Chapter 4: Island and Mainland: Toward a Pan-European Style I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

Music in the Mid-Fifteenth Century 1440–1480

21M.220 Fall 2010 Class 13 BRIDGE 2: THE RENAISSANCE PART 1: THE MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY 1. THE ARMED MAN! 2. Papers and revisions 3. The (possible?) English Influence a. Martin le Franc ca. 1440 and the contenance angloise b. What does it mean? c. 6–3 sonorities, or how to make fauxbourdon d. Dunstaple (Dunstable) (ca. 1390–1453) as new creator 4. Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) (ca. 1397–1474) and his music a. Roughly 100 years after Guillaume de Machaut b. Isorhythmic motets i. Often called anachronistic, but only from the French standpoint ii. Nuper rosarum flores iii. Dedication of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de’ Fiore in Florence iv. Structure of the motet is the structure of the cathedral in Florence v. IS IT? Let’s find out! (Tape measures) c. Polyphonic Mass Cycle i. First flowering—Mass of Machaut is almost a fluke! ii. Cycle: Five movements from the ordinary, unified somehow iii. Unification via preexisting materials: several types: 1. Contrafactum: new text, old music 2. Parody: take a secular song and reuse bits here and there (Zachara) 3. Cantus Firmus: use a monophonic song (or chant) and make it the tenor (now the second voice from the bottom) in very slow note values 4. Paraphrase: use a song or chant at full speed but change it as need be. iv. Du Fay’s cantus firmus Masses 1. From late in his life 2. Missa L’homme armé a. based on a monophonic song of unknown origin and unknown meaning b. Possibly related to the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded in 1430. -

Josquin Des Prez: Master of the Notes

James John Artistic Director P RESENTS Josquin des Prez: Master of the Notes Friday, March 4, 2016, 8 pm Sunday, March 6, 2016, 3pm St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM CERDDORION Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Gaude Virgo Mater Christi Anna Harmon Jamie Carrillo Ralph Bonheim Peter Cobb From “Missa de ‘Beata Virgine’” Erin Lanigan Judith Cobb Stephen Bonime James Crowell Kyrie Jennifer Oates Clare Detko Frank Kamai Jonathan Miller Gloria Jeanette Rodriguez Linnea Johnson Michael Klitsch Michael J. Plant Ellen Schorr Cathy Markoff Christopher Ryan Dean Rainey Praeter Rerum Seriem Myrna Nachman Richard Tucker Tom Reingold From “Missa ‘Pange Lingua’” Ron Scheff Credo Larry Sutter Intermission Ave Maria From “Missa ‘Hercules Dux Ferrarie’” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sanctus President Ellen Schorr Treasurer Peter Cobb Secretary Jeanette Rodriguez Inviolata Directors Jamie Carrillo Dean Rainey From “Missa Sexti toni L’homme armé’” Michael Klitsch Tom Reingold Agnus Dei III Comment peut avoir joye The members of Cerddorion are grateful to James Kennerley and the Church of Saint Ignatius of Petite Camusette Antioch for providing rehearsal and performance space for this season. Jennifer Oates, soprano; Jamie Carillo, alto; Thanks to Vince Peterson and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for providing a performance space Chris Ryan, Ralph Bonheim, tenors; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses for this season. Thanks to Cathy Markoff for her publicity efforts. Mille regretz Allégez moy Jennifer Oates, Jeanette Rodriguez, sopranos; Jamie Carillo, alto; PROGRAM CREDITS: Ralph Bonheim, tenor; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses Myrna Nachman wrote the program notes. -

