International Production Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

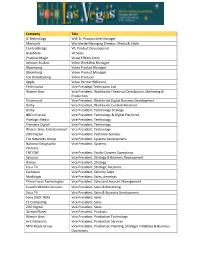

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft Worldwide Managing Director, Media & Cable Contentbridge VP, Product Development GrayMeta VP Sales Practical Magic Visual Effects Artist Amazon Studios Video Workflow Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Fox Broadcasting Video Producer Apple Video Partner Relations Technicolor Vice Presidept Technicolor Ltd Warner Bros. Vice President, Worldwide Theatrical Distribution, Marketing & Production Paramount Vice President, Worldwide Digital Business Development Dolby Vice President, Worldwide Content Relations Dolby Vice President, Technology Strategy NBCUniversal Vice President, Technology & Digital Platforms Pixelogic Media Vice President, Technology Premiere Digital Vice President, Technology Warner Bros. Entertainment Vice President, Technology ZOO Digital Vice President, Technical Services Fox Networks Group Vice President, Systems Development National Geographic Vice President, Systems Partners TNT/TBS Vice President, Studio Content Operations Synovos Vice President, Strategy & Business Development Disney Vice President, Strategy You.i TV Vice President, Strategic Accounts Cartesian Vice President, Security Sales MarkLogic Vice President, Sales, Americas Prime Focus Technologies Vice President, Sales and Account Management Crawford Media Services Vice President, Sales & Marketing You.i TV Vice President, Sales & Business Development Sony DADC NMS Vice President, Sales T2 Computing Vice President, Sales ZOO Digital Vice President, Sales -

Paramount Pictures and Dreamworks Pictures' "GHOST in the SHELL" Is in Production in New Zealand

April 14, 2016 Paramount Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures' "GHOST IN THE SHELL" is in Production in New Zealand HOLLYWOOD, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Paramount Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures have announced that production is underway on "GHOST IN THE SHELL," starring Scarlett Johansson ("AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON," "LUCY") and directed by Rupert Sanders ("SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN"). The film is shooting in Wellington, New Zealand. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160414005815/en/ Paramount Pictures will release the film in the U.S. on March 31, 2017. The film, which is based on the famous Kodansha Comics manga series of the same name, written and illustrated by Masamune Shirow, is produced by Avi Arad ("THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 1 & 2," "IRON MAN"), Ari Arad ("GHOST RIDER: SPIRIT OF VENGEANCE"), and Steven Paul ("GHOST RIDER: SPIRIT OF VENGEANCE"). Michael Costigan ("PROMETHEUS"), Tetsu Fujimura ("TEKKEN"), Mitsuhisa Ishikawa, whose animation studio Production I.G produced the Japanese "GHOST IN THE SHELL" film and television series, and Jeffrey Silver ("EDGE OF TOMORROW," "300") will executive produce. Scarlett Johansson plays the Major in Ghost in the Shell from Paramount Pictures Based on the internationally-acclaimed sci-fi and DreamWorks Pictures in Theaters March 31, 2017. (Photo: Business Wire) property, "GHOST IN THE SHELL" follows the Major, a special ops, one-of-a-kind human-cyborg hybrid, who leads the elite task force Section 9. Devoted to stopping the most dangerous criminals and extremists, Section 9 is faced with an enemy whose singular goal is to wipe out Hanka Robotic's advancements in cyber technology. -

