J.K. Mertz's Bardenklänge: a Context for the Emergence of the Character

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Simon Powis, Guitar (Australia) New Opportunities for a Twenty-First Century Guitarist 6:00 - 7:15 P.M

The 16th Annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival June 3 - 5, 2016 Vieaux, USA SoloDuo, Italy Poláčková, Czech Republic Gallén, Spain De Jonge, Canada North, England Powis, Australia Davin, USA Beattie, Canada Presented by UITARS NTERNATIONAL G I in cooperation with the GUITARSINT.COM CLEVELAND, OHIO USA 216-752-7502 Grey Fannel HAUTE COUTURE Fait Main en France • Hand Made in France www.bamcases.com Welcome Welcome to the sixteenth annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival. In pre- senting this event it has been my honor to work closely with Jason Vieaux, 2015 Grammy Award Winner and Cleveland Institute of Music Guitar Department Head; Colin Davin, recently appointed to the Cleveland Institute of Music’s Conservatory Guitar Faculty; and Tom Poore, a highly devoted guitar teacher and superb writer. Our reasons for presenting this Festival are fivefold: (1) to help increase the awareness and respect due artists whose exemplary work has enhanced our lives and the lives of others; (2) to entertain; (3) to educate; (4) to encourage deeper thought and discussion about how we listen to, perform, and evaluate fine music; and, most important, (5) to help facilitate heightened moments of human awareness. In our experience participation in the live performance of fine music is potentially one of the highest social ends towards which we can aspire as performers, music students, and audience members. For it is in live, heightened moments of musical magic—when time stops and egos dissolve—that often we are made most conscious of our shared humanity. Armin Kelly, Founder and Artistic Director Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival Acknowledgements We wish to thank the following for their generous support of this event: The Cleveland Institute of Music: Gary Hanson, Interim President; Lori Wright, Director, Concerts and Events; Marjorie Gold, Concert Production Manager; Gina Rendall, Concert Facilities Coordinator; Susan Iler, Director of Marketing and Communications; Lynn M. -

The Solo Classical Guitar Concerto

The solo classical guitar concerto: A soloist’s preparatory guide to selected works by Josina Nina Fourie-Gouws © University of Pretoria The solo classical guitar concerto: A soloist’s preparatory guide to selected works by Josina Nina Fourie-Gouws A mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music (Performing Art) Department of Music Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Professor Wessel van Wyk Co-supervisor: Abri Jordaan September 2017 © University of Pretoria ABSTRACT The study addresses the preparatory information needs of potential performers of solo classical guitar concerti. Identifying a range of specific decisions that play an important part in the pre-performance planning of an anticipated concerto performance provides performance considerations for each selected concerto. The content of six solo classical guitar concerti spanning almost 180 years by six composers from four countries was analysed for the purpose of this study. Two early guitar concerti by guitarist composers Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) and Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841), two modern concerti by non-guitarist composers Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) and Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999) and two modern concerti by guitarist composers Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) and Leo Brouwer (b.1939) were investigated. The study examines specific compositional and performance aspects of each concerto to serve as a guideline for professional performers, students and teachers. Each concerto was analysed according to similar themes: the historical significance of the investigated concerti, pre-performance considerations, the level of difficulty of selected concerti, technical observations, performance recommendations and observations regarding balance between the soloist and orchestra. -

Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museu De La Musica, Catalunya : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable

Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museu de la Musica, Catalunya : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable Toros Ufuk Senan MASTER THESIS UPF / 2014 Master in Sound and Music Computing Master Thesis Supervisor: Enric Guaus, Paul Poletti Department of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona ii Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museum de la Musica : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable Toros Ufuk Senan Philips Electronic Nederlands High Tech Campus 36, p.118 5656 HA Eindhoven, Netherlands Master's thesis Abstract WoodMusick project is a multi-disciplinary COST action research project. The main goal of the project is to study museum instruments and preserve their physical and acoustical properties. This paper aims to contribute the project by studying historical guitars in Museu de la Musica, Catalunya, as well as to propose a global measurement methodology for prediction of acoustical properties of guitars during the design stage. Two historical classical guitars, Torres 625 from Antonio de Torres and Labrador from romantic period are studied, in addition to a test guitar. Steady-state and impulse responses are recorded and spectral and physical properties are extracted from recordings. The results are classified with WEKA by ESSENTIA descriptors and two guitars are succefully identified and distinguished from each other. Extracted features and physical properties are observed in the latter stage and sound feature estimations are proposed.Besides the multi disciplinary nature of the study is already a challenging task, the main obstacle turned out to be to build a methodology that ensures safety of the instrument while collecting the necessary data. -

