At Home in Brownsville: a Plan for Transforming Public Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN GUIDELINES Rehabilitation of NYCHA Residential Buildings

DESIGN GUIDELINES Rehabilitation of NYCHA Residential Buildings 1 DESIGN GUIDELINES Rehabilitation of NYCHA Residential Buildings CONTENTS LETTER FROM NYCHA CHAIR AND CEO SHOLA OLATOYE AND GENERAL MANAGER MICHAEL KELLY INTRODUCTION 6 1 SITE 8 1.1 Site Work 1.2 Site Amenities 1.3 Exterior Lighting 1.4 Parking 1.5 Waste Management 1.6 Erosion and Stormwater Control What Lies Ahead: Green Infrastructure 2 BUILDING EXTERIORS 15 2.1 Facades 2.2 Windows 2.3 Roofs What Lies Ahead: High-performance Building Envelopes 3 BUILDING INTERIORS 20 3.1 Entrances & Lobbies 3.2 Apartment Interiors 3.3 Water Conservation 3.4 Integrated Pest Management 3.5 Kitchen Standards 3.5 Bathroom Standards What Lies Ahead: Water Conservation 4 MECHANICAL, ELECTRICAL & PLUMBING SYSTEMS 27 4.1 Mechanical Systems 4.2 Electrical Systems 4.3 Plumbing Systems What Lies Ahead: Domestic Hot Water (DHW) Systems 5 ELEVATORS 32 6 ACCESSIBILITY 33 APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Letter from NYCHA Chair and CEO Shola Olatoye and General Manager Michael Kelly With the NextGeneration NYCHA 10-year strategic plan, published in May 2015, New York City Housing Authority has laid out a vision of creating safe, clean, and connected communities. In pursuit of this vision, NYCHA seeks to define overarching design principles; create consistent, resident-focused design guidelines; and develop standards and specifications to promote excellence in renovations and new construction so that the next generation of NYCHA will be characterized by design excellence in buildings and on campuses. In so doing, NYCHA will achieve its ultimate goal of creating a better quality of life for residents. -

Happy New Year NYCHA! Page 2 the HOUSING AUTHORITY JOURNAL December 2002 /January 2003

Vol. 33, No. 1 First Class U.S. Postage Paid — Permit No. 4119, New York, N.Y. 10007 December 2002/January 2003 The First-Ever ‘Sounds Of File For The Earned Income Money Available For Resident NYCHA’ Holiday Concert Participation Programs! Tax Credit And he U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Get The Money (HUD) has made over $7 million available to NYCHA res- You’re Owed Tidents for resident participation activities. Household train- ing, new resident orientation, entrepreneurial or job training, ore than 30,000 New workshops and seminars that inform residents about issues and York City Housing Au- operations, and leadership development programs are examples of Mthority (NYCHA) fami- the kinds of activities that will be funded. Generally, programs lies could benefit significantly by that help to empower residents are eligible. filing for the Earned Income Tax “We have to create Citywide programs so that everyone can sit Credit (EITC) this year. The at the table and share in the pie,” said Citywide COP President EITC is a credit for families with Gerri Lamb. “This is an excellent opportunity for resident partic- more than one child earning less ipation. It’s also the first time in many many years that money is than $34,178 a year, families with available for residents to develop programs.” one child earning less than The amount of money available for each Resident Participation $30,201 annually, and individuals Activity Program will reflect the number of authorized dwelling The NYCHA Youth Chorus sang carols and hymns at 24 years of age and older making units covered by the program. -

Eric Adams Message Digital Brooklyn Borough President of the Month Edition

ERIC ADAMS MESSAGE DIGITAL BROOKLYN BOROUGH PRESIDENT OF THE MONTH EDITION BOROUGH PRESIDENT Adams Visits 1 POLICE PlaZA TO CALL FOR UNIFIED command OF OUR laW ENFORCEMENT apparatus AND FOR PERSONAL protection EQUIPMENT FOR ALL POLICE OFFICERS. VIEW MORE INSIDE WWW.BROOKLYN-USA.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2020 (a.) The borough’s current rallying cry, emblazoned at Brooklyn Borough Hall A MESSAGE FROM THE BOROUGH PRESIDENT A “new normal.” That’s what we’re all being told we must conform to as we Brooklynites — New Yorkers, Americans, and citizens of the world — now strive to push through the seemingly unbearable, unthinkable, and impossible in the midst of the devastation of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Without question, life as we now know it is a far cry from the “normal” we knew only a relatively few short weeks ago. The aggressiveness of the virus and the havoc it continues to wreak is unprecedented and unrelenting. And all Brooklynites are united in mourning the incalculable loss of lives, businesses, income, and freedom. The thousands of lost lives that we have been forced to confront, and inconceivable pain we must endure, can never be underestimated and will never be forgotten. But what has been proven over and over again in this borough, in the face of devastation and despair, is that it is the strength, resiliency, courage, and basic humanity of its residents that make #BrooklynStrong. The tragedy left in the wake of this crisis will be felt by all of us for many years to come. However, we can, we must, and we will push through to brighter days on the other side — Click the image to download in support of Brooklyn together, as One Brooklyn. -

