Gong Dingzi and the Courtesan Gu Mei: Their Romance and the Revival of the Song Lyric in the Ming-Qing Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ming-Qing Women's Song Lyrics to the Tune Man Jiang Hong

engendering heroism: ming-qing women’s song 1 ENGENDERING HEROISM: MING-QING WOMEN’S SONG LYRICS TO THE TUNE MAN JIANG HONG* by LI XIAORONG (McGill University) Abstract The heroic lyric had long been a masculine symbolic space linked with the male so- cial world of career and achievement. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming-Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in their tex- tual production, complicated the issue. This paper examines how women crossed gen- der boundaries to appropriate masculine poetics, particularly within the dimension of the heroic lyric to the tune Man jiang hong, to voice their reflections on larger historical circumstances as well as women’s gender roles in their society. The song lyric (ci 詞), along with shi 詩 poetry, was one of the dominant genres in which late imperial Chinese women writers were active.1 The two conceptual categories in the aesthetics and poetics of the song lyric—“masculine” (haofang 豪放) and “feminine” (wanyue 婉約)—may have primarily referred to the textual performance of male authors in the tradition. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming- Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in * This paper was originally presented in the Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, New York, March 27-30, 2003. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Grace S. Fong for her guidance and encouragement in the course of writing this pa- per. I would like to also express my sincere thanks to Professors Robin Yates, Robert Hegel, Daniel Bryant, Beata Grant, and Harriet Zurndorfer and to two anonymous readers for their valuable comments and suggestions that led me to think further on some critical issues in this paper. -

The Case of Wang Wei (Ca

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 5-6_full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Sufeng Xu _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Courtesan as Famous Scholar _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Courtesan as Famous Scholar T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 587-630 www.brill.com/tpao 587 The Courtesan as Famous Scholar: The Case of Wang Wei (ca. 1598-ca. 1647) Sufeng Xu University of Ottawa Recent scholarship has paid special attention to late Ming courtesans as a social and cultural phenomenon. Scholars have rediscovered the many roles that courtesans played and recognized their significance in the creation of a unique cultural atmosphere in the late Ming literati world.1 However, there has been a tendency to situate the flourishing of late Ming courtesan culture within the mainstream Confucian tradition, assuming that “the late Ming courtesan” continued to be “integral to the operation of the civil-service examination, the process that re- produced the empire’s political and cultural elites,” as was the case in earlier dynasties, such as the Tang.2 This assumption has suggested a division between the world of the Chinese courtesan whose primary clientele continued to be constituted by scholar-officials until the eight- eenth century and that of her Japanese counterpart whose rise in the mid- seventeenth century was due to the decline of elitist samurai- 1) For important studies on late Ming high courtesan culture, see Kang-i Sun Chang, The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism (New Haven: Yale Univ. -

Wing-Ming Chan) (PDF 1.5MB

East Asian History NUMBER 19 . JUNE 2000 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Ba rme As sistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Bo ard Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark An drew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W.]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Des ign and Production Helen Lo Bu siness Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT Th is is th e nineteenth issue of East Asian History in the seri es previously entitled Papers on Far EasternHistory. The journal is published twice a year Contributions to The Ed itor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and As ian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Au stralia Phone +61 2 6249 3140 Fax +61 2 6249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at th e above address Annual Subscription Au stralia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Lu Xun's Disturbing Greatness W. j. F.Jenner 27 The Early-Qing Discourse on Lo yalty Wing-ming Chan 53 The Dariyan ya, the State of the Uriyangqai of the Altai , the Qasay and the Qamniyan Ceveng (c. Z. Zamcarano) -translated by 1. de Rachewiltz and j. R. Krueger 87 Edwardian Theatre and the Lost Shape of Asia: Some Remarks on Behalf of a Cinderella Subject Timothy Barrett 103 Crossed Legs in 1930s Shanghai: How 'Modern' the Modern Woman? Francesca Dal Lago 145 San Mao Makes History Miriam Lang iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M�Y��, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Magazine advertisement for the medicine Bushiming THE EARLY-QING DISCOURSE ON LOYALTY � Wing-ming Chan �*Jkfijj The drastic shift of the Mandate of Heav en in seventeenth-century China 2 ZhangTingyu iJ1U!33: (1672-1755) et aI., provoked an identity crisis among the Chinese literati and forced them to comp., Mingshi [History of the Ming dynasty! reconsider their socio-political role in an er a of dynastic change. -

From Empire to Dynasty: the Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming

