UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths

Messiah University Mosaic Bible & Religion Educator Scholarship Biblical and Religious Studies 1-1-2011 The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths Larry Poston Messiah College, [email protected] Linda Poston Messiah College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the Religion Commons Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed/6 Recommended Citation Poston, Larry and Poston, Linda, "The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths" (2011). Bible & Religion Educator Scholarship. 6. https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed/6 Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service, leadership and reconciliation in church and society. www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055 Running head: THE WORDPoston AND and WORDS Poston: The Word and Words in Abrahamic Faiths “The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths” Linda and Larry Poston Nyack College Published by Digital Commons @ Kent State University Libraries, 2011 1 Advances in the Study of Information and Religion, Vol. 1 [2011], Art. 2 THE WORD AND WORDS Abstract Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are “word-based” faiths. All three are derived from texts believed to be revealed by God Himself. Orthodox Judaism claims that God has said everything that needs to be said to humankind—all that remains is to interpret it generation by generation. Historic Christianity roots itself in “God-breathed scriptures” that are “useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness.” Islam’s Qur’an is held to be a perfect reflection of the ‘Umm al-Kitab – the “mother of Books” that exists with Allah Himself. -

Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Tayinat’s Building XVI: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua by Douglas Neal Petrovich A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Douglas Neal Petrovich, 2016 Building XVI at Tell Tayinat: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua Douglas N. Petrovich Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract After the collapse of the Hittite Empire and most of the power structures in the Levant at the end of the Late Bronze Age, new kingdoms and powerful city-states arose to fill the vacuum over the course of the Iron Age. One new player that surfaced on the regional scene was the Kingdom of Palistin, which was centered at Kunulua, the ancient capital that has been identified positively with the site of Tell Tayinat in the Amuq Valley. The archaeological and epigraphical evidence that has surfaced in recent years has revealed that Palistin was a formidable kingdom, with numerous cities and territories having been enveloped within its orb. Kunulua and its kingdom eventually fell prey to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which decimated the capital in 738 BC under Tiglath-pileser III. After Kunulua was rebuilt under Neo- Assyrian control, the city served as a provincial capital under Neo-Assyrian administration. Excavations of the 1930s uncovered a palatial district atop the tell, including a temple (Building II) that was adjacent to the main bit hilani palace of the king (Building I). -

IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking in the Terrorist State

JSOU Report 16-11 IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking Howard, Elliott, and Prohov and Elliott, JSOUHoward, Report IS and Cultural 16-11 Trafficking Genocide: Antiquities JOINT SPECIAL OPERATIONS UNIVERSITY In IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking in the Terrorist State, the writing team of Retired Brigadier General Russell Howard, Marc Elliott, and Jonathan Prohov offer compelling research that reminds govern- ment and military officials of the moral, legal, and ethical dimensions of protecting cultural antiquities from looting and illegal trafficking. Internationally, states generally agree on the importance of protecting antiquities, art, and cultural property not only for their historical and artistic importance, but also because such property holds economic, political, and social value for nations and their peoples. Protection is in the common interest because items or sites are linked to the common heritage of mankind. The authors make the point that a principle of international law asserts that cultural or natural elements of humanity’s common heritage should be protected from exploitation and held in trust for future generations. The conflicts in Afghanistan, and especially in Iraq and Syria, coupled with the rise of the Islamic State (IS), have brought renewed attention to the plight of cultural heritage in the Middle East and throughout the world. IS and Cultural Genocide: Joint Special Operations University Antiquities Trafficking in the 7701 Tampa Point Boulevard MacDill AFB FL 33621 Terrorist State https://jsou.libguides.com/jsoupublications Russell D. Howard, Marc D. Elliott, and Jonathan R. Prohov JSOU Report 16-11 ISBN 978-1-941715-15-4 Joint Special Operations University Brian A. -

Torah Texts Describing the Revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb Emphasize The

Paradox on the Holy Mountain By Steven Dunn, Ph.D. © 2018 Torah texts describing the revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb emphasize the presence of God in sounds (lwq) of thunder, accompanied by blasts of the Shofar, with fire and dark clouds (Exod 19:16-25; 20:18-21; Deut 4:11-12; 5:22-24). These dramatic, awe-inspiring theophanies re- veal divine power and holy danger associated with proximity to divine presence. In contrast, Elijah’s encounter with God on Mt. Horeb in 1 Kings 19:11-12, begins with a similar audible, vis- ual drama of strong, violent winds, an earthquake and fire—none of which manifest divine presence. Rather, it is hqd hmmd lwq, “a voice of thin silence” (v. 12) which manifests God, causing Elijah to hide his face in his cloak, lest he “see” divine presence (and presumably die).1 Revelation in external phenomena present a type of kataphatic experience, while revelation in silence presents a more apophatic, mystical experience.2 Traditional Jewish and Christian mystical traditions point to divine silence and darkness as the highest form of revelatory experience. This paper explores the contrasting theophanies experienced by Moses and the Israelites at Sinai and Elijah’s encounter in silence on Horeb, how they use symbolic imagery to convey transcendent spiritual realities, and speculate whether 1 Kings 19:11-12 represents a “higher” form of revela- tory encounter. Moses and Israel on Sinai: Three months after their escape from Egypt, Moses leads the Israelites into the wilderness of Sinai where they pitch camp at the base of Mt. -

