Jess Gagliardi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

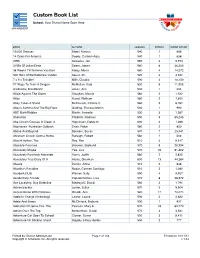

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

Defining the Role of First Lady

- Defining the Role of First Lady An Honors College Thesis (Honors 499) By Denise Jutte - Thesis Advisor Larry Markle Ball State University Muncie, IN Graduation Date: May 3, 2008 ;' l/,~· ,~, • .L-',:: J,I Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction: Defining the Role of First Lady 4 First Ladies Ranking 11 Individual Analysis of First Ladies 12 Chronological Order Observations on Leadership and Comparisons to Previous Presidential Rankings 177 Conclusion: The Role ofthe Future First Spouse 180 Works Cited 182 Appendix A: Ranking of Presidents 183 Appendix B: Presidential Analysis 184 Appendix C: Other Polls and Rankings of the First Ladies 232 1 Abstract In the Fall Semester of 2006, I took an honors colloquium taught by Larry Markle on the presidents of the United States. Throughout the semester we studied all of the past presidents and compiled a ranked list of these men based on our personal opinion of their greatness. My thesis is a similar study of their wives. The knowledge I have gained through researching presidential spouses has been very complementary to the information I learned previously in Mr. Markle's class and has expanded my understanding of one ofthe most important political positions in the United States. The opportunity to see what parallels developed between my ran kings of the preSidents and the women that stood behind them has led me to a deeper understanding ofthe traits and characteristics that are embodied by those viewed as great leaders. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dad for helping me to participate in and understand the importance of history and education at a young age. -

23 Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison

First Ladies of America Showing a dignified, even solemn Continuing to put her house countenance, the portraits of Caroline in order, she also cataloged “Carrie” Harrison belie her spirit and personality. the White House china, Warm, sentimental and artistic by nature, she designed a cabinet to hold the was fun loving, easily amused and quick to historical collection, and added to it by forgive. designing her own china for the White House. The daughter of parents who were both educators, she taught school in Kentucky for a year before Mrs. Harrison also changed the atmosphere inside the returning home at age 21 to marry Benjamin mansion. She put up the first White House Christmas Harrison, the grandson of President William Henry tree, and for the first time since 1845, a first lady’s Harrison. guests were invited to dance. As her husband’s law career advanced and he Mrs. Harrison’s interests were not all domestic. The became increasingly more focused on politics, Mrs. first President General of the Daughters of the American Harrison cared for their children, often alone, and Revolution, she kept the organization intact during its missed his presence in their family’s life. Tension founding, and she worked to advance the rights of developed in the marriage. American women. Ironically perhaps, it was Harrison’s extended When asked to support the construction of a absence during the Civil War that brought new wing at Johns Hopkins Hospital, she them back together. When Harrison Benjamin agreed — but not until hospital officials returned home safely after commanding agreed to admit women to their medical Union forces in some of the worst Harrison school. -

22 and 24 Frances Folsom Cleveland

First Ladies of America When Grover Cleveland married Actively involved in local Frances Folsom in 1886, he was 27 years charities for African-American her senior and old enough to be her father. children, Mrs. Cleveland was also a firm supporter of education A friend of her family and partner in her father’s for women. She served on the board law firm, Cleveland had known Frances since the of trustees for her alma mater, Wells day she was born. He was a presence in her life as College, and was instrumental in a campaign that led she grew up; upon her father’s death, when she was to the establishment of the New Jersey College for 11-years-old, Cleveland took over the administration Women. of her father’s estate and become her unofficial guardian. At the White House, she was a gracious hostess who planned regular receptions on Saturdays so that Affectionately known as “Frankie” during her working-class women could attend. Wherever she childhood, Mrs. Cleveland was born in Buffalo, N.Y., went, her youth, charm and charisma drew crowds of as the Civil War was drawing to a close. enthusiastic and devoted admirers. She received a well-rounded education, topping off So popular was Mrs. Cleveland, in fact, that the her grammar and high school years with unauthorized use of her image to sell products enrollment at Wells College, one of the first became the target of legislation aimed at liberal arts schools for women in the country. Grover preventing such unscrupulous business practices. The measure never passed, but While there, she studied astronomy, Cleveland it did foreshadow problems future first botany, and political science, and Administration, ladies would experience from an overly enjoyed activities including debate 1855-1889 & enthusiastic public. -

