Download Complete Paper in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Local Scene in Salzburg"

"Best Local Scene in Salzburg" Gecreëerd door : Cityseeker 4 Locaties in uw favorieten Old Town (Altstadt) "Old Town Salzburg" The historic nerve center of Salzburg, the Altstadt is an enchanting district that spans 236 hectares (583.16 acres). The locale's narrow cobblestone streets conceal an entire constellation of breathtaking heritage sites and architectural marvels that showcase Salsburg's vibrant past. Some of the area's prime attractions include the Salzburg Cathedral, Collegiate by Public Domain Church, Franciscan Church, Holy Trinity Church, Nonnberg Abbey, and Mozart's birthplace. +43 662 88 9870 (Tourist Information) Getreidegasse, Salzburg Getreidegasse "Salzburg's Most Famous Shopping Street" Salzburg's Getreidegasse is the most famous street in the city, therefore the most crowded. If you are really interested in getting a view of the charming old houses, try to visit early, preferably before 10 in the morning - pretty portals and wonderful courtyards can only be seen and appreciated then. The Getreidegasse is famous for its wrought-iron signs, by Edwin Lee dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries - the design of the signs dates back to the Middle Ages! It is worth taking a second look at the houses because they are adorned with dates, symbols or the names of their owners, so they often tell their own history. +43 662 8 8987 [email protected] Getreidegasse, Salzburg Residenzplatz "Central Square" Set in the center of Altstadt, Residenzplatz is a must visit when visiting the city. Dating back to the 16th Century, it was built by the then Archbishop of Salzburg, Wolf Dietrich Raitenau. -

INDIANA MAGAZINE of HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2 Hoosier Senior Naval Officers in World War I1 John B. Heffermn* Indiana furnished an exceptional number of senior of- ficers to the United States Navy in World War 11, and her sons were in the very forefront of the nation’s battles, as casualty lists and other records testify. The official sum- mary of casualties of World War I1 for the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, covering officers and men, shows for Indiana 1,467 killed or died of wounds resulting from combat, 32 others died in prison camps, 2,050 wounded, and 94 released prisoners of war. There were in the Navy from Indiana 9,412 officers (of this number, probably about 6 per- cent or 555 were officers of the Regular Navy, about 10 per- cent or 894 were temporary officers promoted from enlisted grades of the Regular Navy, and about 85 percent or 7,963 were Reserve officers) and 93,219 enlisted men, or a total of 102,631. In the Marine Corps a total of 15,360 officers and men were from Indiana, while the Coast Guard had 229 offic- ers and 3,556 enlisted men, for a total of 3,785 Hoosiers. Thus, the overall Indiana total for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard was 121,776. By way of comparison, there were about 258,870 Hoosiers in the Army.l There is nothing remarkable about the totals and Indiana’s representation in the Navy was not exceptional in quantity; but it was extraordinary in quality. -

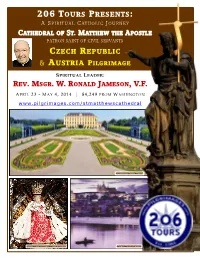

Rev. Msgr. W. Ronald Jameson, V.F

206 TOURS PRESENTS: A S PIRITUAL C ATHOLIC J OURNEY CATHEDRAL OF ST. MATTHEW THE APOSTLE PATRON SAINT OF CIVIL SERVANTS CZECH REPUBLIC & AUSTRIA PILGRIMAGE SPIRITUAL LEADER: REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. A PRIL 23 - M AY 4, 2014 | $4,249 FROM W ASHINGTON www.pilgrimages.com/stmatthewscathedral Schonbrunn Palace, Vienna Infant Jesus of Prague, Czech Republic Prague, Czech Republic Strauss Statute in Stadt Park, Vienna St. Charles Church, Vienna ABOUT REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. Msgr. Jameson was raised in Hughesville, MD and studied at St. Charles College High School, St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore and the Theological College of the Catholic University of America. Msgr. Jameson was eventually ordained in 1968. Following his ordination, he completed two assignments in Maryland parishes, followed by an assign- ment for St. Matthew's Cathedral (1974- 1985). Msgr. Jameson has served God in many ways. He has achieved many titles, assumed positions for a variety of archdiocesan posi- tions and served or serves on multiple na- tional boards. In October 2007, Theological College bestowed on Msgr. Jameson its Alumnus Lifetime Service Award honoring him as Pastor-Leader of the Faith Communi- ty due to his many archdiocesan positions and his outstanding service to God. His legacy to St. Matthew's Cathedral will undoubtedly be his enduring interest in building parish community, establishing a parish archive and history project, orches- trating the Cathedral's major restoration project and the construction of the adjoining rectory and office building project on Rhode Island Avenue (1998-2006). *NOTE: The "V.F." after Msgr Jameson's name denotes that he is appointed by the Archbishop as a Vicar Forane or Dean of one of the ecclesial subdivisions (i.e. -

Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart's View of the World

Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World by Thomas McPharlin Ford B. Arts (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy European Studies – School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide July 2010 i Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World. Preface vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Leopold Mozart, 1719–1756: The Making of an Enlightened Father 10 1.1: Leopold’s education. 11 1.2: Leopold’s model of education. 17 1.3: Leopold, Gellert, Gottsched and Günther. 24 1.4: Leopold and his Versuch. 32 Chapter 2: The Mozarts’ Taste: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s aesthetic perception of their world. 39 2.1: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s general aesthetic outlook. 40 2.2: Leopold and the aesthetics in his Versuch. 49 2.3: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s musical aesthetics. 53 2.4: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s opera aesthetics. 56 Chapter 3: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1756–1778: The education of a Wunderkind. 64 3.1: The Grand Tour. 65 3.2: Tour of Vienna. 82 3.3: Tour of Italy. 89 3.4: Leopold and Wolfgang on Wieland. 96 Chapter 4: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1778–1781: Sturm und Drang and the demise of the Mozarts’ relationship. 106 4.1: Wolfgang’s Paris journey without Leopold. 110 4.2: Maria Anna Mozart’s death. 122 4.3: Wolfgang’s relations with the Weber family. 129 4.4: Wolfgang’s break with Salzburg patronage. -

Salzb., the Last Day of Sept. Mon Trés Cher Fils!1 1777 This Morning There

0340. LEOPOLD MOZART TO HIS SON, MUNICH Salzb., the last day of Sept. Mon trés cher Fils!1 1777 This morning there was a rehearsal in the theatre, Haydn2 had to write the intermezzos between the acts for Zayre.3As early as 9 o’clock, they were coming in one after another, [5] after 10 o’clock it started, and it was not finished until towards half past 11. Of course, there was always Turkish music4 amongst it, then also a march. Countess von Schönborn5 also came to the rehearsal, driven in a chaise by Count Czernin.6 The music is said to fit the action very well and to be good. Now, although there was nothing but instrumental music, the court clavier had to be brought over, [10] for Haydn played. The previous day, Hafeneder’s music for the end of the university year was performed by night7 in the Noble Pages’ garden8 at the back, where Rosa9 lived. The Prince10 dined at Hellbrunn,11 and the play started after half past 6. Herr von Mayregg12 stood at the door as commissioner, and the 2 valets Bauernfeind and Aigner collected the tickets, the nobility had [15] no tickets, and yet 600 had been given out. We saw the throng from the window, but it was not as great as I had imagined, for almost half the tickets were not used. They say it is to be performed quite frequently, and then I can hear the music if I want. I saw the main stage rehearsal. The play was already finished at half past 8; consequently, the Prince [20] and everyone had to wait half an hour for their coaches. -

European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play

14 DAYS BIRKDALE & MANLY PARISH European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play 11 Nights / 14 Days Fri 24 July - Thu 6 Aug, 2020 • Bologna (2) • Ravenna • Padua (2) • Venice • Ljubljana (2) • Lake Bled • Salzburg (3) • Innsbruck • Oberammergau Passion Play (2) Accompanied by: Fr Frank Jones Church of the Assumption - Bled Island, Slovenia Triple Bridge, Slovenia St Anthony Basilica, Padua Italy Mondsee, Austria Meal Code DAY 5: TUESDAY 28 JULY – VENICE & PADUA (BD) DAY 8: FRIDAY 31 JULY – VIA LAKE BLED TO (B) = Breakfast (L) = Lunch (D) = Dinner Venice comprises a dense network of waterways SALZBURG (BD) with 117 islands and more than 400 bridges over Departing Ljubljana this morning we travel DAY 1: FRIDAY 24 JULY - DEPART FOR its 150 canals. Instead of main streets, you’ll find through rural Slovenia towards the Julian Alps EUROPE main canals, instead of cars, you’ll find Gondolas! to Bled. Upon arrival we take a short boat ride to Bled Island (weather permitting), where we DAY 2: SATURDAY 25 JULY - ARRIVE Today we travel out to Venice, known as visit the Church of the Assumption. BOLOGNA (D) Europe’s most romantic destination. As we Today we arrive into Bologna. This is one board our boat transfer we enjoy our first Returning to the mainland, we visit the of Italy’s most ancient cities and is home to glimpses of this unique city. Our time here medieval Bled Castle perched on a cliff high above the lake, offering splendid views of the its oldest university. The Dominicans were begins with Mass in St Mark’s Basilica, built surrounding Alpine peaks and lake below. -

