THE INFLUENCE of the L. D. S. CHURCH in UTAH POLITICS, by Darwin Kay Craner a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah History Encyclopedia

POLYGAMY Polygamist prisoners, State Penitentiary, 1888 When establishing the LDS Church, Joseph Smith recorded numerous revelations he claimed to receive, often in answer to questions about the Bible, which are now included in the Doctrine and Covenants, part of the LDS canon. In answer to his question as to why many of the Old Testament leaders had more than one wife, Smith received what is now known as Section 132. Although the revelation was not recorded until 1843, Smith may have received it in the 1830s and married his first plural wife, Fanny Alger, in 1835. Polygamy was not openly practiced in the Mormon Church until 1852 when Orson Pratt, an apostle, made a public speech defending it as a tenet of the church. From 1852 until 1890, Mormon Church leaders preached and encouraged members, especially those in leadership positions, to marry additional wives. A majority of the Latter-day Saints never lived the principle. The number of families involved varied by community; for example, 30 percent in St. George in 1870 and 40 percent in 1880 practiced polygamy, while only 5 percent in South Weber practiced the principle in 1880. Rather than the harems often suggested in non-Mormon sources, most Mormon husbands married only two wives. The wives usually lived in separate homes and had direct responsibility for their children. Where the wives lived near each other, the husbands usually visited each wife on a daily or weekly basis. While there were the expected troubles between wives and families, polygamy was usually not the only cause, although it certainly could cause greater tension. -

A Study of the Utah Newspaper War, 1870-1900

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1966 A Study of the Utah Newspaper War, 1870-1900 Luther L. Heller Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Heller, Luther L., "A Study of the Utah Newspaper War, 1870-1900" (1966). Theses and Dissertations. 4784. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4784 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE UTAH NEWSPAPER WAR, 1870-1900 A Thesis Presented to the Department of Communications Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Luther L« Heller July 1966 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is sincerely grateful to a number of people for the inspiration and guidance he has received during his graduate study at Brigham Young University and in the writing of this thesis0 Because of the limited space, it is impossible to mention everyone. However, he wishes to express his appreciation to the faculty members with whom he worked in Communications and History for the knowledge which they have imparted* The author is especially indebted to Dr, Oliver R. Smith, chairman of the author's advisory committee, for the personal interest and patient counselling which have been of immeasurable value in the preparation of this thesis. -

The Political Thought and Activity of Heber J. Grant, Seventh President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1965 The Political Thought and Activity of Heber J. Grant, Seventh President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Loman Franklin Aydelotte Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Aydelotte, Loman Franklin, "The Political Thought and Activity of Heber J. Grant, Seventh President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints" (1965). Theses and Dissertations. 4492. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4492 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. f THE POLITICAL THOUGHT AND ACTIVITY OF HEBER J GRANT SEVENTH PRESIDENT OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS A thesis presented to the department of history brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by loman franklin aydelotte april 15 1965 this thesis by loman franklin aydelotte is accepted in its present form by the department of history of brigham0 young university as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of master of arts april 15 1965 minor committeetlitteeattee member vv acing chairman major depahnpient typed by nola B aydelotte -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

The Utah Taxpayer

The Volume Utah Taxpayer 34 JuJulyly 2009 2009 Number 7 Page 1 The Utah Taxpayer A Publication of the Utah Taxpayers Association 1578 West 1700 South♦Suite 201♦Salt Lake City, Utah 84104♦(801) 972-8814 July 2009 Articles 2009 Federal, State, and Local Tax Burden on 2009 Federal, State, and a Median-income Utah Family Local Taxes on a Mediam income Utah Family A median-income Utah household consisting of two parents and three children pays 24.2% of its income in direct federal, state, and local taxes, according to an analysis by the Utah Taxpayers Asso- My Corner – Iranian style ciation. A median-income Utah family with two parents and three children earns $63,074 in wages elections in Utah? and salary. Additionally, the family earned $5,474 in the form of employer-paid payroll taxes for a total income of $68,548. Highlights from the Taxes Now Conference The following chart illustrates the tax impact. These taxes do not include the taxes that businesses pay and pass The costs taxpayers pay on to their customers in because of UTOPIA Percent of Percent of the form of 2009 Taxes Amount Taxes Income RDAs: Corporate welfare higher prices, disguised as “economic to employees Social Security $7,821 47.1% 11.4% development” in the form of Sales tax 2,106 12.7% 3.1% reduced State income tax 1,967 11.9% 2.9% compensation, Medicare 1,829 11.0% 2.7% and to Property tax 1,347 8.1% 2.0% shareholders in Automobile taxes 922 5.6% 1.3% the form of Employment taxes 649 3.9% 0.9% reduced divi- dends and Excise taxes 306 1.8% 0.4% stock prices. -

