The European Landscape Convention and the Question of Public Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planprogram Innherredsveien

Planprogram for fornying av Innherredsveien. Høringsutgave Videre prosess for Gateprosjekt Innherredsveien Side 2 Planprogram Vår referanse Vår dato Gateprosjekt Innherredsveien 406253 02.11.2018 Innhold 1 Bakgrunn, formål og rammer 3 1.1 Bakgrunn 3 1.2 Formål 3 1.3 Gjeldende politiske vedtak 3 1.4 Premisser 4 1.5 Målsetninger 5 2 Dagens situasjon og framtidig behov 6 2.1 Planområdet/berørt område 6 2.2 Gjeldende plangrunnlag 6 2.3 Bystruktur, byrom, byliv 7 2.4 Kulturmiljø/-minne 9 2.5 Gatetrær 11 2.6 Luft og støy 11 2.7 Trafikksituasjon/mobilitet 14 2.8 Tekniske forhold 20 2.9 Samlet behov og begrunnelse for tiltak i Innherredsveien 21 2.10 Prøveprosjekt miljøgate innført sommer 2017 21 3 Problemstillinger og målkonflikter 22 3.1 Framtidig reisemønster, dimensjoneringsgrunnlag 22 3.2 Prioritering av trafikantgrupper 23 3.3 Pågående planer og grensesnitt 25 3.4 Måloppnåelse skal vurderes som en del av planarbeidet 25 4 Planlagt produksjon og leveranser 26 4.1 Programmering av gater og byrom 26 4.2 Modellbasert planlegging 26 5 Prosess og medvirkning 27 5.1 Milepæler i prosessen, medvirkning og beslutningspunkt 27 6 Utredningstemaer 29 Side 3 Planprogram Vår referanse Vår dato Gateprosjekt Innherredsveien 406253 02.11.2018 1 Bakgrunn, formål og rammer 1.1 Bakgrunn Innherredsveien er et av de store gateprosjektene i Miljøpakken, sammen med Kongens gate, Olav Tryggvasons gate og Elgeseter gate. Statens vegvesen Region Midt skal på vegne av Miljøpakken utarbeide plangrunnlag for fornying av i hovedtrasé for kollektivtrafikk til og fra øst. Strekningen som inngår er Innherredsveien fra Bakke bru til Statsing. -

Områderegulering Av Øvre Rotvoll - Trafikkanalyser

OKTOBER 2017 ROTVOLL EIENDOM OMRÅDEREGULERING AV ØVRE ROTVOLL - TRAFIKKANALYSER ADRESSE COWI AS Otto Nielsens veg 12 Postboks 2564 Sentrum 7414 Trondheim TLF +47 02694 WWW cowi.no OKTOBER 2017 ROTVOLL EIENDOM OMRÅDEREGULERING AV ØVRE ROTVOLL - TRAFIKKANALYSER OPPDRAGSNR. DOKUMENTNR. A070945 1 VERSJON UTGIVELSESDATO BESKRIVELSE UTARBEIDET KONTROLLERT GODKJENT 1 30.10.2017 Rapport SHFJ MAFL OMRÅDEREGULERING AV ØVRE ROTVOLL - TRAFIKKANALYSER 5 Sammendrag Denne trafikkanalysen er utarbeidet i forbindelse med områderegulering for Øvre Rotvoll. Området reguleres for utbygging av ca. 3400 boliger, et lokalt tjenestetilbud, grøntområder og offentlig formål. Brundalsforbindelsen reguleres gjennom utbyggingsområdet fra E6 Omkjøringsvegen til FV 861 Jonsvannsveien som miljøgate i fire felt hvorav to felt er forutsatt forbeholdt kollektivtrafikk. I tillegg reguleres det et lokalvegnett i området. Nullvekstmålet for biltrafikk og Bymiljøavtalen som Trondheim kommune signerte i 2016 har vært en sentral forutsetning i planarbeidet. Planforslaget sikrer en rekke tiltak som vil bidra til oppfyllelsen av nullvekstmålet. I tillegg anbefales en del tiltak som tjener samme hensikt, men som ikke kan nedfelles i reguleringsplanen. Det foreliggende planforslaget viser et i all hovedsak godt plangrep for Øvre Rotvoll med gode løsninger for kollektiv, sykkel og gange. Planforslaget viser også hvordan trafikksystemet kan løses i mellomperioden før hele Brundalsforbindelsen kommer på plass. Planen legger til rette for at nullvekst vil kunne nås gjennom alle faser av utbyggingen. Trafikkanalysene viser et spenn i trafikkmengdene i og utenfor planområdet, avhengig av hvilke parametere som legges inn. Beregningene er beheftet med en god del usikkerhet, da utbygd situasjon er langt fram i tid, og fordi det ikke er mulig å gjengi virkeligheten helt nøyaktig ved hjelp av trafikkmodeller. -