Property Management Office

DEVELOPMENT NAME MANAGEMENT OFFICE ADDRESS BOROUGH PHONE 1010 East 178th Street, Bronx, NY 1010 East 178th Street 1010 East 178th Street 10460 Bronx 7185898330 1162-1176 Washington Avenue Claremont Consolidated 1052 Teller Avenue, Bronx, NY 10456 Bronx 7185887411 1090 Rosedale Ave, Bronx, NY 10472- 1471 Watson Avenue SOTOMAYO 6006 Bronx 7188427164 Adams Adams 731 Tinton Avenue, Bronx, NY 10455 Bronx 7189931585 BAILEY AVENUE-WEST 193RD STREET Fort IndePendence 2663 HEATH AVE, BRONX, NY 10463 Bronx 7188846330 Baychester Boston Sector 3570 Bivona Street, Bronx, NY 10475 Bronx 7186712050 160 Saint Anns Avenue, Bronx, NY Betances II, 132 Mill Brook 10454 Bronx 7186650731 225 Alexander Avenue, Bronx, NY Betances II, 182 Mitchel 10454 Bronx 7189930630 160 Saint Anns Avenue, Bronx, NY Betances III, 132 Mill Brook 10454 Bronx 7186650731 225 Alexander Avenue, Bronx, NY Betances III, 182 Mitchel 10454 Bronx 7189930630 2420 Bronxwood Avenue, Bronx, NY Boston Road Plaza Pelham Parkway 10469 Bronx 7185472100 Boston Sector Boston Sector 3570 Bivona Street, Bronx, NY 10475 Bronx 7186712050 DEVELOPMENT NAME MANAGEMENT OFFICE ADDRESS BOROUGH PHONE 1605 East 174th Street, Bronx, NY Boynton Avenue Rehab Bronx River 10472 Bronx 7188429250 1605 East 174th Street, Bronx, NY Bronx River Bronx River 10472 Bronx 7188429250 1605 East 174th Street, Bronx, NY Bronx River Addition Bronx River 10472 Bronx 7188429250 649 Westchester Avenue, Bronx, NY Bronxchester Saint Mary's Park 10455 Bronx 7185851331 998 East 167th Street, Bronx, NY Bryant Avenue-East 174th Street -

Nyc Green Infrastructure 2016 Annual Report

NYC GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Bill de Blasio Mayor Vincent Sapienza Acting Commissioner 0 Table of Contents Introduction………………………….………………………………………………….……………….…………1 Building Organizational Capacity ……………………………….………………………………….….….……..3 Staffing Program Staff and Partner Agency Support ROW Green Infrastructure Maintenance Capital Funding Expense Funding Project Tracking and Data Management Communication Strategies and Educational Activities Regulatory and Rulemaking Activities Citywide Implementation……………………………………………………………………………….…...…….9 Right-of-way Green Infrastructure Standard Designs Public Property Retrofits NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) NYC Department of Education (DOE) NYC Department of Education with the Trust for Public Land (TPL) – Green Infrastructure Playgrounds NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA) NYC Department of Design and Construction (DDC) – Public Buildings Unit Integrated Watershed Planning Green Infrastructure Incentives for Private Property Owners Green Infrastructure Grant Program Expanded Private Incentive Program Planning New Private Incentives Framework 2012 Stormwater Performance Standard Green Infrastructure Program Status Adaptive Management and Lessons Learned……………………………………………………...…..……..19 Program Implementation Challenges and Lessons Learned In the ROW On Public Properties Green Infrastructure Research and Development Program Performance Metrics Report Green Infrastructure Monitoring Permeable Pavement Pilot Project – Local Law 80 of 2013 Exhibits…………………………………………………………………………………………………...……….24 -

