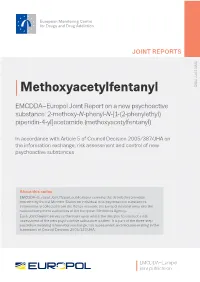

Methoxyacetylfentanyl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and Its Analogues in Biological Specimens

Recommended methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and its Analogues in Biological Specimens MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and its Analogues in Biological Specimens MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2017 Note Operating and experimental conditions are reproduced from the original reference materials, including unpublished methods, validated and used in selected national laboratories as per the list of references. A number of alternative conditions and substitution of named commercial products may provide comparable results in many cases. However, any modification has to be validated before it is integrated into laboratory routines. ST/NAR/53 Original language: English © United Nations, November 2017. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of names of firms and commercial products does not imply the endorse- ment of the United Nations. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Laboratory and Scientific Section of the UNODC (LSS, headed by Dr. Justice Tettey) wishes to express its appreciation and thanks to Dr. Barry Logan, Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, at the Fredric Rieders Family Founda- tion and NMS Labs, United States; Amanda L.A. -

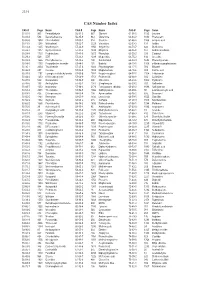

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xh0s7nf Authors Armenian, Patil Vo, Kathy Barr-Walker, Jill et al. Publication Date 2017-10-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review Patil Armenian, Kathy Vo, Jill Barr-Walker, Kara Lynch University of California, San Francisco-Fresno and University of California, San Francisco Keywords: opioid, synthetic opioids, fentanyl, fentanyl analog, carfentanil, naloxone Abbreviations: 4-ANPP: 4-anilino-N-phenethyl-4-piperidine; ANPP 4Cl-iBF: 4-chloroisobutyryfentanyl 4F-iBF: 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl AEI: Advanced electronic information AMF: alpha-methylfentanyl CBP: US Customs and Border Protection CDC: Centers for Disease Control CDSA: Controlled Drug and Substance Act (Canada) CNS: central nervous system DEA: US Drug Enforcement Agency DTO: Drug trafficking organization ED: Emergency department ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay EMCDDA: European Monitoring Centre for Drug and Drug Addiction FDA: US Food and Drug Administration GC-MS: gas chromatography mass spectrometry ICU: intensive care unit IN: intranasal IV: intravenous LC-HRMS: liquid chromatography high resolution mass spectrometry LC-MS/MS: liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry MDA: United Kingdom Misuse of Drugs Act NPF: non-pharmaceutical fentanyl THF-F: tetrahydrofuranfentanyl US: United States USPS: US Postal Service UNODC: United Nations office on drugs and crime 1. Introduction The death rate due to opioid analgesics nearly quadrupled in the US from 1999 to 2011 and was responsible for 33,091 deaths in 2015 (CDC, 2014; Rudd et al., 2016). -

EU EARLY WARNING SYSTEM ADVISORY Fake Oxycodone Tablets

EU EARLY WARNING SYSTEM ADVISORY Fake oxycodone tablets containing brorphine — Slovenia, 2021 RCS ID: EU-EWS-RCS-AD-2021-0001 Issued by: EMCDDA Date issued: 22/01/2021 Transmitted by: Action on New Drugs Sector, EMCDDA Recipients: Early Warning System Network Read with: EU-EWS-RCS-FN-2020-0013 1. Summary and purpose Brorphine is a synthetic opioid monitored by the EMCDDA as a new psychoactive substance. It has been available in Europe since at least March 2020. Its identification has been reported by 4 countries: Belgium, Germany, Slovenia, and Sweden. Similar to other new opioids, brorphine is sold as a replacement to controlled opioids on the surface web, darknet markets, and at street-level. The available information suggests that, similar to fentanyl, brorphine is a potent opioid. Overdose may cause life-threatening poisoning from respiratory depression and arrest. Deaths involving brorphine have been reported in the United States (20 deaths). The purpose of this advisory is to: Highlight a recent identification of two fake oxycodone tablets containing brorphine in Slovenia that were sold on the internet as oxycodone. Highlight that brorphine appears to be a potent opioid that may pose a high risk of life-threatening poisoning. Deaths have been reported in the United States. Request that you report any information you have on brorphine to the EMCDDA as soon as possible so that we can improve our understanding of the potential risks. Information should be reported by email to [email protected] 2. Advisory Background EU-EWS-RCS-AD-2021-0001 Page 1 of 6 Brorphine is a synthetic opioid monitored by the EMCDDA as a new psychoactive substance [1]. -

