Popular Culture and Queer Representation: a Critical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pearl Boy Vibrator

Pearl Boy Vibrator This is our biggest selling model in the vibrators. It is a multi-speed vibrator with rabbit clitoris stimulator and rotating pearls for internal stimulation. Ensuring your ultimate PLEASURE! The most popular and famous “orgasm machine” on the market for its price range is the Pearl Boy. Manufactured in Japan, this vibrator has durability and quality written all over it. Its functionality is very diverse and has a few functions available, making it a real favourite. The device is quiet, powerful and smooth, filling the top qualities looked for by women. The Pearl Boy has 2 slide controllers allowing you to increase or decrease intensity for your own personal pleasure. One is for the pearl rotation of the vibrators shaft giving you a stimulating internal sensation! The movement of the pearls rotating inside is very pleasurable, and for some, very stimulating for the G-Spot. The other slide control is for the clit tickler. The tickler on the Pearl Boy is purrrrfection! They have mastered the right balance of firmness in the V-shaped tickler which also, unlike many others, vibrates slightly from side to side giving you double the stimulation while speed adjustable. Due to the side to side motion of the tickler, this makes the Pearl Boy also an excellent vibrator to be used with a partner, giving them more ability to please you with this toy! Operates on 3 AA Batteries. Not Included Companion Products LUBE AA Batteries Helmet Hammer ©Intimate Whispers 2014-17 Gigi – The Rechargeable Silicone Toy When your GiGi arrives you will find it to be luxuriously packaged! The outside packaging will match the colour of the product inside. -

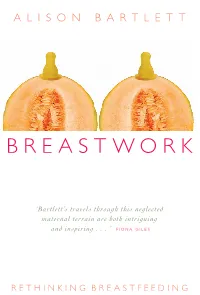

B R E a S T W O

BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT ‘BREASTWORK is a beautifully written and accessible guide to the many unexplored cultural meanings of breastfeeding in contemporary society. Of all our bodily functions, lactation is perhaps the most mysterious and least understood. Promoted primarily in terms of its nutritional benefi ts to babies, its place – or lack of it – in Western culture remains virtually unexplored. Bartlett’s travels through this neglected maternal terrain are both intriguing and inspiring, as she shows how breastfeeding can be a transformative act, rather than a moral duty. Looking at breastfeeding in relation to medicine, the media, sexuality, maternity and race, Bartlett’s study BREASTWORK provides a uniquely comprehensive overview of the ways in which we represent breastfeeding to ourselves and the many arbitrary limits we place around it. BREASTWORK makes a fresh, thoughtful and important contribution BARTLETT to the new area of breastfeeding and cultural studies. It is essential reading for ‘Bartlett’s travels through this neglected all students of the body, whether in the health professions, the social sciences, maternal terrain are both intriguing or gender and cultural studies – and for and inspiring . ’ F IONA GILES all mothers who have pondered the secrets of their own breastly intelligence.’ FIONA GILES author of Fresh Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts UNSW PRESS ISBN 0-86840-969-3 � UNSW RETHINKIN G BREASTFEEDING 9 780868 409696 � PRESS BreastfeedingCover2print.indd 1 29/7/05 11:44:52 AM BreastWork04 28/7/05 11:30 AM Page i BREASTWORK ALISON BARTLETT is the Director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of Western Australia. -

“Sky Blossom,” a “Variety Top 2021 Awards Season Contender,” Brings Innovative Film Launch Strategy to New York’S Famed 92Y