Magnificent Journeys

Magnificent Journeys Taking Pilgrims to Holy Places TM Join us for our 20th Anniversary Pilgrimage SPRING 2020 VOL. 13 inRiver South France with excursions Cruise to Paris and Lourdes FLORENCE ROME MONTRÉAL JERUSALEM Founder’s Letter Dear Pilgrim Family, nother amazing year has Acome to an end. It is crazy to think that the second decade of the third millennium has come to completion. As I reflect on the many blessings of the past year, I am reminded of Luke 17:11-19. In this passage Jesus healed 10 lepers, and only one, the Samari- tan, comes back to thank Jesus. We should never be one of the nine who failed to ex- press gratitude. My husband, Ray, and I are so thankful for the many blessings and mir- acles with which God continues to grace our family, Magnificat Travel, and you, our pilgrimage family. A pilgrim who traveled to France with Immaculate Conception Church in Den- ham Springs, Louisiana, wrote to us saying, “Words cannot adequately express what this pilgrimage meant to my husband and me. We learned so much about the saints and realized what great examples of faith they are to us. The sites were beautiful and The Tregre Family gathers for the holidays (from top left): Andrew Tregre, Matthew Tregre, Evelyn the experience wonderful.” Tregre, Brandon Marin and Mike Templet. Front row: Alexis Tregre, Caroline Tregre, Ray Tregre, In 2019, we partnered with 44 Spiri- Amelia Tregre, Maria Tregre, Katie Templet and Charlotte Templet. tual Directors and Leaders as we coordi- nated and led 34 pilgrimages and missions around the world. -

Religion and the Return of Magic: Wicca As Esoteric Spirituality

RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD March 2000 Joanne Elizabeth Pearson, B.A. (Hons.) ProQuest Number: 11003543 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003543 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION The thesis presented is entirely my own work, and has not been previously presented for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. The views expressed here are those of the author and not of Lancaster University. Joanne Elizabeth Pearson. RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY CONTENTS DIAGRAMS AND ILLUSTRATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi INTRODUCTION: RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC 1 CATEGORISING WICCA 1 The Sociology of the Occult 3 The New Age Movement 5 New Religious Movements and ‘Revived’ Religion 6 Nature Religion 8 MAGIC AND RELIGION 9 A Brief Outline of the Debate 9 Religion and the Decline o f Magic? 12 ESOTERICISM 16 Academic Understandings of -

Is Belief in the Supernatural Inevitable?

Will humankind always be religious? Will ancient views of God and the cosmos disintegrate as more and more people employ the scientific method for understanding the world? Or is there something within the human breast that can never let go of beliefs in supernatural reality? The following three essays—by William Sims Bainbridge, Albert Ellis, and Ronald O. Clarke paint a fascinating picture of the psychological foundations of religious belief a picture as disturbing as it is illuminating. Is Belief in the Supernatural Inevitable? William Sims Bainbridge n a pair of books, The Future of Religion and A Theory you, let me invite you to ask a set of three simple questions. In of Religion, Rodney Stark and I have tried to demonstrate return, I will offer you evidence and explanations that Stark that religion is the inevitable human response to the condi- and I have gathered. If you find them insufficient as answers, tions of life. Hemmed by drastic limitations to our desires and then you will be left to struggle with three very serious ques- faced with the ultimate loss of everything we hold dear, humans tions: have no choice but to postulate beings and forces that exist 1. Why have humans traditionally possessed religion? beyond the natural world and to seek their aid. A Theory of 2. What is the condition of religion in America today? Religion deduces the necessity of religion from a few, simple 3. How viable are the alternatives to religion? propositions about humans and the world we inhabit, while The Future of Religion offers empirical data to support our Why have humans traditionally possessed religion? theoretical analysis. -