Dolley Madison

Life Story Dolley Madison 1768–1849 expulsion from Quaker Meeting, and his wife took in boarders to make ends meet . Perhaps pressured by her father, who died shortly after, Dolley, at 22, married Quaker lawyer John Todd, whom she had once rejected . Her 11-year- old sister, Anna, lived with them . The Todds’ first son, called Payne, was born in 1791, and a second son, William, followed in 1793 . In the late summer of that year, yellow fever hit Philadelphia, and before cold weather ended the epidemic, Dolley lost four members of her family: her father-in-law, her mother-in-law, and then, on the same October day, her husband and three-month-old William . She wrote a half-finished sentence in a letter: “I am now so unwell that I can’t . ”. James Sharples Sr ., Dolley Madison, ca . 1796–1797 . Pastel on paper . Independence National Historic Park, Philadelphia . Added to her grief, Dolley faced an financial strain at the same time . Fifty extremely difficult situation . She was years later, she would face them again . a widow caring for her small son and her young sister . Men were considered Dolley’s mother went to live with a responsible for their female relatives; it was married daughter, and Dolley, Payne, one of the social side effects of coverture and Anna moved back to the family (see Resource 1) . But all the men who might home . Philadelphia was then the nation’s have cared for Dolley were gone . Her temporary capital and most sophisticated husband had left her some money in his city . -

Team Players: Triumph and Tribulation on the Campaign Trail

residential campaigns that celebrate our freedom to choose a leader by election of the people are events P unique to our country. It is an expectant, exciting time – a promise kept by the Constitution for a better future. Rituals developed over time and became traditions of presidential hopefuls – the campaign slogans and songs, hundreds of speeches, thousands of handshakes, the countless miles of travel across the country to meet voters - all reported by the ever-present media. The candidate must do a balancing act as leader and entertainer to influence the American voters. Today the potential first spouse is expected to be involved in campaign issues, and her activities are as closely scrutinized as the candidate’s. However, these women haven’t always been an official part of the ritual contest. Campaigning for her husband’s run for the presidency is one of the biggest self-sacrifices a First Lady want-to-be can make. The commitment to the campaign and the road to election night are simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting. In the early social norms of this country, the political activities of a candidate’s wife were limited. Nineteenth-century wives could host public parties and accept social invitations. She might wave a handkerchief from a window during a “hurrah parade” or quietly listen to a campaign speech behind a closed door. She could delight the crowd by sending them a winsome smile from the front porch campaign of her own home. But she could not openly show knowledge of politics and she could not vote. As the wife of a newly-elected president, her media coverage consisted of the description of the lovely gown she wore to the Inaugural Ball. -

The President Woodrow Wilson House Is a National Historic Landmark and House Museum