Leadership-Prep-Brownsville-2013

Appendix A: Link to the New York State School Report Card Created Thursday, July 24, 2014 Page 1 Charter School Name: 332300860942 LEADERSHIP PREP BROWNSVILLE CS 1. NEW YORK STATE REPORT CARD Provide a direct URL or web link to the most recent New York State School Report Card for the charter school (See https://reportcards.nysed.gov/). (Charter schools completing year one will not yet have a School Report Card or link to one. Please type "URL is not available" in the space provided). http://data.nysed.gov/reportcard.php?year=2013&instid=800000063981 Page 1 Leadership Prep Brownsville CHARTER SCHOOL 2013-14 ACCOUNTABILITY PLAN PROGRESS REPORT Submitted to the SUNY Charter Schools Institute on: September 10, 2014 By Jason Shaad Director of Operations 213 Osborn Street Brooklyn, NY 11212 T: 347 390 0540 F: 718 534 3958 Page 1 of 34 Leadership Prep Brownsville Charter School 2013-14 Accountability Plan Progress Report Page 2 Jason Shaad, Director of Operations, prepared this 2013-14 accountability Progress Report on behalf of the school’s board of trustees: Trustee’s Name Board Position Carrie Abramson Governance Nadine Augusta Trustee Caroline Curry Treasurer, Finance Ben Esner N/A Michael Hall Secretary, Governance John Kim Trustee Matthew Klein N/A Arvind Krishnamurthy Chair (in 2013-14), Finance Tokumbo Shobowale Executive Dyrnest Sinckler Finance Jeff Wetzler Vice Chair, Executive Blonka Winkfield Trustee Julie Jackson N/A Celestina de la Garza has served as principal of the Elementary Academy since 2014. Mark Stulberg has served as principal of the Middle Academy since 2013. Leadership Prep Brownsville Charter School 2013-14 Accountability Plan Progress Report Page 3 INTRODUCTION Organizational Information Leadership Preparatory Brownsville Charter School (Leadership Prep) opened in August of 2009 with 116 students in Kindergarten and First Grade. -

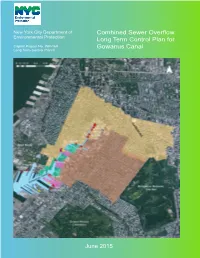

CSO LTCP Gowanus Canal Final LTCP

New York City Department of Combined Sewer Overflow Environmental Protection Long Term Control Plan for Capital Project No. WP-169 Gowanus Canal Long Term Control Plan II June 2015 CSO Long Term Control Plan II Long Term Control Plan Gowanus Canal TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... ES-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Goal Statement ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Regulatory Requirements (Federal, State, Local) ......................................................... 1-2 1.3 LTCP Planning Approach ............................................................................................ 1-4 2.0 WATERSHED/WATERBODY CHARACTERISTICS ...................................................2-1 2.1 Watershed Characteristics ........................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Waterbody Characteristics ......................................................................................... 2-29 3.0 CSO BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ...................................................................3-1 3.1 Collection System Maintenance and Inspection Program ............................................. 3-3 3.2 Maximizing Use of Collection System for Storage ........................................................ 3-3 3.3 -

BROWNSVILLE, BROOKLYN HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT: Evaluating Social Entrepreneurship Programs by Recognizing and Promoting Local Context

Made in Brownsville 2015 BROWNSVILLE, BROOKLYN HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT: Evaluating social entrepreneurship programs by recognizing and promoting local context Rose Jackson, Ernestine Hodges, Sang Cho, Maxine Dotson, and Andrea McCullough pictured above at HIA workshop 1 Made in Brownsville 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Brownsville Health Impact Assessment (HIA) was a collaborative effort between Made in Brownsville, local Brownsville residents, local planning professionals and the parties whose projects are being evaluated. Special thanks go out to the following individuals who dedicated their time, expertise and knowledge to the success of this HIA: Authors Sang Cho Alan Waxman Contributors Quardean Lewis-Allen, Brownsville Resident, Made in Brownsville Maxine Dotson, Brownsville Resident Ernestine Hodges, Brownsville Resident Esmeralda Miller, Brownsville Resident Rose Jackson, Brownsville Resident Diane Waters, Brownsville Resident Lucas Denton, The Melting Pot Community Culinary Center Genese Morgan, Chair, Ocean Hill Resident, Economic Development Committee, CB 16 Andrea McCullough, Brownsville Resident, OHBCYP Brenda Duchene, Brownsville Resident, Ladies of Elegance Tree Williams, Health Bucks Deron Johnston, Center for Court Innovation Erica Mateo, Brownsville Resident, Center for Court Innovation Danny Murphy, Pitkin BID Pernell Brice, Dream Big Foundation Entrepreneurship Lab This research was made possible by a grant from Community Solutions. 2 Made in Brownsville 2015 CONTENTS Executive summary Table of Figures 1.0 Introduction -

Park Avenue Historic District Designation Report April 29, 2014

Park Avenue Historic District Designation Report April 29, 2014 Cover Photograph: Park Avenue, east side north of East 87th Street. Christopher D. Brazee, October 2013 Park Avenue Historic District Designation Report Essay prepared by Matthew A. Postal Building Profiles prepared by Christopher D. Brazee, Jennifer L. Most, and Marianne S. Percival Architects’ Appendix prepared by Marianne S. Percival Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS PARK AVENUE HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP ................................................. FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 PARK AVENUE HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ........................................................... 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 4 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PARK AVENUE HISTORIC DISTRICT ................................................................................................................... 5 Origins of Park Avenue ........................................................................................................... -