A History of British Music Vol 1

A History of Music in the British Isles Volume 1 A History of Music in the British Isles Other books from e Letterworth Press by Laurence Bristow-Smith e second volume of A History of Music in the British Isles: Volume 1 Empire and Aerwards and Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History From Monks to Merchants Laurence Bristow-Smith The Letterworth Press Published in Switzerland by the Letterworth Press http://www.eLetterworthPress.org Printed by Ingram Spark To © Laurence Bristow-Smith 2017 Peter Winnington editor and friend for forty years ISBN 978-2-9700654-6-3 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Contents Acknowledgements xi Preface xiii 1 Very Early Music 1 2 Romans, Druids, and Bards 6 3 Anglo-Saxons, Celts, and Harps 3 4 Augustine, Plainsong, and Vikings 16 5 Organum, Notation, and Organs 21 6 Normans, Cathedrals, and Giraldus Cambrensis 26 7 e Chapel Royal, Medieval Lyrics, and the Waits 31 8 Minstrels, Troubadours, and Courtly Love 37 9 e Morris, and the Ballad 44 10 Music, Science, and Politics 50 11 Dunstable, and la Contenance Angloise 53 12 e Eton Choirbook, and the Early Tudors 58 13 Pre-Reformation Ireland, Wales, and Scotland 66 14 Robert Carver, and the Scottish Reformation 70 15 e English Reformation, Merbecke, and Tye 75 16 John Taverner 82 17 John Sheppard 87 18 omas Tallis 91 19 Early Byrd 101 20 Catholic Byrd 108 21 Madrigals 114 22 e Waits, and the eatre 124 23 Folk Music, Ravenscro, and Ballads 130 24 e English Ayre, and omas Campion 136 25 John Dowland 143 26 King James, King Charles, and the Masque 153 27 Orlando Gibbons 162 28 omas -

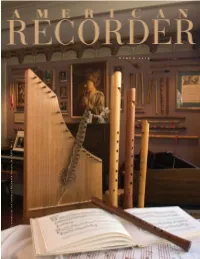

M a R C H 2 0

march 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Order your recorder discs through the ARS CD Club! The ARS CD Club makes hard-to-find or limited release CDs by ARS members available to ARS members at the special price listed (non-members slightly higher). Add Shipping and Handling:: $2 for one CD, $1 for each additional CD. An updated listing of all available CDs may be found at the ARS web site: <www.americanrecorder.org>. NEW LISTING! ____THE GREAT MR. HANDEL Carolina Baroque, ____LUDWIG SENFL Farallon Recorder Quartet Dale Higbee, recorders. Sacred and secular music featuring Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, Louise by Handel. Live recording. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____HANDEL: THE ITALIAN YEARS Elissa Carslake and Hanneke van Proosdij. 23 lieder, ____SOLO, Berardi, recorder & Baroque flute; Philomel motets and instrumental works of the German DOUBLE & Baroque Orchestra. Handel, Nel dolce dell’oblio & Renaissance composer. TRIPLE CONCER- Tra le fiamme, two important pieces for obbligato TOS OF BACH & TELEMANN recorder & soprano; Telemann, Trio in F; Vivaldi, IN STOCK (Partial listing) Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee, recorders. All’ombra di sospetto. Dorian. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____ARCHIPELAGO Alison Melville, recorder & 2-CD set, recorded live. $24 ARS/$28 others. traverso. Sonatas & concerti by Hotteterre, Stanley, ____JOURNEY Wood’N’Flutes, Vicki Boeckman, ____SONGS IN THE GROUND Cléa Galhano, Bach, Boismortier and others. $15 ARS/$17 Others. Gertie Johnsson & Pia Brinch Jensen, recorders. recorder, Vivian Montgomery, harpsichord. Songs ____ARLECCHINO: SONATAS AND BALLETTI Works by Dufay, Machaut, Henry VIII, Mogens based on grounds by Pandolfi, Belanzanni, Vitali, OF J. -

Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European Musical

Ch. 4: Island and Mainland: Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European musical style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries moved from distinct national styles (particularly of the Ars nova and Trecento) toward a more unified, international style. II. English Music and Its Influence A. Fragmentary Remains 1. English music had a style that was distinct from continental music of the Middle Ages. 2. English singers included the third among the consonant intervals. 3. The Thomas gemma Cantuariae/Thomas caesus in Doveria (Ex. 4-3) includes many features associated with English music, such as almost equal ranges in the top two parts and frequent voice exchanges. B. Kings and the Fortunes of War 1. The Old Hall Manuscript contains the earliest English polyphonic church music that can be read today. 2. Copied for a member of the royal family, most of its contents belong to the Mass Ordinary. 3. Henry V, who is associated with the Old Hall Manuscript, holds a prominent place in history of this period. 4. When Henry’s army occupied part of northern France in the early fifteenth century, his brother John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, was in charge. This brother included the composer John Dunstable (ca. 1390–1453) among those who received part of his estates when he died. 5. Dunstable’s music influenced continental composers. C. Dunstable and the “Contenance Angloise” 1. Dunstable’s arrival in Paris caused the major composers to follow his style, known as la contenance angloise. a. Major-mode tonality b. Triadic harmony c. Smooth handling of dissonance 2. -

The Tallis Scholars

Friday, April 10, 2015, 8pm First Congregational Church The Tallis Scholars Peter Phillips, director Soprano Alto Tenor Amy Haworth Caroline Trevor Christopher Watson Emma Walshe Clare Wilkinson Simon Wall Emily Atkinson Bass Ruth Provost Tim Scott Whiteley Rob Macdonald PROGRAM Josquin Des Prez (ca. 1450/1455–1521) Gaude virgo Josquin Missa Pange lingua Kyrie Gloria Credo Santus Benedictus Agnus Dei INTERMISSION William Byrd (ca. 1543–1623) Cunctis diebus Nico Muhly (b. 1981) Recordare, domine (2013) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) Tribute to Caesar (1997) Byrd Diliges dominum Byrd Tribue, domine Cal Performances’ 2014–2015 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 26 CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES he end of all our exploring will be Josquin, who built on the cantus firmus tradi- Tto arrive where we started and know the tion of the 15th century, developing the freer place for the first time.” So writes T. S. Eliot in parody and paraphrase mass techniques. A cel- his Four Quartets, and so it is with tonight’s ebrated example of the latter, the Missa Pange concert. A program of cycles and circles, of Lingua treats its plainsong hymn with great revisions and reinventions, this evening’s flexibility, often quoting more directly from performance finds history repeating in works it at the start of a movement—as we see here from the Renaissance and the present day. in opening soprano line of the Gloria—before Setting the music of William Byrd against moving into much more loosely developmen- Nico Muhly, the expressive beauty of Josquin tal counterpoint. Also of note is the equality of against the ascetic restraint of Arvo Pärt, the imitative (often canonic) vocal lines, and exposes the common musical fabric of two the textural variety Josquin creates with so few ages, exploring the long shadow cast by the voices, only rarely bringing all four together. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century

David Fallows Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century VARIORUM 1996 CONTENTS Preface vn Acknowledgements V1H ENGLAND English song repertories of the mid-fifteenth century 61-79 Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 103. London, 1976-77 II Robertus de Anglia and the Oporto song collection 99-128 Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music: A Memorial Volume to Thurston Dart, ed. Ian Bent. London: Stabler & Bell Ltd, 1981 III Review of Julia Boffey: Manuscripts of English Courtly Love Lyrics in the later Middle Ages 132-138 Journal of the Royal Musical Association 112. Oxford, 1987 IV Dunstable, Bedyngham and O rosa be I la 287-305 The Journal of Musicology 12. Berkeley, Calif, 1994 MAINLAND EUROPE The contenance angloise: English influence on continental composers of the fifteenth century 189-208 Renaissance Studies 1. Oxford, 1987 VI French as a courtly language in fifteenth-century Italy: the musical evidence 429-441 Renaissance Studies 3. Oxford, 1989 VI VII A glimpse of the lost years: Spanish polyphonic song, 1450-70 19-36 New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern, ed. Josephine Wright with Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music. Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1992 VIII Polyphonic song in the Florence of Lorenzo's youth, ossia: the provenance of the manuscript Berlin 78.C.28: Naples or Florence? 47-61 La musica a Firenze at tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, ed. Piero Gargiulo. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1993 IX Prenez sur moy: Okeghem's tonal pun 63-75 Plainsong and Medieval Music 1. -