No Moral Panic: Public Health Responses to Illicit Fentanyls

No Moral Panic: Public Health Responses to Illicit Fentanyls Testimony of Daniel Ciccarone, M.D., M.P.H. Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco Before the House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security United States House of Representatives Hearing: Fentanyl Analogues: Perspectives on Class Scheduling January 28, 2020 Chair Bass, Vice-Chair Demings, Ranking Member Ratcliffe and other distinguished members of the House Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security, thank you very much for the opportunity to testify before you today. It is indeed an honor to be here. My name is Dan Ciccarone. I am professor of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. I have been a clinician for over 30 years and an academic researcher in the area of substance use with a focus on the medical and public health consequences of heroin use for the past 20 years. I have been asked to speak on my perspective on the class scheduling of fentanyl analogues and how these regulations might work counter to the goals of public health. My research and that of my team is multidisciplinary and multi-level. We use the tools of epidemiology, anthropology, statistics, economics, clinical and basic sciences. I am appreciative of my funder, which is the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, as well as my team, which includes Dr. Jay Unick, University of Maryland, Dr. Sarah G. Mars, UCSF, Dr. Dan Rosenblum, Dalhousie University, and Dr. Georgiy Bobashev from RTI, North Carolina. -

OCFENTANIL Critical Review Report Agenda Item 4.5

OCFENTANIL Critical Review Report Agenda Item 4.5 Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Thirty-ninth Meeting Geneva, 6-10 November 2017 39th ECDD (2017) Agenda item 4.5 Ocfentanil Page 2 of 17 39th ECDD (2017) Agenda item 4.5 Ocfentanil Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Substance identification ........................................................................................................... 7 A. International non-proprietary name (INN) ...................................................................................... 7 B. Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) registry number .......................................................................... 7 C. Other names ..................................................................................................................................... 7 D. Trade names ..................................................................................................................................... 7 E. Street names ..................................................................................................................................... 7 F. Physical properties ........................................................................................................................... 7 G. WHO review history ........................................................................................................................ -

Methoxyacetylfentanyl

JOINT REPORTS ISSN 1977-7868 Methoxyacetylfentanyl EMCDDA–Europol Joint Report on a new psychoactive substance: 2-methoxy-N-phenyl-N-[1-(2-phenylethyl) piperidin-4-yl]acetamide (methoxyacetylfentanyl) In accordance with Article 5 of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA on the information exchange, risk assessment and control of new psychoactive substances About this series EMCDDA–Europol Joint Report publications examine the detailed information provided by the EU Member States on individual new psychoactive substances. Information is collected from the Reitox network, the Europol national units and the national competent authorities of the European Medicines Agency. Each Joint Report serves as the basis upon which the decision to conduct a risk assessment of the new psychoactive substance is taken. It is part of the three-step procedure involving information exchange, risk assessment and decision-making in the framework of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. EMCDDA–Europol joint publication I Contents 3 I 1. Introduction 3 I 2. Information collection process 4 I 3. Information required by Article 5.2 of the Council Decision 4 I 3.1 Chemical and physical description, including the names under which the new psychoactive substance is known (Article 5.2(a) of the Council Decision) 6 I 3.2 Information on the frequency, circumstances and/or quantities in which a new psychoactive substance is encountered, and information on the means and methods of manufacture of the new psychoactive substance (Article 5.2(b) of the Council Decision) 6 I 3.2.1 Information -

