Master of Arts Thesis the Problem of Understanding in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress The last two hundred years of Hindu–Christian encounters have produced distinctive forms of Hindu thought which, while often rooted in the broad philosophical-cultural continuities of Vedic outlooks, grappled with, on the one hand, the colonial pressures of European modernity, and, on the other hand, the numerous critiques by Christian theologians and missionaries on the Hindu life-worlds. Thus, the spectrum of Hindu responses from Raja Rammohun Roy through Swami Vivekananda to S. Radhakrishnan demonstrates attempts to creatively engage with Christian representations of Hindu belief and practice, by accepting their prima facie validity at one level while negating their adequacy at another. For instance, these figures of neo-Hinduism accepted that such ‘corruptions’ as Hinduism’s alleged idol- worship, anti-worldly ethic, caste-based distinctions and the like were all too visible on the socio-cultural domain, while they formulated revamped Vedic or Vedantic visions within which these were to be either rejected as excrescences or given demythologised interpretations. In Swami Vivekananda, we find on some occasions a more strident rejection of certain aspects of western civilization as steeped in materialist ‘excesses’ which needed to be purged through the light of Vedantic wisdom. Through such hermeneutical processes of retrieval, often carried out within contexts structured by British colonialism, these figures were able to offer forms of Hinduism that were signifiers not of the Oriental depravity that the British administrators, scholars and missionaries had claimed to perceive on the Indian landscapes but of a spiritual depth that transcended national, cultural and ethnic boundaries. -

MA Philo. Credt Semester I-II

Syllabus M.A. (Philosophy) (Semester and Credit system) (Semesters I and II Operative from 2008-9) (Modified from year 2010-2011) Department of Philosophy Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Bhavan University of pune, Pune-411007 Tel. 020-25601314/15 E-mail: [email protected] General Instructions 1) In Semesters I and II the first two courses (viz., PH 101, PH 102, PH 201, PH 202) are compulsory. 2) Out of the list of Optional courses in the Semester I and II and out of the Group A and Group B in the Semester III and IV two courses each are to be offered. 3) A student has to successfully complete 16 courses for the Master’s Degree. 4) A student can choose all the 16 course in the Department of Philosophy OR A student desirous to do M.A. in Philosophy has to choose at least 12 courses(of 4 credits each) from the Department of Philosophy (i. e., at least three courses -including compulsory courses, if any,- each semester) and 4 courses (i. e., at the most 16 credits in all, one course of 4 credits per semester) from any other department/s as interdisciplinary courses, such that the total number of credits is at least 64 out of which 75% credits are from philosophy department. 5) Dissertation and Open Course: In addition to a wide range of options, the syllabus provides for (i) Dissertation and (ii) Open Course in semesters III and IV the details of which will be declared separately. 6) The lists of readings and references will be updated by the Department and by the respective teachers from time to time. -

Unit 1 NYĀYA PHILOSOPHY

Unit 1 NYĀYA PHILOSOPHY Contents 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Epistemology 1.3 Theory of Causation (Asatkāryavāda) 1.4 Self and Liberation 1.5 The Concept of God 1.6 Let Us Sum Up 1.7 Key Words 1.8 Further Readings and References 1.9 Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit, you will learn the Nyāyika’s doctrine of valid sources of knowledge and their arguments on self and liberation. Further, you will also learn the Nayāyika’s views on God. After working through this unit, you should be able to: • explain different kinds of perception • discuss nature and characteristics of inference • elucidate Nyāya concept of self • illustrate Nyāyika’s views on liberation • examine Nyāyika’s arguments on testimony as a valid source of knowledge 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Nyāya School is founded by the sage Gotama, who is not confused as Gautama Buddha. He is familiarized as ‘Aksapāda’. Nyāya means correct thinking with proper arguments and valid reasoning. Thus, Nyāya philosophy is known as tarkashāstra (the science of reasoning); pramānashāstra (the science of logic and epistemology); hetuvidyā (the science of causes); vādavidyā (the science of debate); and anviksiki (the science of critical study). The Nyāya philosophy as a practitioner and believer of realism seeks for acquiring knowledge of reality. 1.2 EPISTEMOLOGY The Nyāya school of thought is adhered to atomistic pluralism and logical realism. It is atomistic pluralism on the account that atom is the constituent of matter and there are not one but many entities, both material and spiritual, as ultimate constituents of the universe. -

