'The Baggage of William Grant Broughton: the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

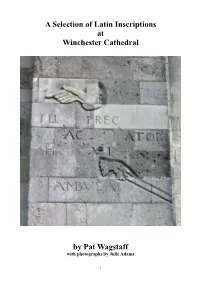

A SELECTION of LATIN INSCRIPTIONS at WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff

A Selection of Latin Inscriptions at Winchester Cathedral by Pat Wagstaff with photographs by Julie Adams 1 A SELECTION OF LATIN INSCRIPTIONS AT WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff Pat Wagstaff was a Cathedral Guide at Winchester between 2002 and 2009. She and her husband moved to Norwich in September 2009, and she is currently a guide at Norwich Cathedral. Introduction The idea for this publication evolved from tours of Latin epitaphs in the Cathedral which I led for Cathedral Guides and for the general public. It is, of necessity only a short selection of epitaphs. I have chosen those which are representative of the people buried or commemorated in the Cathedral and I have also tried to include examples of typical abbreviations and expressions. The translations are my own except for those marked [GC] at the end. Those translations are by Guy Clarke who left for the Guides a file of beautifully handwritten translations. The order of the booklet follows that of a typical guided tour through the Cathedral, beginning at the west end, proceeding along the north side into the Retroquire and then down into the south transept, into the nave and finally into the south nave aisle. The numbers on the Cathedral plan below correspond to the numbers assigned to the epitaphs in the text. Inscriptions marked with an asterisk * are visible only when the chairs have been removed from the nave of the Cathedral. Two of the memorials marked ** are currently under a temporary extension to the nave dais. There are two appendices, one giving notes on common phrases or words used in epitaphs and the other giving information on the way Latin is used to give dates. -

The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, C. 1800-1837

The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, c. 1800-1837 Nicholas Andrew Dixon Pembroke College, Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. November 2018 Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. Nicholas Dixon November 2018 ii Thesis Summary The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, c. 1800-1837 Nicholas Andrew Dixon Pembroke College, Cambridge This thesis examines the various ways in which the Church of England engaged with English politics and society from c. 1800 to 1837. Assessments of the early nineteenth-century Church of England remain coloured by a critique originating in radical anti-clerical polemics of the period and reinforced by the writings of the Tractarians and Élie Halévy. It is often assumed that, in consequence of social and political change, the influence of a complacent and reactionary church was irreparably eroded by 1830. -

Wu Rare Item Post.Pdf (89.03Kb)

Dorothy Wordsworth’s Letter and Its Significance By: Crystal Wu This post shall spotlight Dorothy Wordsworth’s unpublished letter “1820, June 2, Dorothy Wordsworth to Joshua Watson and John James Watson” housed in the Armstrong Browning Library Rare Letters collection. Although Dorothy is not as well-known as her brother William Wordsworth, her letter brings a new insight on the wide connections the Wordsworths have, and how these connections might have possibly influenced William Wordsworth’s change of focus in his later poems. In addition, the letter illustrates the care and thought that Dorothy put into writing the letter. The content of this letter involves Dorothy Wordsworth updating Joshua Watson and John James Watson on the health of Christopher Wordsworth, another brother of Dorothy and William Wordsworth. Interestingly, the letter is divided into parts, with the first part addressed to Joshua, and the second part addressed to John. At the time of the letter, Christopher had been recuperating after a bout of illness. Despite the letter being a personal correspondence, there is an air of formality. This may have been due to Dorothy’s relationship with the Watsons as acquaintances, rather than as close friends. In addition, she discusses the well-being of Mrs. Norris. William and his wife are briefly mentioned at the end of the letter, although simply as a passing remark. At first glance, there seems to be a smaller, cramped handwriting on the first page of the letter, followed by a larger handwriting. Upon further research, it is noted that the handwritings are of two different people, Joshua Watson and Dorothy Wordsworth. -