“SKY BLOSSOM,” A “VARIETY TOP 2021 AWARDS SEASON CONTENDER,” BRINGS INNOVATIVE FILM LAUNCH STRATEGY TO NEW YORK’S FAMED 92Y First “all-inclusive” documentary of the year brings together Latino, Black, Asian, Native and White American Narratives. Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell join forces as Official Congressional Honorary Co-Chairs in rare bipartisan support for new film on student “care heroes.” January 9, 2021 (New York, NY)— The 92Y, one of the leading cultural and community center in New York City, will present an exclusive screening and virtual conversation around the acclaimed documentary film “Sky Blossom: Diaries of the Next Greatest Generation” on Monday, January 11 at 6:30pET. Sky Blossom provides a raw, uplifting window into the lives of 24.5 million students taking care of family with disabilities across America. The film in October was named by Variety as one of the “Top 25 2021 Awards Season Contenders.” “Viewers often say they cry, but because they are so inspired by the courage the students in the film demonstrate,” says the film’s director. Intersectional and All-Inclusive The film follows five students over three years, from Latino, Black, Asian, Native, and White American families in the military community. During a year of wide-reaching headlines of George Floyd, these families’ multicultural stories of homelessness, poverty, life and death, and more give us a look into what it means to be a Person of Color, a caregiver, a veteran, and more. The field film crew was 100% female, as was the composer of the original soundtrack and six original theme songs. -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2013 Court Green: Dossier: Sex Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Sex" (2013). Court Green. 10. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 10 COURT 10 EDITORS Tony Trigilio and David Trinidad MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jessica Dyer EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS S’Marie Clay, Abby Hagler, Jordan Hill, and Eugene Sampson Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of English. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair, Department of English; Deborah H. Holdstein, Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Louise Love, Interim Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. Our submission period is March 1-June 30 of each year. Please send no more than five pages of poetry. We will respond by August 31. Each issue features a dossier on a particular theme; a call for work for the dossier for Court Green 11 is at the back of this issue. Submissions should be sent to the editors at Court Green, Columbia College Chicago, Department of English, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605. -

VAGINA Vagina, Pussy, Bearded Clam, Vertical Smile, Beaver, Cunt, Trim, Hair Pie, Bearded Ax Wound, Tuna Taco, Fur Burger, Cooch

VAGINA vagina, pussy, bearded clam, vertical smile, beaver, cunt, trim, hair pie, bearded ax wound, tuna taco, fur burger, cooch, cooter, punani, snatch, twat, lovebox, box, poontang, cookie, fuckhole, love canal, flower, nana, pink taco, cat, catcher's mitt, muff, roast beef curtains, the cum dump, chocha, black hole, sperm sucker, fish sandwich, cock warmer, whisker biscuit, carpet, love hole, deep socket, cum craver, cock squeezer, slice of heaven, flesh cavern, the great divide, cherry, tongue depressor, clit slit, hatchet wound, honey pot, quim, meat massager, chacha, stinkhole, black hole of calcutta, cock socket, pink taco, bottomless pit, dead clam, cum crack, twat, rattlesnake canyon, bush, cunny, flaps, fuzz box, fuzzy wuzzy, gash, glory hole, grumble, man in the boat, mud flaps, mound, peach, pink, piss flaps, the fish flap, love rug, vadge, the furry cup, stench-trench, wizard's sleeve, DNA dumpster, tuna town, split dick, bikini bizkit, cock holster, cockpit, snooch, kitty kat, poody tat, grassy knoll, cold cut combo, Jewel box, rosebud, curly curtains, furry furnace, slop hole, velcro love triangle, nether lips, where Uncle's doodle goes, altar of love, cupid's cupboard, bird's nest, bucket, cock-chafer, love glove, serpent socket, spunk-pot, hairy doughnut, fun hatch, spasm chasm, red lane, stinky speedway, bacon hole, belly entrance, nookie, sugar basin, sweet briar, breakfast of champions, wookie, fish mitten, fuckpocket, hump hole, pink circle, silk igloo, scrambled eggs between the legs, black oak, Republic of Labia, -

Sex and Diabetes: a Thematic Analysis of Gay and Bisexual Men's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aston Publications Explorer Jowett et al (2012) Sex and Diabetes Sex and Diabetes: A Thematic Analysis of Gay and Bisexual Men’s Accounts Adam Jowett1, Elizabeth Peel and Rachel L. Shaw Please cite the published version of this paper available from the publisher’s website: http://hpq.sagepub.com/content/17/3/409.abstract Jowett, A., Peel, E., & Shaw, R.L. (2012). Sex and diabetes : a thematic analysis of gay and bisexual men's accounts. Journal of health psychology, 17 (3), 409-418. DOI: 10.1177/1359105311412838 ABSTRACT Around 50 per cent of men with diabetes experience erectile dysfunction. Much of the literature focuses on quality of life measures with heterosexual men in monogamous relationships. This study explores gay and bisexual men’s experiences of sex and diabetes. Thirteen interviews were analysed and three themes identified: erectile problems; other ‘physical’ problems; and disclosing diabetes to sexual partners. Findings highlight a range of sexual problems experienced by non-heterosexual men and the significance of the cultural and relational context in which they are situated. The personalized care promised by the UK government should acknowledge the diversity of sexual practices which might be affected by diabetes. Keywords diabetes, diversity, men’s health, qualitative methods, sexual health, sexuality 1 Corresponding author: Dr Adam Jowett, Department of Psychology & Behavioural Sciences, Coventry University, CV1 5FB, UK. Email: [email protected] 1 Jowett et al (2012) Sex and Diabetes INTRODUCTION Diabetes is a group of disorders that interferes with the body’s ability to use glucose in the blood properly and affects over two million people in England alone (Department of Health (DoH), 2010). -

