KINGDOM of CAMBODIA Nation Religion King ECOSYSTEM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Genomics of the Balsaminaceae Sister Genera Hydrocera Triflora and Impatiens Pinfanensis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Comparative Genomics of the Balsaminaceae Sister Genera Hydrocera triflora and Impatiens pinfanensis Zhi-Zhong Li 1,2,†, Josphat K. Saina 1,2,3,†, Andrew W. Gichira 1,2,3, Cornelius M. Kyalo 1,2,3, Qing-Feng Wang 1,3,* and Jin-Ming Chen 1,3,* ID 1 Key Laboratory of Aquatic Botany and Watershed Ecology, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] (Z.-Z.L.); [email protected] (J.K.S.); [email protected] (A.W.G.); [email protected] (C.M.K.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Sino-African Joint Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.-F.W.); [email protected] (J.-M.C.); Tel.: +86-27-8751-0526 (Q.-F.W.); +86-27-8761-7212 (J.-M.C.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 21 December 2017; Accepted: 15 January 2018; Published: 22 January 2018 Abstract: The family Balsaminaceae, which consists of the economically important genus Impatiens and the monotypic genus Hydrocera, lacks a reported or published complete chloroplast genome sequence. Therefore, chloroplast genome sequences of the two sister genera are significant to give insight into the phylogenetic position and understanding the evolution of the Balsaminaceae family among the Ericales. In this study, complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of Impatiens pinfanensis and Hydrocera triflora were characterized and assembled using a high-throughput sequencing method. The complete cp genomes were found to possess the typical quadripartite structure of land plants chloroplast genomes with double-stranded molecules of 154,189 bp (Impatiens pinfanensis) and 152,238 bp (Hydrocera triflora) in length. -

The Stationary Trawl (Dai) Fishery of the Tonle Sap-Great Lake System, Cambodia

ISSN: 1683-1489 Mekong River Commission The Stationary Trawl (Dai) Fishery of the Tonle Sap-Great Lake System, Cambodia MRC Technical Paper No. 32 August 2013 . Cambodia Lao PDR Thailand Viet Nam Page 1 For sustainable development Cambodia . Lao PDR . Thailand . Viet Nam For sustainable development Mekong River Commission The Stationary Trawl (Dai) Fishery of the Tonle Sap-Great Lake System, Cambodia MRC Technical Paper No. 32 August 2013 Cambodia . Lao PDR . Thailand . Viet Nam For sustainable development Published in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in August 2013 by the Mekong River Commission Cite this document as: Halls, A.S.; Paxton, B.R.; Hall, N.; Peng Bun, N.; Lieng, S.; Pengby, N.; and So, N (2013). The Stationary Trawl (Dai) Fishery of the Tonle Sap-Great Lake, Cambodia. MRC Technical Paper No. 32, Mekong River Commission, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 142pp. ISSN: 1683-1489. The opinions and interpretations expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mekong River Commission. Cover Photo: J. Garrison Editors: K.G. Hortle, T. Hacker, T.R. Meadley and P. Degen Graphic design and layout: C. Chhut Office of the Secretariat in Phnom Penh (OSP) Office of the Secretariat in Vientiane (OSV) 576 National Road, #2, Chak Angre Krom, Office of the Chief Executive Officer P.O. Box 623, 184 Fa Ngoum Road, P.O. Box 6101, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Vientiane, Lao PDR Tel. (855-23) 425 353 Tel. (856-21) 263 263 Fax. (855-23) 425 363 Fax. (856-21) 263 264 © Mekong River Commission E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.mrcmekong.org Table of contents List of tables ... -

