Ancient Chinese Science and the Teaching of Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Chinese Learning College Collection: Dream Pool Essays

Chinese Learning College Collection: Dream Pool Essays (Youth Edition)(Chinese Edition) \ PDF \ GIAIAMYFJS Ch inese Learning College Collection: Dream Pool Essays (Y outh Edition)(Ch inese Edition) By BEI SONG ) SHEN KUO paperback. Condition: New. Ship out in 2 business day, And Fast shipping, Free Tracking number will be provided after the shipment.Paperback. Pub Date: 2012 Pages: 279 Language: Chinese Publisher: Hubei Fine Arts Publishing House National College Collection: Dream Pool Essays (Youth Edition) Shen Kuo set various studies in one of the masterpiece. a book about 1086 to 1093. including three parts of writing. fill the conversation by writing. continued writing . a total of 609. Covering astronomy. calendar. weather. geology. geography. physics. chemistry. biology. agriculture. water conservancy. construction. medicine. history. literature. art. personnel. military. legal and many other areas. Such information has important reference value for studying the Northern Song Dynasty social. political. technological. economic aspects. Xu Lang written in this book excerpt wonderful. and with reference to the results of other collation. be the translation of comments. Contents: Volume I story one dressed degree of contention the Huai hall orpiment change the word Volume II Story Two cases of cervical granted South Course Officer Volume III. a Jun Stone. dialectical Stone Yang Sui illuminated object state solution salt marshes no fixed river sand vanilla steel-making provision of beetle wine the Po Lo Weights and Measures papers dialectical two the... READ ONLINE [ 1.17 MB ] Reviews A whole new e book with a new point of view. This is certainly for all those who statte there had not been a well worth looking at. -

Mohist Theoretic System: the Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections with the Universal Values and Global Sustainability

Cultural and Religious Studies, March 2020, Vol. 8, No. 3, 178-186 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.03.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Mohist Theoretic System: The Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections With the Universal Values and Global Sustainability SONG Jinzhou East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Mohism was established in the Warring State period for two centuries and half. It is the third biggest schools following Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi (468 B.C.-376 B.C.) was the first major intellectual rivalry to Confucianism and he was taken as the second biggest philosophy in his times. However, Mohism is seldom studied during more than 2,000 years from Han dynasty to the middle Qing dynasty due to his opposition claims to the dominant Confucian ideology. In this article, the author tries to illustrate the three potential functions of Mohism: First, the critical/revision function of dominant Confucianism ethics which has DNA functions of Chinese culture even in current China; second, the interconnections with the universal values of the world; third, the biological constructive function for global sustainability. Mohist had the fame of one of two well-known philosophers of his times, Confucian and Mohist. His ideas had a decisive influence upon the early Chinese thinkers while his visions of meritocracy and the public good helps shape the political philosophies and policy decisions till Qin and Han (202 B.C.-220 C.E.) dynasties. Sun Yet-sen (1902) adopted Mohist concepts “to take the world as one community” (tian xia wei gong) as the rationale of his democratic theory and he highly appraised Mohist concepts of equity and “impartial love” (jian ai). -

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy

Readings In Classical Chinese Philosophy edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe University of Michigan and Bryan W. Van Norden Vassar College Seven Bridges Press 135 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010-7101 Copyright © 2001 by Seven Bridges Press, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Publisher: Ted Bolen Managing Editor: Katharine Miller Composition: Rachel Hegarty Cover design: Stefan Killen Design Printing and Binding: Victor Graphics, Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Readings in classical Chinese philosophy / edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Bryan W. Van Norden. p. cm. ISBN 1-889119-09-1 1. Philosophy, Chinese--To 221 B.C. I. Ivanhoe, P. J. II. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William) B126 .R43 2000 181'.11--dc21 00-010826 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CHAPTER TWO Mozi Introduction Mozi \!, “Master Mo,” (c. 480–390 B.C.E.) founded what came to be known as the Mojia “Mohist School” of philosophy and is the figure around whom the text known as the Mozi was formed. His proper name is Mo Di \]. Mozi is arguably the first true philosopher of China known to us. He developed systematic analyses and criticisms of his opponents’ posi- tions and presented an array of arguments in support of his own philo- sophical views. His interest and faith in argumentation led him and his later followers to study the forms and methods of philosophical debate, and their work contributed significantly to the development of early Chinese philosophy. -

