An Interview with Eva Mozes-Kor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNEY to AUSCHWITZ 2018 June 23 - July 1 Walk in the Steps of Eva Kor, Holocaust Survivor and Forgiveness Advocate

JOURNEY TO AUSCHWITZ 2018 June 23 - July 1 Walk in the steps of Eva Kor, Holocaust survivor and forgiveness advocate Join CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center for an extraordinary experience as we travel to Auschwitz with survivor Eva Mozes Kor. As we walk in her footsteps, you will hear Eva’s firsthand account of her arrival at Auschwitz, separation from her family, experimentation by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, the struggle for survival, and her and her twin sister Miriam’s liberation by the Soviet Army on January 27, 1945. “Complete” Trip Package: $3900 Preliminary Itinerary includes: • Economy-class flight from Chicago • Staying in beautiful and historic Krakow O’Hare airport • Visit to the Wieliczka Salt Mine • Hotel accommodations • Tour of Krakow’s Old Town, including Wawel • Land transportation Castle, St. Mary’s Church, and Market Square • Daily breakfast • Tour of the Jewish Quarter and Plaszow • Three lunches Memorial • Five evening meals • Tour of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz-Birkenau • Free day to explore on your own “Land” Trip Package: $2600 • Hotel accommodations Please complete all registration materials • Land transportation and return them to CANDLES with a • Daily breakfast • Three lunches $750 nonrefundable deposit to secure • Five evening meals your spot. Registration will remain open *With this option you arrange and purchase until March 14, 2018 or until capacity is your own travel to and from Poland full. Register online at www.candlesholocaustmuseum.org/trips or mail in registration forms to CANDLES Holocaust Museum. CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center 1532 South Third Street Terre Haute, IN 47802 +1.812.234.7881 [email protected] About CANDLES and Eva Kor By providing trip participants with an immersive experience in the historical setting of Auschwitz, we hope to foster powerful breakthroughs in awareness of our respective roles in creating a world based on hope, healing, respect, and responsibility. -

Project Deliverable Holocaust Background Text How Is It Possible That a Man with Such Hateful, Devastating Intentions Can Gain A

Project Deliverable Holocaust Background Text How is it possible that a man with such hateful, devastating intentions can gain as much power as Adolf Hitler did before and during World War II? It is a common belief that in order for people to follow a hateful leader, they must themselves be hateful people. However, it has been shown that that it not necessarily true and this is how Hitler was able to gain his power. In further research, it is understood that people did not necessarily agree with his anti-Semitism beliefs but rather agreed with his other beliefs and ignored his extreme anti-Semitism. [1] Despite losing a Presidential election in 1932, through this process, Hitler began to make a name for himself and gained political attention. However, it wasn't until he was appointed chancellor months later that he was able to start his rise to power. Even though Hitler freely expressed his strong distaste toward the Jews, it was his "powerful leadership, the promise of a reborn Germany, the interests of the common people, and above all, strong anti-Marxism" that made his leadership attractive to the German population. [1] In 1933, when Hitler was elected, there were only half a million Jews in all of Germany. This means that they accounted for less than one percent of the German population. Despite such a low population, the Jews heightened their visibility by high concentrations in certain cities and overrepresentation in certain businesses. "German Jews enjoyed freedom of religion and legal equality, including the right to vote. In contrast, Jews in Russia and Eastern Europe were still fleeing pogroms. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

EVA KOR (1934-2019) a Woman of Peace

Holocaust Survivor EVA KOR (1934-2019) A woman of peace. A woman of forgiveness. By Susan M. Brackney For decades, Eva Mozes Kor carried the weight of Auschwitz experiments in pursuit of a perfect Aryan race. After the 1945 with her. At the age of 10, her parents and her two older liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviet army, Eva and Miriam sisters were murdered there by the Nazis. The fact that she survived life in communist Romania, later immigrating and her identical twin sister survived only added to that to Israel in 1950 at the age of 16. Both served in the Israeli weight. But, in the end, it wasn’t what she carried but what army. In 1960, Eva met and married Mickey Kor, himself she finally chose to lay down that mattered most—to her and a Holocaust survivor. Although she spoke no English, she to those who will carry on her legacy. moved with him to Terre Haute, Indiana. Born in the village of Portz, Romania, in 1934, Eva and “My mom was considered somewhat of a pariah and an Miriam Mozes were among 3,000 twins Josef Mengele used in oddball here when I was younger,” recalls her son, Alex Kor, a podiatrist with Witham Health Services in Lebanon, Indiana. “People made fun of her because they didn’t know her story. And she didn’t really know how to succinctly represent what had happened to her.” In Indiana, Kor endured years of anti-Semitic Halloween pranks and was the target of a hate crime. -