B.A. Honours in Sanskrit Choice Based Credit System Semester

B.A. Honours in Sanskrit Choice Based Credit System Semester Pattern Semester Core Course Ability Enhancement Skill Enhancement Elective Discipline Specific (DSC) Elective Generic (CC) Compulsory Course Course (GE) (AECC) I English-1 Environmental Studies GE - 1 -Darshana DSC-1A –Vyakarana DSC-2A –Hindi DSC-3A –Marathi II English-2 Sociology & MIL GE – 2 -Darshana DSC-1B –Vyakarana DSC-2B–Hindi DSC-3B –Marathi III English-3 SEC 1 – Acting & GE – 3 -Darshana DSC-1C –Vyakarana Script Writing DSC-2C –Hindi DSC-3C -Marathi IV English-4 SEC 2 - Music GE – 4 -Darshana DSC-1D –Vyakarana DSC-2D –Hindi DSC-3D -Marathi V** DSC-5- Vyakarana DSE – 1- Veda DSC-6– Sahitya DSE – 2-Puran DSC 7- Darshan shastra DSE –3-Science in Sanskrit (Theory) VI** DSC-8-Vyakarana DSE – 4 Veda DSC-9 – Sahitya DSE –5 Puran DSC 10- Darshan shastra DSE –6 Science in Sanskrit (Project Work) B.A. Honours Sanskrit Choice Based Credit System Semester Paper Subjects Credits Total Marks I 1 English-1 6 X 1 6 100 2 DSC-1A –Vyakarana 4 X 1 4 100 3 DSC-2A –hindi 4 X 1 4 100 4 DSC-3A Marathi 4 X 1 4 100 5 Environmental Studies 4x 1 4 100 6 GE - 1 - Darshana 4 X 1 4 100 Total 26 II 1 English-2 6 X 1 6 100 2 DSC-1B –Vyakarana 4 X 1 4 100 3 DSC-2B -hindi 4 X 1 4 100 4 DSC-2B Marathi 4 x 1 4 100 5 MIL 4 X 1 4 100 6 GE - 2 - Darshana 4 X 1 4 100 Total 26 III 1 English3 4 X 1 4 100 2 DSC -1C –Vyakarana 4 X 1 4 100 3 DSC 2C Hindi 4 X 1 4 100 4 DSC 3C Marathi 4 X 1 4 100 5 GE – 3 - Darshana 4 x 1 4 100 6 SEC1 – Acting & Script Writing 4 X 1 4 100 Total 24 IV 1 English 4 4 X 1 4 100 2 DSC-1D -

A Survey of Indian Logic from the Point of View of Computer Science

Sadhana, "Col. 19, Part 6, December 1994, pp 971-983. © Printed in India A survey of Indian logic from the point of view of computer science V V S SARMA Department of Computer Science & Automation, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, India Abstract. Indian logic has a long history. It somewhat covers the domains of two of the six schools (darsanas) of Indian philosophy, namely, Nyaya and Vaisesika. The generally accepted definition of In- dian logic over the ages is the science which ascertains valid knowledge either by means of six senses or by means of the five members of the syllogism. In other words, perception and inference constitute the sub- ject matter of logic. The science of logic evolved in India through three ~ges: the ancient, the medieval and the modern, spanning almost thirty centuries. Advances in Computer Science, in particular, in Artificial Intelligence have got researchers in these areas interested in the basic problems of language, logic and cognition in the past three decades. In the 1980s, Artificial Intelligence has evolved into knowledge-based and intelligent system design, and the knowledge base and inference engine have become standard subsystems of an intelligent System. One of the important issues in the design of such systems is knowledge acquisition from humans who are experts in a branch of learning (such as medicine or law) and transferring that knowledge to a computing system. The second important issue in such systems is the validation of the knowl- edge base of the system i.e. ensuring that the knowledge is complete and consistent. -

Christianities of South Asia

SMC456H1F: INDIAN CHRISTIANITY RLG3280H: CHRISTIANITIES OF SOUTH ASIA MEETING TIMES: Tuesdays, 6-9 pm, in Teefy Hall 103 Instructor: Reid B. Locklin Office: Odette Hall 130 Phone: 416.926.1300, x3317 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: T 10:10-12 noon and by chance or appointment Email Policy: I will attempt to respond to legitimate email enquiries from students within 3-4 days. If you do not receive a reply within this period, please re-submit your question(s) and/or leave a message by telephone. Where a question cannot be easily or briefly answered by email, I will indicate that the student should see me during my posted office hours. Course Description This seminar explores the claim of diverse Christian traditions in South Asia to be religious traditions of South Asia, with special attention to these traditions’ indigenisation and social interactions with majority Hindu traditions. Our study will begin with an overview of the historical development of Christianity in India from the first century CE to the present. In a second unit, we move to close readings of three major theological articulations for and against an indigenous South Asian Christianity: M.M. Thomas, Ram Swarup and Sathianathan Clarke. Finally, our attention will turn to the concept of “ritual dialogue” in Christian practice and the ethnographic study of Christian communities in India. Most of our attention will be focused on Christian traditions in South India, but students are encouraged to choose topics related to Christianity in other parts of India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and/or Bhutan for their research papers. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Dayanand Anglo-Vedic School of Lahore: a Study of Educational Reform in Colonial Punjab, Ca