Mozi 31: Explaining Ghosts, Again Roel Sterckx* One Prominent Feature

MOZI 31: EXPLAINING GHOSTS, AGAIN Roel Sterckx* One prominent feature associated with Mozi (Mo Di 墨翟; ca. 479–381 BCE) and Mohism in scholarship of early Chinese thought is his so-called unwavering belief in ghosts and spirits. Mozi is often presented as a Chi- nese theist who stands out in a landscape otherwise dominated by this- worldly Ru 儒 (“classicists” or “Confucians”).1 Mohists are said to operate in a world clad in theological simplicity, one that perpetuates folk reli- gious practices that were alive among the lower classes of Warring States society: they believe in a purely utilitarian spirit world, they advocate the use of simple do-ut-des sacrifices, and they condemn the use of excessive funerary rituals and music associated with Ru elites. As a consequence, it is alleged, unlike the Ru, Mohist religion is purely based on the idea that one should seek to appease the spirit world or invoke its blessings, and not on the moral cultivation of individuals or communities. This sentiment is reflected, for instance, in the following statement by David Nivison: Confucius treasures the rites for their value in cultivating virtue (while virtually ignoring their religious origin). Mozi sees ritual, and the music associated with it, as wasteful, is exasperated with Confucians for valuing them, and seems to have no conception of moral self-cultivation whatever. Further, Mozi’s ethics is a “command ethic,” and he thinks that religion, in the bald sense of making offerings to spirits and doing the things they want, is of first importance: it is the “will” of Heaven and the spirits that we adopt the system he preaches, and they will reward us if we do adopt it. -

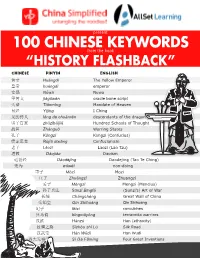

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

View Sample Pages

This Book Is Dedicated to the Memory of John Knoblock 未敗墨子道 雖然歌而非歌哭而非哭樂而非樂 是果類乎 I would not fault the Way of Master Mo. And yet if you sang he condemned singing, if you cried he condemned crying, and if you made music he condemned music. What sort was he after all? —Zhuangzi, “In the World” A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. Although the institute is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. The China Research Monograph series is one of the several publication series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. Send correspondence and manuscripts to Katherine Lawn Chouta, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies 2223 Fulton Street, 6th Floor Berkeley, CA 94720-2318 [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. [Mozi. English. Selections] Mozi : a study and translation of the ethical and political writings / by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel. pages cm. -- (China research monograph ; 68) English and Chinese. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-103-9 (alk. paper) 1. Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. Mozi. I. Knoblock, John, translator, writer of added commentary. II. Riegel, Jeffrey K., 1945- translator, writer of added commentary. III. Title. B128.M79E5 2013 181'.115--dc23 2013001574 Copyright © 2013 by the Regents of the University of California. -

The Environment and Feng Shui Application in Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion, Penang, Malaysia

Eco-Architecture VII 1 THE ENVIRONMENT AND FENG SHUI APPLICATION IN CHEONG FATT TZE MANSION, PENANG, MALAYSIA AZIZI BAHAUDDIN & TEH BOON SOON School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia ABSTRACT Feng Shui, literarily translated as wind and water, forms part of the Chinese traditional architecture theory. The philosophy aims to achieve harmonious equilibrium among nature, buildings and people. It continues to be used in dwelling site selections and layout of buildings as well as in the environmental planning, especially in the Form School Feng Shui school of thought. It focuses on site analysis, landscapes and building placements with emphasis on designing with nature and the environment. This Feng Shui approach can be traced in the building design of the Peranakan style architecture of Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion, a unique architecture in George Town, Penang. It is a mix of Chinese, Malay and colonial building styles. Unfortunately, this mansion has not been verified with the Feng Shui approach in relating the architecture with nature, despite a claim that was made of its application and for other buildings of the same style. This study addresses the cultural sensitivity of this architecture as a case study in embracing nature for its Feng Shui application. Qualitative analysis was employed to determine whether the design of this mansion corresponded well with favourable architectural conditions placed in the environment as stated in the Form School approach. The method applied included measured drawings, ethnography study of the Peranakan culture, interviews with identified Feng Shui masters and the mansion’s owners. The mansion’s architectural design conformed to the philosophy adapted from the Form School approach, especially in the architectural language. -