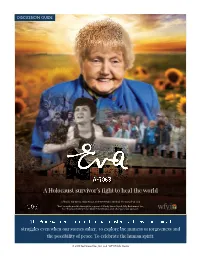

Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE A Holocaust survivor’s fight to heal the world A film by Ted Green, Mika Brown and WFYI Public Media | TheStoryofEva.com “Eva” is made possible through the support of Cindy Simon-Skjodt, Lilly Endowment Inc., the Efroymson Family Fund, Glick Philanthropies and other generous sponsors. ThisThis gguideuide isis anan invitationinvitation toto dialogue.dialogue. ToTo listen.listen. ToTo discoverdiscover oourur ssharedhared strugglesgl even whenh our storiest i ddiffer.iff T To explorel t hthef fullnessll foff forgivenessgi and the possibility of peace. To celebrate the human spirit. © 2018Ted Green films, LLC and WFYI Public Media DISCUSSION GUIDE Eva Mozes Kor At 10, she survived experiments by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. At 50, she helped launch the biggest manhunt in history. Now 84, after decades of pain and anger, she travels the world to promote what her life journey has taught: HOPE. HEALING. HUMANITY. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE FILM AND CONVERSATION Film Synopsis ......................................................................................................................3 The Production Team ............................................................................................................5 Who Might Benefit from this Discussion ..................................................................................7 Our Hope for Your Discussion................................................................................................7 FACILITATOR TIPS and GUIDANCE Facilitating a Film-based -

The Medical Madness of Nazi Germany

A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT FROM THE COLUMBIA HOLOCAUST EDUCATION COMMISSION • SUNDAY, APRIL 24, 2016 • VOLUME 3 Holocaust Remembered THE MEDICAL MADNESS OF NAZI GERMANY Experimentation, Ethics and Genetics 2 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT FROM THE COLUMBIA HOLOCAUST EDUCATION COMMISSION APRIL 24, 2016APRIL 24, 2016 Contributors Lilly Filler, M.D. Co-chair, Columbia Holocaust Madness then, madness now Education Commission Secretary, S.C. Council on the By Lilly Filler and wonderful medical care that you Holocaust offer the Midlands. t has become hard to remem- Lyssa Harvey, Ed.S The Columbia Holocaust Educa- ber a time when we did not Co-chair, Columbia Holocaust tion Commission is a volunteer or- Education Commission have to worry about terror- ganization created with remaining Teacher, therapist, artist ism, when the world seemed funds from the Holocaust Memorial, so large, when the USA was Charles Beaman dedicated on June 6, 2001, in down- CEO, Palmetto Health a very safe place, and when town Memorial Park on Gadsden the distances around the world were Allan Brett, M.D. Street. Professor of Clinical Medicine, Ilong. The Memorial lists the South USC School of Medicine Today, with a 24-hour news cycle Carolina Holocaust survivors and and live streaming of wars, terrorist F.K. Clementi, Ph.D. liberators. It educates the unin- Associate Professor of Jewish attacks, protests and demonstra- formed through an abbreviated Studies, USC tions, everything seems so close and timeline and a gripping pictorial Janice G. Edwards, M.S., CGC so personal. etching depicting scenes from the Clinical Professor and Director of Is this better Genetic Counseling Program, Holocaust. -

The Holocaust and Human Experimentation: the Nazi Approach to Medicine

Miller 1 Samantha Miller June 10th, 2020 HIST 461-07 Murphy The Holocaust and Human Experimentation: The Nazi Approach to Medicine The beginning months of 1945 marked the commencement of the swift downfall of the Nazi regime and the end of the tyrannical, oppressive ruling power it held over most of Europe for close to a decade. As Allied Forces invaded Nazi Germany and the remaining Nazi-occupied territories, they undoubtedly expected to encounter the incredible devastation that World War II had left upon most of the Western European continent, from toppled cities, to separated families, to the rising death toll. However, Allied soldiers would soon have to come face to face with another side-effect of the war, something unforeseen and unimaginable, even in their wildest dreams: the reality of concentration camps and the horrors that existed within. Upon arriving at any given concentration camp, all who passed through the iron gate, be that soldiers or prisoners, read the German phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei” as it was engraved, painted, or wielded into the sign above the entrance, providing the prisoners with the illusion that their hard work would eventually ensure their freedom. Stepping inside the electrically-barbed barricades and stone walls, soldiers had to confront the horrendous conditions in which prisoners were forced to live: disease running rampant, extreme starvation, tediously pointless labor, overcrowding, and the mass executions carried out inside the on-site gas chambers. A member of the United States Army’s Third 8th Tank Battalion, Albin Irzyk, was a part of the liberation effort at the Buchenwald camp in April of 1945 and described his findings in ghastly detail, stating that what he saw “looked like bundles of ragged clothing in an elliptical circle. -

