Without Nuremberg—What?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials

Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Memorium Nürnberger Prozesse Hirschelgasse 9-11 90403 Nürnberg Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-66 89 Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-54 20 Telefax: 0911 / 2 31-1 42 10 E-Mail: [email protected] www.museen.nuernberg.de – Press Release From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials Nuremberg’s name is linked with the NSDAP Party Rallies held here between 1933 and 1938 and – Presseinformation with the „Racial Laws“ adopted in 1935. It is also linked with the trials where leading representatives of the Nazi regime had to answer for their crimes in an international court of justice. Between 20 November, 1945, and 1 October, 1946, the International Military Tribunal’s trial of the main war criminals (IMT) was held in Court Room 600 at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice. Between 1946 and 1949, twelve follow-up trials were also held here. Those tried included high- ranking representatives of the military, administration, medical profession, legal system, industry Press Release and politics. History Two years after Germany had unleashed World War II on 1 September, 1939, leading politicians and military staff of the anti-Hitler coalition started to consider bringing to account those Germans responsible for war crimes which had come to light at that point. The Moscow Declaration of 1943 and the Conference of Yalta of February 1945 confirmed this attitude. Nevertheless, the ideas – Presseinformation concerning the type of proceeding to use in the trial were extremely divergent. After difficult negotiations, on 8 August, 1945, the four Allied powers (USA, Britain, France and the Soviet Union) concluded the London Agreement, on a "Charter for The International Military Tribunal", providing for indictment for the following crimes in a trial based on the rule of law: 1. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

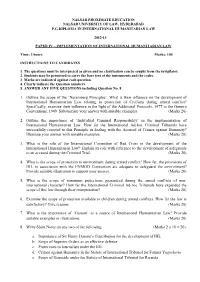

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

Bibliography Primary Sources Biddle, Francis. "The

Bibliography Primary Sources Biddle, Francis. "The Nürnberg Trial." In Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, 200-12. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Francis Biddle, the primary American judge of the IMT, wrote this short piece only months after the conclusion of the trials. His purpose was largely to clarify common misconceptions about the trial - primarily their "root in victor's justice." This article helped clarify some essential points of the trial and its justification for me. Dodd, Christopher J., and Lary Bloom. Letters from Nuremberg: My Father's Narrative of a Quest for Justice. New York: Crown Pub., 2007. Print. This is a collection of letters written by Thomas Dodd to his family members back home detailing the events of the International Military Tribunal and his involvement in it. These provide a unique first-hand look at what the prosecution team was doing in Nuremberg and helped provide a better understanding of the prosecutors' strategy and mentality throughout the trial. European Advisory Council. Charter of the International Military Tribunal - Annex to the Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the uropean Axis ("London Agreement"). August 8, 1945. The Charter of the IMT, commonly known as the "London Charter," authorized the formation of the International Military Tribunal and outlined the rules and procedures it was to follow. This is one of the central documents of the trial, and its contents were drawn upon in future trials and in the Rome Statute. It was incredibly important to this project, and it is featured in full on the website. -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

JUDGEMENT at NUREMBERG 1946 Fact Sheet

JUDGEMENT AT NUREMBERG 1946 Fact Sheet On the morning of October 16, 1946, five of the Nazi war criminals who had been tried and convicted at the Nuremburg Trials were seated at the prison morning mess table. Their breakfast was interrupted by a United States Soldier who asked for their autographs. They had never seen this person before and his unfamiliar face aroused the suspicions of Herman Goering. When he inquired as to the identity of the mysterious soldier he learned that Master Sergeant John Woods was the official hangman for the prisoners and that his real purpose had not been collecting autographs but estimating bodyweight of three of the five men seated at the table. The gallows had been secretly constructed in the prison gym and the executions would begin that evening. Goering was first on the list. He had stated earlier that if he was to be executed, it should be by firing squad instead of being hung like a common criminal. Early that evening Goering asked the guard to go into the luggage room and bring him some of his personal belongings. Within an hour, he had committed suicide by biting down on a glass capsule filled with cyanide that he had secretly hidden in his belongings. Sergeant Woods, on hearing of Goering’s death, was enraged at missing the opportunity of hanging the infamous war criminal, but continued with the other hangings as scheduled. Woods was a professional who had hanged hundreds of people and these executions were no different. The routine for hanging each convicted criminal was the same. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

High Command Case: a Study in Staff and Command Responsibility

JOHN JAY DOUGLASS* Colonel, JAGC High Command Case: A Study in Staff and Command Responsibility Less than twenty-five years after the conclusion of the major World War I1war crimes trials, international jurists, historians and the general public are not clear as to, nor are they apparently concerned with, the authority, procedure or even the significant legal decisions of the war crimes trials held both in Europe and the Far East following World War 11.1 Even a mere twenty-five years of experience indicates there will be other trials of those accused of criminal acts in war. Such trials, as well as international lawmakers, should well review the German High Command Trial before the United States Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1948. The lessons of this trial may well be the most important of those from any of the trials held following World War 11. The thrust of this trial and its results relate to the authority of command- ers of military forces for actions of their troops and their personal respon- sibility, as well as the responsibility of staff officers in senior staff positions, for'actions taken by them or carried on under their direction. As a result of recent developments within the United States, arising from the war in Vietnam, it is worthwhile to review the German High Command Trial and to analyze its relationship to the present state of the law. The legal question of criminal responsibility of military commanders and staff officers who do *Commandant (Dean), The Judge Advocate General's School, U.S. -

Anti-Jewish Laws Timeline

Materials ANTI-JEWISH LAWS TIMELINE This Jewish storefront was vandalised during Kristallnacht in Magdeburg, Germany, November 9-10, 1938. (Montreal Holocaust Museum Collection) 1933 1935 1938 1939 1940 1941-1942 January 30, 1933 1935 April 26, 1938 November 9-10, 1938 September 1, 1939 May 20, 1940 June 1941 to January 1942 Adolf Hitler is appointed The Law for the Protection of Nazis force Jews to register Kristallnacht: A wave of Invasion of Poland: Germany The Auschwitz concentration camp Following the German invasion of the Chancellor of Germany. German Blood and Honour their assets, a first step toward state-organised attacks attacks Poland and World War II opens in occupied Poland. It will Soviet Union, four Einsatzgruppen and the German Citizenship total exclusion from the target Jewish businesses, begins. By the end of the month, eventually become a mixed camp (mobile killing units) massacre 1 February 28, 1933 Law are passed. Known German economy. synagogues, apartments Poland is divided between (concentration and death camp) million Jews. Using the Reichstag (German as the “Nuremberg Laws”, across Germany and Austria. Germany and the USSR. Jews where nearly 1 million Jews are parliament) fire as pretext, Hitler they prohibit marriage and July 25, 1938 Jews are forced to pay fines on the German side are almost murdered. issues emergency decrees sexual relationships between Jewish doctors are forbidden of over one billion German immediately subjected to anti- that mark the end of all basic Germans and Jews and state to treat ‘Aryan’ patients marks. Jewish measures. freedoms, including freedom of that only persons of “German speech, press, assembly and or related blood” can be August 17, 1938 November 15, 1938 October 28, 1939 citizens.