Space Policies for the New Space Age: Competing on the Final Economic Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Space Exploration Strategy Group International Space Exploration

INTERNATIONAL SPACE EXPLORATION STRATEGY GROUP INTERNATIONAL SPACE EXPLORATION. STRATEGY GROUP ADVANCING THE EXPLORATION FRONTIER For the last forty years, human In recent years multiple reports define exploration in the coming space exploration has made have recommended international decades. significant progress through partners come together for The group will bring together the international collaboration. The strategic planning activities. interests of all human spaceflight Apollo-Soyuz Test Project and However, many national partners, rather than national Shuttle-Mir Programs marked government planning activities interests subject to changing the end of the Space Race, are severely limited in their political influences. and advanced long duration consideration of international This project provides a unique spaceflight. The International partners. Furthermore, opportunity for current and Space Station (ISS) is now in its government and industry recent graduate student second decade as a continuously planners may not have access researchers to collaborate with occupied human outpost in Low- to the latest technologies being others from around the world. Earth Orbit (LEO). While we developed at leading research Most importantly, participants expect productive utilization of institutions around the world. will have the opportunity to ISS through at least 2020, there We believe an international influence the government and is currently no internationally graduate student working group industry decision makers that recognized program for human is well-suited to generate and define future human exploration exploration beyond LEO. communicate the ideas that will strategy. 3 INTERNATIONAL SPACE EXPLORATION. STRATEGY GROUP INTERNATIONAL SPACE EXPLORATION. STRATEGY GROUP LEADERSHIP Edward Crawley is President of the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech). -

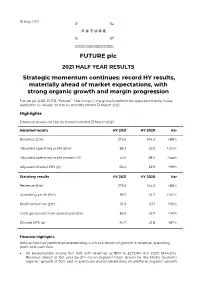

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

China Science and Technology Newsletter No. 14

CHINA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY NEWSLETTER Department of International Cooperation No.14 Ministry of Science and Technology(MOST), P.R.China July 25 2014 Special Issue: China’s Space Development Achievements and Prospects of China’s Space Development The 64th IAC Held in Beijing Shenzhou 10 Misson Successfully Accomplished Chang’e 3 Achieved Soft Landing on the Moon GF-1 Satellite - The First Satellite of CHEOS Achievements and Prospects of China’s Space Development Mr. Xu Dazhe, Chairman of China Aerospace Science in 1970 marked the start of China entering into space and and Technology Corporation (CASC) delivered a speech exploring the universe. Due to substantial governmental at the 64th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) on support and promotion, China’s space industry developed September 23, 2013, sharing experiences gained in the quite fast and has made world-known achievements. development of China’s space industry with international As the leader in China’s space sector, CASC is colleagues. assigned to develop, manufacture and test launch OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENTS MADE BY vehicles, manned spaceships, various satellites and CHINA’S SPACE INDUSTRY other spacecraft for major national space programs such as China’s Manned Space Program, China’s Lunar China’s space programs have had 57 years of Exploration Program, BeiDou Navigation Satellite development since the 1950s. The successful launch of System, and China’s High-Resolution Earth Observation China’s first artificial satellite Dongfanghong 1 (DFH-1) Monthly-Editorial Board:Building A8 West, Liulinguan Nanli, Haidian District, Beijing 100036, China Contact: Prof.Zhang Ning E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] http://www.caistc.com System. -

Lunar Space Elevator Infrastructure

Lunar Space Elevator Infrastructure A Cost Saving Approach to Human Spaceflight within a 15-year Constrained NASA Budget White Paper Submitted at the Open Invitation of the National Research Council 2013 Lunar Space Elevator Infrastructure In Response to the National Research Council’s Study on the Benefits, Challenges and Ramifications of America’s Human Spaceflight Program. LiftPort Group presents a Cost-Effective Approach to Human Spaceflight within a 15-year Constrained NASA Budget. | MICHAEL LAINE – PRESIDENT, LIFTPORT GROUP | CHARLES RADLEY MSC., – ADVISOR, LIFTPORT GROUP | MARSHALL EUBANKS MSC., – ADVISOR, LIFTPORT GROUP | JEROME PEARSON MSC., – ADVISOR, LIFTPORT GROUP | PETER SWAN PHD., – ADVISOR, LIFTPORT GROUP | LEE GRAHAM (NASA – HIS VIEWS DO NOT REFLECT HIS EMPLOYER) | | 8 JULY 2013 | LIFTPORT GROUP | 1307 Dogwood Hill RD SW, Port Orchard, WA, 98366 | www.liftport.com | (862) 438-5383 | [email protected] LiftPort’s Lunar Space Elevator Infrastructure: Affordable Response to Human Spaceflight What are the important benefits provided to the United States and other countries by human spaceflight endeavors? The ability to place humans in space is exciting to the public, and demonstrates the technological maturity and stature of each spacefaring nation. Such a visible and peaceful demonstration of cutting edge technology fosters foreign policy by showing Page | 1 strength without engaging in conflicti. Human spaceflight sparks the imagination and serves an instinctive need to explore. Astronauts are ambassadors for all of humanity in a very personal way. Men and women in space suits inspire people – of all cultures and demographics – to achieve excellence, to believe in a common cause and to pursue a noble goal. -