New York Housing Agency's Payments to City Are Under Scrutiny

New York Housing Agency’s Payments to City Are Under Scrutiny - N... http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/07/nyregion/07housing.html?pagewan... July 7, 2008 By MANNY FERNANDEZ The biggest landlord in New York City gets one of the biggest bills in New York City. Every year, the city charges it about $200 million, for everything from water to trash pickup to police services. The bill for police protection is twofold: The landlord pays $18 million for basic police, fire and other municipal services, and an additional $65 million for specialized policing. The landlord is not a wealthy private developer, but the New York City Housing Authority, the struggling agency that manages 343 public housing complexes that are home to 406,000 low-income and moderate- income residents. The Housing Authority’s payments to the city have become the focus of new scrutiny in recent weeks, after the agency threatened to close hundreds of community centers, senior centers and resident programs to help close a $170 million budget gap. Tenants, City Council members and advocates for public housing say the payments have contributed to the agency’s financial problems and reflect a double standard in the way the city treats the Housing Authority compared with its treatment of private landlords and other large agencies. “These payments at these times are causing a financial drain to the Housing Authority,” said Councilwoman Rosie Mendez of Manhattan, the chairwoman of the Council’s Public Housing Subcommittee. Last year, the payments to the city rose to $210 million from $208 million in 2006 and $197 million in 2005. -

Latrice Monique Walker

ASSEMBLYWOMAN Latrice Monique Walker Reports to the People • Spring 2018 Dear Neighbor: Happy Spring! As one season draws to a close and another begins, it’s time to recap on what legislation has been passed, this year’s budget, and an update on what to look forward to in the 55th Assembly District. Phase II of Vital Brooklyn has launched, accessing our district to high quality, yet affordable healthcare and housing. This year’s budget awards us with a reinvestment in public education, financial support in the fight against homelessness, and recapitalization in funding for MWBEs. I am ecstatic about all the progress we have made and look forward to all the work that will be completed in order to secure the funding and support we deserve within the 55th Assembly District. This newsletter is intended to be a helpful resource to keep you up to date on issues affecting the 55th As- sembly District, as well as other important information. I also invite you to “like” my Facebook page and follow me on Twitter and Instagram for daily updates from the District and Capitol. Sincerely, Latrice Monique Walker Assemblywoman, 55th A.D. What’s New in the District? VITAL BROOKLYN: PHASE II Vital Brooklyn gives us the opportunity to improve our quality of life from healthcare to housing. This comprehensive approach to help Central Brooklyn gain access to quality community resources is essential for growing the region and empowering the community. Phase II of Vital Brooklyn launches Affordable and Supportive Housing, Economic Development for all over Central Brooklyn with new accessibility to Mobile Green Markets, and Grants Gateway for MWBEs. -

DOI Investigation Leads to Arrest of NYCHA Worker on Charges Of

The City of New York Department of Investigation MARK G. PETERS COMMISSIONER 80 MAIDEN LANE Release #23-2016 NEW YORK, NY 10038 nyc.gov/html/doi 212-825-5900 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: DIANE STRUZZI FRIDAY, JULY 22, 2016 NICOLE TURSO 212-825-5931 DOI INVESTIGATION LEADS TO ARREST OF NYCHA WORKER ON CHARGES OF STEALING AND RESELLING APPLIANCES INTENDED FOR A PUBLIC HOUSING COMPLEX IN BROOKLYN --Investigation also uncovers illegal gambling that results in arrest by NYPD-- Mark G. Peters, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Investigation (“DOI”), today announced the arrest of a NYCHA Caretaker for stealing two new refrigerators and two new stoves purchased by NYCHA and intended for the Seth Low Houses on Powell Street in Brooklyn, and reselling those appliances to a Brooklyn appliance store for $400 in cash. The stolen appliances were valued at a total of approximately $1,690. DOI’s investigation uncovered surveillance video showing the NYCHA employee, KENYON ALLEN, transporting some of the stolen goods in a NYCHA vehicle and in full uniform. As DOI investigated the above theft, it uncovered an illegal gambling operation located in the back of the appliance store, and notified the New York City Police Department (“NYPD”). Police officers arrested the store owner on several misdemeanor gambling charges. The office of Kings County District Attorney Kenneth P. Thompson is prosecuting both of these cases. DOI Commissioner Mark G. Peters said, “NYCHA Caretakers play a critical role in helping to maintain a decent standard of living for our City’s public housing residents. These charges affirm the strong message that stealing City resources – especially those intended for some of the neediest in our community – will not be tolerated.