Glenn-Garland-Editor-Credits.Pdf

GLENN GARLAND, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. WELCOME TO THE BLUMHOUSE: BLACK BOX Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour Amazon / Blumhouse Productions EP: Jay Ellis, Jason Blum, Aaron Bergman PARADISE CITY*** (series) Ash Avildsen Sumerian Films EP: Lorenzo Antonucci PREACHER (season 3) Various AMC / Sony Pictures Television EP: Sam Catlin, Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg ALTERED CARBON** (series) Various Netflix / Skydance EP: Laeta Kalogridis, James Middleton, Steve Blackman STAN AGAINST EVIL (series) Various IFC / Radical Media EP: Dana Gould, Frank Scherma, Tom Lassally BANSHEE (series) Ole Christian Madsen HBO / Cinemax Magnus Martens EP: Alan Ball THE VAMPIRE DIARIES (series) Various CW / Warner Bros. Television EP: Julie Plec, Kevin Williamson Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BROKE Carlyle Eubank Wild West Entertainment Prod: Wyatt Russell, Alex Hertzberg, Peter Billingsley THE TURNING Floria Sigismondi Amblin Partners 3 FROM HELL Rob Zombie Lionsgate FAMILY Laura Steinel Sony Pictures / Annapurna Pictures Official Selection: SXSW Film Festival Prod: Kit Giordano, Sue Naegle, Jeremy Garelick SILENCIO Lorena Villarreal 5100 Films / Prod: Beau Genot 31 Rob Zombie Lionsgate / Saban Films Official Selection: Sundance Film Festival Prod: Mike Elliot, Andy Gould THE QUIET ONES John Pogue Lionsgate / Exclusive Media LORDS OF SALEM Rob Zombie Blumhouse / Anchor Bay Entertainment LOVE & HONOR Danny Mooney IFC Films / Red 56 HALLOWEEN 2 Rob Zombie Dimension Films BUNRAKU* Guy Moshe Snoot Entertainment Official -

Media Release Dreamworks Studios, Participant Media

MEDIA RELEASE DREAMWORKS STUDIOS, PARTICIPANT MEDIA, RELIANCE ENTERTAINMENT AND ENTERTAINMENT ONE FORM AMBLIN PARTNERS, A NEW FILM, TELEVISION AND DIGITAL CONTENT CREATION COMPANY Steven Spielberg Also an Investor in Amblin Partners Mumbai, December 17, 2015: Steven Spielberg, Principal Partner, DreamWorks Studios, Jeff Skoll, Chairman, Participant Media, Anil Ambani, Chairman, Reliance Group and Darren Throop, President and Chief Executive Officer, Entertainment One (eOne) announced today the formation of Amblin Partners, a new film, television and digital content creation company. The new company will create content using the Amblin, DreamWorks Pictures and Participant brands and leverage their power and broad awareness to tell stories that appeal to a wide range of audiences. Participant Media will remain a separate company that continues to independently develop, produce and finance projects with socially relevant themes. Amblin Partners will be led by CEO Michael Wright and President and COO Jeff Small. In addition, Amblin Television will become a division of Amblin Partners and continues to be run by co- presidents Justin Falvey and Darryl Frank, who maintain their longtime leadership roles. They join Producer Kristie Macosko Krieger and President of Production Holly Bario on the film side, to complete Amblin Partners’ senior management team. David Linde, Chief Executive Officer of Participant Media, and Participant’s narrative feature team, led by Executive Vice President Jonathan King, will work closely with Amblin Partners to develop and produce specific content for the new venture in addition to exploring opportunities for co-productions and other content. In making the announcement about Amblin Partners, Mr. Spielberg said, “We are thrilled to partner with Jeff Skoll, Participant Media, and to continue our prolific relationship. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

Praesens-Film AG Präsentiert PRODUCTION NOTES

Praesens-Film AG präsentiert X + Y PRODUCTION NOTES Ab 9. April im Kino Dauer: 111 Minutes Pressekontakt: Filmbüro, Valerio Bonadei, [email protected], +41 79 653 65 03 1 CAST Asa Butterfield……………………………..……………………….... Nathan Ellis Rafe Spall………………………………………….……………Martin Humphreys Sally Hawkins…………………………………………………………………Julie Ellis Eddie Marsan……………………………………………………….Richard Grieve Jo Yang……………………………………………………………………….Zhang Mei Martin McCann……………………………………………………….Michael Ellis Jake Davies…………………………………………..…………………Luke Shelton Alex Lawther…………………………………………………………..Isaac Cooper Alexa Davies…………………………………….……………………Rebecca Dunn Orion Lee…………………………………………………………………Deng Laoshi Percelle Ascott………………………………………………………….Ben Morgan Suraj Rattu……………………………..…………………………………Pav Kamdar Edward Baker-Close…….………………………………Nathan (9 years old) 2 X+Y Synopsis A young maths genius sees logic thwarted by one truly baffling equation: love. Teenage maths prodigy Nathan (Asa Butterfield) struggles when it comes to building relationships with other people, not least with his mother, Julie (Sally Hawkins). In a world difficult to comprehend, he finds comfort in numbers. And when Nathan is taken under the wing of unconventional and anarchic teacher, Mr. Humphreys (Rafe Spall), the pair forge an unusual friendship. Eventually, Nathan’s talents win him a place on the UK National team at the International Mathematics Olympiad (IMO) and the team travel to a training camp in Taiwan, under the supervision of squad leader Richard (Eddie Marsan). In unfamiliar surroundings, Nathan is confronted by a series of unexpected challenges — not least the unfamiliar feelings he begins to experience for his Chinese counterpart, the beautiful Zhang Mei (Jo Yang), feelings that develop when the young mathematicians return to England for the IMO, held at Trinity College, Cambridge. From suburban England to bustling Taipei and back again, this original and heart-warming film tracks the funny and complex relationships that Nathan builds, as he is confronted by the irrational nature of love. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Ak Büyü / Sh'chur Geç Evlilik / Late Marriage Or (Hazinem) / Or (My Treasure)