OCTOBER, 2006 St. Mark's Pro-Cathedral Hastings, Nebraska

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER, 2006 St. Mark’s Pro-Cathedral Hastings, Nebraska Cover feature on pages 31–32 ica and Great Britain. The festival will Matthew Lewis; 10/22, Thomas Spacht; use two of the most significant instru- 10/29, Justin Hartz; November 5, Rut- THE DIAPASON ments in London for its Exhibition- gers Collegium Musicum; 11/12, Mark A Scranton Gillette Publication Concerts: the original 1883 “Father” Pacoe; 11/19, David Schelat; 11/26, Ninety-seventh Year: No. 10, Whole No. 1163 OCTOBER, 2006 Willis organ in St. Dominic’s Priory organ students of the Mason Gross Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 (Haverstock Hill) and the newly School of the Arts, Rutgers; December restored 1963 Walker organ in St. John 10, Vox Fidelis; December 17, Advent An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, the Evangelist (Islington). Lessons & Carols. For information: the Harpsichord, the Carillon and Church Music The first two Exhibition-Concerts in <christchurchnewbrunswick.org>. London take place on October 7 and 14, and both are preceded by pubic discus- St. James Episcopal Cathedral, sions on organ composition today. Addi- Chicago, Illinois, continues its music CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] tionally, there are three ‘new music’ series: October 14, Mozart chamber 847/391-1045 concerts at Westminster Abbey, West- music; 10/15, The Cathedral Choir, FEATURES minster Cathedral and St. Dominic’s soloists, and chamber orchestra; Introducing Charles Quef Priory. Full details can be found on the November 5, Choral Evensong; 11/19, Forgotten master of La Trinité in Paris Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON festival website <www.afnom.org>. -

Summer 2018 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 71 Article 1 Number 3 Summer 2018 2018 Summer 2018 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2018) "Summer 2018 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 71 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Summer 2018 Full Issue Summer 2018 Volume 71, Number 3 Summer 2018 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2018 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 71 [2018], No. 3, Art. 1 Cover The Navy’s unmanned X-47B flies near the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roo- sevelt (CVN 71) in the Atlantic Ocean in August 2014. The aircraft completed a series of tests demonstrating its ability to operate safely and seamlessly with manned aircraft. In “Lifting the Fog of Targeting: ‘Autonomous Weapons’ and Human Control through the Lens of Military Targeting,” Merel A. C. Ekelhof addresses the current context of increas- ingly autonomous weapons, making the case that military targeting practices should be the core of any analysis that seeks a better understanding of the concept of meaningful human control. -

II. Die Amerikanische Deutschlandkonzeption Und -Politik 1918-1919

202 II. Die amerikanische Deutschlandkonzeption und -politik 1918-1919 10. Amerikanische Friedensziele. Neue Weltordnung und globale Sicherheit 10. 1. Kollektive Sicherheit statt Kräftegleichgewicht. Präsident Wilson und die amerikanischen Friedensziele in der Phase der Neutralität Die Vereinigten Staaten traten am 6. April 1917 unter Präsident Thomas Woodrow Wilson in den Ersten Weltkrieg ein. Wilson, bis 1910 Professor und Präsident der Princeton-Universität, danach Gouverneur im Staat New Jersey, war 1912 als demokra- tischer Kandidat zum US-Präsidenten gewählt worden.1 Rhetorisch hochbegabt, legte er während des Krieges mit Idealismus und Sendungsbewußtsein die Grundlagen für eine führende Rolle der USA in der Weltpolitik, schuf die politische und ideologische Vor- aussetzung für das "amerikanische Jahrhundert".2 In seinen Reden der Jahre 1916 und 1917 und in den sogenannten Fourteen Points, Four Principles und Five Particulars des Jahres 1918 entwarf Wilson sein Friedensziel einer freiheitlichen Friedensordnung glo- baler Reichweite. Wilsons Friedensplan bildete formal und inhaltlich die Grundlage und den Maßstab für die Anrufung der USA durch die deutsche Regierung am 3. Oktober 1918, mit Abstri- chen auch für die Friedensziele der Ententemächte sowie schließlich für die letzte Note der US-Regierung an Deutschland vom 5. November 1918. Diese nach dem amerikani- schen Außenminister benannte Lansing-Note, häufig als Vorwaffenstillstandsabkom- men ("pre-Armistice-agreement") bezeichnet, bahnte den Weg zum Waffenstillstand am 11. November