Jewish Women's Experiences During Their Internment in Auschwitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNEY to AUSCHWITZ 2018 June 23 - July 1 Walk in the Steps of Eva Kor, Holocaust Survivor and Forgiveness Advocate

JOURNEY TO AUSCHWITZ 2018 June 23 - July 1 Walk in the steps of Eva Kor, Holocaust survivor and forgiveness advocate Join CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center for an extraordinary experience as we travel to Auschwitz with survivor Eva Mozes Kor. As we walk in her footsteps, you will hear Eva’s firsthand account of her arrival at Auschwitz, separation from her family, experimentation by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, the struggle for survival, and her and her twin sister Miriam’s liberation by the Soviet Army on January 27, 1945. “Complete” Trip Package: $3900 Preliminary Itinerary includes: • Economy-class flight from Chicago • Staying in beautiful and historic Krakow O’Hare airport • Visit to the Wieliczka Salt Mine • Hotel accommodations • Tour of Krakow’s Old Town, including Wawel • Land transportation Castle, St. Mary’s Church, and Market Square • Daily breakfast • Tour of the Jewish Quarter and Plaszow • Three lunches Memorial • Five evening meals • Tour of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz-Birkenau • Free day to explore on your own “Land” Trip Package: $2600 • Hotel accommodations Please complete all registration materials • Land transportation and return them to CANDLES with a • Daily breakfast • Three lunches $750 nonrefundable deposit to secure • Five evening meals your spot. Registration will remain open *With this option you arrange and purchase until March 14, 2018 or until capacity is your own travel to and from Poland full. Register online at www.candlesholocaustmuseum.org/trips or mail in registration forms to CANDLES Holocaust Museum. CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center 1532 South Third Street Terre Haute, IN 47802 +1.812.234.7881 [email protected] About CANDLES and Eva Kor By providing trip participants with an immersive experience in the historical setting of Auschwitz, we hope to foster powerful breakthroughs in awareness of our respective roles in creating a world based on hope, healing, respect, and responsibility. -

Project Deliverable Holocaust Background Text How Is It Possible That a Man with Such Hateful, Devastating Intentions Can Gain A

Project Deliverable Holocaust Background Text How is it possible that a man with such hateful, devastating intentions can gain as much power as Adolf Hitler did before and during World War II? It is a common belief that in order for people to follow a hateful leader, they must themselves be hateful people. However, it has been shown that that it not necessarily true and this is how Hitler was able to gain his power. In further research, it is understood that people did not necessarily agree with his anti-Semitism beliefs but rather agreed with his other beliefs and ignored his extreme anti-Semitism. [1] Despite losing a Presidential election in 1932, through this process, Hitler began to make a name for himself and gained political attention. However, it wasn't until he was appointed chancellor months later that he was able to start his rise to power. Even though Hitler freely expressed his strong distaste toward the Jews, it was his "powerful leadership, the promise of a reborn Germany, the interests of the common people, and above all, strong anti-Marxism" that made his leadership attractive to the German population. [1] In 1933, when Hitler was elected, there were only half a million Jews in all of Germany. This means that they accounted for less than one percent of the German population. Despite such a low population, the Jews heightened their visibility by high concentrations in certain cities and overrepresentation in certain businesses. "German Jews enjoyed freedom of religion and legal equality, including the right to vote. In contrast, Jews in Russia and Eastern Europe were still fleeing pogroms. -