2017 Annual Report NTNU University Library

2017 Annual Report NTNU University Library Kunnskap når det gjelder Foto: Aage Hoiem, NTNU The University Library adopted a new organizational chart in May 2017. The new organization consists of seven sections: five in Trondheim, one in Gjøvik and one in Ålesund. Work routines and collaboration between the sections have been adapted to the new NTNU over the course of 2017. With sections and campuses in several plac- es and cities, there was a need to strengthen cooperation across the different sections. At the end of 2017, the library decided to organize its academic components into eight teams designed to work across all sections. This team organization will be implemented in 2018. Photo: Lene Johansen Løkkhaug, NTNU University Library A new library director began work on 1 July and a new section manager for the Library Division in Gjøvik, Kristin Aldo, started on 1 September. As a result of the end of the 2016/2017 hiring freeze, many new employees have joined the staff in all sections during the year. 2017 has been a year in which we have collected ourselves after the merger process and time has been spent on planning and preparing for new challenges in 2018. By the end of 2017, the library had been given a clear role in publishing research results and research data. The Uni- versity Library has also had a good dialogue with other departments on issues related to university education. Rune Brandshaug, Library Director, NTNU University Library 2 Allocation of costs The library's total costs in 2017 were NOK 235 million. -

Områdeplan for Øvre Rotvoll, Offentlig Ettersyn Planbeskrivelse

Byplankontoret Planident: r20150025 Arkivsak: 14/6975 Områdeplan for Øvre Rotvoll, offentlig ettersyn Planbeskrivelse Dato for siste revisjon av planbeskrivelsen : 5.9.2018 Dato for godkjenning av bystyret : Innledning Forslag til områdeplan er utarbeidet av Rotvoll Eiendom AS. Pir II AS har vært engasjert av Rotvoll Eiendom AS for å bidra med å utarbeide områdeplanen. C- Alcea AS, Brekke & Strand Akustikk AS, Cowi AS, Multiconsult AS og Norconsult AS har vært bidragsytere til utredningene og utarbeidelsen av planforslaget. Bygningsrådet vedtok i møte 5.5.2015 å gi Rotvoll Eiendom AS ansvaret for å utarbeideområdeplanen. Eksisterende situasjon Kommuneplanens arealdel Hensikten med planen er å tilrettelegge for en utbygging av et godt og tett boområde med møteplasser, funksjonsblanding og offentlige tjenestetilbud på Øvre Rotvoll. Planen åpner for ca 93999/18 Side 2 1650 boliger, lokalt sentrum, to barnehager og idrettsanlegg, inklusiv et bydelsbasseng. Brundalsforbindelsen reguleres som del av områdeplanen. Blågrønne strukturer, kulturminner og sentrale elementer i kulturlandskapet sikres i planen. Rotvoll Eiendom AS har som mål at Øvre Rotvoll gård skal utvikles til en grønn og bærekraftig bydel som det er godt å bo i, og som tar vare på viktige landskapsverdier. Det er utfordrende støy- og luftforhold i området, på grunn av at E6 Omkjøringsvegen, Innherredsveien Rv 706 og Haakon VII’s gate (Ladeforbindelsen) omkranser deler av byggeområdet som er avsatt i KPA (område 35 og 38). Planen er utredet med mål om at hele dette utbyggingsarealet kunne være med i områdeplanen. Utredninger av luftkvaliteten har imidlertid vist at det er vanskelig å få til tilfredsstillende boliger i deler av området nå. -