Prek Toal Core Area Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve

Prek Toal Core Area Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve Management Plan 2007-2011 PLAN PREPARED BY THE TONLE SAP CONSERVATION PROJECT IN ASSOCIATION WITH MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES Foreword As defined by UNESCO, Biosphere Reserves are "areas of terrestrial and coastal/marine ecosystems, or a combination thereof, which are internationally recognized within the framework of UNESCO's Programme on Man and the Biosphere (Statutory Framework of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves). Reserves are nominated by national governments; each must meet a minimal set of criteria and adhere to a minimal set of conditions before being admitted to the network. Each Biosphere Reserve is intended to fulfil three complementary functions: 1) a conservation function, to preserve genetic resources, species, ecosystems and landscapes; 2) a development function, to foster sustainable economic and human development; and, 3) a logistic support function, to support demonstration projects, environmental education and training, and research and monitoring related to local, national and global issues of conservation and sustainable development. Physically, each Biosphere Reserve comprises three elements: one or more core areas, which are securely Foreword protected sites for conserving biological diversity, monitoring minimally disturbed ecosystems, and undertaking non-destructive research and other low-impact uses (such as education); a clearly identified buffer zone, which usually surrounds or adjoins the core areas, and is used for cooperative activities compatible with sound ecological practices, including environmental education, recreation, ecotourism and applied and basic research; and a flexible transition zone, or area of cooperation, which may contain a variety of agricultural activities, settlements and other uses, and in which local communities, management agencies, scientists, non-governmental organizations, cultural groups, economic interests and other stakeholders work together to manage and sustainably develop the area's resources. -

Status of the Flooded Forest in Fishing Lot #2, Battambang Province

Status of the Flooded Forest in Fishing Lot #2, Battambang Province by Troeung Rot Fishery Officer and Counterpart of MRC/DoF/Danida Fisheries Program in Cambodia of Battambang Province ABSTRACT The flooded (seasonally inundated) forest provides many important benefits for people and animals. People use forest resources for firewood and household materials, and the forest habitats are important for fish and other wildlife populations. However, although the law prohibits such activities, fisheries and farming communities are clearing the forest for development purposes. According to figures produced by the Battambang Provincial Fisheries Office in 1992, nearly 30% of the flooded forest has been cleared since 1972. Of the 12 fishing lots in Battambang province, Fishing Lot #2 has been most affected. With an area of 50,600 ha Lot #2 offers great potential as wildlife habitat, but 10,688 ha of the forest in this lot has already been cleared. This paper describes the flooded forest in Fishing Lot #2, the main threats to the forest, its location and importance, the resource users, and the relationship between the flooded forest and the fishes and other animals that inhabit it. 1. INTRODUCTION The flooded (seasonally inundated) forest not only provides favorable habitats for many animals but also provides local people with firewood, household materials etc. However the flooded forest is declining in extent as large areas are being destroyed by fishers and farmers. One of the areas in Cambodia where a large area of flooded forest remains is in Battambang province. In 1992 the Battambang Provincial Fisheries Office (PFO) discovered that 32,463 ha (almost 30%) of the flooded forest had been cleared since 1965 (see Table 6.1). -

Forest Habitats and Flora in Laos PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259623025 Forest Habitats and Flora in Laos PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam Conference Paper · January 1999 CITATIONS READS 12 517 1 author: Philip W. Rundel University of California, Los Angeles 283 PUBLICATIONS 8,872 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Philip W. Rundel Retrieved on: 03 October 2016 Rundel 1999 …Forest Habitats and Flora in Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Vietnam 1 Conservation Priorities In Indochina - WWF Desk Study FOREST HABITATS AND FLORA IN LAO PDR, CAMBODIA, AND VIETNAM Philip W. Rundel, PhD Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of California Los Angeles, California USA 90095 December 1999 Prepared for World Wide Fund for Nature, Indochina Programme Office, Hanoi Rundel 1999 …Forest Habitats and Flora in Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Vietnam 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Geomorphology of Southeast Asia 1.1 Geologic History 1.2 Geomorphic Provinces 1.3 Mekong River System 2. Vegetation Patterns in Southeast Asia 2.1 Regional Forest Formations 2.2 Lowland Forest Habitats 2.3 Montane Forest Habitats 2.4 Freshwater Swamp Forests 2.5 Mangrove Forests Lao People's Democratic Republic 1. Physical Geography 2. Climatic Patterns 3. Vegetation Mapping 4. Forest Habitats 5.1 Lowland Forest habitats 5.2 Montane Forest Habitats 5.3 Subtropical Broadleaf Evergreen Forest 5.4 Azonal Habitats Cambodia 1. Physical Geography 2. Hydrology 3. Climatic Patterns 4. Flora 5. Vegetation Mapping 6. Forest Habitats 5.1 Lowland Forest habitats 5.2 Montane Forest Habitats 5.3 Azonal Habitats Vietnam 1. Physical Geography 2. -