Teaching History

The Holocaust and Other Genocides Issue 153 / December 2013 This special edition is brought to you in collaboration with the 02 EDITORIAL 38 ELISABETH KELLEWAY, Institute of Education, University of London THOMAS SPILLANE AND 03 HA SECONDARY NEWS TERRY HAYDN ‘Never again’? Helping Year 9 04 TAMSIN LEYMAN AND think about what happened RICHARD HARRIS after the Holocaust and learning lessons from genocides Connecting the dots: helping Year This edition has been generously supported by the Claims 9 to debate the purposes Conference as part of the IOE of Holocaust and genocide 45 NEW, NOVICE OR NERVOUS? Beacon Schools programme. education 46 MARK GUDGEL 11 DARIUS JACKSON A short twenty years: meeting the ‘But I still don’t get why the Jews’: challenges facing teachers who using cause and change to answer bring Rwanda into the classroom pupils’ demand for an overview of antisemitism 56 JAMES WOODCOCK History, music and law: 18 LEANNE JUDSON commemorative cross-curricularity ‘It made my brain hurt, but in a good way’: helping Year 9 60 POLYCHRONICON learn to make and to evaluate Dan Stone explanations for the Holocaust 62 ANDREW PRESTON 26 IOE UPDATE An authentic voice: perspectives Rebecca Hale on the value of listening to survivors of genocide 30 ALISON STEPHEN Patterns of genocide: can we 72 MOVE ME ON educate Year 9 in genocide The Historical Association prevention? 76 MUMMY, MUMMY... 59a Kennington Park Road London SE11 4JH Telephone: 020 7735 3901 Fax: 020 7582 4989 PRESIDENT Professor Jackie Eales DEPUTY PRESIDENT Chris Culpin EDITED BY Publication of a contribution in Teaching HONORARY TREASURER Richard Walker Arthur Chapman, Institute of Education, University of London History does not necessarily imply the Historical HONORARY SECRETARY Dr Trevor James Paul Salmons, Institute of Education, University of London Association’s approval of the opinions expressed CHIEF EXECUTIVE Rebecca Sullivan Christine Counsell, University of Cambridge Faculty of Education in it. -

Vergebung Macht Frei-Forgiveness Liberates: the Need for Restorative Justice in the Resolution of Holocaust-Like Crimes

Vergebung Macht Frei-Forgiveness Liberates: The Need for Restorative Justice in the Resolution of Holocaust-like Crimes KAITLYN N. PYTLAK* I. INTRODUCTION Ii. BACKGROUND A. Portraitof a Heroine in the Restorative Justice System Eva Mozes Kor: Victim and Survivor of the Mengele Experiments Friendof Forgiveness:Eva Mozes Kor's Experience with Restorative Justice B. Inadequate Measures: Current Methods Used to Resolve Holocaust-like Crimes 1. Not Enough: A BriefLook at the Nuremberg Trials 2. Deserving Destiny: The Demjanjuk Precedent C. A Viable New Approach: Restorative Justice and the ForgivingResolution m. ANALYSIS A. Instituting Restorative Justice: Overcoming the Inadequacies of the Litigation in Holocaust-like Situations 1. Gives Victims Opportunity to Face Oppressors While MaintainingControl 2. Provides a Forumfor Open Dialoguebetween Victims and Oppressors 3. Transforms the Lives ofAll CooperatingParties B. Applicability of Restorative Justice to Holocaust-like Situations (i.e. Maritime Disasters,Attacks of Mass Violence, etc.) 1. Maritime Disasters 2. Attacks of Mass Violence Attorney at Flaherty Sensabaugh Bonasso PLLC in Charleston, West Virginia; Former Executive Notes Editor, West Virginia Law Review Volume 118; J.D. West Virginia University College of Law; B.A. Wheeling Jesuit University. The Author would like to thank her parents, siblings, and family for their eternal love and support. Without you, I would be nothing. Lastly, and most importantly, the Author wishes to thank Eva Mozes Kor for sharing her incredible journey of forgiveness with the world. Don't forget, forgiveness liberates! 219 OHIO STATE JOURNAL ON DISPUTE RESOLUTION [Vol. 32:2 2017] IV. CONCLUSION "I believe with every fib[er] of my being that every human being has the right to live without the pain of the past. -