Liberation & Revenge

Episode Guide: Orders & Initiatives September 1941–March 1942 Jews from the Lódz ghetto board deportation trains for the Chelmno death camp. Overview "Orders and Initiatives" (Disc 1, Title 2, 48:27) highlights the crucial decision-making period of the Holocaust and reveals the secret plans of Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Reinhard Heydrich to annihilate the Jews. At a conference in January 1942, the Nazis plan how to achieve their goals. The first gas chambers are built at Auschwitz and the use of Zyklon B is developed. German doctors arrive to oversee each transport, deciding who should live and who should die. In the program's Follow-up Discussion (Disc 2, Bonus Features, Title 8, 7:18), Linda Ellerbee interviews Claudia Koonz, professor of history at Duke University and author of The Nazi Conscience (Belknap, 2003), and Edward Kissi, professor of Africana studies at the University of South Florida and an expert on international relations and human rights. Target Audience: Grades 9-12 social studies, history, and English courses Student Learning Goals • Citing specific events and decisions, analyze how the Nazi mission changed from September 1941 to March 1942, explaining the reasons for the changes. • Compare Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II (Birkenau) in terms of location, purpose, population, and living conditions. • Identify the incremental steps the Nazis used to isolate Jews and deport them from their home environments to death camps, and the effects on Jews, their neighbors, and the Nazis at each stage. • Summarize how and why many European nations collaborated with the Nazis, including their history of antisemitism. -

Thesis Title the Lagermuseum Creative Manuscript and 'Encountering Auschwitz: Touring the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum' C

Thesis Title The Lagermuseum Creative Manuscript and ‘Encountering Auschwitz: Touring the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum’ Critical Thesis Author Dr Claire Griffiths, BA (Hons), MA, PhD Qualification Creative and Critical Writing PhD Institution University of East Anglia, Norwich School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing Date January 2015 Word Count 91,102 (excluding appendices) This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract The Lagermuseum My creative manuscript – an extract of a longer novel – seeks to illuminate a little- known aspect of the history of the Auschwitz concentration and death camp complex, namely the trade and display of prisoner artworks. However, it is also concerned with exposing the governing paradigms inherent to contemporary encounters with the Holocaust, calling attention to the curatorial processes present in all interrogations of this most contentious historical subject. Questions relating to ownership, display and representational hierarchies permeate the text, characterised by a shape-shifting curator figure and artworks which refuse to adhere to the canon he creates for them. The Lagermuseum is thus in constant dialogue with my critical thesis, examining the fictional devices which often remain unacknowledged within established -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

An Interview with Eva Mozes-Kor

\\server05\productn\G\GHS\8-1\GHS106.txt unknown Seq: 1 22-SEP-10 9:33 INTERVIEW Forgiveness: The Key to Self-Healing— An Interview with Eva Mozes-Kor Joanie Eppinga Eva Mozes-Kor was ten years old when she and her family were deported from their home in Transylvania to Auschwitz. There, Dr. Josef Mengele was doing medical experiments on twins. Eva’s mother, father, and two older sisters were put to death in the gas chambers, but Eva and her twin sister Miriam were preserved to be subjected to experiments. Eva was given an injection that nearly killed her at the time, and Miriam died of the aftereffects of the experiments many years later. As an adult, having married and moved to America, Eva watched her sister struggle with lingering medical issues. She donated a kidney to Miriam and tried to gather information about what had been done to her sister at Auschwitz, but Mengele’s files have never been recovered. Eva’s search to find more information, or even Mengele himself, was unsuccessful; but in the course of her quest, Eva discovered the powerful healing effects of for- giveness. On May 20, 2010, she met with our editor, Joanie Eppinga, at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Terre Haute, Indiana that she started fifteen years ago, and gave the following interview. EPPINGA: What would you have liked to have seen happen if Mengele had been caught? MOZES-KOR: My point was not that he needs to be caught. My point is that if he is alive, or was alive, he should have been found so that the survivors would have the information that has been taken away with him. -