NATURAL RESOURCE USE and LIVELIHOOD TRENDS in the TONLE SAP FLOODPLAIN, CAMBODIA a Socio-Economic Analysis of Direct Use Values

Page 1 of 55 IMPERIAL COLLEGE OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE Faculty of the Life Sciences (University of London) Department of Environmental Science & Technology NATURAL RESOURCE USE AND LIVELIHOOD TRENDS IN THE TONLE SAP FLOODPLAIN, CAMBODIA A Socio-Economic Analysis of Direct Use Values in Peam Ta Our Floating Village By Gaëla Roudy A report submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the MSc in Environmental Technology. September 2002 Contact Details Gaëla Roudy, 81A, Ancien Chemin de la Lanterne, 06200, Nice, FRANCE. Tel: (+) 77 8687 2671 Email: [email protected] Declaration of Own Work I declare that this thesis: Natural Resource Use and Livelihood Trends in the Tonle Sap Floodplain, Cambodia: A Socio-Economic Analysis of Direct Use Values in Peam Ta Our Floating Village. Is entirely my own work and that where any material could be construed as the work of other, it is fully cited and referenced, and/or with appropriate acknowledgment given. Signature: Name of student: Gaëla Roudy . Name of supervisor: Dr. Jaboury Ghazoul . ABSTRACT The Tonle Sap Floodplain of Cambodia is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world. The contribution of its fisheries to the national economy and to food security is extensive. The ecosystem services and consumable goods it provides are vital for local users. Wild flora, production and construction inputs, and wildlife are used throughout the year by local populations and contribute to the economy of thousands of households around the floodplain. Although the value to local livelihoods of floodplain resources is acknowledged in the institutional literature, it remains largely unquantified Page 2 of 55 however. -

Tree Types of the World Map

Abarema abbottii-Abarema acreana-Abarema adenophora-Abarema alexandri-Abarema asplenifolia-Abarema auriculata-Abarema barbouriana-Abarema barnebyana-Abarema brachystachya-Abarema callejasii-Abarema campestris-Abarema centiflora-Abarema cochleata-Abarema cochliocarpos-Abarema commutata-Abarema curvicarpa-Abarema ferruginea-Abarema filamentosa-Abarema floribunda-Abarema gallorum-Abarema ganymedea-Abarema glauca-Abarema idiopoda-Abarema josephi-Abarema jupunba-Abarema killipii-Abarema laeta-Abarema langsdorffii-Abarema lehmannii-Abarema leucophylla-Abarema levelii-Abarema limae-Abarema longipedunculata-Abarema macradenia-Abarema maestrensis-Abarema mataybifolia-Abarema microcalyx-Abarema nipensis-Abarema obovalis-Abarema obovata-Abarema oppositifolia-Abarema oxyphyllidia-Abarema piresii-Abarema racemiflora-Abarema turbinata-Abarema villifera-Abarema villosa-Abarema zolleriana-Abatia mexicana-Abatia parviflora-Abatia rugosa-Abatia spicata-Abelia corymbosa-Abeliophyllum distichum-Abies alba-Abies amabilis-Abies balsamea-Abies beshanzuensis-Abies bracteata-Abies cephalonica-Abies chensiensis-Abies cilicica-Abies concolor-Abies delavayi-Abies densa-Abies durangensis-Abies fabri-Abies fanjingshanensis-Abies fargesii-Abies firma-Abies forrestii-Abies fraseri-Abies grandis-Abies guatemalensis-Abies hickelii-Abies hidalgensis-Abies holophylla-Abies homolepis-Abies jaliscana-Abies kawakamii-Abies koreana-Abies lasiocarpa-Abies magnifica-Abies mariesii-Abies nebrodensis-Abies nephrolepis-Abies nordmanniana-Abies numidica-Abies pindrow-Abies pinsapo-Abies -