Furman Humanities Review Volume 30 April 2019 Article 10 2019 From Empire to Dynasty: The Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming Yunhui Yang '19 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Yang, Yunhui '19 (2019) "From Empire to Dynasty: The Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming," Furman Humanities Review: Vol. 30 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr/vol30/iss1/10 This Article is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Humanities Review by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM EMPIRE TO DYNASTY: THEIMPEJUALCARE ROFH ANGFU IN THE EARLY MING Yunhui Yang In 1511, a Portuguese expeditionary force, captai ned by the brilliant empire builder Afonso de Albuquerque ( 1453-1515) succeeded in establishing a presence in South east Asia with the capture of Malacca, a po1t city of strategic and commercial importance. Jn the colonial "Portuguese cen tury" that followed, soldiers garrisoned coastal forts officials administered these newly colonized territories, merchants en gaged in the lucrative spice trade, Catholic missionaries pros elytized the indigenous people and a European sojourner population settled in Southeast Asia. 1 Although this was the first tim larger numbers of indigenous people in Southeast Asia encountered a European empire , it was not the first co lonial experience for these people. Less than a century be fore the Annamese had been colonized by the Great Ming Empire from China .2 1 Brian Harri on, South-East Asia: A Short Histo,y, 2nd ed. -

Kang-I Sun Chang (孫康宜), the Inaugural Malcolm G. Chace

CURRICULUM VITAE Kang-i Sun Chang 孫 康 宜 Kang-I Sun Chang: Short Bio Kang-i Sun Chang (孫康宜), the inaugural Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University, is a scholar of classical Chinese literature, with an interest in literary criticism, comparative studies of poetry, gender studies, and cultural theory/aesthetics. The Chace professorship was established by Malcolm “Kim” G. Chace III ’56, “to support the teaching and research activities of a full-time faculty member in the humanities, and to further the University’s preeminence in the study of arts and letters.” Chang is the author of The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late Tang to Northern Sung; Six Dynasties Poetry; The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism; and Journey Through the White Terror. She is the co-editor of Writing Women in Late Imperial China (with Ellen Widmer), Women Writers of Traditional China (with Haun Saussy), and The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature (with Stephen Owen). Her translations have been published in a number of Chinese publications, and she has also authored books in Chinese, including Wenxue jingdian de tiaozhan (Challenges of the Literary Canon), Wenxue de shengyin (Voices of Literature), Zhang Chonghe tizi xuanji (Calligraphy of Ch’ung-ho Chang Frankel: Selected Inscriptions), Quren hongzhao (Artistic and Cultural Traditions of the Kunqu Musicians), and Wo kan Meiguo jingshen (My Thoughts on the American Spirit). Her current book project is tentatively titled, “Shi Zhecun: A Modernist Turned Classicist.” At Yale, Chang is on the affiliated faculty of the Department of Comparative Literature and is also on the faculty associated with the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program. -

1 Emperor Versus Moral Exemplar: Huang Daozhou's (1585-1646)

Emperor versus Moral Exemplar: Huang Daozhou's (1585-1646) Fateful Performance of Zhongxiao Ethics Ying Zhang In the historical documentation of the last dynastic transition in Chinese history, from the Ming to the Qing, the literatus-official Huang Daozhou stands out as the loyal literatus- official, the impeccable Confucian man. Prior to the Ming fall, Huang Daozhou was known as an upright official and erudite literatus. Captured by the Manchus after an ill-prepared military expedition was shattered, he refused to offer his allegiance. After brief imprisonment he was executed and thus became a loyalist martyr for the Ming cause. Huang Daozhou strove to become “a perfect man” (wanren or zhiren), and during his lifetime was indeed considered to exemplify the Confucian virtues. Late-Ming literatus and geographer Xu Hongzu’s (1587-1641) has so commented: “There is only one perfect man (zhiren), Shizhai (Huang Daozhou). His calligraphy and painting are the best among the Academicians, his essays the best in this dynasty, his character the best in the country, and his scholarship—inherited directly from Duke Zhou and Confucius—the best in history.”1 After the dynastic transition, Sun Qifeng (1584-1675), a widely respected Confucian thinker, identified Huang as one of the only two figures throughout the Ming dynasty “whose loyalty was complete” (zhong dao zuse), because his martyrdom was the most fearless, best manifesting his achievements in Confucian learning.2 Such extravagant eulogies, though reflecting people’s admiration for an extraordinary figure, have often been quoted in historical scholarship as authoritative evidence.3 But how did Huang Daozhou come to 1 epitomize moral perfection and what does it tell us about late-Ming moral-political environment? To answer these questions is to draw attention to the centrality of zhongxiao (literally “loyalty-filial piety”) not just in Huang’s moral reputation, but also in dynastic politics and in literati historical consciousness—at once as an ideal, a practice, and a political tool. -