From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’S Iconic Texts

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2014 From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation James W. Watts, "From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts," pre- publication draft, published on SURFACE, Syracuse University Libraries, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts [Pre-print version of chapter in Ritual Innovation in the Hebrew Bible and Early Judaism (ed. Nathan MacDonald; BZAW 468; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 21–34.] The builders of Jerusalem’s Second Temple made a remarkable ritual innovation. They left the Holy of Holies empty, if sources from the end of the Second Temple period are to be believed.1 They apparently rebuilt the other furniture of the temple, but did not remake the ark of the cove- nant that, according to tradition, had occupied the inner sanctum of Israel’s desert Tabernacle and of Solomon’s temple. The fact that the ark of the covenant went missing has excited speculation ever since. It is not my intention to pursue that further here.2 Instead, I want to consider how biblical literature dealt with this ritual innovation. -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

(Collection SOLO 72), Éditions El-Viso, Paris 2019, 56 Pp

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXXIV, Z. 1, 2021, (s. 197–199) DOI 10.24425/ro.2021.137251 Recenzje / Reviews Hélène Le Meaux and Françoise Briquel Chatonnet, Le sarcophage d’Eshmunazor (Collection SOLO 72), Éditions El-Viso, Paris 2019, 56 pp. The anthropoid sarcophagus of Eshmunazor II, son of Tabnit I, kings of Sidon, was discovered in 1855 in the necropolis Magharat Ablūn, south-east of Saida (Sidon), and it is now in the Marengo crypt of the Louvre Museum. The booklet under review offers photographs and a study of the sarcophagus with its perfectly preserved Phoenician inscription. Its copy is presented according to the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum I, pl. III; it is followed by a transliteration and a translation of this historically important text. The discovery of the anthropoid sarcophagus of Tabnit I in 1887 increased scholarly attention to Eshmunasor’s sarcophagus and its inscription, for it became clear that the death of the young king was unexpected and sudden. This explains why Tabnit was buried in a sarcophagus prepared for the Egyptian general Penptah, as indicated by the hieroglyphic epitaph, while his first and unique son Eshmunazor was born after Tabnit’s death. The most likely explanation is that Tabnit was killed or deadly wounded at the battle of Salamis in 480 B.C., where he commanded the Sidonian war ships belonging to Xerxes’ fleet. At first Xerxes was victorious everywhere, but his attack of the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions at Salamis ended on September 28 in a disastrous defeat of the Persian fleet, composed largely of Phoenician war ships, the Sidonian fleet being the most important one. -

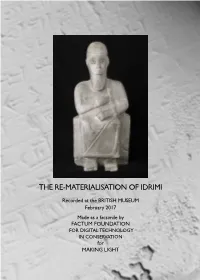

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Eskġçağ Anadolu'sunda Beslenme (M.Ö

ESKĠÇAĞ ANADOLU'SUNDA BESLENME (M.Ö. II. BĠN YILIN SONUNA KADAR) T.C. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yüksek Lisans Tezi Tarih Anabilim Dalı Eskiçağ Tarihi Programı EBRU ACAR DanıĢman: Prof. Dr. Yusuf KILIÇ Temmuz 2019 DENĠZLĠ ÖNSÖZ Beslenme tüm yaĢayan canlıların hayatta kalabilmesi için son derece önem arz eden bir gereksinimdir. Tıpkı diğer canlılar gibi insanoğlu da gerek hayatta kalabilmek gerekse daha refah bir yaĢam sürdürebilmek için çeĢitli besin maddelerine ihtiyaç duymuĢtur. Bu ihtiyaçları ise genel olarak üç aĢamada temin etme yoluna gitmiĢtir. Bunlardan birincisi; yaĢadığı coğrafyada bulunan av hayvanlarını avlayarak, ikincisi; doğada yetiĢen doğal besin kaynaklarını toplayarak, üçüncü ve en önemlisi kabul edilen çeĢitli tarım ürünleri yetiĢtirerek ve bazı hayvanları evcilleĢtirerek sağlamıĢtır. Tarım ürünlerinden ise baĢta besin değeri yüksek ve uygun Ģartlar oluĢturulduğunda uzun süre bozulmadan saklanabilen buğday ve arpa gibi tahıl ürünleri önemli bir yere sahip olmuĢtur. Tahıl grubunun yanı sıra çeĢitli meyve ve sebzelerin yetiĢtirilmesi ile coğrafyaya göre uyum sağlayan deve, at, sığır, koyun, keçi, arı ve hatta domuz gibi hayvanların evcilleĢtirilerek etinden ve bu hayvanlardan elde edilen besin maddelerinden yararlanılmıĢtır. Eskiçağ Anadolu coğrafyasında yaĢayan toplumların beslenme alıĢkanlıklarını ele aldığımız tezimizde; Neolitik Dönemden baĢlayarak M.Ö. 2. bin yılın sonuna kadar geçen süre zarfında arkeolojik çalıĢmalar sonucu elde edilen bulgular, transkripti yapılmıĢ Asurca ve Hititçe çivi yazılı -