Utah Symphony 2014-15 Fnishing Touches Series

University of Utah Professors Emeriti Club NEWSLETTER #7 2013/2014________________________________________________________________________________________________March_2014 April Luncheon Presentation Michael A. Dunn April 8, 2014, Tuesday, 12:15 pm Michael Dunn is the Chief Marketing Officer for Surefoot, a Park City, UT-based corporation that operates retail ski boot and specialty running stores in the United States and six foreign countries. Before joining Surefoot he was the General Manager of KUED Channel 7 where he directed the operations of this highly regarded PBS affiliate in Salt Lake City. Prior to his public television experience he founded and operated Dunn Communications, Inc, a Salt Lake City advertising agency and film production company for 16 years. Among his peer distinctions are a gold and silver medal from the New York Film Festival and four CLIOs--an award considered the “Oscar” of the advertising industry. In the spring of 2000 he was honored by the American Advertising Federation, Utah Chapter, as the inaugural recipient of the Advertising Professional of the Year Award. Michael spent 13 years as a senior writer and producer for Bonneville Communications where he worked on the highly acclaimed Homefront campaign for the LDS Church, and Fotheringham & Associates (now Richter 7). As a documentarian, he recently completed A Message to the World, a film about Salt Lake City’s post-Olympic environmental message to the citizens of Torino, Italy. Dunn graduated from the University of Utah where he received both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Communication. Professionally he earned an APR certificate from the Public Relations Society of America. Michael and his wife Linda have three children and three grand children. -

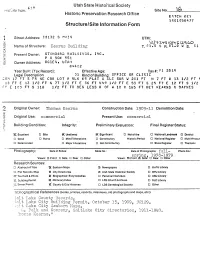

Structure/Site Information Form Spring. 1978-1979

Utah State'Historical Society Type: Site No. Historic Preservation Research Office KEY 1BQ1050437 Structure/Site Information Form Street Address: CO 132 S MAIN UTM: z V o Name of Structure: Kearns Building T. Ol.Q S R. 01.0 MS Present Owner: STANDARD BUILDINGS* INC P 0 BOX 951 Owner Address: OGDEN, UTAH Year Built (Tax Record): Effective Age: Tax#: j 251Q Legai Description 01 Kind of Building: OFFICE OR CLINIC COH 17 FT S PR NE COR LOT 8 BLK 65 PLAT A SLC SUR W 201 FT N 7 FT W 13 1/2 FT 10 FT E 13 1/2 FT N 77 1/2 FT E 36 FT N49 1/2 FT E 53 FT S 25 FT E 12 FT S 1/2 FT £ 103 FT S 118 1/2 FT TO'BEG LESS R OF W 10 X 165 FT BET KEARNS S OAYNES 9 Original Owner: Thomas Kearns Construction Date: 1909-11 Demolition Date: UJ 00 Original Use: commercial Present Use: commercial Building Condition: Integrity: Preliminary Evaluation: Final Register Status: K Excellent G Site E£ Unaltered K Significant O Not of the D National Landmark D District D Good D Ruins D Minor Alterations D Contributory Historic Period D National Register D Multi-Resoun a Deteriorated D Major Alterations D Not Contributory a Stale Register D Thematic Photography: Date of Slides: Slide No.: Date of Photographs: fall Photo No.: spring. 1978-1979 Views: D Front C Side D Rear D Other Views: IS Front /S Side D Rear G Other Research Sources: 3 Abstract of Title 1$£ Sanborn Maps !$ Newspapers D U of U Library £1 Plat Records/ Map £1 City Directories IS Utah State Historical Society D BYU Library Sf Tax Card & Photo fS Biographical Encyclopedias D Personal Interviews D USU Library S Building Permit US. -

Does Vote-By-Mail Cause Voters to Gather Information About Politics?∗

Does Vote-by-Mail Cause Voters to Gather Information About Politics?∗ James Szewczyk Department of Political Science Emory University [email protected] June 28, 2019 Abstract In this paper, I examine the effects of vote-by-mail on voter behavior and voter knowledge. I argue that vote-by-mail electoral systems result in a more informed electorate, because voters have additional time with their ballot and access to resources to conduct research about races on the ballot that they know nothing about. I present the results of two empirical studies that support this prediction. First, I find that all-mail elections in Utah cause a 6.368 percentage point decrease in straight ticket voting. This is con- sistent with the logic that voters spend more time with their ballots when voting by mail relative to when they are voting at a polling place. Second, I estimate the effects of vote-by-mail on voter knowledge using an original repeated cross-sectional survey that was fielded during the 2018 general election in California. The research design exploits the implementation of the California Voters Choice Act (VCA), which resulted in five counties in the state switching to an election system in which all voters in the counties are sent a mail-in ballot. I find that the VCA causes an increase in voter knowledge and an increase in time that voters spend gathering information about the election. However, the reform does not affect the prevalence of political discussion or levels of knowledge about the party identification and ideology of candidates. ∗I thank the MIT Election Data and Science Lab and the Madison Initiative of the William Flora Hewlett Foundation for generously funding this research. -