Ming China' Anew: the Ethnocultural Space in a Diverse Empire-With Special Reference to the 'Miao Territory' Yonglin Jiang Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College East Asian Studies Faculty Research and East Asian Studies Scholarship 2018 Thinking About the 'Ming China' Anew: The Ethnocultural Space In A Diverse Empire-With Special Reference to the 'Miao Territory' Yonglin Jiang Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/eastasian_pubs Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Custom Citation Jiang, Y. 2018. "Thinking About the 'Ming China' Anew: The thnocE ultural Space In A Diverse Empire-With Special Reference to the 'Miao Territory'." Journal of Chinese History 2.1: 27-78. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/eastasian_pubs/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Chinese History 2 (2018), 27–78 doi:10.1017/jch.2017.27 . Jiang Yonglin THINKING ABOUT “MING CHINA” ANEW: THE ETHNOCULTURAL SPACE IN A DIVERSE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms EMPIRE —WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE “MIAO TERRITORY”* Abstract By examining the cultural identity of China’s Ming dynasty, this essay challenges two prevalent perceptions of the Ming in existing literature: to presume a monolithic socio-ethno-cultural Chinese empire and to equate the Ming Empire with China (Zhongguo, the “middle kingdom”). It shows that the Ming constructed China as an ethnocultural space rather than a political entity. Bryn Mawr College, e-mail: [email protected]. , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at *The author is grateful to a large number of individuals and institutions for their insightful critiques and generous support for this project. -

The Textual and Imaginary World of Ho Kyongbon (1563-1589) Young

The Textual and Imaginary World of Ho Kyongbon (1563-1589) Young Kweon Department of East Asian Studies McGill University Montreal, Canada May 2003 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts Universal Copyright © 2003 Young Kweon Acknowledgements My sincerest thanks go to my supervisor Professor Grace S. Fong for her guidance and invaluable comments on this thesis. I am greatly indebted to her for opening my eyes to the world of women's Classical Chinese literature. Without her time and efforts put into my study at McGill, it would have been impossible for me to finish this thesis. I am also honored and grateful to Professor Stephen Owen, who gave me insightful comments on Ho Kyongbon's poetry in the text reading session held at McGill University. His extensive knowledge on Tang poetry and scholarly interpretation of Ho's poetry expanded my understanding of it. My sincere thanks also go to Professor Yi Chang-u at Yongnam University for his encouragement and scholarly comments. He has been a model of a devoted and exceptional scholar to many of us who had a chance to know him. I would like to thank some of my fellow graduate students who took the graduate courses with me. Their comments in translating Ho Kyongbon's poems were indispensable. I am also extremely grateful to Jim Bonk who put so much effort into reading my thesis, carefully editing it. Without his help, my journey would have been prolonged. Finally, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my family members. -

WU WENYING and the ART of SOUTHERN SONG CI POETRY By

WU WENYING AND THE ART OF SOUTHERN SONG CI POETRY by GRACE SIEUGIT FONG B.A., University Of Toronto, 1975 M.A., University Of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department Of Asian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1984 © Grace Sieugit Fong, 1984 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Asian Studies The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date: October 15, 1984 i i Abstract The thesis studies the ci_ poetry of Wu Wenying (c.1200- c.1260) in the context of Southern Song c_i_ poetics and aims to establish its significance in contemporary developments and in the tradition of ci criticism. Chapter One explores the moral and aesthetic implications of Wu's life as a "guest-poet" patronized by officials and aristocrats, and profiles two relationships in Wu's life, the loss of which generated a unique corpus of love poetry. To define the art of Southern Song c_i, Chapter Two elucidates current stylistic trends, poetics, and aesthetics of ci, examining critical concepts in two late Song treatises, the Yuefu zhimi and Ciyuan. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 507 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2020) Guangling Ci Circle and Its "Amorous Ci" Chimed Activities Qinglv Huang1,* Suxiang Yu2 1College of Liberal Arts, Tibet University, Lhasa, Tibet 850000, China 2College of Arts and Social Science, Panzhihua University, Panzhihua, Sichuan 617000, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Through the literature analysis, the paper probes into the features of Guangling Ci Circle (ci, a type of classical Chinese poetry, originating in the Tang Dynasty and fully developed in the Song Dynasty) as well as its amorous ci chimed activities, as Guangling Ci Circle has actually become an important milestone to carry forward the practical changes and theoretical construction of prosperity of ci poem, especially the amorous ci in Qing Dynasty, and laid the solid foundation for the far-reaching and significant development of ci poem, especially the amorous ci in Qing Dynasty. As the ci poems were mainly under the theme of love between men and women, the research value of amorous ci cannot be ignored absolutely. Keywords: Guangling Ci Circle, Amorous Ci, chimed activities for the first time in the early Qing Dynasty. It was large I. INTRODUCTION in scale, wide in lineup, high in self-consciousness and The concept of "Guangling Ci Circle" can be found vigorous in momentum. first in the exposition of Yan Dichang in his "History of The amorous ci chimed activities of Guangling Ci Ci in the Qing Dynasty": "When the tinder of 'Yun- Circle not only contributed to the birth of important chien' lit by Chen Zilong in Zhengjiang and other forms of artistic expression in the creation of amorous provinces were about to burn out, a group of his ci such as "feng ren zhi zhi" and "a tune with eight Jiangdong disciples had been active in the cultural pieces", etc., but also became a milestone to promote centers of Suzhou, Wuxi and Changzhou etc. -

