Endogenous Opioid Analgesia in Peripheral Tissues and the Clinical Implications for Pain Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Advice Concerning the Addition of Certain Pharmaceutical Products

U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Daniel R. Pearson, Chairman Shara L. Aranoff, Vice Chairman Jennifer A. Hillman Stephen Koplan Deanna Tanner Okun Charlotte R. Lane Robert A. Rogowsky Director of Operations Karen Laney-Cummings Director of Industries Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Advice Concerning the Addition of Certain Pharmaceutical Products and Chemical Intermediates to the Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States Investigation No. 332--476 Publication 3883 September 2006 This report was prepared principally by Office of Industries Philip Stone, Project Leader With assistance from Elizabeth R. Nesbitt Primary Reviewers David G. Michels, Office of Tariff Affairs and Trde Agreements, John Benedetto, and Nannette Christ, Office of Economics Administrative Support Brenda F. Carroll Under the direction of Dennis Rapkins, Chief Chemicals and Textiles Division ABSTRACT Under the Pharmaceutical Zero-for-Zero Initiative, which entered into force in 1995, the United States and its major trading partners eliminated tariffs on many pharmaceuticals, their derivatives, and certain chemical intermediates used to make pharmaceuticals. The U.S. list of pharmaceutical products and chemical intermediates eligible for duty-free treatment under the agreement is given in the Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States. The Pharmaceutical Appendix is periodically updated to provide duty relief for additional such products, including newly developed pharmaceuticals. This report provides advice on the third update to the agreement, in which approximately 1,300 products are proposed to receive duty-free treatment. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,708.371 B2 Kessler Et Al

USOO9708371B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,708.371 B2 Kessler et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul.18, 2017 (54) TREATMENTS FOR GASTROINTESTINAL 5,654,278 A 8/1997 Sorensen DSORDERS 5,904,935 A 5/1999 Eckenhoff et al. 6,068,850 A 5, 2000 Stevenson et al. 6,124,261 A 9, 2000 Stevenson et al. (75) Inventors: Marco Kessler, Danvers, MA (US); 6,541,606 B2 4/2003 Margolin et al. Angelika Fretzen, Somerville, MA 6,734,162 B2 5/2004 Van Antwerp (US); Hong Zhao, Lexington, MA 6,828.303 B2 12/2004 Kim et al. (US); Robert Solinga, Brookline, MA 36.3% E: 1339. SN. (US); Vladimir Volchenok, Waltham, 7,056,942- - - B2 6/2006 HildesheimOK et al. MA (US) 7,141,254 B2 11/2006 Bhaskaran et al. 7,304,036 B2 * 12/2007 Currie .................. CO7K 14,245 (73) Assignee: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 514,122 Cambridge, MA (US) 7.351,798 B2 4/2008 Margolin et al. 7,371,727 B2 5/2008 Currie et al. (*)c Notice:- r Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 7,704,9477,494,979 B2 4/20102/2009 Currie et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 7,745,409 B2 6/2010 Currie et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 364 days. (Continued) (21) Appl. No.: 14/239,178 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (22) PCT Filed: Aug. 17, 2012 JP 64-009938 1, 1989 JP 2003-2012.56 T 2003 (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2012/051289 (Continued) S 371 (c)(1), (2), (4) Date: Nov. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr

US008158152B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 17, 2012 (54) LYOPHILIZATION PROCESS AND 6,884,422 B1 4/2005 Liu et al. PRODUCTS OBTANED THEREBY 6,900, 184 B2 5/2005 Cohen et al. 2002fOO 10357 A1 1/2002 Stogniew etal. 2002/009 1270 A1 7, 2002 Wu et al. (75) Inventor: Nageswara R. Palepu. Mill Creek, WA 2002/0143038 A1 10/2002 Bandyopadhyay et al. (US) 2002fO155097 A1 10, 2002 Te 2003, OO68416 A1 4/2003 Burgess et al. 2003/0077321 A1 4/2003 Kiel et al. (73) Assignee: SciDose LLC, Amherst, MA (US) 2003, OO82236 A1 5/2003 Mathiowitz et al. 2003/0096378 A1 5/2003 Qiu et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2003/OO96797 A1 5/2003 Stogniew et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2003.01.1331.6 A1 6/2003 Kaisheva et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 1560 days. 2003. O191157 A1 10, 2003 Doen 2003/0202978 A1 10, 2003 Maa et al. 2003/0211042 A1 11/2003 Evans (21) Appl. No.: 11/282,507 2003/0229027 A1 12/2003 Eissens et al. 2004.0005351 A1 1/2004 Kwon (22) Filed: Nov. 18, 2005 2004/0042971 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. 2004/0042972 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. (65) Prior Publication Data 2004.0043042 A1 3/2004 Johnson et al. 2004/OO57927 A1 3/2004 Warne et al. US 2007/O116729 A1 May 24, 2007 2004, OO63792 A1 4/2004 Khera et al. -