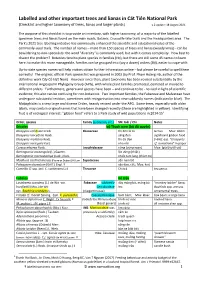

Labelled and Other Important Trees and Lianas in Cát Tiên National Park (Checklist and Higher Taxonomy of Trees, Lianas and Larger Plants) V.2 Update: 18 August 2021

Labelled and other important trees and lianas in Cát Tiên National Park (Checklist and higher taxonomy of trees, lianas and larger plants) v.2 update: 18 August 2021 The purpose of this checklist is to provide an inventory, with higher taxonomy, of a majority of the labelled specimen trees and lianas found on the main roads, Botanic, Crocodile-lake trails and the Headquarters area. The Park's 2021 tree labelling initiative has enormously enhanced the scientific and educational value of the commonly-used trails. The number of names – more than 150 species of trees and lianas (woody vines) - can be bewildering to non-specialists: the word "diversity" is commonly used, but with it comes complexity. How best to dissect the problem? Botanists tend to place species in families (Họ), but there are still some 45 names to learn here; to make this more manageable, families can be grouped into (say a dozen) orders (Bộ), easier to cope-with. Up-to-date species names will help visitors obtain further information online – but please be careful to spell them correctly! The original, official Park species list was prepared in 2002 (by Prof. Phạm Hoàng Hộ, author of the definitive work Cây Cỏ Việt Nam). However since then, plant taxonomy has been revised substantially by the international Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), with whole plant families promoted, demoted or moved to different orders. Furthermore, genera and species have been – and continue to be - revised in light of scientific evidence; this also can be confusing for non-botanists. Two important families, the Fabaceae and Malvaceae have undergone substantial revision, sometimes with reorganisation into new subfamily names (indicated in blue). -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History 2017 (2) 137–139 © Centre for Biodiversity Conservation, Phnom Penh 138 Editorial

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Northern yellow-cheeked crested gibbons Impacts on the Tonle Sap fl ooded forests Assessment of rodent communities New elephant and snake records The future for Cambodian tigers Green peafowl populations December 2017 Vol. 2017 No. 2 Cambodian Journal of Natural History Editors Email: [email protected], [email protected] • Dr Neil M. Furey, Chief Editor, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International, UK. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Mekong Case Study Manager, Conservation International, Cambodia. • Dr Ith Saveng, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. International Editorial Board • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, • Dr Sovanmoly Hul, Muséum National d’Histoire UK. Naturelle, France. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx – The International • Dr Andy L. Maxwell, World Wide Fund for Nature, Journal of Conservation, UK. Cambodia. • Dr L. Lee Grismer, La Sierra University, California, • Dr Brad Pett itt , Murdoch University, Australia. USA. • Dr Campbell O. Webb, Harvard University Herbaria, • Dr Knud E. Heller, Nykøbing Falster Zoo, Denmark. USA. Other peer reviewers • Dr Mauricio Arias, University of South Florida, USA. • Matt hew Maltby, Winrock International, USA. • Dr Paul Bates, Harrison Institute, UK. • Dr Serge Morand, Centre National de Recherche • Dr Jackson Frechett e, Fauna & Flora International, Scientifi que and Centre de Coopération Internationale en Cambodia. Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement, France. • Dr Peter Geissler, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde • Dr Tommaso Savini, King Mongkut’s University of Stutt gart, Germany. Technology Thonburi, Thailand. • Alvaro Gonzalez-Monge, Australia National • Dr Bryan Stuart, North Carolina Museum of Natural University, Australia. -