Lade, Leangen Og Rotvoll Kommunedelplan

TRONDHEIM KOMMUNE LADE, LEANGEN OG ROTVOLL KOMMUNEDELPLAN HØRINGSUTKAST PLAN- OG BYGNINGSENHETEN 27. NOVEMBER 2003 Trondheim kommune Forord Dette er forslag til kommunedelplan for Lade, Leangen og Rotvoll. Planforslaget består av planbeskrivelse, plankart og bestemmelser. Planen er utarbeidet i målestokk 1:5.000 og vil være juridisk bindende i denne målestokken. Vedlagt plankart er i 1:10.000. Forslaget er utarbeidet av plan- og bygningsenheten. Arbeidet med kommunedelplanen har pågått i 4 år og mange personer ved enheten har deltatt. Et forslag til kommunedelplan for Lade-Leangen har vært på høring tidligere. Idar Støwer var da ansvarlig saksbehandler. Beslutningen om at jernbanens godsterminal likevel ikke skal flyttes til Leangen, medførte at premissene for planarbeidet ble vesentlig endret. På bakgrunn av dette, ble nye forutsetninger og prinsipper for kommunedelplanen behandlet i Bygningsrådet i mars 2003. Prinsippene har dannet grunnlag for det høringsforslaget som nå foreligger. Arbeidet med dette forslaget er utført av Jorun Gjære, Ingrid Sætherø, Kathrine Strømmen og Line Snøfugl Storvik, med sistnevnte som ansvarlig saksbehandler. Plankart og temakart er utarbeidet av Berit Myren. Plan- og bygningsenheten 27.11.2003 ENDRINGER Noe korrektur og endringer 1.12.2003 Lade, Leangen og Rotvoll – Forslag til kommunedelplan Side 1 Trondheim kommune Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Planens problemstillinger og målsettinger ...........................................................................3 1.1 Problemstillinger.............................................................................................................3 -

Hensynssoner Utvalgte Kulturmiljø

Hensynssoner utvalgte kulturmiljø Kommuneplanens arealdel 2012-2024 Vedlegg 5 Forord Nye hensynssoner for kulturmiljø og kulturlandskap er utarbeidet med bakgrunn i at formålet institusjonsområder skal tas ut av kommuneplanens arealdel og at plan- og bygningsloven fra 2009 åpner opp for å bruke hensynssoner. En kulturminneplan for Trondheim kommune er under arbeid. Å avsette hensynssoner for kulturmiljø og kulturlandskap i kommuneplanens arealdel er et viktig ledd i arbeidet med å styrke kulturminnevernet i Trondheim– som er hovedmålet for kulturminneplanen. Hensikten med hensynssoner for kulturmiljø og kulturlandskap er at den kulturhistoriske verdifulle bebyggelsen og særpregede områder skal søkes bevart. Mange av kulturminnene i hensynssonene har fredningsvedtak, er med i spesialområder for bevaring i gjeldende reguleringsplaner eller vises i ”aktsomhetskart kulturminner”. Med hensynssoner i arealplankartet med tilhørende retningslinjer, vil man raskt få oversikt over særpregede kulturmiljøer i kommunen, samt få informasjon om hvordan man skal forholde seg til eksisterende kulturminner ved planlegging av nye tiltak. 04.12.2012 Einar Aassved Hansen Marianne Langedal Kommunaldirektør Miljøsjef KOMMUNEPLANENS AREALDEL 2012-24 KULTURMILJØER I TRONDHEIM MED KULTURHISTORISK VERDI Listen nedenfor omfatter en rekke miljøer der kulturhistoriske verdier er fremherskende, og der det er grunn til stor varsomhet med hensyn til alle endringer av miljøkvalitetene. Miljøene er ordnet etter løpenummer som i prinsippet er tilfeldig valgt. Beskrivelsene er høyst kortfattede, og kun ment som stikkord som skal gi en pekepinn om hvilke historisk og antikvarisk relaterte miljøkvaliteter det i hovedsak er tale om i de enkelte områdene. Områdene er vist med skravur på arealplankartet. 1 1.1 ”Onsøyhåggan” med tilstøtende LNF-område i dalføret Velbevart og landskapsmessig særlig godt eksponert ”snitt” av Bynesets kulturlandskap, inkl. -