Planetary Report Report

The PLANETARYPLANETARY REPORT REPORT Volume XXIX Number 1 January/February 2009 Beyond The Moon From The Editor he Internet has transformed the way science is On the Cover: Tdone—even in the realm of “rocket science”— The United States has the opportunity to unify and inspire the and now anyone can make a real contribution, as world’s spacefaring nations to create a future brightened by long as you have the will to give your best. new goals, such as the human exploration of Mars and near- In this issue, you’ll read about a group of amateurs Earth asteroids. Inset: American astronaut Peggy A. Whitson who are helping professional researchers explore and Russian cosmonaut Yuri I. Malenchenko try out training Mars online, encouraged by Mars Exploration versions of Russian Orlan spacesuits. Background: The High Rovers Project Scientist Steve Squyres and Plane- Resolution Camera on Mars Express took this snapshot of tary Society President Jim Bell (who is also head Candor Chasma, a valley in the northern part of Valles of the rovers’ Pancam team.) Marineris, on July 6, 2006. Images: Gagarin Cosmonaut Training This new Internet-enabled fun is not the first, Center. Background: ESA nor will it be the only, way people can participate in planetary exploration. The Planetary Society has been encouraging our members to contribute Background: their minds and energy to science since 1984, A dust storm blurs the sky above a volcanic caldera in this image when the Pallas Project helped to determine the taken by the Mars Color Imager on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shape of a main-belt asteroid. -

Enhanced Orbit Determination for Beidou Satellites with Fengyun-3C Onboard GNSS Data

GPS Solut DOI 10.1007/s10291-017-0604-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Enhanced orbit determination for BeiDou satellites with FengYun-3C onboard GNSS data 1,2 1 1 3 3 Qile Zhao • Chen Wang • Jing Guo • Guanglin Yang • Mi Liao • 1 1,2 Hongyang Ma • Jingnan Liu Received: 3 September 2016 / Accepted: 27 January 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract A key limitation for precise orbit determination (Root Mean Square) of overlapping orbit differences of BeiDou satellites, particularly for satellites in geosta- (OODs) is 2.3 cm for GPS-only solution. The 3D RMS of tionary orbit (GEO), is the relative weak geometry of orbit differences between BeiDou-only and GPS-only ground stations. Fortunately, data from a low earth orbiting solutions is 15.8 cm. Also, precise orbits and clocks for satellite with an onboard GNSS receiver can improve the BeiDou satellites were determined based on 97 global geometry of GNSS orbit determination compared to using (termed GN) or 15 regional (termed RN) ground stations. only ground data. The Chinese FengYun-3C (FY3C) Furthermore, also using FY3C onboard BeiDou data, two satellite carries the GNSS Occultation Sounder equipment additional sets of BeiDou orbit and clock products are with both dual-frequency GPS (L1 and L2) and BeiDou determined with the data from global (termed GW) or (B1 and B2) tracking capacity. The satellite-induced vari- regional (termed RW) stations. In general, the OODs ations in pseudoranges have been estimated from multipath decrease for BeiDou satellites, particularly for GEO observables using an elevation-dependent piece-wise linear satellites, when the FY3C onboard BeiDou data are added. -

Mir-125 in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis

Leukemia (2012) 26, 2011–2018 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/12 www.nature.com/leu SPOTLIGHT REVIEW MiR-125 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis L Shaham1,2, V Binder3,4,NGefen1,5, A Borkhardt3 and S Izraeli1,5 MiR-125 is a highly conserved microRNA throughout many different species from nematode to humans. In humans, there are three homologs (hsa-miR-125b-1, hsa-miR-125b-2 and hsa-miR-125a). Here we review a recent research on the role of miR-125 in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Its high expression in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) enhances self-renewal and survival. Its expression in specific subtypes of myeloid and lymphoid leukemias provides resistance to apoptosis and blocks further differentiation. A direct oncogenic role in the hematopoietic system has recently been demonstrated by several mouse models. Targets of miR-125b include key proteins regulating apoptosis, innate immunity, inflammation and hematopoietic differentiation. Leukemia (2012) 26, 2011–2018; doi:10.1038/leu.2012.90 Keywords: microRNA; hematopoiesis; hematological malignancies; acute myeloid leukemia; acute lymphoblastic leukemia MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are 21–23-nucleotide non-coding RNAs that nucleotides with the seed region of miR-125b (ebv-miR-BART21-5p, have crucial roles in fundamental biological processes by ebv-miR-BART8 and rlcv-miR-rL1-25). In humans, as in most of the regulating the levels of multiple proteins. They are transcribed genomes, there are two paralogs (hsa-miR-125b-1 on chromosome as primary miRNAs and processed in the nucleus by the RNase III 11 and hsa-miR-125b-2 on chromosome 21), coding for the same endonuclease DROSHA to liberate 70-nucleotide stem loops, the mature sequence. -