Ranunculales Dumortier (1829) Menispermaceae A

Peripheral Eudicots 122 Eudicots - Eudicotyledon (Zweikeimblättrige) Peripheral Eudicots - Periphere Eudicotyledonen Order: Ranunculales Dumortier (1829) Menispermaceae A. Jussieu, Gen. Pl. 284. 1789; nom. cons. Key to the genera: 1a. Main basal veins and their outer branches leading directly to margin ………..2 1b. Main basal vein and their outer branches are not leading to margin .……….. 3 2a. Sepals 6 in 2 whorls ……………………………………… Tinospora 2b. Sepals 8–12 in 3 or 4 whorls ................................................. Pericampylus 3a. Flowers and fruits in pedunculate umbel-like cymes or discoid heads, these often in compound umbels, sometimes forming a terminal thyrse …...................… Stephania 3b. Flowers and fruits in a simple cymes, these flat-topped or in elongated thyrses, sometimes racemelike ………………………........................................... Cissampelos CISSAMPELOS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 1031. 1753. Cissampelos pareira Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1031. 1753; H. Kanai in Hara, Fl. E. Himal. 1: 94. 1966; Grierson in Grierson et Long, Fl. Bhut. 1(2): 336. 1984; Prain, Beng. Pl. 1: 208. 1903.Cissampelos argentea Kunth, Nov. Gen. Sp. 5: 67. 1821. Cissampelos pareira Linnaeus var. hirsuta (Buchanan– Hamilton ex de Candolle) Forman, Kew Bull. 22: 356. 1968. Woody vines. Branches slender, striate, usually densely pubescent. Petioles shorter than lamina; leaf blade cordate-rotunded to rotunded, 2 – 7 cm long and wide, papery, abaxially densely pubescent, adaxially sparsely pubescent, base often cordate, sometimes subtruncate, rarely slightly rounded, apex often emarginate, with a mucronate acumen, palmately 5 – 7 veined. Male inflorescences axillary, solitary or few fascicled, corymbose cymes, pubescent. Female inflorescences thyrsoid, narrow, up to 18 cm, usually less than 10 cm; bracts foliaceous and suborbicular, overlapping along rachis, densely pubescent. -

Guide to Inundated Tree Planting: Practical Experience

Guide to Inundated Tree Planting: Practical Experience Table of Contents Acknowledgement .......................................................................................................................... i Citation ........................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Re-planting the flooded forest ...................................................................................................... 2 Site selection ................................................................................................................................. 2 Nursery .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Species selection and seed collection ............................................................................................ 3 Nursery site selection..................................................................................................................... 5 Nursery preparation and seed processing ..................................................................................... 5 Seedling protection and care ......................................................................................................... 8 Tree planting ................................................................................................................................ -

Impacts on the Tonle Sap Ecosystem

Mekong River Commission Basin Development Plan Programme, Phase 2 Assessment of basin-wide development scenarios Technical Note 10 Impacts on the Tonle Sap Ecosystem (For discussion) June 2010 Mekong River Commission Basin Development Plan Programme, Phase 2 Assessment of Basin-wide Development Scenarios Supporting Technical Notes This technical note is one of a series of technical notes prepared by the BDP assessment team to support and guide the assessment process and to facilitate informed discussion amongst stakeholders. Volume Contents Volume 1 Final Report Assessment of Basin-wide Development Scenarios Volume 2 Technical Note 1 Scoping and Planning of the Assessment Assessment Approach of Development Scenarios and Methodology Technical Note 2 Assessment Methodologies Volume 3 Technical Note 3 Assessment of Flow Changes Hydrological Impacts Technical Note 4 Impacts on River Morphology Technical Note 5 Impacts on Water Quality Volume 4 Technical Note 6 Power Benefits Power Benefits and Technical Note 7 Agricultural Impacts Agricultural Impacts Technical Note 8 Impacts of Changes in Salinity Intrusion Volume 5 Technical Note 9 Impacts on Wetlands and Biodiversity Environmental Impacts Technical Note 10 Impacts on the Tonle Sap Ecosystem Volume 6 Technical Note 11 Impacts on Fisheries Social and Economic Technical Note 12 Social Impacts Impacts Technical Note 13 Economic Benefits and Costs 2 Impacts on valuable ecosystems/habitats: 12/07/2010 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................