Datasheet Inhibitors / Agonists / Screening Libraries a DRUG SCREENING EXPERT

Datasheet Inhibitors / Agonists / Screening Libraries A DRUG SCREENING EXPERT Product Name : Frakefamide Catalog Number : T11323L CAS Number : 188196-22-7 Molecular Formula : C30H34FN5O5 Molecular Weight : 563.62 Description: Frakefamide is a potent analgesic. It acts as a peripheral active μ-selective receptor agonist. Frakefamide is unable to penetrate the blood-brain-barrier and enter the central nervous system. Storage: 2 years -80°C in solvent; 3 years -20°C powder; Receptor (IC50) Others In vivo Activity Frakefamide yields a dose-dependent increase in morphine appropriate responding to 50% at the highest dose tested (10 μmol/kg) after infusion durations of 2 min. Whereas after 15 min infusions a maximum of 25% morphine appropriate responding was occasioned at 17.5 μmol/kg [1,2]. Reference 1. Modalen AO, et al. A novel molecule (frakefamide) with peripheral opioid properties: the effects on resting ventilation compared with morphine and placebo. Anesth Analg. 2005 Mar;100(3):713-7. 2. Swedberg MD, et al. Drug discrimination: A versatile tool for characterization of CNS safety pharmacology and potential for drug abuse. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2016 Sep-Oct;81:295-305. FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES ONLY. NOT FOR DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. Information for product storage and handling is indicated on the product datasheet. Targetmol products are stable for long term under the recommended storage conditions. Our products may be shipped under different conditions as many of them are stable in the short-term at higher or even room temperatures. We ensure that the product is shipped under conditions that will maintain the quality of the reagents. -

Duodenal Perforation in a Patient with Heroin Use

LETTER TO EDITOR Duodenal perforation in a patient with heroin use Opioid kullanýmý ile iliþkili duodenal perforasyon Ümit Haluk Yeþilkaya1, Yasin Hasan Balcýoðlu2, Mehmet Cem Ýlnem3 1M.D., 2M.D.,3Assoc. Prof., Department of Psychiatry, Bakirkoy Prof Mazhar Osman Training and Research Hospital for Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, Istanbul, Turkey 1https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8521-1613 2https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1336-1724 3https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4127-1627 SUMMARY ÖZET A number of vascular pathologies are attributed to the Yoðun opioid kullanýmý miyokardiyal enfarktüs, iskemik opiate exposure such as myocardial infarction, ischaemic inme ve gastrointestinal sistemin hipoperfüzyonu gibi stroke, and hypoperfusion of the gastrointestinal tract. bazý vasküler patolojilere sebep olur. Burada, bilinen her- Here we presented a 30-year-old male patient with no hangi bir iskemik veya gastrointestinal hastalýk öyküsü history of any ischemic or gastrointestinal disease known olmayan 30 yaþýnda bir erkek hastanýn 10 yýllýk yoðun to have 10-year opioid use and had suffered a duodenal opioid kullanýmý sonrasý meydana gelen duedonal per- perforation. Prolonged exposure of opioids may lead to forasyon vakasýný sunduk. Opioidlere uzun süre maruz hypersensitivity reactions, ischemia and hypoperfusion kalýnmasý hipersensitivite reaksiyonlarýna, iskemi ve and combination of these entities with opioid-related hipoperfüzyona neden olabilir. Ayrýca buna opioid ile gastrointestinal motility deficits could contribute to the iliþkili gastrointestinal motilite bozukluklarýnýn eklenmesi epithelial damage and perforation as a consequence. de epitel hasarýna ve perforasyona katkýda bulunabilir. The presence of ischemic events should be kept in mind Yoðun eroin kullanan kiþilerde gastrointestinal semptom- in the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms in people larýn varlýðýnda iskemik olaylarýn varlýðý akýlda tutul- using intensive heroin. -