A Comprehensive Guitar Series

Bridges TM A Comprehensive Guitar Series “This new edition, in my opinion, is very close to being THE definitive word on classical guitar instruction – period.” Patrick Kearney, international concert artist and professor of classical guitar at Vanier College and Concordia University Bridges TM Introduction Bridges™ is the fourth edition of the renowned Guitar Series, originally published in 1989 to international acclaim. This edition aims to provide students with a clear, well-paced route for their musical development; to nurture the technique necessary to successfully meet those developmental challenges; and to expose students to the full range of the instrument’s repertoire. The chosen repertoire and studies at any given level fall within a carefully sequenced range of technical and musical difficulty. From the late elementary to early advanced levels students can be assured that their learning path will be well rounded and complete. Some of the most notable features of Bridges™ are: the inclusion of guitar masterpieces by such beloved guitar composers as Agustín Barrios, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and Leo Brouwer minimal fingering suggestions, leaving teachers more flexibility and a clearer score from which to work a balance of style choices for repertoire and studies in all levels The well-rounded guitarist will have an understanding of the instrument’s history as well as practical experience with a wide range of repertoire from all historical periods and styles. Guided by this principle, the series editors have drawn on more than 500 years’ worth of guitar and lute music. Each book features compositions from the Renaissance to the present day; by learning music from each style period, students will gain a comprehensive overview of the evolution of musical styles. -

The 'Romantic' Guitar Transcript

The 'Romantic' Guitar Transcript Date: Thursday, 9 October 2014 - 1:00PM Location: St. Sepulchre Without Newgate 9 October 2014 The ‘Romantic’ Guitar Professor Christopher Page Before I begin, I would like to introduce the musicians who will be performing this afternoon: the soprano Valeria Mignaco, and the guitarist, Jelma van Amersfoort. Today, the guitar is probably the most popular musical instrument in existence. With millions of devotees worldwide, it eclipses the generally more expensive piano and allows a beginner to achieve passable results much sooner than the violin. You might be surprised to discover that the guitar has a long history in England. Queen Elizabeth received a set of three guitars on New Years’ day in 1559, as a gift. Almost exactly a century later, at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Charles II returned to England with his own guitar, carried home to London by the diarist Samuel Pepys, who complained of the trouble that it gave him. Queen Anne, who died in 1714 and gave her name to some of the most elegant architecture this country has ever known, also played the guitar, and her book of lessons still survives (although it has made its way to the other side of the Atlantic). The guitar may be a light instrument, in many senses of the word, but it is not at all ephemeral. By citing those examples I do not mean to suggest that the guitar has always remained the same, or that its popularity has never waned. The guitar known to Elizabeth in 1559 was quite different to the one played by Queen Anne, and the guitars we play today are different again and immensely varied; but all the instruments concerned were recognizably guitars with a body resembling a figure eight, a circular sound-hole in the middle of the body and frets along the fingerboard. -