Pera Film, toplumun sınırlarına karşı özgürlüğü için mücadele eden çarpıcı kadın karakterleri canlandırmış Ronit Elkabetz’e saygı duruşu niteliğinde bir seçki sunuyor. Ak Büyü / Sınırların Ötesi, Elkabetz’in aile, gelenekler, evlilik ve devletin kurumsal dayatmaları Sh’Chur karşısında özgürlükleri için mücadele eden ve bu nedenle toplumda sıradışı kabul edilen kadınlarla ilgili olarak yarattığı bir dizi unutulmaz karakter sayesinde, hem İsrail Yönetmen / Director: Shmuel Hasfari hem de Avrupa sinemasında bir dönüşüme imza attığı çalışmalarını izleyiciyle Oyuncular / Cast: Gila Almagor, Ronit Elkabetz, 7 – 28 Kasım | November 2018 Eti Adar, Hanna Azoulay Hasfari buluşturuyor. İsrail / Israel, 1994, 98’, renkli / color İbranice; Türkçe altyazılı / Sınırların Ötesi programı, Elkabetz’in kimi zaman oyuncu kimi zaman da yönetmen Hebrew with Turkish subtitles olarak yer aldığı, kariyerinde büyük bir öneme sahip dokuz filme yer veriyor. İsrail’de yaşayan Fas topluluğunun renkli ve tutku dolu kültürünü betimleyen Ak Büyü, aile ve Ak Büyü, İsrail’de yaşayan Fas topluluğunun renkli ve tutku dolu kültürüne evlilik kavramlarını genç bir adamın yaşadıkları üzerinden trajikomik bir anlatıyla odaklanıyor. Film, tamamen Batılılaşmış genç bir Sabra kızı olan 13 yaşındaki gösteren Geç Evlilik, hayatı üzerindeki tüm kontrolünü yitirmiş Ruthie’yle, ona başka Rachel’in aile üyelerinin düzenli olarak yaptıkları ak büyüyü (Sh’Chur) anlamaya ve bir iş bulmaya çalışan kızının hikayesini anlatan Or (Hazinem), hem eşi hem de onunla uzlaşmaya çalışmasını anlatıyor. -

Stephens Plays: 2: One Minute; Country Music; Motortown; Harper

Simon Stephens Plays: 2 One Minute, Country Music Motortown, Pornography, Sea Wall One Minute: ‘Set in London in the aftermath of the disappearance of an eleven-year-old girl, One Minute brings together the girl’s mother, an unreliable witness, a student/barmaid and two investigating officers . the writing cleverly suggests how much the characters would like to connect but never really can.’ Guardian Country Music ‘spotlights four fateful moments in the life of Jamie Carris, an engaging but violent south Londoner. The play unfolds in a series of tightly focused two-handers, set before, during and after the prison sentences he has served for glassing one man and for killing another.’ Independent Motortown: ‘Danny – a squaddie who has served in Basra – is bringing the war back home [to] an England where the “war on terror” has become a war waged using the tactics of the terrorists. It is also a place of dubious moralities, small-time arms dealers and middle-class swingers and anti-war protesters. A searingly honest play written with a deadly coiled energy.’ Guardian Pornography: ‘Set in July 2005, between the announcement that London had been awarded the Olympics and the July 7 bombings, it tells seven entwining stories, including the imagined story of one of the bombers journeying towards London to commit an act of terrorism.’ Guardian Sea Wall: ‘A quietly gripping monologue about grief and belief . this play is like a deceptive calm blue sea beneath which lurks a ferocious riptide of sorrow.’ Guardian Simon Stephens is a British writer whose theatrical career began in the literary department of the Royal Court Theatre where he ran its Young Writers’ Programme. -