A Conversation with Josquin

A Conversation and a skip later I found myself face to face with a rural to spot, sometimes extremely difficult, in various keys, once more. policemen, who looked perfectly ridiculous in a red with added rests…but the whole thing is always there, “Maurice, this is very good, you’ve done the work of an with Josquin and gold uniform and towering kepi. like in the superius of the Gloria and the “complaint honest artisan. You’ve written in the Franco-Flemish “Your music, please!” machines” in the bass of the Agnus 2.” style, and done the best you could with what you Those bright and beady eyes…why, yes, they were Josquin bent over the score, more and more interested: have.” In the church of Sainte Croix Vallée-Française, I was Josquin’s! He was actually there, and easily recognizable “This notation is wonderful, with the four voices one He winked and slipped away. about to give the starting pitch for the eleven singers in in his high green stockings. And he was obviously very above the other. In my day, we had to count the beats I opened my eyes. My scores were before me, and there the Métamorphoses and Biscantor! ensembles. cross. and really pay attention. When it’s printed like this, were the singers, waiting patiently. The pitch pipe I closed my eyes for a second… “What’s this Chascun me crie ...même Hercule! mass? you can take it easy…even have a snooze from time sounded an “A” and the first notes of the Kyrie from …and when I opened them again…my binder was I never wrote such a thing!” to time!” Hercules could finally plunge me into a marvelous empty! My music had disappeared! My tools, my “Calm down, Josquin…You and a lot of other people And then with great enthusiasm: fountain of youth. -

The University of Oklahoma Graduate College A

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S RESOURCE GUIDE TO THE OFFICE OF COMPLINE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By D. JASON BISHOP Norman, Oklahoma 2006 UMI Number: 3239542 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3239542 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 A CONDUCTOR’S RESOURCE GUIDE TO THE OFFICE OF COMPLINE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Dennis Shrock, Major Professor Dr. Irvin Wagner, Chair Dr. Sanna Pederson, Co-Chair Dr. Roland Barrett Dr. Steven Curtis Dr. Marilyn Ogilvie ' Copyright by D. JASON BISHOP 2006 All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction Purpose of the Study 1 Need for the Study 2 Survey of Related Literature 3 Scope & Limitations of the Study, -

Introduction to Instalment 5

547 INTRODUCTION TO INSTALMENT 5 This fifth instalment of the Trent 91 edition highlights a particular batch of works which I am certainly not the first to notice. Most (if not absolutely all) of them seem to have some connection with Johannes Martini, and a large proportion of them may be his work. Martini seems typical amongst medieval and Renaissance musicians of renown in that we only know about part of his career. His formative years (probably in the 1460’s) remain obscure. Likewise we have little music by Dunstable which seems to be later than ca. 1430, and probably equally little from the later years of Ockeghem, Binchois and Regis. Ockeghem’s younger years also seem to be poorly documented. One or two of the pieces included here are almost certain to be Martini’s. The longer version of the Missa Cucu in Trent 91 may predate the shortened Cucu Kyrie in ModC. Likewise the two motets Flos virginum and Jhesu Christe piissime are contrafact sections of Martini’s Missa Coda di pavon which have been musically revised and which share similar sources for their new texts (both texts are by Petrarch). Since Jhesu Christe piissime has added material which is similar to passages in other Martini pieces, it is hard to see how anybody except the composer could have been responsible for this revision. Likewise the wedding motet Perfunde celi rore is probably Martini’s since it is similar to later music by him, and also because it was produced for his Ferrara patron at approximately the outset of Martini’s career there.