Determination of Thiafentanil in Plasma Using Lcâ•Fims

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Veterinary Medicine -- Faculty Publications and Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences Other Works 2020 Determination of Thiafentanil in Plasma Using LC–MS Sherry Cox University of Tennessee, Knoxville Joan Bergman University of Tennessee, Knoxville Matthew C. Allender University of Illinois Kimberlee Beckmen Alaska Department of Fish and Game William Lance Wildlife Pharmaceuticals Inc Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_compmedpubs Recommended Citation Cox, Sherry; Bergman, Joan; Allender, Matthew C.; Beckmen, Kimberlee; and Lance, William, "Determination of Thiafentanil in Plasma Using LC–MS" (2020). Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_compmedpubs/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary Medicine -- Faculty Publications and Other Works at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Chromatographic Science, 2020, Vol. 58, No. 1, 1–4 doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmz098 Advance Access Publication Date: 9 December 2019 Article Article Determination of Thiafentanil in Plasma Using LC–MS Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/chromsci/article-abstract/58/1/1/5667452 -

Administration's Information Paper on the Proposed Amendments to the First Schedule to the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance

LC Paper No. CB(2)804/19-20(01) Information Paper Legislative Council Panel on Security Proposed Amendments to the First Schedule to the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance and Schedule 2 to the Control of Chemicals Ordinance PURPOSE This paper briefs Members on the Government’s proposal to – (a) bring five dangerous drugs, namely methoxyacetylfentanyl, FUB-AMB, ADB-FUBINACA, CUMYL-4CN-BINACA and ADB-CHMINACA, under control in the First Schedule to the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance, Cap. 134 (“DDO”); and (b) bring three precursor chemicals, namely APAA, PMK glycidate and PMK glycidic acid, under control in Schedule 2 to the Control of Chemicals Ordinance, Cap. 145 (“CCO”). JUSTIFICATIONS 2. As a regular exercise, the Government has from time to time proposed amendments to the DDO and CCO as appropriate to include new substances under statutory control, having regard to a host of relevant factors, including international control requirements, the uses and harmful effects of the substances, severity of abuse in the local and overseas contexts, advice of the Action Committee Against Narcotics (“ACAN”) and relevant authorities, etc. This is to ensure that law enforcement agencies in Hong Kong could respond effectively to the latest drug developments. Five Dangerous Drugs 3. At the 62nd Session of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (“UNCND”) held in March 2019, Member States adopted the World Health Organisation (“WHO”)’s recommendation to place the following five dangerous drugs under international control. According to the 41st report of the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, the adverse effects of these drugs are as follows – (a) methoxyacetylfentanyl: methoxyacetylfentanyl is a synthetic analogue of fentanyl 1 . -

FOI Summary, Thianil (Thiafentanil Oxalate), MIF 900-000

Date of Index Listing: June 16, 2016 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION SUMMARY ORIGINAL REQUEST FOR ADDITION TO THE INDEX OF LEGALLY MARKETED UNAPPROVED NEW ANIMAL DRUGS FOR MINOR SPECIES MIF 900-000 THIANIL (thiafentanil oxalate) Captive non-food-producing minor species hoof stock “For immobilization of captive minor species hoof stock excluding any member of a food- producing minor species such as deer, elk, or bison and any minor species animal that may become eligible for consumption by humans or food-producing animals.” Requested by: Wildlife Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Freedom of Information Summary MIF 900-000 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION: ............................................................................. 1 II. EFFECTIVENESS AND TARGET ANIMAL SAFETY: .............................................. 1 A. Findings of the Qualified Expert Panel: ...................................................... 2 B. Literature Considered by the Qualified Expert Panel: ................................... 4 III. USER SAFETY: ............................................................................................. 6 IV. AGENCY CONCLUSIONS: .............................................................................. 7 A. Determination of Eligibility for Indexing: .................................................... 7 B. Qualified Expert Panel: ............................................................................ 7 C. Marketing Status: ................................................................................... 7 D. Exclusivity: -