Review of 2016 Programs

Olga Lengyel, 1908 - 2001 Review of 2016 Programs ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 | Table of Contents I. About The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights and The Memorial Library 2 II. The 2016 Summer Seminar on Holocaust Education 3 III. Mini-grant Program 6 IV. TOLI Satellite Seminar Program 14 V. Leadership Institute in New York City 26 VI. Professional Development/Conferences 27 VII. Seminar in Austria 28 VIII. Summer Seminar in Romania 34 IX. Summer Seminar in Bulgaria 38 X. Appendices 42 Appendix A: List of Participating Schools, Summer Seminar 2016 Appendix B: Calendar of Activities, Summer Seminar 2016 Appendix C: List of Participating Schools, Leadership Institute 2016 Appendix D: Calendar of Activities, Leadership Institute 2016 Faculty and Staff of the Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights: Sondra Perl, PhD, Program Director Jennifer Lemberg, PhD, Associate Program Director Wendy Warren, EdD, Satellite Seminar Coordinator Micha Franke, Dipl.Päd., Teaching Staff, New York and International Programs Oana Nestian Sandu, PhD, International Programs Coordinator Alice Braziller, MA, Teaching Staff, New York 2 | I. About the Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights (TOLI) and the Memorial Library The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights (TOLI) is a New York-based 501(c)(3) charitable organization providing professional development to inspire and sustain educators teaching about the Holocaust, genocide, and human rights in the United States and overseas. TOLI was created to further the mission of the Memorial Library, a private nonprofit established in 1962 by Holocaust survivor Olga Lengyel. In the fall of 1944, Olga was forced to board a cattle car bound for Auschwitz with her parents, her husband, and their two sons, yet she alone survived the war. -

EVA KOR (1934-2019) a Woman of Peace

Holocaust Survivor EVA KOR (1934-2019) A woman of peace. A woman of forgiveness. By Susan M. Brackney For decades, Eva Mozes Kor carried the weight of Auschwitz experiments in pursuit of a perfect Aryan race. After the 1945 with her. At the age of 10, her parents and her two older liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviet army, Eva and Miriam sisters were murdered there by the Nazis. The fact that she survived life in communist Romania, later immigrating and her identical twin sister survived only added to that to Israel in 1950 at the age of 16. Both served in the Israeli weight. But, in the end, it wasn’t what she carried but what army. In 1960, Eva met and married Mickey Kor, himself she finally chose to lay down that mattered most—to her and a Holocaust survivor. Although she spoke no English, she to those who will carry on her legacy. moved with him to Terre Haute, Indiana. Born in the village of Portz, Romania, in 1934, Eva and “My mom was considered somewhat of a pariah and an Miriam Mozes were among 3,000 twins Josef Mengele used in oddball here when I was younger,” recalls her son, Alex Kor, a podiatrist with Witham Health Services in Lebanon, Indiana. “People made fun of her because they didn’t know her story. And she didn’t really know how to succinctly represent what had happened to her.” In Indiana, Kor endured years of anti-Semitic Halloween pranks and was the target of a hate crime. -

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters Ingrid Lewis B.A.(Hons), M.A.(Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of PhD June 2015 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Debbie Ging I hereby declare that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copywright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 12210142 Date: ii Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my most beloved parents, Iosefina and Dumitru, and to my sister Cristina I am extremely indebted to my supervisor, Dr. Debbie Ging, for her insightful suggestions and exemplary guidance. Her positive attitude and continuous encouragement throughout this thesis were invaluable. She’s definitely the best supervisor one could ever ask for. I would like to thank the staff from the School of Communications, Dublin City University and especially to the Head of Department, Dr. Pat Brereton. Also special thanks to Dr. Roddy Flynn who was very generous with his time and help in some of the key moments of my PhD. I would like to acknowledge the financial support granted by Laois County Council that made the completion of this PhD possible. -

El Médico-Demonio Del Tercer Reich, Josef Mengele: “El Ángel De La Muerte” Ha Caído En Auschwitz

