The Mitsve Tants Injerusalemite Weddings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamford Hill.Pdf

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Housing Studies on Volume 33, 2018. Schelling-Type Micro-Segregation in a Hassidic Enclave of Stamford-Hill Corresponding Author: Dr Shlomit Flint Ashery Email [email protected] Abstract This study examines how non-economic inter- and intra-group relationships are reflected in residential pattern, uses a mixed methods approach designed to overcome the principal weaknesses of existing data sources for understanding micro residential dynamics. Micro-macro qualitative and quantitative analysis of the infrastructure of residential dynamics offers a holistic understanding of urban spaces organised according to cultural codes. The case study, the Haredi community, is composed of sects, and residential preferences of the Haredi sect members are highly affected by the need to live among "friends" – other members of the same sect. Based on the independent residential records at the resolution of a single family and apartment that cover the period of 20 years the study examine residential dynamics in the Hassidic area of Stamford-Hill, reveal and analyse powerful Schelling-like mechanisms of residential segregation at the apartment, building and the near neighbourhood level. Taken together, these mechanisms are candidates for explaining the dynamics of residential segregation in the area during 1995-2015. Keywords Hassidic, Stamford-Hill, Segregation, Residential, London Acknowledgments This research was carried out under a Marie Curie Fellowship PIEF-GA-2012-328820 while based at Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA) University College London (UCL). 1 1. Introduction The dynamics of social and ethnoreligious segregation, which form part of our urban landscape, are a central theme of housing studies. -

(° Evved 3 3 4 9

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2010 benefit trust or private foundation ) Department of the Treasury Open to Public organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service ► The Inspection A For the 2010 calendar year, or tax year beginning and ending B checlk if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable chan BET YISRAEL Nam acChanaannge Doin g Business As 95-4752695 =rewan Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/su ite E Telephone number =aBd'" 13347 VENTURA BLVD. 818.385.3200 C:]eturnded r City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 G Gross receipts $ 314253 , ==1'°a- SHERMAN OAKS , CA 91423-3912 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer. for affiliates? Yes IKI No 1 13347 VENTURA BLVD . SHERMAN OAKS , CA H(b) Are all affiliates included? =Yes =No I Tax-exempt status- ® 501 ( c )( 3 ) =501 (c )( 1 ( insert no. ) El 4947(a )( 1 ) or El 527 If "No," attach a list. (see Instructions) J Website: Op, N A H(c) Grou p exem ption number ► K Form of organization: ® Corporation 0 Trust = Association 0 Other ► L Year of formation: 19 9 O M State of le al domicile: C2 Part I Summary y 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Torah Wellsprings A4.Indd

Beshalach diritto d'autore 20ϮϬ di Mechon Beer Emunah [email protected] Traduzione a cura del team VedibartaBam Table of Contents Torah Wellsprings - Beshalach Shabbos of Emunah .........................................................................................................4 Believe in Yourself ...........................................................................................................5 The Hand of Emunah .......................................................................................................8 Bitachon is the root of success in Avodas Hashem ...................................................9 Kriyas Yam Suf in the merit of Bitachon...................................................................10 Hashem Acts with Us as We act with Him ................................................................11 The War with Amalek ...................................................................................................13 A Moment of Emunah ...................................................................................................14 Bitachon ...........................................................................................................................14 Feeding Birds on Shabbos Shirah ..............................................................................16 The Struggle to Have Emunah .....................................................................................17 Hashem Reminds Us .....................................................................................................18 -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) SH EVI’I SHEL PESACH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Shevi’i Shel Pesach – Kerias Yam Suf Walking on Dry Land Even in the Sea “And Bnei Yisrael walked on dry land in the sea” (Shemos 14:29) How can you walk on dry land in the sea? The Noam Elimelech , in Likkutei Shoshana , explains this contradictory-sounding pasuk as follows: When Bnei Yisrael experienced the Exodus and the splitting of the sea, they witnessed tremendous miracles and unbelievable wonders. There are Tzaddikim among us whose h earts are always attuned to Hashem ’s wonders and miracles even on a daily basis; they see not common, ordinary occurrences – they see miracles and wonders. As opposed to Bnei Yisrael, who witnessed the miraculous only when they walked on dry land in the sp lit sea, these Tzaddikim see a miracle as great as the “splitting of the sea” even when walking on so -called ordinary, everyday dry land! Everything they experience and witness in the world is a miracle to them. This is the meaning of our pasuk : there are some among Bnei Yisrael who, even while walking on dry land, experience Hashem ’s greatness and awesome miracles just like in the sea! This is what we mean when we say that Hashem transformed the sea into dry land. Hashem causes the Tzaddik to witness and e xperience miracles as wondrous as the splitting of the sea, even on dry land, because the Tzaddik constantly walks attuned to Hashem ’s greatness and exaltedness. -