Midtpunkt Nr. 5

midtpunkt5/12 Citan og MacGyver! En ny størrelse. Scan nå og se nye episoder. En ny standard. Citan – vår nye storhet! Helt nye Citan gir deg Mercedes-Benz kvalitet i en mindre utgave. Med Citans driftssikkerhet og fleksibilitet er det ikke rart at de beste velger det beste. Pris fra kr 162.400,- eks. mva. Kvalitet i arbeid. Pris er eksklusiv frakt- og leveringsomkostninger. Forbruk blandet kjøring: 0,43-0,47 liter pr/mil. CO2 utslipp: 112-123 g/km. Motor-Trade AS, Sundlandsveien 2, 7032 Trondheim, tlf. 73 82 01 00. www.motortrade.no Motor-Trade AS, Russerveien 2, 7650 Verdal, tlf. 74 07 52 50, www.motortrade.no A4_Citan-Motor-Trade.indd 1 26.09.12 12.00 14 NiTs mann på Melhus 32 Madame Beyer, Marit Collin 27 Nummer to i Trondheim Innhold Leder....................................................................................................... 4 Manifestasjon 2012 ............................................................................. 22 Tema: IKT-bransje i vekst ...................................................................... 5 Vant halv million Øien-kroner .............................................................. 24 Vil synliggjøre vIKTig bransje ................................................................ 5 Rica Nidelven Hotel ble Årets Bedrift ................................................. 25 IKT er «alt» ............................................................................................. 6 Politikerintervjuet: Knut Fagerbakke (SV) ............................................ 27 Global slåsskjempe -

Prosjektmarkedet I Trondheim Utvikling Mot 2023 Og 2040

Prosjektmarkedet i Trondheim Utvikling mot 2023 og 2040 Trondheim040 Optiman skal organisere, utvikle og gjennomføre utbyggingsprosjekter på vegne av oppdragsgiver 18 ansatte, 16. driftsår Engasjert i flere utvikling-/planprosjekter Clarion Hotel & Kongress Lokk Leangen Sirkus Shopping Trondheim Sentralstasjon City Lade Tungaveien 26 Ny brannstasjonsstruktur Mulighetsstanke Sluppen «Midtbykvartalet» Etablert høsten 1997 Sentrumsområder Avlastningssenter Lade/Leangen Sentrum Avlastningssenter Tiller Trondheim – utvikling frem mot 2040 26 år tilbake 2013 27 år frem 1987 2040 «Origo» City Syd åpner 1997 2023 10 år 16 år 10 år 17 år Forende-Kvartalet Byhaven og Mercur Trondheim Torg Tillertorget KBS Nedre Elvehavn ~ferdig Valentinlystsenteret City Lade Etableringer Ivar «Brannkvartalet» ? ? Lykkes veg «Fokuskvartalet» Realfagsbygget Sparebank 1 Søndre «Trøkket mot 1000-års Lade Arena I og II jubileum og ski-VM» Sirkus Boligblokker «tar av» Clarion Brattøra • Start av Nedre City Lade tr 2 Elvehavn St. Olav • Boliger Nobø Barnehage og skolesatsing E6 øst er ferdig Bakgrunn for byggeprosjekter 1. Befolkningsvekst, som medfører: – Folk trenger hus å bo i – Jobben trenger bygninger for sin lokalisering – Servicebehov øker, gir økt behov for • Barnehager • Skoler • Sykehus • Sykehjem • Helse/pleie generelt – Handel øker – Infrastrukturer må forbedres 2. Nyetableringer 3. Rehabiliteringsbehov Befolkningsøkning 240.000 ∑+60.000 210.000 +30.000 180.000 180.000 2013 2024 2040 Tendens 2013 – 2018 ca 60-70% av boligene kommer i øst 1.200-1.400 -