The Limehouse Golem’ by

PRODUCTION NOTES Running Time: 108mins 1 THE CAST John Kildare ................................................................................................................................................ Bill Nighy Lizzie Cree .............................................................................................................................................. Olivia Cooke Dan Leno ............................................................................................................................................ Douglas Booth George Flood ......................................................................................................................................... Daniel Mays John Cree .................................................................................................................................................... Sam Reid Aveline Mortimer ............................................................................................................................. Maria Valverde Karl Marx ......................................................................................................................................... Henry Goodman Augustus Rowley ...................................................................................................................................... Paul Ritter George Gissing ................................................................................................................................ Morgan Watkins Inspector Roberts ............................................................................................................................... -

College of Jewish Studies Program Fall 2017

September 22-28, 2017 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLVI, Number 38 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK College of Jewish Studies Program fall 2017: “Divided by Victory: The Legacy of the Six-Day War” The Six-Day War has been called “one The fall 2017 program of the College of on Jewish history and contemporary Jewish and the Significance of 1948.” Libman is of the most significant events in modern Jewish Studies will focus on aspects of the life. He has been widely cited in the media a literary scholar and cultural historian Israeli history.” As a result of the Israeli legacy of the Six-Day War 50 years later. and on three occasions has been named to specializing in the literature and cultural victory, Jews were in control of Jerusalem The first lecture in the College of Jewish the Forward’s list of the 50 most influential history of the kibbutz and Socialist-Zi- for the first time in 2,000 years and Israel Studies Fall program, “Divided by Victory: Jews in the United States. onism. She was recently a recipient of took control over more land than most peo- The Legacy of the Six-Day War” will be On Thursday, November 2, Lior Lib- the Frankel Institute of Advanced Judaic ple thought possible. However, the initial held on Thursday, October 26, when Steven man, assistant professor and associate Studies faculty fellowship to work on her euphoria of the victory ultimately led to Bayme, director of the William Petschek director of the Center for Israel Studies project “Jews in Harness: The Socialist-Zi- basic divisions that have fragmented Israeli Contemporary Jewish Life Department of at Binghamton University will speak on onist Labor Movement and Hasidism.” society and Diaspora Jews over a host of the American Jewish Committee will speak “Between the Seventh Day and ‘The Move- The final lecture in the program will be on concerns, including issues of land and/or on “The Six-Day War Remembered 50 ment for Greater Israel’: The Aftermath of Thursday, November 9, when Assaf Harel peace, and occupation and/or democracy. -

Late Marriage Walk on Water Dough

FILM SERIES Place: The 519 Community Centre, Room 301 (room subject to change, please check monitor at 519 when arriving for the film screening) Time: 1:30 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. Admission is free and light snacks may be brought to the venue. LATE MARRIAGE Date: Sunday, October 21, 2018 Hatuna Meuheret) is a 2001 Israeli film directed by , מאוחרת חתונה :Hebrew) Dover Kosashvili. The film centers on Zaza (Lior Ashkenazi, in his breakthrough role), the 31-year-old child of tradition-minded Georgian Jewish immigrants who are anxiously trying to arrange a marriage for him. Unbeknownst to them, he is secretly dating a 34-year-old divorcée, Judith (Ronit Elkabetz). When his parents discover the relationship and violently intervene, Zaza must choose between his family traditions and his love. Most of the main characters are Georgian-Israeli and the dialogue is partly in the Judaeo-Georgian language and partly in Hebrew. The film was positively reviewed and was Israel’s submission for Best Foreign Language Film at the 74th Academy Awards. WALK ON WATER Date: Sunday, November 18, 2018 Eyal, an Israeli Mossad agent, is given the mission to track down and kill the very old Alfred Himmelman, an ex-Nazi officer, who might still be alive. Pretending to be a tourist guide, he befriends his grandson Axel, in Israel to visit his sister Pia. The two men set out on a tour of the country during which, Axel challenges Eyal's values. DOUGH Date: Sunday, December 16, 2018 Curmudgeonly widower Nat Dayan (Tony award-winning actor Jonathan Pryce, currently in HBO's "Game of Thrones") clings to his way of life as a Kosher bakery shop owner in London's East End.