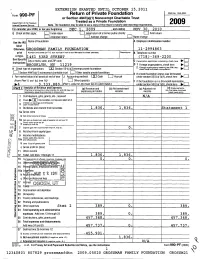

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , ma r C h 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 275 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Property from the Library of a New England Scholar ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 21st March, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Maymyo” Sale Number Fifty Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . -

Fine Judaica

t K ESTENBAUM FINE JUDAICA . & C PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, GRAPHIC & CEREMONIAL ART OMPANY F INE J UDAICA : P RINTED B OOKS , M ANUSCRIPTS , G RAPHIC & C & EREMONIAL A RT • T HURSDAY , N OVEMBER 12 TH , 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY THURSDAY, NOV EMBER 12TH 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 115 Catalogue of FINE JUDAICA . Printed Books, Manuscripts, Graphic & Ceremonial Art Featuring Distinguished Chassidic & Rabbinic Autograph Letters ❧ Significant Americana from the Collection of a Gentleman, including Colonial-era Manuscripts ❧ To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 12th November, 2020 at 1:00 pm precisely This auction will be conducted only via online bidding through Bidspirit or Live Auctioneers, and by pre-arranged telephone or absentee bids. See our website to register (mandatory). Exhibition is by Appointment ONLY. This Sale may be referred to as: “Shinov” Sale Number Ninety-One . KESTENBAUM & COMPANY The Brooklyn Navy Yard Building 77, Suite 1108 141 Flushing Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11205 Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Zushye L.J. Kestenbaum Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Judaica & Hebraica: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Shimon Steinmetz (consultant) Fine Musical Instruments (Specialist): David Bonsey Israel Office: Massye H. Kestenbaum ❧ Order of Sale Manuscripts: Lot 1-17 Autograph Letters: Lot 18 - 112 American-Judaica: Lot 113 - 143 Printed Books: Lot 144 - 194 Graphic Art: Lot 195-210 Ceremonial Objects: Lot 211 - End of Sale Front Cover Illustration: See Lot 96 Back Cover Illustration: See Lot 4 List of prices realized will be posted on our website following the sale www.kestenbaum.net — M ANUSCRIPTS — 1 (BIBLE). -

GRASSHOPPERS in the FIELDS – a THOUGHT on SELF IMAGE We Were in Our Own Eyes As Grasshoppers, and So Were We in Their Eyes

RAV AVRAHAM CHAIM TANZER SPEAKS SHELACH “To share, to care. To make the world a better place….” Parsha favorites of Moreinu HaRav Avraham Chaim Tanzer zt’l. Including his uplifting and edifying teachings. Ideas and values with with he raised and educated 4 generations, including lessons gleaned from his great character. Brought to you by Yad Avraham. Compiled and elucidated by Rav Dov Tanzer le’iluy nishmas Abba Mari hk’m. Please share at your table as an Aliyas Neshama has no integrity, and has no essence. Life is a GRASSHOPPERS IN THE FIELDS – A picture. THOUGHT ON SELF IMAGE Thus, Rav Menachem Mendel of Kotzk declared, the Spies should have been so יוַנְּהִ בְּ עֵינֵינּו כַחֲגָבִ ים וְּכֵןהָיִינּו בְּ עֵינֵיהֶם focused on their mission, and their essence as We were in our own eyes as People of Hashem, that their appearance in grasshoppers, and so were we in their the eyes of the locals couldn’t impact them. eyes Actually, we have no true and accurate way of knowing how we appear to others. Hashem could plant in their eyes to see the Spies as Abba used to often repeat the idea of the Angels of Heaven with frightful powers. Kotzker Rebbe, who explained that the real sin of the ten spies, was not really that they We see that when people base their identity returned with an alarming report – because on others, their lives are about comparisons, that is, in fact, how they saw the situation. external and inappropriate comparisons, since Rather, the real ‘Chet’ lies in these words: ‘and you never know what is really going on in some so we were in their eyes’.