Introduction

i i i i Introduction WILLIAM GIBSON, OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY GEORDAN HAMMOND, MANCHESTER WESLEY RESEARCH CENTRE AND NAZARENE THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE Peter Benedict Nockles was an undergraduate between 1972 and 1975, then graduate student at Worcester College, Oxford, and subsequently at St Cross College, Oxford, between 1976 and 1982, when he was awarded a DPhil for his research.1 His thesis was supervised by Geoffrey Rowell, chaplain and fellow of Keble College, and later bishop of Gibraltar in Europe. Jeremy Gregory, who in his doctoral studies was researching the Church of England before 1829, writes of this period: Peter’s thesis confirmed that religious history before that date was much more nuanced and far richer than the conventional labels (‘High [and Dry]’, ‘Low Church’, ‘Evangelical’) allowed, and that George Horne, one of the deans of Canterbury I was studying, was an important (but neglected) figure in Anglican theology. As I completed my thesis, Peter was a source of good advice and we both contributed to a number of what turned out to be seminal publications in the 1990s. Peter’s thesis was admired and widely consulted and, urged on by his examiner John Walsh, he produced a significantly revised and extended version of it as a mono- graph. Entitled The Oxford Movement in Context: Anglican High Churchmanship, 1760–1857, it was published by Cambridge University Press in 1994. It was a book that was widely anticipated; numerous books and articles had cited the thesis before it was published. The Oxford Movement in Context is one of those groundbreaking books that it is difficult to imagine being without. -

The Church of England and the Legislative Reforms of 1828-1832: Revolution Or Adjustment?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo The Church of England and the Legislative Reforms of 1828-1832: Revolution or Adjustment? Nicholas Dixon1 Since the 1950s, historians of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Church of England have generally maintained that the Sacramental Test Act (1828), the Roman Catholic Relief Act (1829) and the Reform Act (1832) amounted to a ‘constitutional revolution’, in which Anglican political hegemony was decisively displaced. This theory remains the dominant framework for understanding the effect of legislation on the relationship between church and state in pre-Victorian England. This article probes the validity of the theory. It is argued that the legislative reforms of 1828-32 did not drastically alter the religious composition of Parliament, which was already multi- denominational, and that they incorporated clauses which preserved the political dominance of the Church of England. Additionally, it is suggested that Anglican apprehensions concerning the reforming measures of 1828-32 resulted from an unfounded belief that these reforms would ultimately result in changes to the Church of England’s formularies or disestablishment, rather than from the actual laws enacted. Accordingly, the post-1832 British parliamentary system did not in the short term militate against Anglican interests. In light of this reappraisal, the legislative reforms of 1828-32 may be better understood as an exercise in ‘constitutional adjustment’ as opposed to a ‘constitutional revolution’. Following the Reform Act and the ensuing general election of 1832, the Duke of Wellington wrote to the Conservative author John Wilson Croker: 1 The research upon which this article is based was funded by an Arts and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership studentship, grant no. -

William Stevens (1732-1807): Lay Activism in Late Eighteenth-Century Anglican High Churchmanship

i William Stevens (1732-1807): Lay Activism in late Eighteenth-Century Anglican High Churchmanship Robert M Andrews BA (Hons) Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Church History Murdoch University 2012 ii I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………… Robert M Andrews iii Abstract Set within the context of a neglected history of lay involvement in High Churchmanship, this thesis argues that William Stevens (1732-1807)—a High Church layman with a successful commercial career—brought to the Church of England not only his piety and theological learning, but his wealth and business acumen. Combined with extensive social links to some of that Church’s most distinguished High Church figures, Stevens exhibited throughout his life an influential example of High Church ‘lay activism’ that was central to the achievements and effectiveness of High Churchmanship during the latter half of the eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth. In this thesis, Stevens’s lay activism is divided into two sub-themes: ‘theological activism’ and ‘ecclesiastical activism’. Theological activism was represented primarily by Stevens’s role as a theologian or ‘lay divine’, a characteristic that resulted in numerous publications that engaged in contemporary intellectual debate. Ecclesiastical activism, on the other hand, represented Stevens’s more practical contributions to Church and society, especially his role as a philanthropist and office holder in a number of Church of England societies. Together, Stevens’s intellectual and practical achievements provide further justification of the revisionist claim that eighteenth-century Anglican High Churchmanship was an active ecclesiastical tradition. -