Appearances and Grooming Standards As Sex Discrimination in the Workplace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 56 Issue 1 Fall 2006 Article 9 2006 Appearances and Grooming Standards as Sex Discrimination in the Workplace Allison T. Steinle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Allison T. Steinle, Appearances and Grooming Standards as Sex Discrimination in the Workplace, 56 Cath. U. L. Rev. 261 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol56/iss1/9 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPEARANCE AND GROOMING STANDARDS AS SEX DISCRIMINATION IN THE WORKPLACE Allison T. Steinle' "It is amazing how complete is the delusion that beauty is good- ness."' Since the inception of Title VII's prohibition against employment dis- crimination on the basis of sex,2 women have made remarkable progress in their effort to shatter the ubiquitous glass ceiling3 and achieve parity + J.D. Candidate, 2007, The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law; A.B., 2004, The University of Michigan. The author would like to thank Professor Jeffrey W. Larroca for his invaluable guidance throughout the writing process and Peggy M. O'Neil for her excellent editing and advice. She also thanks her family and friends for their unending love, support, and patience. 1. LEO TOLSTOY, The Kreutzer Sonata, in THE KREUTZER SONATA AND OTHER STORIEs 85, 100 (Richard F. Gustafson ed., Louise Shanks Maude et al. -

Art of Fellatio

Head of the Class The Art of Fellatio ~ 1 ~ Amare - Amore, that’s out motto…meaning to love with love, is dedicated to teaching the joys of experiencing deeply powerful intimate relationships. We provide the tools and techniques to achieve explosive and dynamic sexual intimacy, whether in a committed relationship or experiencing life solo. We strive to provide insightful and accurate information, quality products and services and life changing moments of ecstasy. Credits: Deep Memories.com Libida.com ~ 2 ~ Head of the Class: The Art of Fellatio Is there a man alive who wouldn’t sell his soul for a killer blowjob? Even if you feel you give damn good fellatio already, you may find something in this workshop that may further blow your man’s mind. If you are a novice, read the tips and choose two or three suggestions you would like to try. Not everything here will appeal to you or your lover. But everyone’s sexuality changes and evolves with time, so there is room for growth and learning in your encounters even with a longtime partner. Blowjobs aren't just for men's pleasure. Many women say the feeling of control it gives them combined with the oral stimulation is a turn- on in its own right. And the more it turns her on, the more exciting it is for him. Read on for tips and techniques to make a blowjob an ultimately satisfying experience for all involved. The Anatomy Know what you're getting into: Glans: The head of the penis Frenulum: The underside of the glans; ** the most sensitive part ** Shaft: The length of the penis Perineum: The area between the anus and the testicles Testicles: Where sperm is made and stored for ejaculation. -

Roll a D100 42 Times (Subsequent Rerolls Will, Almost Certainly, Be Called for However)

The Serious Business Waifu CYOA v. 2.0 by NyuuLucy “because pictures are for casuals” Note: Its easier if instead of rolling in post you use a dedicated dice roller like https://www.wizards.com/dnd/dice/dice.htm Roll a D100 42 times (subsequent rerolls will, almost certainly, be called for however) ● Your waifu posseses [20] total trait slots. ● To fill these slots you must first freely select 1 trait from any of the categories. ● Her second trait slot must be filled by a trait from the “Endearing Foible” category. To determine which foible roll twice on the foible chart and pick one. ● The remaining slots may be filled by selecting traits freely from your PTP (potential trait pool). Your potential trait pool is generated by rolling for a specified number of traits from each category. To ensure no single category is over or under represented traits from each individual category must fill a specified minimum number of slots and may not fill more than a specified maximum number of slots. ● If you dislike all of your available traits from a given category you may reroll that category however for each such reroll you must fill an additional slot with a foible generated in the same manner as the first (roll two pick one) allowing fewer total choices from your PTP. ● If you roll the same number more than once when rolling for a particular category that trait instantly and irrevocably occupies a trait slot ● If you should happen to roll 47 twice at the same time you must roll once on the Critical Hit category (these options do not occupy trait slots) ● Some traits provide an additional “bonus Trait” unless otherwise specified they do not occupy one of your 20 trait slots enabling your waifu to posses more than 20 total traits. -