Stembook 2018.Pdf

The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. -

Agonists of Guanylate Cyclase Useful for the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders, Inflammation, Cancer and Other Disorders

(19) TZZ ¥__T (11) EP 2 998 314 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 23.03.2016 Bulletin 2016/12 C07K 7/08 (2006.01) A61K 38/10 (2006.01) A61K 47/48 (2006.01) A61P 1/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 15190713.6 (22) Date of filing: 04.06.2008 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR • SHAILUBHAI, Kunwar HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL NO PL PT Audubon, PA 19402 (US) RO SE SI SK TR • JACOB, Gary S. New York, NY 10028 (US) (30) Priority: 04.06.2007 US 933194 P (74) Representative: Cooley (UK) LLP (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in Dashwood accordance with Art. 76 EPC: 69 Old Broad Street 12162903.4 / 2 527 360 London EC2M 1QS (GB) 08770135.5 / 2 170 930 Remarks: (71) Applicant: Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc. This application was filed on 21-10-2015 as a New York, NY 10170 (US) divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (54) AGONISTS OF GUANYLATE CYCLASE USEFUL FOR THE TREATMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS, INFLAMMATION, CANCER AND OTHER DISORDERS (57) The invention provides novel guanylate cycla- esterase. The gastrointestinal disorder may be classified se-C agonist peptides and their use in the treatment of as either irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, or ex- human diseases including gastrointestinal disorders, in- cessive acidity etc. The gastrointestinal disease may be flammation or cancer (e.g., a gastrointestinal cancer). -

Target and Suspect Screening of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Raw Water and Drinking Water from Europe and Asia

Water Research 198 (2021) 117099 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Water Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/watres What’s in the water? –Target and suspect screening of contaminants of emerging concern in raw water and drinking water from Europe and Asia ∗ Rikard Tröger a, , Hanwei Ren b, Daqiang Yin b, Cristina Postigo c, Phuoc Dan Nguyen d, Christine Baduel e, Oksana Golovko a,f, Frederic Been g, Hanna Joerss h, Maria Rosa Boleda i, Stefano Polesello j, Marco Roncoroni k, Sachi Taniyasu l, Frank Menger a, Lutz Ahrens a, Foon Yin Lai a, Karin Wiberg a a Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Box 7050, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden b Key Laboratory of Yangtze River Water Environment, Ministry of Education, College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai 20 0 092, China c Water, Environmental, and Food Chemistry Unit (ENFOCHEM), Department of Environmental Chemistry, Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research (IDAEA-CSIC), Carrer Jordi Girona 18-26, Barcelona, 08034, Spain d Centre Asiatique de Recherche sur l’Eau, Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology, 268 Ly Thuong Kiet, District 10; Vietnam National University of Ho Chi Minh City, Linh Trung Ward, Thu Duc District, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam e Université Grenoble Alpes, IRD, CNRS, Grenoble INP, IGE, 38 050 Grenoble, France f University of South Bohemia in Ceske Budejovice, Faculty of Fisheries and Protection of Waters, South Bohemian Research Center of Aquaculture -

Customs Tariff - Schedule

CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE 99 - i Chapter 99 SPECIAL CLASSIFICATION PROVISIONS - COMMERCIAL Notes. 1. The provisions of this Chapter are not subject to the rule of specificity in General Interpretative Rule 3 (a). 2. Goods which may be classified under the provisions of Chapter 99, if also eligible for classification under the provisions of Chapter 98, shall be classified in Chapter 98. 3. Goods may be classified under a tariff item in this Chapter and be entitled to the Most-Favoured-Nation Tariff or a preferential tariff rate of customs duty under this Chapter that applies to those goods according to the tariff treatment applicable to their country of origin only after classification under a tariff item in Chapters 1 to 97 has been determined and the conditions of any Chapter 99 provision and any applicable regulations or orders in relation thereto have been met. 4. The words and expressions used in this Chapter have the same meaning as in Chapters 1 to 97. Issued January 1, 2020 99 - 1 CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE Tariff Unit of MFN Applicable SS Description of Goods Item Meas. Tariff Preferential Tariffs 9901.00.00 Articles and materials for use in the manufacture or repair of the Free CCCT, LDCT, GPT, following to be employed in commercial fishing or the commercial UST, MXT, CIAT, CT, harvesting of marine plants: CRT, IT, NT, SLT, PT, COLT, JT, PAT, HNT, Artificial bait; KRT, CEUT, UAT, CPTPT: Free Carapace measures; Cordage, fishing lines (including marlines), rope and twine, of a circumference not exceeding 38 mm; Devices for keeping nets open; Fish hooks; Fishing nets and netting; Jiggers; Line floats; Lobster traps; Lures; Marker buoys of any material excluding wood; Net floats; Scallop drag nets; Spat collectors and collector holders; Swivels. -