College of S. Augustine Canterbury: Participants At

COLLEGE OF S. AUGUSTINE CANTERBURY PARTICIPANTS AT THE CONSECRATION, S. PETER’S DAY 1848 Key BLUE name, a person in a nominated seat in the chapel RED name a person not in a nominated seat but present in the chapel (The Times; The Illustrated London News) BLACK name possibly present in the chapel [BLUE name] name as given in the chapel seating plan; the personal name may be different ; (eg [Earl Nelson] is Horatio NELSON) (1851 census) census information from the returns closest to 1848 PROBATED WILLS indicate participants’ wealth; this URL interprets the value of their deceased estates. http://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/ Introductory note The newly built Missionary College of S Augustine was consecrated on 29 June 1848. The funds to purchase and to build (and then to pay its first principal William Hart Coleridge and his assistant tutors) had been raised by a group of enthusiasts with shared intentions. First, to have a central training college for the Church of England, where young men (aged 18 plus) would be trained in oriental languages and culture as well as Christian faith and practice before they were sent out as missionaries to India, Asia, Africa, the Pacific, and the Americas. Secondly, to have a showcase for their own vision of the Anglican church: a branch of the Catholic church, bearing witness to a long history stretching back to those first missionaries who came from Rome with their leader S Augustine to Kent in 597 AD. They were making a statement about the continuity of the Anglican church. It was founded 1,250 years ago, it was reformed but not broken at the Protestant Reformation, and now they were proud to be standing again on the spot where Augustine and his monks had begun their missionary work in ancient England. -

William Stevens (1732-1807): Lay Activism in Late Eighteenth-Century Anglican High Churchmanship

i William Stevens (1732-1807): Lay Activism in late Eighteenth-Century Anglican High Churchmanship Robert M Andrews BA (Hons) Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Church History Murdoch University 2012 ii I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………… Robert M Andrews iii Abstract Set within the context of a neglected history of lay involvement in High Churchmanship, this thesis argues that William Stevens (1732-1807)—a High Church layman with a successful commercial career—brought to the Church of England not only his piety and theological learning, but his wealth and business acumen. Combined with extensive social links to some of that Church’s most distinguished High Church figures, Stevens exhibited throughout his life an influential example of High Church ‘lay activism’ that was central to the achievements and effectiveness of High Churchmanship during the latter half of the eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth. In this thesis, Stevens’s lay activism is divided into two sub-themes: ‘theological activism’ and ‘ecclesiastical activism’. Theological activism was represented primarily by Stevens’s role as a theologian or ‘lay divine’, a characteristic that resulted in numerous publications that engaged in contemporary intellectual debate. Ecclesiastical activism, on the other hand, represented Stevens’s more practical contributions to Church and society, especially his role as a philanthropist and office holder in a number of Church of England societies. Together, Stevens’s intellectual and practical achievements provide further justification of the revisionist claim that eighteenth-century Anglican High Churchmanship was an active ecclesiastical tradition. -

Augustus Short: the Early Years of a Modern Educator 1802-1847

Michael Whiting Michael Whiting is an Anglican priest and an Archdeacon Emeritus in the Diocese of Adelaide. Prior to retiring in 2012, he was chaplain to the archbishop of Adelaide and archdeacon for education and formation. For over thirty years he led Roman Catholic and Anglican schools, his final appointment being as deputy headmaster and chaplain of St Peter's College, Adelaide. Since 2014, Michael has been a Visiting Research Fellow in History at the University of Adelaide. The study of Bishop Augustus Short has been a special interest for many years. This volume was preceded by Augustus Short and the Founding of the University of Adelaide, commissioned and published by the University of Adelaide Press in 2014. AUGUSTUS SHORT The early years of a modern educator 1802-1847 by Michael Whiting with a Foreword by The Very Reverend Professor Martyn Percy Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The Barr Smith Press is an imprint of the University of Adelaide Press, under which titles about the history of the University are published. The University of Adelaide Press publishes peer reviewed scholarly books. It aims to maximise access to the best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2018 Michael Whiting This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. -

The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811-2011

Distinctive and Inclusive The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811–2011 Lois Louden Distinctive and Inclusive The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811–2011 The National Society Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ Published 2012 by the National Society Copyright © The National Society 2012 Front Cover image: © Dean & Chapter of Westminster/Picture Partnership All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any for, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system without written permission which should be sought from the Copyright and Contracts Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3AZ. E-mail: [email protected] Lois Louden asserts her right under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as Author of this Work. Cover design and typesetting by [email protected] Printed by Print Guy Distinctive and Inclusive The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811–2011 Lois Louden Contents Author’s note Introduction .............................................................................................. Page 1 Chapter 1 The origins and context of the National Society ................... Page 8 Chapter 2 Objectives and organisation 1811–1840................................. Page 15 Chapter 3 Expanding challenges 1840–1870 ........................................... Page 27 Chapter