Couples and Coupling in the Public Sphere: a Comment on the Legal History of Litigating for Lesbian and Gay Rights

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1993 Couples and Coupling in the Public Sphere: A Comment on the Legal History of Litigating for Lesbian and Gay Rights Mary Anne Case Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Anne Case, "Couples and Coupling in the Public Sphere: A Comment on the Legal History of Litigating for Lesbian and Gay Rights," 79 Virginia Law Review 1643 (1993). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COUPLES AND COUPLING IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE: A COMMENT ON THE LEGAL HISTORY OF LITIGATING FOR LESBIAN AND GAY RIGHTS Mary Anne Case* O F three possible focal points for gay identity-the individual, the community, and the couple-the couple is the least visible in liti- gation about the public sphere rights of gay men and lesbians. Using as my starting point the cases collected in Professor Patricia Cain's litigation history,' I shall explore in this Commentary the implica- tions of the couple's absence from most public sphere cases and its uneasy, shadowy presence within others. It should not be surprising that the couple is both a suppressed and a contested element in gay rights litigation. Coupling, in two senses of the word, is both defining and problematic for gay men and lesbians in this society. -

Talking About Sex: Narrative Approaches to Discussing Sex Life in Therapy

TalkingNARRATIVE APPROACHES about TO sex: DISCUSSING SEX LIFE IN THERAPY AUTHOR RON FINDLAY Ron Findlay, from Melbourne Australia, works part-time as co-ordinator and lecturer for the La Trobe University / Bouverie Centre’s Graduate Certificate in Narrative Therapy, part-time in private practice as a therapist with a narrative focus, and part-time as a parent. He has been using narrative therapy practices since the mid-1980s. He can be contacted c/o [email protected] How do we discuss sex issues in therapy with a narrative and post-structuralist, post- colonial approach? This paper discusses the ethics and practices of narrative approaches to talking about sex in therapy. It discusses ways to reduce the influence of shame and embarrassment, promote local knowledge and skills, and to minimise the impact of the gender and sexuality of the therapist. Keywords: sex, therapy, narrative therapy, Foucault, ethics, externalising, co-research, outsider witness, scaffolding THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NARRATIVE THERAPY AND COMMUNITY WORK 2012 No. 2 www.dulwichcentre.com.au 11 What is my own purpose for this article and what is its THE PROBLEM OF VERBalisation history? My longstanding interest in talking about sex derived partly from a curiosity about sex when growing I don’t try to write an archaeology of sexual fantasies. up, and partly from exposure to the tail end of the I try to make an archaeology of discourse about sexuality, ‘alternative culture’ and ‘sexual revolution’ of the 1960s which is really the relationship between what we do, what and 1970s which included an encouragement to talk we are obliged to do, what we are forbidden to do in the about sex as a healthy, positive and ‘liberating’ thing to do. -

Technophobia VIII Round Ten

Technophobia VIII Round Ten Caltech Jordan Boyd-Graber November 10, 2003 1 Caltech Tossups, Round Ten 1. Geminus, the most famous one, was on the north side of Rome's forum. When Rome was at war it was opened, and when it was closed, Rome was at peace. According to Livy, the austere rectangular bronze structure with doors on either side was closed only twice between Octavian and Numa Pompilius. Particular attention was paid to how legions would march through them on the start of a campaign or returning from one because of the numerous bad omens that could transpire. For ten points, identify these ceremonial gateways named after the Roman God of beginnings and ends whose name is attached to the first month. Answer: Janus, plural: Jani 2. It circles around Betelgeuse [beetlejuice] at a distance equivalent to thirty times the space between the Sun and Earth, receiving a comparable amount of radiation. Its cities have large white houses and wide streets. The world is unified under a single government, headed by a triumvirate which selects a member from each house of the parliament. The three parliamentary houses are divided between the three races of the planet, which although possessing equal rights self-segregate into military and management, law and religion, or research and writing. Its stock exchange is equipped with ropes, ladders, and trapezes that allow the traders to fill the entire volume of the building. For ten points, identify this planet visited by Ulysse Merou in a book by Pierre Boulle. Answer: Le planeete des signes Accept Planet of the Apes 3.