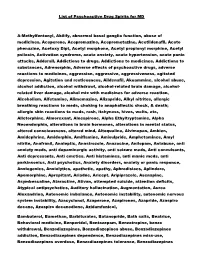

List of Psychoactive Drug Spirits for MD A-Methylfentanyl, Abilify

List of Psychoactive Drug Spirits for MD A-Methylfentanyl, Abilify, abnormal basal ganglia function, abuse of medicines, Aceperone, Acepromazine, Aceprometazine, Acetildenafil, Aceto phenazine, Acetoxy Dipt, Acetyl morphone, Acetyl propionyl morphine, Acetyl psilocin, Activation syndrome, acute anxiety, acute hypertension, acute panic attacks, Adderall, Addictions to drugs, Addictions to medicines, Addictions to substances, Adrenorphin, Adverse effects of psychoactive drugs, adverse reactions to medicines, aggression, aggressive, aggressiveness, agitated depression, Agitation and restlessness, Aildenafil, Akuammine, alcohol abuse, alcohol addiction, alcohol withdrawl, alcohol-related brain damage, alcohol- related liver damage, alcohol mix with medicines for adverse reaction, Alcoholism, Alfetamine, Alimemazine, Alizapride, Alkyl nitrites, allergic breathing reactions to meds, choking to anaphallectic shock, & death; allergic skin reactions to meds, rash, itchyness, hives, welts, etc, Alletorphine, Almorexant, Alnespirone, Alpha Ethyltryptamine, Alpha Neoendorphin, alterations in brain hormones, alterations in mental status, altered consciousness, altered mind, Altoqualine, Alvimopan, Ambien, Amidephrine, Amidorphin, Amiflamine, Amisulpride, Amphetamines, Amyl nitrite, Anafranil, Analeptic, Anastrozole, Anazocine, Anilopam, Antabuse, anti anxiety meds, anti dopaminergic activity, anti seizure meds, Anti convulsants, Anti depressants, Anti emetics, Anti histamines, anti manic meds, anti parkinsonics, Anti psychotics, Anxiety disorders, -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,957,025 B2 Owen (45) Date of Patent: Feb

USOO8957025B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,957,025 B2 Owen (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 17, 2015 (54) ENKEPHALIN ANALOGUES OTHER PUBLICATIONS (75) Inventor: Dafydd Rhys Owen, Cambridge, MA Waldhoer, et al., “Opioid Receptors”, Annu. Rev. Biochem., vol. 73, (Us) pp. 953-990 (2004). Bileviciute-Ljungar, et al., “Peripherally Mediated Antinociception (73) Assignee: P?zer Inc., New York, NY (US) of the p-Opioid Receptor Agonist 2-[(4,501-Epoxy-3-hydroxy-14B methoxy- 1 7-methylmorphinan-6B-yl)amino]acetic Acid (HS-731) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this after Subcutaneous and Oral Administration in rats With Car patent is extended or adjusted under 35 rageenan-Induced Hindpaw In?ammation”, JPET, vol. 317(1), pp. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 220-227 (2006). Gordon, et al., “Activation of P-glycoprotein ef?uX transport amelio (21) Appl. No.: 14/125,690 rates opioid CNS effects Without diminishing analgesia”, Drug Dis covery Today: Therapeutic Strategies, vol. 6(3), pp. 97-103 (2009). (22) PCT Filed: Jun. 29, 2012 He, et al., “Methadone Antinociception is Dependent on Peripheral Opioid Receptors”, Journal of Pain, vol. 10(4), pp. 369-379 (2009). (86) PCT No.: PCT/IB2012/053327 Koppert, et al., Peripheral Antihyperalgesic Effect of Morphine to Heat, but Not Mechanical, Stimulation in Healthy Volunteers after § 371 (00)’ Ultraviolet-B Irradiation, Anesthesia & Analgesia, vol. 88(1), pp. (2), (4) Date: Dec. 12, 2013 117-122 (1999). Oeltjenbruns, et al., “Peripheral Opioid Analgesia: Clinical Applica (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2013/008123 tions”, Current Pain and Headache Reports, vol.