Ladestien2007.Qxp 01.02.2007 21:00 Side 1

Ladestien2007.qxp 01.02.2007 21:00 Side 1 Ladestien isdekket forsvant hevet Ladejarlene Lade gård Lade kirke Bygningene har vært brukt av Norges geolo- landet seg. Havet vasket (Jarl = fornem mann, fyrste) Fra tidlig middelalder var Lade gård trøn- Lade kirke ble bygd omkring 1200. Både folk giske undersøkelser (NGU). I 2006 ble i strandkanten og området regulert og sikret som friområde. I 1984 utarbeidet Trondheim kommune Kort tid før 900 etablerer en jarleætt fra dernes sentrum og regnet som en helligdom. fra Strinda, Malvik og fra fjordens nordside flyttet mye av Bygninger skal rives og området settes i forslag til disposisjonsplan for friområ- Hålogaland seg på Lade. Lade gård blir et Her var hov (hedensk tempel) og handelssen- sognet hit. Kirken var etter grenseutvidelsen leiren ut på bun- stand. Her nede har NGU to plakater med dene ved sjøen på Lade. Et av målene politisk maktsentrum med hedensk kultus. trum. Fjorden lå på den tiden om lag seks til av Trondheim i 1952 havnet innenfor nen av dagens geologisk orientering om Trondheimsfjorden var å skape muligheter for en sti langs Den utgjør et jarleherre-dømme i Trøndelag. ti meter høyere enn i dag og Lade hadde da bygrensen, men var fremdeles soknekirke for fjord. Det slipte og grønnstein. sjøen og med det en forbindelseslinje Det heter at Harald Hårfagre lot Lade gård to havner. En ved Ladebekkens utløp og en i Lade menighet i Strinda. I 1970 ble de gamle også stein og mellom badeområdene. bygges ut som kongsgård. Sammen med en Korsvika. soknegrensene mellom gamle Strinda og blokker som lig- Opparbeidingen av stien startet i 1989 jarl slo de ut småkongene i de åtte Olav den hellige gjorde gården om til konge- Trondheim revidert. -

Cruise Excursions

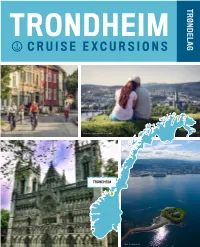

TRØNDELAG TRONDHEIM CRUISE EXCURSIONS Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com TRONDHEIM Photo: Marnie VIkan Firing Photo: Trondheim Havn TRONDHEIM TRØNDELAG THE ROYAL CAPITAL OF NORWAY THE HEART OF NORWEGIAN HISTORY Trondheim was founded by Viking King Olav Tryggvason in AD 997. A journey in Trøndelag, also known as Central-Norway, will give It was the nation’s first capital, and continues to be the historical you plenty of unforgettable stories to tell when you get back home. capital of Norway. The city is surrounded by lovely forested hills, Trøndelag is like Norway in miniature. Within few hours from Trond- and the Nidelven River winds through the city. The charming old heim, the historical capital of Norway, you can reach the coastline streets at Bakklandet bring you back to architectural traditions and with beautiful archipelagos and its coastal culture, the historical the atmosphere of days gone by. It has been, and still is, a popular cultural landscape around the Trondheim Fjord and the mountains pilgrimage site, due to the famous Nidaros Cathedral. Trondheim in the national parks where the snow never melts. Observe exotic is the 3rd largest city in Norway – vivid and lively, with everything animals like musk ox or moose in their natural environment, join a a big city can offer, but still with the friendliness of small towns. fishing trip in one of the best angler regions in the world or follow While medieval times still have their mark on the center, innovation the tracks of the Vikings. If you want to combine impressive nature and modernity shape it. -