Guitar and Lute Music

SOLITARY REFINEMENT Music for Lute, Vihuela and Guitar Welcome to the intimate, colourful and versatile world of music for lute and guitar, instruments with an ancestry tracing back thousands of years and a fascinating repertoire reflecting the physical and social development of the instrument over the past five centuries. The music represented in the following pages traces the instrument’s journey from the refinements of the early sixteenth century to the more cutting-edge characteristics it has inspired from 20th-century composers. Collectors wishing to assemble recordings by composer will find noted representatives of successive historical periods, including the English Renaissance composer John Dowland, German baroque master Silvius Leopold Weiss, the Italian classical style of Mauro Giuliani, 19th-century Spanish greats Fernando Sor and Francisco Tárrega, plus a modern international spread of names including Joaquín Rodrigo and Leo Brouwer. There are also regional collections representative of guitar music not only from the instrument’s native Spain, but also from South American countries closely associated with the development of the instrument’s profile in the 20th century – Brazil, Argentina and Chile, for example – plus gems from Australia and Britain. Alternatively, the instrument’s range of technical and expressive capabilities can be sampled by choosing from an extensive set of solo recitals by an international roster of distinguished performers, not least in our highly successful and ever-expanding Guitar Laureate Series. Complementing the instrument’s image as a solitary instrument are recordings of ensemble works for two and three guitars, for guitar and piano, and Boccherini’s quintets for guitar and string quartet. -

A Schubertiade for Biedermeier Flute & Guitar

Gotham Early Music Scene (GEMS) presents Thursday, March 11, 2021 1:15 pm Streamed to midtownconcerts.org, YouTube, and Facebook Taya König-Tarasevich ~ Romantic flute Daniel Swenberg ~ Romantic guitar A Midday Nocturne: A Schubertiade for Biedermeier Flute & Guitar Abendlied Robert Schumann (1810–1856) [arr. J.K. Mertz] An Die Sonne Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Romanze from Rosamunde Franz Schubert Am Fenster Franz Schubert Mouvement de prière religieuse Fernando Sor (1778–1839) Nocturne Friedrich Burgmüller (1806–1874) Nacht und Träume Franz Schubert [arr. Diabelli] 9 Waltzes from D. 365 original Dances Franz Schubert [arr. Diabelli] Mondnacht Robert Schumann Taya König-Tarasevich: Romantic flute by Stefan Koch 1830 (restored M. Wenner 2019) Daniel Swenberg: 8-string guitar after Ries (Kresse 2012) Midtown Concerts are produced by Gotham Early Music Scene, Inc., and are made possible with support from St. Bartholomew’s Church, The Church of the Transfiguration, The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural affairs in partnership with the City Council; the Howard Gilman Foundation; and by generous donations from audience members. Gotham Early Music Scene, 340 Riverside Drive, Suite 1A, New York, NY 10025 (212) 866-0468 Joanne Floyd, Midtown Concerts Manager Paul Arents, House Manager Toby Tadman-Little, Program Editor Live stream staff: Paul Ross, Dennis Cembalo, Adolfo Mena Cejas, Howard Heller Christina Britton Conroy, Make-up Artist Gene Murrow, Executive Director www.gemsny.org Notes on the Program, Instruments, Editions, and Arrangements by Daniel Swenberg I suppose this program gradually formed over the years I got to know Taya and we shared our love of German Romantic poetry, particularly the song or Lied repertoire of Schubert and Schumann. -

Sept 28 to Oct 4.Txt

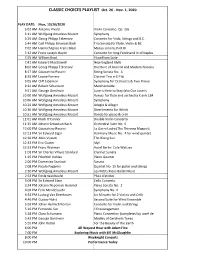

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Sept. 28 - Oct. 4, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 09/28/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto "Cuckoo" / Coucou 6:13 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 13 6:30 AM Giuseppe Tartini Violin sonata 6:45 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Capel Bond Concerto No. 4 in Seven Parts 7:11 AM Muzio Clementi Piano Sonata 7:32 AM Arcangelo Corelli Concerto Grosso No. 7 7:43 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 38 8:02 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Italian Concerto 8:16 AM Johann ChristophFriedrich Bach Trio Sonata 8:33 AM Richard Strauss Metamorphosen 9:05 AM Igor Stravinsky Violin Concerto 9:28 AM Louis Spohr Clarinet Concerto No. 2 9:53 AM Leroy Anderson Fiddle-Faddle 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ABDUCTION FROM THE SERAGLIO: Overture 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Flute Sonata 10:19 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 37 10:34 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eight variations on a march 10:49 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Keyboard Concerto after J.C. Bach 11:02 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture 11:25 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 4 12:00 PM Eric Coates The Greenland (Rhodesian March) 12:08 PM Felix Mendelssohn Organ Sonata No. 6 12:23 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Hofballtanze Walzer 12:35 PM Billy Joel Reverie (Villa D'Este) 12:46 PM John Williams (Comp./Cond.) Born on the Fourth of July: Suite 1:02 PM Carl Czerny Symphony No. 1, "Grand Symphony" 1:36 PM Johannes Brahms Fantasias 2:00 PM Johann Kaspar Mertz Am Grabe der Geliebten 2:07 PM Bernhard Henrik Crusell Clarinet Quartet No. -