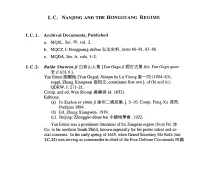

I. C. NANJING and the HONGGUANG Regil\-Te I. C .1

I. C. NANJING AND THE HONGGUANG REGIl\-tE I. C .1. Archival Documents, Published a. MQSL. Ser. E¥', vol. 2. b. MQCZ. I: Hongguang shiliao 5b*~fL items 66-81, 83-86. c. MQDA. Ser. A, vols. 1-2. I.C.2. Baida Shanrenji B1J:I1IA~ rYan Guguji !mtlt!. (b); Yan Gugu quan ~ji (c)], 6 j. Yan Ermei rmmm rYan Gugu]: Nianpu by Lu Yitong ~-~ (1804-63), suppl. Zhang Xiangwen ~:ffi)C constitutes first two j. of (b) and (c); QDRW, I: 211-21. Compo and ed. Wan Shouqi ~~m (d. 1652). Editions: (a) In Xuzhou er yiminji ~1H=J1~~,j. 5-10. Compo Feng Xu l~~. Prefaces 1894. (b) Ed. Zhang Xiangwen. 1919. (c) Beijing: Zhongguo dixue hui r:p~i~~fr, 1922. Yan Ermei was a prominent litterateur of the Jiangnan region (from Pei 1$ Co. in far northern South Zhili), known especially for his poetic talent and so cial concerns. In the early spring of 1645, when Grand Secretary Shi Kefa (see I.C.24) was serving as commander in chief of the Four Defense Commands [9. I. C. Nanjing 221 north of the Yangzi River, Yan was invited to join him as an adviser. Juan 6 of this collection contains a letter from Yan to Shi (drastically abbreviated in edition [cD, which was prompted by the assassination of one of the defense comman ders, Gao Jie ~~, a former roving rebel. Yan urges Shi to tum that to his advantage by proceeding vigorously to incorporate Gao's semi-independent troops under regular Ming military commands and to advance on the same prin ciple to enlist the freelance militarists and erstwhile rebels of the North China plain in patriotic resistance to the Qing. -

List of Works Cited

LIST OF WORKS CITED The list of works cited is subdivided into Abbreviations, Primary Sources and Secondary Sources. In the references a colon separates a volume number and a page number; a period separates a juan ~ (section) or hui @) (chapter) number and a page number. In the list of primary sources the symbol '§' means that a subsequent item is contained in the work cited . .ABBREVIATIONS FHQS Fuhui quanshu fiH!:i:il. By Huang Liuhong Jt;\~. Author's preface 1694. Ed. Obata Yukihiro JjvJ:8J1ilfifi. Repr. Yamane Yukio L.Lrfl¥~. Tokyo: Kyfiko, 1973. JPMCH Jin Ping Mei cihua 1rt)fi~ti.iJ~. 4 vols. Hong Kong: Xinghai wenhua, 1987. T-YYZ Xingshi yinyuan "l!i!!:t@~. By Xi Zhou sheng gg.R'i]1:_. 2 vols. Taibei: Lianjing, 1986. TDT Xingshi yinyuan zhuan ~i!!:Wil~'f.i. By Xi Zhou sheng iffi .R'i11:.. Tongdetang edn. 20 vols. Repr. Beijing: Wenxue guji, 1988. Y YZ Xingshi yinyuan zhuan ~1!!:Wi1~1$. By Xi Zhou sheng iffi .R'i11:.. 3 vols. Shanghai: Guji, 1981, repr. 1985. Daria Berg - 9789004453401 Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 06:24:56AM via free access 368 LIST OF WORKS CllED PRIMARY SOURCES Anyatang gao ~~ft~¥.6. By Chen Zilong ll*r!J~. Repr. Taibei: Weiwen, 1977. Baiyuji Bftltr~. By Tu Long ~~it Repr. Taibei: Weiwen, 1977. Beichuang suoyu ::It'&~~. By Yu Yonglin ~:lk~. Shanghai: Shangwu, 1936. Beishi ::It~. By Li Yanshou $%f:ft. Beijing: Zhonghua, 1974. Bencao gangmu :L$=1jrf.liil §. By Li Shizhen $Bit~. Beijing: Renmin weisheng, 1982. Bizhu if~. By Mo Shilong ~~fm.