The Dayanand Anglo-Vedic School of Lahore: A Study of Educational Reform in Colonial Punjab, ca. 1885-1925. Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von: Ankur Kakkar Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Gita Dharampal-Frick Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rahul Mukherji Heidelberg, April 2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF MAPS AND TABLES ................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 11 CHAPTER 1: EDUCATION POLICY IN COLONIAL INDIA. A HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, CA. 1800-1880 ........................................................................................................................ 33 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 33 ‘INDIGENOUS’ INDIAN EDUCATION : A COLONIAL SURVEY, CA. 1820-1830 ......................................... 34 Madras ........................................................................................................................... 38 Bombay .......................................................................................................................... 42 Bengal ........................................................................................................................... -

New Arrivals – Central Library – Feb-Mar 2019 Vol

New Arrivals – Central Library – Feb-Mar 2019 Vol. 19, Issue : 2-3 Home Thesis Articles Aerospace Engineering Journalism & Communication Biological / Geological Sciences Language, Linguistics, Literature Chemical/Chemistry Management Civil Engineering Mathematics Computer Science Mechanical Engineering Electrical Engineering Medical Science Electronics & Communication Physics Environmental Engineering Social Sciences Energy Engineering Spiritual Science Generalia Transport Vehicle Engineering Children’s Collections Astrology/Astrophysics/Astronomy Rendering format Title : subtitle / Author’s name : Publisher’s name, Year of Publication Call No. Chemical / Chemistry Computational chemistry and molecular modeling / Ramachandran, K I. : Springer, 2008 54-122:004.94 P80 [67204] Click here for more details Vol.19, Issue: 2-3 ASE-Central Library Coimbatore Chemistry for engineers - Vol. 1 / Ramachandran, T. : Vijay Nicole, 2004 54:62 P51.1 [67206] Click here for more details Top Computer Science Introduction to microcontrollers and their applications / Padmanabhan, T R.: Narosa Publishing, 2007 004.318MIC P73 [67199] Click here for more details Introduction to computer science using python : a computational problem - solving focus / Dierbach, Charles. 004.438PYT Q31 [67094] Click here for more details Insight into data mining : theory and practice / Soman, K P. : PHI Learning, 2006 004.658:025.4.036 P64 [67192] Click here for more details Vol.19, Issue: 2-3 ASE-Central Library Coimbatore Cyber security cyber crime and cyber forensics / Raghu Santanam.: Information Science Reference, 2011 004.7.056 Q15 [67202] Click here for more details Cryptography and security / Shyamala, C K. : Wiley India, 2011 004.7.056.55 Q00;10 [67197] Click here for more details Mathematical principles of the internet - vol. 1 : engineering fundamentals / Bhatnagar, Nirdosh. -

Philosophy, Eighth Edition

P.G. 2nd Semester Paper: PHL801C (Core) Western Epistemology (1850-1964) Credits: 4 = 3+1+0 (48 Lectures) 1. Rationalism-empiricism debate Cartesian method of Doubt and modern epistemological foundationalism; Spinoza’s threefold division of knowledge; Leibnitz on knowledge, Rationalist notion of innate ideas and Locke’s critique of it; Locke’s account of knowledge acquisition, Berkeley’s idealistic empiricism; Hume’s sceptical empiricism; Relations of ideas and matters of fact. 2. Kant’s critical idealism: Kant’s Copernican revolution; Notion of the transcendental; structure of sensibility and understanding; Division of judgements and possibility of synthetic a Priori judgements; Transcendental idealism. 3. Knowledge as justified true belief 4. The Gettier problem; Responses to it Reading List: 1. Cahn, Steven M., ed. 2012. Classics of Western Philosophy, Eighth Edition. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing 2. Pojman, Louis P. 2003. Theory of Knowledge: Classic and Contemporary Readings, Third Edition. Andover, UK: Cengage Learning. 3. Rescher, Nicholas. 2003. Epistemology: An Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge, Series: SUNY Series in Philosophy. Albany, NY: State University of New York 4. Crumley II, Jack S. 2009. An Introduction to Epistemology, Second Edition, Series: Broadview Guides to Philosophy. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press. 5. Copleston, Frederick. 1993. A History of Philosophy, 11 Volumes. New York: Image. (relevant portions). 6. Zalta, Edward N. ed. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, URL: http://plato.stanford.edu/(relevant articles) Paper: PHL802C (Core) Indian Epistemology and Logic Credits: 4 = 3+1+0 (48 Lectures) 1. The Indian method of Purvapaksa and Siddh푎nta; Anviksiki and Anumiti 2. Theories of error (Khyativada): Yogacara Buddhist’s atmakhyativada; Prabhakara mimamsaka’s akhyativada; Naiyayika’s anyathakhyativada; Advaitin’s anirvacaniya- khyativada; Bhatta mimamsaka’s viparitakhyativada; Samkhya’s sadasad-Khyativada; Visistadvaitin’s Satkhyativada 3. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

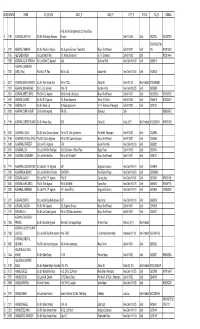

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P.