A Historical and Critical Analysis of 36 Valses Di Difficolta Progressiva, Op

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 A Historical and Critical Analysis of 36 Valses di Difficolta Progressiva, Op. 63, by Luigi Legnani Adam Kossler Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A HISTORICAL AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF 36 VALSES DI DIFFICOLTA PROGRESSIVA, OP. 63, BY LUIGI LEGNANI By ADAM KOSSLER A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Adam Kossler defended this treatise on January 9, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bruce Holzman Professor Directing Treatise Leo Welch University Representative Pamela Ryan Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my guitar teachers, Bill Kossler, Dr. Elliot Frank, Dr. Douglas James and Bruce Holzman for their continued instruction and support. I would also like to thank Dr. Leo Welch for his academic guidance and encouragement. Acknowledgments must also be given to those who assisted in the editing process of this treatise. To Ruth Bass, Dr. Leo Welch, Bill Kossler, Lauren Kossler and Jamie Parks, I am forever thankful for your contributions. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical -

Oct 26 to Nov 1.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Oct. 26 - Nov. 1, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 10/26/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto, Op. 3/6 6:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 6:29 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Viola, Strings and B.C. 6:44 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Trio Sonata for Flute, Violin & BC 7:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 7:12 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto for King Ferdinand IV of Naples 7:29 AM William Byrd Fitzwilliam Suite 7:41 AM Edward MacDowell New England Idylls 8:02 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture of Ancient and Modern Nations 8:17 AM Gioacchino Rossini String Sonata No. 5 8:33 AM Louise Farrenc Clarinet Trio in E-Flat 9:05 AM Cliff Eidelman Symphony for Orchestra & Two PIanos 9:34 AM Robert Schumann Märchenbilder 9:51 AM George Gershwin Love is Here to Stay (aka Our Love is 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for flute and orchestra K anh.184 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 10:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Adagio & Allegro 10:36 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 10:51 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for piano & orch 11:01 AM Mark O'Connor Double Violin Concerto 11:35 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 4 12:00 PM Gioacchino Rossini La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie): 12:13 PM Sir Edward Elgar Harmony Music No. 4 for wind quintet 12:26 PM Allen Vizzutti The Rising Sun 12:43 PM Eric Coates Idyll 12:51 PM Franz Waxman Hotel Berlin: Cafe Waltzes 1:01 PM Sir Charles Villiers Stanford Clarinet Sonata 1:25 PM Friedrich Kuhlau Piano Quartet 2:00 PM Domenico Scarlatti Sonata 2:08 PM Nicolo Paganini Quartet No. -

Elements of Style Hongrois Within Fantaisie Hongroise, Op. 65, No.1 By

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Elements of Style Hongrois within Fantaisie Hongroise, Op.65, No. 1 by J.K. Mertz Andrew Stroud Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ELEMENTS OF STYLE HONGROIS WITHIN FANTAISIE HONGROISE, OP. 65, NO.1 BY J.K. MERTZ By ANDREW STROUD A doctoral treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Andrew Stroud defended this treatise on June 26th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bruce Holzman Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes Outside Committee Member Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my wife, mother and father. Without whom, I would fail in life and laughter. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank a few individuals for their support. Firstly, Bruce Holzman, for listening to the continued scratching of strings and never flagging. I must give many thanks to professors Mathes and Punter for agreeing to follow me on this project. I also received wonderful direction from Matanya Ophee and Richard Long, men unsurpassed in their scholarly contributions to the history of the guitar. I owe an unending debt of gratitude to Dr. Jonathan Bellman of the University of Northern Colorado, the country’s foremost scholar of style hongrois, and someone who supplied an absolutely priceless amount of help.