Gå Bortover Teglbrennervn

TRONDHEIM RUNDVANDRING Løype nr. 2 Side 1 av 2 LØYPE 2 21 km START SHELL ELGESETER Løypa går nord og øst for sentrum: Øya – Sentrum – Lademoen – Ringve – Rotvoll – Leangen – Strindheim - Kuhaugen – Møllenberg – Bakklandet – Øya NB: DET ER FORTSATT MYE ANLEGGSAKTIVITET I OMRÅDET MØLLENBERG/NYHAVNA OG GRILSTAD-GILDHEIM-BROMSTAD- STRINDHEIM Asfalt og grus, barnevognvennlig HUSK Å STEMPLE STARTKORT FØR DU GÅR UT! Gå til v. ut fra stasjonen, ned mot Elgeseter bru, til v. langs elvebredden forbi Nye Spectrum (tidl. Nidarøhallen). Kryss Nidelva på siste gangbru (1). Hold til v ved Ila kirke. og kryss Kongensgt. (lysregulert), til h. forbi parken, statuen (An Magritt) og Ilevollen, over gangfelt igjen og videre rett fram Hospitalløkkan (énvegskjørt brulagt gate) og Dronningensgt. Til h. opp Munkegt, forbi Stiftsgården mot Olav Tryggvassonsstauen på Torget. Nidarosdomen rett i mot. Ta Kongensgt. til v. før Torget (2) og til v. igjen ned Nordre gt. – gågt. – ved Vår Frue kirke. Ta til h. i Olav Tryggvassonsgt. og til v. før Bakke bru (3) ned Kjøpmannsgt., retning Hotel Royal Garden. Fortsett rett fram forbi Trondhjems Sjøfartsmuseum og over Brattørbrua (gå på h. side). Gå gangbru (”Blomsterbrua”) (4) over elva, mot Nedre Elvehavn. Fortsett skrått venstre, mellom byggene, retning Rosenborg- bassenget. Fortsett under rundkjøring (gangtunnel) (5) , videre inn i Strandveiparken. Ta til v. etter lekeplass og til h. opp igjen før jernbaneundergang. Ta til v. Østersundsgt. ved bydelskaféen, forbi Lademoen barnehage, etablert 1893, ta til h. opp Biskop Sigurds gt. og til v. Mellomvegen. og gjennom parken foran Lademoen kirke. Hold rett fram, på v. side av kirk. (Lademoen skole til v.) Fortsett videre fram Lademoens kirke-allé, sperret for gjennomkjøring. -

SELBERG ARKITEKTER AS Elgeseter Gate

Elgeseter gate SELBERG ARKITEKTER AS plan I arkitektur I landskap Gruppen besto av: Anders Beitnes - Faveo Prosjektledelse AS Knut Selberg - Selberg Arkitekter AS Superbuss er viktig men mye forskjellig Delft Superbuss: Muligheter for høystandard bussløsninger i Norge Malmø Cambridge Kina Figur 3.1: Rutenettet i Trondheim (v) og med forslag til superbusslinje tegnet inn (h) 20 Copyright © Transportøkonomisk institutt, 2008 Denne publikasjonen er vernet i henhold til Åndsverkloven av 1961 Superbuss er etterspurt Skal det løses endimensjonalt etter sektor?? Skal det løses i et samlet byutviklingsgrep som løser ikke bare supebuss men mange andre problem i gaten også??? Vi velger den siste tilnærmingen - byplan Litt bakgrunn,Prioritering noen da vispørsmål var virkelig og fattig definisjoener.. Bakgrunn Elgeseter gate fungerer idag trafikkteknisk - trafikken kommer igjennom Men Bebyggelsen er svært nedslitt av trafikkbelastning og svært dårlig tilgjengelighet - miljøproblemer Kollektivtrafikken ønsker bedre framkommelighet - superbuss - politisk viktig Elgeseter gate er innfarten til midtbyen fra sør og et bindeledd til kommende nybyen på Sluppen - finnes ikke alternativ Elgeseter gate er sammensatt En av byens største boliggater Forbausende lite handel - kfr Bogstadveien Hovedinnfart til midtbyen fra syd Hovedinnfart for kollektivtransport Hovedakse for St Olav og Universitet En viktig akse for den kommende byutvikling på Lerkendal, Sorgenfri og Sluppen - viktig del av den kommende by - Byutvikling Spørsmål Skal Elgeseter gate “hoppes over” “Bindeleddet” eller skal byen være Gate sammenhengende fra “Nybyen” til “Gamlebyen”?? Er det mulig å finne løsninger og grep i Elgeseter gate uten å grave ned masse penger??? - Byggetrinn?? Miljøpakken er ikke ferdig når dagens pakke er bygget, behovet utvikles Gate med byen - gode grep tidlig sparer penger og gir kvaliteter.