 FEATURES, ETC. .A5 Appalachian Basin .A6 Appalachian Mountains .I4 Interstate 64 .I5 Interstate 75 .I7 Interstate 77 .I8 Interstate 81 .J6 John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail .N4 New Madrid Seismic Zone .O5 Ohio River .U5 United States Highway 150 .W3 Warrior Trail 90 G3709.32 ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3709.32 FEATURES, ETC. .A6 Appalachian Trail .A8 Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway .C6 Coasts .I5 Interstate 95 .O2 Ocean Hiway .P5 Piedmont Region .U5 United States Highway 1 .U6 United States Highway 13 91 G3712 NORTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3712 FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Coasts .C8 Cumberland Road .U5 United States Highway 22 92 G3717 NORTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3717 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Coasts .T3 Taconic Range .U5 United States Highway 202 93 G3722 NEW ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G3722 ETC. .C6 Coasts .C62 Connecticut River 94 G3732 MAINE. -

BC.PH.Coll.1: S. Waldo Bailey Negatives of the Berkshires (1898

THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to S. Waldo Bailey Negatives of the Berkshires, 1898-1961 BC.PH.Coll.1 by Miriam B. Spectre September 2011 Last updated: April 2018 Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 S. Waldo Bailey Negatives of the Berkshires - 1 Extent: 6 card boxes Other storage formats: stored in Oversize Linear feet: 6.0 Copyright © 2013 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Gift of E. Priscilla Bailey, 2011. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The S. Waldo Bailey Negatives of the Berkshires are the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. CITE AS S. Waldo Bailey Negatives of the Berkshires. The Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. BIOGRAPHICAL MATERIAL Known as “Berkshire County’s closest approximation to Henry David Thoreau”, S. Waldo Bailey was the first warden of Bartholomew’s Cobble. Before the Trustees acquired the property in 1946, Bailey had long been drawn to the property, noting in 1920 that “it was a pleasure to find such a rare rock garden”. Bailey was an amateur naturalist, whose interests ranged from archaeology to botany. As a member of the American Fern Society, Bailey impressed Charles A. Weatherby, the curator of the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University, with his many excursions in the Berkshires, articles in The Auk and the American Fern Journal, and his photographs of plants and landscapes. When the Trustees were looking for a botanist warden to lay out and clear paths, greet visitors, and show off the flora at Bartholomew’s Cobble, Weatherby believed that Bailey would be the perfect choice. -

Berkshire County Education Task Force Planning Study

Berkshire County Education Task Force Planning Study Phase Two Report: Scenarios Developed, Described and Modeled July 18, 2017 Helping Schools and Students Thrive Background and Context The Berkshire County Education Task Force (BCETF) is a group of current and former school administrators and educators, school committee members, town administrators, and local business leaders, higher education officials and others who have met 32 times since July, 2015 to explore ways Berkshire County can address the challenge of erosion of educational quality due to declining student enrollment and revenues that are not keeping pace with costs. In February 2017 the Task Force framed its purpose this way: We believe that a high quality education is the right of every child in Berkshire County. We are exploring and seeking options that will provide the best opportunities and outcomes from and for our schools and school districts at a time of declining population and resources. …(Our) intent… is to develop and recommend solutions that: § Enhance access, diversity, breadth and quality of educational programs for children countywide so they are fully prepared for college, career and a life here in the Berkshires; § Create economies of scale (financial savings) through new collaborations, technologies, partnerships, and regional agreements between and among towns/cities and districts; § Advance new investments in collaborative solutions (e.g. expanded pre-K programming or special education services) that enhance educational services and opportunities for -

ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB

The Cloudsplitter Vol. 78 No. 3 July-September 2015 published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB The Cloudsplitter is published quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and is distributed to the membership. All issues (January, April, July, and October) feature activities schedules, trip reports, and other articles of interest to the outdoor enthusiast. All outings should now be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org . Echoes should be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org with your login information. The Albany Chapter may be Please send your address and For Club orders & membership For Cloudsplitter related issues, reached at: phone number changes to: call (800) 395-8080 or contact the Editor at: Albany Chapter ADK Adirondack Mountain Club e-mail: [email protected] The Cloudsplitter Empire State Plaza 814 Goggins Road home page: www.adk.org c/o Karen Ross P.O. Box 2116 Lake George, NY 12845-4117 7 Bird Road Albany, NY 12220 phone: (518) 668-4447 Lebanon Spgs., NY 12125 home page: fax: (518) 668-3746 e-mail: [email protected] www.adk-albany.org Submission deadline for the next issue of The Cloudsplitter is August 15, 2015 and will be for the months of October, November, and December, 2015. Many thanks to Gail Carr for her cover sketch of a patriotic view of North and South Lakes in the Catskills. September 2 (1st Wednesdays) Business Meeting of Chapter Officers and Committees 6:00 p.m. at Little’s Lake in Menands Chapter members are encouraged to attend - please call Tom Hart at 229-5627 There are no Chapter Meetings held during July, August, or September MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN It seems we are in the midst of a resurgence in outdoor recreation. -

Stories of the Berkshires Kimberly Bolduc Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2017 A Monumental History: Stories of the Berkshires Kimberly Bolduc Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Bolduc, Kimberly, "A Monumental History: Stories of the Berkshires" (2017). Honors Theses. 9. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/9 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Monumental History: Stories of the Berkshires By Kimberly Bolduc ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of English Union College June 2017 Bolduc ii Abstract BOLDUC, KIMBERLY A. A Monumental History: Stories of the Berkshires. Department of English, June 2017. ADVISORS: Andrew Burkett, Bernhard Kuhn A Monumental History: Stories of the Berkshires is a creative-nonfiction work focusing on stories surrounding forgotten monuments in the Berkshire region of western Massachusetts. The Berkshires exhibit a distinct regional culture that has set them apart from the rest of Massachusetts and indeed from the rest of the rural and urban United States. As one of the first American frontiers, the region was settled by self-reliant and determined pioneers who had to endure harsh environments, Native American unrest, wars, and political and religious disturbances and disagreements. Utopian communities like the Shakers would settle in the Berkshires, drawn by their promise of frontier religious freedoms.