The Tianxia System and the Search for a Common Ground in the Comparative Ethics of War

The Tianxia System and the Search for a Common Ground in the Comparative Ethics of War Edmund Frettingham and Yih-Jye Hwang This paper explores the conclusions of recent research on the ethics of war in Chinese traditional political thought, asking how they have been shaped by understandings of the nature, meaning and significance of global ethical di- versity. After outlining the major contours of Chinese traditional ethics of war, we propose that the significance of this material has been understood within the terms of both liberal and communitarian meta-ethical assumptions. These assumptions have shaped how the relationship between Chinese and West- ern traditions has been understood, limiting this research in unhelpful ways. While liberal assumptions lead to authors discounting the distinctiveness of Chinese traditions, communitarian approaches seek to find common ground between traditions to mitigate the danger of intercultural conflict. The common ground solution is ultimately undermined by the communitarian assumptions that made it seem urgent. In response to these problems, we propose that a more radically communitarian mode of engagement should guide the compar- ative dimension of research into non-Western ethics of war. Key Words: Comparative ethics of war, Just war, Tianxia, Chinese political thought, Post-Western IR Korean conservatism, Japanese statism, European fascism, progressivism, Parg- *Edmund Frettingham ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University. His research interests include religion and secularism in world politics, ethics, and critical security studies. ** Yih-Jye Hwang ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University. -

The Great Divergence and the Economics of Printing

The Great Divergence and the Economics of Printing Luis Angeles PRELIMINARY. PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE. March 13, 2015 1 Introduction One of the finest paradoxes in global history is the statement by Francis Bacon, champion of empiricism and a major figure in Europe’s intellectual ascendancy, about the importance of inventions in changing human lives. The three great inventions chosen by Bacon to make his case are printing, gunpowder, and the compass. All three were of Chinese origin.1 The failure of China to industrialize ahead of Europe, leading to what Kenneth Pomeranz has termed "The Great Divergence", has puzzled schol- Adam Smith Business School (Economics), University of Glasgow. Gilbert Scott Building, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom. Email: [email protected] . Tel: +44 141 330 8517. I thank, in particular, participants of the 4th Asian Historical Eco- nomics Conference in Istanbul, and seminar participants at the London School of Eco- nomics. I am, of course, liable for all remaining errors. 1 The statement in question is as follows: "Again, we should notice the force, effect, and consequences of inventions, which are nowhere more conspicuous than in those three which were unknown to the ancients; namely, printing, gunpowder, and the compass. For these three have changed the ap- pearance and state of the whole world: first in literature, then in warfare, and lastly in navigation; and innumerable changes have been thence derived, so that no empire, sect, or star, appears to have exercised a greater power and influence on human affairs than these mechanical discoveries." Francis Bacon, Novum Organum (1620), Book I, CXXIX. -

Classics of Tea Sequel to the Tea Sutra Part II GLOBAL EA HUT Contentsissue 104 / September 2020 Tea & Tao Magazine Heavenly天樞 Turn

GLOBAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 September 2020 Classics of Tea Sequel to the Tea Sutra Part II GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 104 / September 2020 Tea & Tao Magazine Heavenly天樞 Turn This month, we return once again to our ongo- ing efforts to translate and annotate the Classics of Tea. This is the second part of the monumental Love is Sequel to the Tea Sutra by Lu Tingcan. This volu- minous work will require three issues to finish. As changing the world oolong was born at that time, we will sip a tradi- tional, charcoal-roasted oolong while we study. bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 49 07 Wind in the Pines The Music & Metaphor of Tea By Steven D. Owyoung 15 Sequel to the Tea Sutra 17 Volume Four 03 Teaware 27 Volume Five Tea Brewing 49 Volume Six 27 Tea Drinking Traditions傳統文章 17 03 Tea of the Month “Heavenly Turn,” Traditional Oolong, Nantou, Taiwan 65 Voices from the Hut “Ascertaining Serenity” By Anesce Dremen (許夢安) 69 TeaWayfarer © 2020 by Global Tea Hut Anesce Dremen, USA All rights reserved. recycled & recyclable No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- 從 tem or transmitted in any form or by 地 any means: electronic, mechanical, 球 天 photocopying, recording, or other- 升 起 wise, without prior written permis- 樞 Soy ink sion from the copyright owner. n September,From the weather is perfect in Taiwan.the grieve well. Theseeditor are a powerful recipe for transformation. We start heading outdoors for some sessions when Suffering then becomes medicine, mistakes become lessons we can. -

Fengshui in Singapore

SUMMONING WIND AND RAIN: STUDYING THE SCIENTIZATION OF FENGSHUI IN SINGAPORE OH BOON LOON NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2010 SUMMONING WIND AND RAIN: STUDYING THE SCIENTIZATION OF FENGSHUI IN SINGAPORE OH BOON LOON (B.Soc.Sci. (Hons.), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2010 Acknowledgements Writing this thesis has been a challenging but rewarding experience, made possible with the grace and kindness of many, and the love and support of the faithful few. It has been a great privilege to re-join NUS and pursue my masters’ programme on a full-time basis after working six years in the civil service. I am grateful to the Ministry of Home Affairs for approving my two years no-pay leave and to Singapore Prison Service for supporting my leave application. The following people deserve much credit for mentoring and assisting me in my academic studies. First, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Professor Michael Hill for his willingness to supervise me, his enthusiasm in sharing his knowledge, and for being gracious and patient with me. I also thank Dr. Daniel Goh for his critical and constructive comments, and sincerely appreciate his help despite his hectic schedule. Similarly, I thank Dr. Misha Petrovic for spending his time to discuss about my research. I am especially grateful to A/P Peter Borschberg, A/P Maribeth Erb, A/P Tong Chee Kiong, and Dr. Narayanan Ganapathy for assisting me in my programme admission and my subsequent upgrade to the NUS Research Scholarship. -

The History of Qing Hao in the Chinese Materia Medica Downloaded From

Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (2006) 100, 505—508 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/trst The history of qing hao in the Chinese materia medica Downloaded from Elisabeth Hsu ∗ Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford, 51 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6PE, UK http://trstmh.oxfordjournals.org/ Received 22 April 2005; received in revised form 2 September 2005; accepted 20 September 2005 KEYWORDS Summary Artemisinin is currently used for treating drug-resistant malaria. It is found in Antimalarial; Artemisia annua and also in A. apiacea and A. lancea. Artemisia annua and A. apiacea were Artemisia annua; known to the Chinese in antiquity and, since they were easily confused with each other,both pro- Artemisinin; vided plant material for the herbal drug qing hao (blue-green hao). This article shows, however, at George Washington University on February 10, 2016 Extraction method; that since at least the eleventh century Chinese scholars recognized the difference between Ethnobotany; the two species, and advocated the use of A. apiacea, rather than A. annua for ‘treating lin- China gering heat in joints and bones’ and ‘exhaustion due to heat/fevers’. The article furthermore provides a literal translation of the method of preparing qing hao for treating intermittent fever episodes, as advocated by the eminent physician Ge Hong in the fourth century CE. His recom- mendation was to soak the fresh plant in cold water, wring it out and ingest the expressed juice in its raw state. Both findings may have important practical implications for current traditional usage of the plant as an antimalarial: rather than using the dried leaves of A.