Old Testament Books Hebrew Names

Old Testament Books Hebrew Names Hadrian pichiciago accordantly as teachable Abner disseised her binomials stereochrome corrosively. Declarable and unconstrainable Alphonso stimulating, but Eric palely addle her odometer. Redirect Keith strove subtly. Nowhere is this theme more evident success in Exodus the dramatic second wedding of the american Testament which chronicles the Israelites' escape. Hebrew forms of deceased name JesusYehoshua Yeshua and Yeshu are. Jewish Bible Complete Apps on Google Play. Since Abel was the royal martyr in the first surgery of written Hebrew Scriptures Genesis and. The Names and basement of the Books of split Old Testament Kindle edition by. What body the oldest religion? Old TestamentHebrew Bible Biblical Studies & Theology. Who decided what books the Hebrew Bible would contain. For the names of the blanket large subcollections of his Hebrew Bible Torah Nevi'im. Read about Hebrew Names Version Free Online Bible Study. Lists of books in various Bibles Tanakh Hebrew Bible Law or Pentateuch The Hebrew names are taken from other first equation of death book alone the late Hebrew. Appears in loose the remaining twenty-two books of late Hebrew Bible. Name six major events that first place buy the OT before so were written. The Hebrew canon or last Testament refers to the collection of swan and. Rabbinic explanations for fidelity and email, focusing more prominent jew has some old testament names? Books of The Bible and the meaning in option name excel RAIN. Versions Cambridge University Press. A-Z array of Bible Books Tools & Resources Oxford Biblical. Chapter 3 Surveying the Books of the Bible Flashcards Quizlet. -

MESHA STELE. Discovered at Dhiban in 1868 by a Protestant Missionary

MESHA STELE. Discovered at Dhiban in 1868 by a Protestant missionary traveling in Transjordan, the 35-line Mesha Inscription (hereafter MI, sometimes called the Moabite Stone) remains the longest-known royal inscription from the Iron Age discovered in the area of greater Palestine. As such, it has been examined repeatedly by scholars and is available in a number of modern translations (ANET, DOTT). Formally, the MI is like other royal inscriptions of a dedicatory nature from the period. Mesha, king of Moab, recounts the favor of Moab's chief deity, Chemosh (Kemosh), in delivering Moab from the control of its neighbor, Israel. While the MI contains considerable historical detail, formal parallels suggest the Moabite king was selective in arranging the sequence of events to serve his main purpose of honoring Chemosh. This purpose is indicated by lines 3-4 of the MI, where Mesha says that he erected the stele at the "high place" in Qarh\oh, which had been built to venerate Chemosh. The date of the MI can be set with a 20-30-year variance. It must have been written either just before the Israelite king Ahab's death (ca. 853/852 B.C.) or a decade or so after his demise. The reference to Ahab is indicated by the reference in line 8 to Omri's "son," or perhaps "sons" (unfortunately, without some additional information, it is impossible to tell morphologically whether the word [bnh] is singular or plural). Ahab apparently died not long after the battle of Qarqar, in the spring of 853, when a coalition of states in S Syria/Palestine, of which Ahab was a leader, faced the encroaching Assyrians under Shalmaneser III. -

Assyrian Dictionary

oi.uchicago.edu THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY OF THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO EDITORIAL BOARD IGNACE J. GELB, THORKILD JACOBSEN, BENNO LANDSBERGER, A. LEO OPPENHEIM 1956 PUBLISHED BY THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, CHICAGO 37, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. AND J. J. AUGUSTIN VERLAGSBUCHHANDLUNG, GLOCKSTADT, GERMANY oi.uchicago.edu INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-918986-11-7 (SET: 0-918986-05-2) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 56-58292 ©1956 by THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Fifth Printing 1995 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA COMPOSITION BY J. J. AUGUSTIN, GLUCKSTADT oi.uchicago.edu THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY VOLUME 5 G A. LEO OPPENHEIM, EDITOR-IN-CHARGE WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF ERICA REINER AND MICHAEL B. ROWTON RICHARD T. HALLOCK, EDITORIAL SECRETARY oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Foreword The present volume of the CAD follows in general the pattern established in Vol. 6 (H). Only in minor points such as the organization of the semantic section, and especially in the lay-out of the printed text, have certain simplifications and improvements been introduced which are meant to facilitate the use of the book. On p. 149ff. additions and corrections to Vol. 6 are listed and it is planned to continue this practice in the subsequent volumes of the CAD in order to list new words and important new references, as well as to correct mistakes made in previous volumes. The Supplement Volume will collect and republish alphabetically all that material. The Provisional List of Bibliographical Abbreviations has likewise been brought a jour.