Methoxyacetylfentanyl Science for a Safer World

Designer Fentanyls Drugs that kill and how to detect them Methoxyacetylfentanyl Science for a safer world The in vitro metabolism of methoxyacetylfentanyl Simon Hudson & Charlotte Cutler, laboratories working for UK coroners. Sport and Specialised Analytical This includes testing for synthetic This paper is intended to Services. LGC Standards, cannabinoid receptor agonists, other share knowledge from LGC’s Fordham, UK. new psychoactive substances (NPS), laboratories regarding: drugs of abuse and prescription Recent communications from the drugs. The technology used is 1. Analytical methodology enabling European Monitoring Centre for Thermo Scientific™ Orbitrap™- the detection of low levels of many Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) based high-resolution accurate-mass drugs including fentanyl analogues have highlighted a growing trend in (HRAM) liquid chromatography- 2. Methoxyacetylfentanyl in vitro the seizures and recreational use of mass spectrometry (LCMS) enabling metabolism data. fentanyl analogues in certain European extremely broad analyte coverage at countries. As with New Psychoactive high sensitivity. Substances (NPS), the fentanyl methoxyacetylfentanyl analogues in circulation are constantly To maintain the efficacy of our drug evolving with nine substances reported testing service it is imperative that for the first time in 2016 and ten in the metabolic fate of new drug 2017. There has been a large increase compounds such as the fentanyl in availability of these drugs in Europe analogues is considered. As raw drug in the past few years due to their open material becomes available, either sale by chemical companies based from casework or from purchases, A rapid in vitro analysis on both substances in China. In Europe they are typically a rapid in vitro metabolism technique was performed as follows: used as ‘legal’ substitutes for heroin is employed to generate data for and other illicit opioids. -

Fentanyl and Heroin-Related Deaths in North Carolina Alison Miller, MA and Ruth Winecker, Phd, F-ABFT

Fentanyl and Heroin-Related Deaths in North Carolina Alison Miller, MA and Ruth Winecker, PhD, F-ABFT OVERVIEW The North Carolina Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (NC OCME) investigates all sudden, unexpected, and violent deaths in North Carolina, including all suspected drug-related or poisoning deaths, and oversees the operations of the state’s entire medical examiner system. The NC OCME collects data from autopsy reports, death certificates, investigation reports, and toxicology reports on all deaths investigated by the medical examiner system in North Carolina. The data collected by the NC OCME can be used to identify trends relating to deaths in North Carolina, inform public health initiatives, and develop prevention strategies. NC OCME TOXICOLOGY LABORATORY The NC OCME Toxicology Laboratory is accredited by the American Board of Forensic Toxicology (ABFT) and performs toxicology testing on all drug-related deaths in North Carolina to assist the pathologist in determining cause and manner of death. The NC OCME Toxicology Laboratory screens for more than 600 compounds. The number of novel compounds detected during screening has risen dramatically in the last several years. HEROIN-RELATED DEATHS IN NORTH CAROLINA Deaths involving heroin increased by 1119.1% from 2010 to 2016. It is important to note that the NC OCME Toxicology Laboratory revised testing procedures for heroin in 2017, providing a more accurate representation of the involvement of this drug in poisoning deaths. Figure 1 Poisoning Deaths Involving Heroin in North Carolina, 2010 – 2017* 700 6.0 Heroin 5.6 Rate per 100,000 600 5.0 4.0 500 4.0 400 2.9 3.0 300 2.0 573 1.7 483 2.0 200 401 0.9 287 0.5 1.0 100 170 201 47 87 0 0.0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017* 1 | Page *2017 data are considered provisional and subject to change as cases continue to be finalized.