Newsletter July 2019 Message from the HERC Volume 8 • No

Newsletter July 2019 Message from the HERC Volume 8 • No. 4 The World has Lost Another Light he world has lost another light. Miriam became a nurse. In 1960, order to bring the story of Mengele TRomanian-born Holocaust Eva married an American tourist to an international audience. She survivor Eva Mozes Kor, who and concentration camp survivor, also wanted to find other twin founded the Candles Museum in Michael Kor. They settled in Terre survivors of Mengele. To facilitate Indiana and devoted her life to Haute, Indiana. In 1993, Miriam both of these goals, she founded Holocaust awareness, was 85 when died from the consequences of the Candles Museum in Terre she passed away on July 4, 2019, Haute and dedicated her life to during a visit to Auschwitz. Holocaust education. Eva was ten years old when the In 1993, Eva met with Hans Russians liberated Auschwitz in Munch, a Nazi doctor who was the January 1945, and she is spotted in only person acquitted at the the Russian photos of the children continued on page 2 that they found there. Eva and her sister Miriam were among the multitudes of children Inside this Edition . experimented on by Dr. Mengele. After liberation, Eva and Miriam Mengele’s experiments. Eva World Has Lost Another Light . 1 went to Israel and joined a kibbutz survived and devoted her life to Eva Kor continued . 2 made up mostly of orphans. They Holocaust awareness. The 1978 TV HERC Book Dicussion . 3 both joined the Israeli army in mini-series, “Holocaust” motivated 1952. Eva studied drafting and Eva to speak of her experiences in Rememberance Dinner . -

The Firebombing of the Terre Haute Holocaust Museum a Hoosier Community Responds to an Assault on Collective Memory

The Firebombing of the Terre Haute Holocaust Museum A Hoosier Community Responds to an Assault on Collective Memory WILLIAM B. PICKETT he events of a night in November 2003 in Terre Haute, Indiana, re- T minded local citizens that historical truth, though often unsettling, is also precious-and that its preservation keeps us in contact with es- sential principles of human dignity and morality. That night an arsonist destroyed a small museum dedicated to the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust. The identity and intent of the arsonist remains un- known, but it is doubtful that the response this violent act elicited was the one intended. In the days and weeks that followed, a sizeable group of citizens, including thousands of school children, came forward to of- fer support. Using newspaper articles, school fundraising activities, and electronic mail, they had within four months obtained donations sufficient to begin to rebuild the museum. By their spontaneous, posi- tive response to an act of hate, these citizens created a new and consid- erably larger awareness in their community of the importance of the museum and its founder, a Holocaust survivor. They also revealed an William B. Pickett is a professor of history at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Terre Haute. INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY, 100 (September 2004). 0 2004, Tiustees of Indiana University 244 INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY awareness of the nature and causes of genocide-something they had gained from a variety of sources, including books and articles, Hollywood films, television programs, the Internet, curricular reform in the schools, visits to a newly created national Holocaust museum, and by 2003, per- haps most important, from continued violent assaults on civil societies by terrorist groups and brutal regimes. -

Eva Kor Terre Haute, Vigo County January 31 –

Eva Kor Terre Haute, Vigo County January 31 – Eva Mozes Kor is a Holocaust survivor, a forgiveness advocate, and public speaker. Eva Mozes was born in 1934 in the village of Portz, Romania. Though the Mozes family were landowners and farmers, the family lived under the shadow of the Nazi takeover of Germany and the everyday experience of prejudice against the Jews. In 1944, the family was transported to the regional ghetto and then to the Auschwitz death camp. Kor lost both parents and two older sisters, and then suffered through numerous experiments, along with her twin sister, Miriam, as part of Dr. Josef Mengele’s infamous experiments on twins. The concentration camp was liberated in 1945. Later, both girls moved to Israel by 1950 to be raised by family. She married and moved to Terre Haute where she entered Indiana State University, earning a degree at the age of 56. Kor has spent her lifetime educating about the Holocaust. In 1995 she created CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Terre Haute in memory of Miriam who died in 1993. The museum was destroyed in 2003 by arson. Through the generosity of local and national supporters, CANDLES rose from the ashes and erected a new building. By April of 2005, CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center was reopened to the public. A 2005 recipient of the Indiana Commission for Women’s Torchbearer Awards, she denies being a victim despite all she has been through. “Don’t pity me. Envy me,” she stated. “I survived and I function and I have overcome unbelievable evil.” ____ For more information about Eva Kor, go to: http://www.candlesholocaustmuseum.org/about/eva-kor.htm.