INTRODUCTION to U.S. Export Controls for the Commercial Space Industry

INTRODUCTION TO U.S. Export Controls for the Commercial Space Industry 2nd Edition – November 2017 Department of Federal Aviation Commerce Administration This publication was prepared by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce and the Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation. For additional information, questions, or comments, please visit our websites: www.space.commerce.gov ast.faa.gov IMAGE CREDITS Cover: Spaceflight Industries, Inc. Page 2: Blue Origin Page 12: NASA/Orbital ATK Page 32: Mobilus In Mobili Page 50: Planet Page 58: SSL Page 62: Spire Table of Contents PURPOSE ......................................................................1 SECTION 1: BACKGROUND ...................................................2 1.1 Export Control 101 ........................................................4 1.1.1 Definitions: Exports, Deemed Exports, and Re-exports .................4 1.1.2 The Reasons for Controls ................................................4 1.1.3 Regulations and Responsible Departments .............................5 1.1.4 Multilateral Commitments ..............................................7 1.2 What’s Changed Under Export Control Reform .........................8 1.2.1 Satellite Export Control Reform .........................................8 1.2.2 Major Process Changes under Export Control Reform ..................9 SECTION 2: UNDERSTANDING THE CONTROL LISTS AND HOW THEY WORK ......................................................12 2.1 Overview .................................................................14 -

The Artemis Accords: Employing Space Diplomacy to De-Escalate a National Security Threat and Promote Space Commercialization

American University National Security Law Brief Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 5 2021 The Artemis Accords: Employing Space Diplomacy to De-Escalate a National Security Threat and Promote Space Commercialization Elya A. Taichman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/nslb Part of the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Elya A. Taichman "The Artemis Accords: Employing Space Diplomacy to De-Escalate a National Security Threat and Promote Space Commercialization," American University National Security Law Brief, Vol. 11, No. 2 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/nslb/vol11/iss2/5 This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University National Security Law Brief by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Artemis Accords: Employing Space Diplomacy to De-Escalate a National Security Threat and Promote Space Commercialization Elya A. Taichman* “Those who came before us made certain that this country rode the first waves of the industrial revolutions, the first waves of modern invention, and the first wave of nuclear power, and this generation does not intend to founder in the backwash of the coming age of space. We mean to be a part of it—we mean to lead it. For the eyes of the world now look into space, to the Moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace. -

Kennedy's Quest: Leadership in Space

Kennedy’s Quest: Leadership in Space Overview Topic: “Space Race” Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: US History Time Required: One class period. Goals/Rationale: The decision by the Kennedy Administration to make a manned lunar landing the major goal of the US space program derived from political as well as scientific motivations. In this lesson plan, students do a close reading of four primary sources related to the US space program in 1961, analyzing how and why public statements made by the White House regarding space may have differed from private statements made within the Kennedy Administration. Essential Questions: How was the “Space Race” connected to the Cold War? How and why might the White House communicate differently in public and in private? How might the Administration garner support for their policy? Objectives Students will be able to: analyze primary sources, considering the purpose of the source, the audience, and the occasion. analyze the differences in the tone or content of the primary sources. explain the Kennedy Administration’s arguments for putting a human on the Moon by the end of the 1960s. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National History Standards US History, Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s) Standard 2A: The student understands the international origins and domestic consequences of the Cold War. Historical Thinking Skills Standard 2: Historical Comprehension Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage. Appreciate historical perspectives . Historical Thinking Skills Standard 4: Historical Research Capabilities Support interpretations with historical evidence. Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Frameworks USII [T.5] 1. Using primary sources such as campaign literature and debates, news articles/analyses, editorials, and television coverage, analyze the important policies and events that took place during the presidencies of John F. -

NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus

NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus NASAs Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus Committee on NASAs Strategic Direction Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu PREPUBLICATION COPYSUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study is based on work supported by Contract NNH10CC48B between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agency that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-XXXXX-X International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-XXXXX-X Copies of this report are available free of charge from: Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences National Research Council 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, NW, Keck 360, Washington, DC 20001; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313; http://www.nap.edu. -

Financial Infrastructure

CONFIDENTIAL FOR RESTRICTED USE ONLY (NOT FOR USE BY THIRD PARTIES) Public Disclosure Authorized FINANCIAL SECTOR ASSESSMENT PROGRAM Public Disclosure Authorized RUSSIAN FEDERATION FINANCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE TECHNICAL NOTE JULY 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized This Technical Note was prepared in the context of a joint World Bank-IMF Financial Sector Assessment Program mission in the Russian Federation during April, 2016, led by Aurora Ferrari, World Bank and Karl Habermeier, IMF, and overseen by Finance & Markets Global Practice, World Bank and the Monetary and Capital Markets Department, IMF. The note contains technical analysis and detailed information underpinning the FSAP assessment’s findings and recommendations. Further information on the FSAP program can be found at www.worldbank.org/fsap. THE WORLD BANK GROUP FINANCE & MARKETS GLOBAL PRACTICE Public Disclosure Authorized i TABLE OF CONTENT Page I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 15 III. Payment and Settlement Systems ............................................................................. 16 A. Legal and regulatory framework .......................................................................... 16 B. Payment system landscape .................................................................................... 18 C. Systemically important payment systems