Universidad del Bío-Bío - Sistema de Bibliotecas - Chile Facultad de Educación y Humanidades Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Escuela de Pedagogía en Historia y Geografía EL MÉDICO-DEMONIO DEL TERCER REICH, JOSEF MENGELE: “EL ÁNGEL DE LA MUERTE” HA CAÍDO EN AUSCHWITZ. Tesis para optar al Título de Profesor de Educación Media en Historia y Geografía Autor: Fabián Esteban Retamal Arellano Profesor Guía: Dr. Félix Maximiano Briones Quiroz Chillán, 2013 Universidad del Bío-Bío - Sistema de Bibliotecas - Chile 2 Índice Agradecimientos………………………………………………………………………… 5 Introducción…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Marco Teórico…………………………………………………………………………... 7 Formulación del Problema…………………………………………………………….. 16 Hipótesis……………………………………………………………………………….... 17 Objetivos……………………………………………………………………………… 17-18 Metodología…………………………………………………………………………….. 18 Capítulo 1: CRECIMIENTO IDEOLOGICO Y ACADEMICO DE JOSEF MENGELE……………………………….. 20 1.1 La familia Mengele ………………………………………………………………... 20 1.1.1 El joven Josef …………………………………………………………………… 22 1.2 La Alemania de post Guerra ……………………………………………………... 23 1.2.1 El Tratado de la Vergüenza de 1919 …………………………………………... 24 1.2.2 Adolf Hitler y el Nacionalsocialismo …………………………………………... 27 1.3 Los ideólogos de la Teoría Racial ………………………………………………... 30 1.3.1 Theodor James Mollison………………………………………………………... 31 1.3.2 Eugen Fischer …………………………………………………………………... 31 1.3.3 Ottmar Freiherr von Verschuer ………………………………………………… 33 1.4 El desenfrenado camino académico del “Ángel de la muerte”…………………………………………………………….... 34 1.4.1 Filosofía y Antropología en la Universidad de Münich………………………………………………………………………. 34 Universidad del Bío-Bío - Sistema de Bibliotecas - Chile 3 1.4.2 Medicina en la Universidad de Frankfurt ……………………………………… 38 1.5 El pacto total con la Schutzstaffel: Mengele miembro de la Waffen SS………………………………………………………..... 41 1.5.1 Las SS de Heinrich Himmler …………………………………………………... 41 1.5.2 Mengele el médico de la Elite Nacionalsocialista ……………………………... 43 Capitulo 2: DR. MENGELE: SU PASO POR EL “LABORATORIO DEL INFIERNO”…………………………………. -

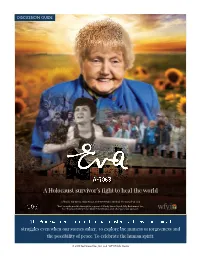

Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE A Holocaust survivor’s fight to heal the world A film by Ted Green, Mika Brown and WFYI Public Media | TheStoryofEva.com “Eva” is made possible through the support of Cindy Simon-Skjodt, Lilly Endowment Inc., the Efroymson Family Fund, Glick Philanthropies and other generous sponsors. ThisThis gguideuide isis anan invitationinvitation toto dialogue.dialogue. ToTo listen.listen. ToTo discoverdiscover oourur ssharedhared strugglesgl even whenh our storiest i ddiffer.iff T To explorel t hthef fullnessll foff forgivenessgi and the possibility of peace. To celebrate the human spirit. © 2018Ted Green films, LLC and WFYI Public Media DISCUSSION GUIDE Eva Mozes Kor At 10, she survived experiments by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. At 50, she helped launch the biggest manhunt in history. Now 84, after decades of pain and anger, she travels the world to promote what her life journey has taught: HOPE. HEALING. HUMANITY. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE FILM AND CONVERSATION Film Synopsis ......................................................................................................................3 The Production Team ............................................................................................................5 Who Might Benefit from this Discussion ..................................................................................7 Our Hope for Your Discussion................................................................................................7 FACILITATOR TIPS and GUIDANCE Facilitating a Film-based -

California State University, San Bernardino Journal of History

HISTORY IN THE MAKING California State University, San Bernardino Journal of History Volume Fourteen 2021 Alpha Delta Nu Chapter, Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society History in the Making is an annual publication of the California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB) Alpha Delta Nu Chapter of the Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society, and is sponsored by the History Department and the Instructionally Related Programs at CSUSB. Issues are published at the end of the spring quarter of each academic year. Phi Alpha Theta’s mission is to promote the study of history through the encouragement of research, good teaching, publication and the exchange of learning and ideas among historians. The organization seeks to bring students, teachers and writers of history together for intellectual and social exchanges, which promote and assist historical research and publication by our members in a variety of ways. Copyright © 2021 Alpha Delta Nu, California State University, San Bernardino. Original cover art “World War II Plane Dropping Ammunition for the Chinese Nationalists” by Brittany Mondragon, medium: acrylic on canvas, Copyright © 2021 History in the Making History in the Making Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xv Editorial Staff .............................................................................. xvi Articles The Weight of Silk: An Exploratory