Autumn Newsletter 2013 The President Woodrow Wilson House is a national historic landmark and house museum. The museum promotes a greater awareness of President Wilson’s public life and ideals for future generations through guided tours, exhibitions and educational programs. Above photo: Back garden evening party at The President Woodrow Wilson House. The museum also serves as a community CELEBRATING THE PRESIDENT’S Woodrow Wilson’s legacy, preservation model and resource, dedicated to one hundred years later the stewardship and CENTENNIAL presentation of an Why should anyone care about the President Wilson revived the practice, authentic collection and President Woodrow Wilson House? abandoned for more than a century, of the property. That is a fair question to consider in President delivering the State of the Union 2013, the first of eight years marking the message in person before Congress. He centennial of President Wilson’s term in regularly appeared at the Capitol to The President office, 1913–1921. promote his legislative initiatives. In a Woodrow Wilson “President Wilson imagined the world recent interview, WILSON biographer A. House is a property of at peace and proposed a plan to achieve Scott Berg noted, “There's a room in the National Trust that vision,” answers Robert A. Enholm, Congress called the President's Room. No for Historic executive director of the Woodrow Wilson president has used it since Woodrow Preservation, a House in Washington, D.C. “The Wilson. No president used it before privately funded, non- challenge he issued almost a century ago Woodrow Wilson. He used it regularly.” profit corporation, remains largely unanswered today.” Before President Wilson the national helping people protect, During this centennial period, the government played a smaller role in the enhance and enjoy the Woodrow Wilson House will be developing everyday lives of Americans than is true places that matter to exhibitions and programs to explore the today. -

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

White House Photographs May 8, 1976

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Photographs May 8, 1976 This database was created by Library staff and indexes all photographs taken by the Ford White House photographersrelated to this subject. Use the search capabilities in your PDF reader to locate key words within this index. Please note that clicking on the link in the “Roll #” field will display a 200 dpi JPEG image of the contact sheet (1:1 images of the 35 mm negatives). Gerald Ford is always abbreviated “GRF” in the "Names" field. If the "Geographic" field is blank, the photo was taken within the White House complex. The date on the contact sheet image is the date the roll of film was processed, not the date the photographs were taken. All photographs taken by the White House photographers are in the public domain and reproductions (600 dpi scans or photographic prints) of individual images may be purchased and used without copyright restriction. Please include the roll and frame numbers when contacting the Library staff about a specific photo (e.g., A1422-10). To view photo listings for other dates, to learn more about this project or other Library holdings, or to contact an archivist, please visit the White House Photographic Collection page View President Ford's Daily Diary (activities log) for this day Roll # Frames Tone Subject - Proper Subject - Generic Names Geographic Location Photographer A9656 7A-11A BW SecState Trip to Africa-SecState Returns from 6- standing on tarmac, in front Kissinger, Nancy Kissinger, Others, Andrews Air Force Andrews Air Thomas Nation African Tour-Airport Arrival; Chief of plane; Catto and Kissinger Military Officers, Catto Base, MD Force Base Protocol Officer Henry Catto standiang together; aircraft in background A9657 26-36 BW SecState Trip to Africa-SecState Returns from 6- HAK kissing wife; Kissinger, Nancy Kissinger, Sen. -

Rosalynn Carter

A t Ja me s M ad i son Un i ve rs i ty Rosalynn Carter Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter has worked for more than three decades to improve the quality of life for people around the world. Today, she is an advocate for mental health, early childhood immunization, human rights, and conflict resolution through her work at The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia. The Center is a private, not-for-profit institution founded by former President and Mrs. Jimmy Carter in 1982. A full partner with the president in all the Center’s activities, the former first lady is a member of The Carter Center Board of Trustees. She created and chairs The Carter Center’s Mental Health Task Force, an advisory body of experts, consumers, and advocates promoting positive change in the mental health field. Each year, she hosts the Rosalynn Carter Symposium on Mental Health Policy, bringing together leaders of the nation’s mental health organizations to address critical issues. Mrs. Carter emerged as a driving force for mental health when, during the Carter administration, she became active honorary chair of the President’s Commission on Mental Health, which resulted in passage of the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980. She served on the Policy Advisory Board of The Atlanta Project (TAP), a program of The Carter Center addressing the social ills associated with poverty and quality of life citywide, from the program’s inception in 1991, until its transfer to Georgia State University in 1999. In 1988, she convened with three other former first ladies the “Women and the Constitution” conference at The Carter Center to assess that document’s impact on women.