Joseph F. Smith: the Father of Modern Mormonism a Thesis

Joseph F. Smith: The Father of Modern Mormonism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By Alexander Reid Harrison B.S., Brigham Young University Idaho, 2010 2014 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Dec 13, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Alexander Reid Harrison ENTITLED Joseph F Smith: The Father of Modern Mormonism BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities ____________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Thesis Director Committee on ____________________ Final Examination Valerie L. Stoker, Ph.D. Director, Master of Humanities Program ____________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. ____________________ Jacob Dorn, Ph.D. ____________________ Nancy G. Garner, Ph.D. _____________________ Robert E. W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Harrison, Alexander Reid. M.H. Department of Humanities, Wright State University, 2014. Joseph F. Smith: The Father of Modern Mormonism Joseph F. Smith (1838-1918) was the father of modern Mormonism. Nephew of the founding Prophet, President Joseph Smith Jr. (1805-1844), Joseph F. Smith was the sixth president of the Mormon Church. During his presidency (1901-1918), he redefined Mormonism. He helped change the perception of what a Mormon was, both inside and outside the faith. He did so by organizing the structure of the faith theologically, historically, ideologically, and institutionally. In doing this, he set the tone for what Mormonism would become, and set a standard paradigm for the world of what a Mormon is. Joseph F. -

No. 17-15589 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS

Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10404479, DktEntry: 113, Page 1 of 35 No. 17-15589 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT STATE OF HAWAII, ET AL., Plaintiffs/Appellees v. DONALD J. TRUMP, ET AL., Defendants/Appellants. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR HAWAII THE HONORABLE DERRICK KAHALA WATSON, DISTRICT JUDGE CASE NO. 1:17-CV-00050-DKW-KSC AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF SCHOLARS OF AMERICAN RELIGIOUS HISTORY & LAW IN SUPPORT OF NEITHER PARTY ANNA-ROSE MATHIESON BEN FEUER CALIFORNIA APPELLATE LAW GROUP LLP 96 Jessie Street San Francisco, California 94105 (415) 649-6700 ATTORNEYS FOR AMICI CURIAE SCHOLARS OF AMERICAN RELIGIOUS HISTORY & LAW Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10404479, DktEntry: 113, Page 2 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................................................... ii INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE ............................................................. 1 STATEMENT OF COMPLIANCE WITH RULE 29 ................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 5 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................... 7 I. The History of Religious Discrimination Against Mormon Immigrants Demonstrates the Need for Vigilant Judicial Review of Government Actions Based on Fear of Religious Minorities ............................................... 7 A. Mormons Were the Objects of Widespread Religious Hostility in the 19th Century ....................... -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

RICK GRUNDER — BOOKS Mormon List Sixty-Six

RICK GRUNDER — BOOKS Box 500, Lafayette, New York 13084-0500 – (315) 677-5218 www.rickgrunder.com ( email: [email protected] ) JANUARY 2010 Mormon List Sixty-Six NO-PICTURES VERSION, for dial-up Internet Connections This is my first page-format catalog in nearly ten years (Mormon List 65 was sent by post during August 2000). While only a .pdf document, this new form allows more illustrations, as well as links for easy internal navigation. Everything here is new (titles or at least copies not listed in my offerings before). Browse like usual, or click on the links below to find particular subjects. Enjoy! ________________________________________ LINKS WILL NOT WORK IN THIS NO-PICTURES VERSION OF THE LIST. Linked References below are to PAGE NUMBERS in this Catalog. 1830s publications, 10, 21 Liberty Jail, 8 polygamy, 31, 50 Babbitt, Almon W., 18 MANUSCRIPT ITEMS, 5, 23, 27, re-baptism for health, 31 Book of Mormon review, 13 31, 40, 57, 59 Roberts, B. H., 32 California, 3 map, 16 Sessions family, 50 Carrington, Albert, 6 McRae, Alexander, 7 Smith, Joseph, 3, 7, 14, 25, 31 castration, 55 Millennial Star, 61 Smoot Hearings, 31 children, death of, 3, 22, 43 Missouri, 7, 21 Snow, Eliza R., 57 Clark, Ezra T., 58 Mormon parallels, 33 Susquehanna County, crime and violence, 2, 3, 10 Native Americans, 9, 19 Pennsylvania, 35 16, 21, 29, 36, 37, 55 Nauvoo Mansion, 46 Tanner, Annie C., 58 D&C Section 27; 34 Nauvoo, 23, 39, 40, 45 Taylor, John, 40, Deseret Alphabet, 9, 61 New York, 10, 24 Temple, Nauvoo, 47 Forgeus, John A., 40 Nickerson, Freeman, 49 Temple, Salt Lake, 52 Gunnison, J.