Implementing Relationship Based Care in an Emergency Department Ruthie Waters Rogers Walden University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructions for Anesthesiology Programs Requesting the Addition of a Clinical Base Year (CBY) to an Existing 3-Year Accredited Residency

Instructions for Anesthesiology Programs Requesting the Addition of a Clinical Base Year (CBY) to an Existing 3-year Accredited Residency MATERIALS TO BE SUBMITTED: Attachment A: Clinical Base Year Information Form Attachment B: Provide specific goals and objectives (competency-based terminology) for each block rotation and indicate assessment tools that will be utilized. Attachment C: Include a description of both clinical and didactic experiences that will be provided (lectures, conferences, grand rounds, journal clubs). Attachment D: Provide an explanation of how residents will evaluate these experiences as well as supervising faculty members. Attachment E: Provide a one-page CV for the key supervising faculty. Attachment F: Clarify the role of the resident during each of the program components listed. Information about Anesthesiology Clinical Base Year ACGME RRC Program Requirements 7/08 1) Definition of Clinical Base Year (CBY) a) 12 months of ‘broad education in medical disciplines relevant to the practice of anesthesiology’ b) capability to provide the Clinical Base Year within the same institution is desirable but not required for accreditation. 2) Timing of CBY a) usually precedes training in clinical anesthesia b) strongly recommended that the CBY be completed before the resident begins the CA-2 year c) must be completed before the resident begins the CA-3 year 3) Routes of entry into Anesthesiology program a) Categorical program - Resident matches into categorical program (includes CB year, approved by RRC as part of the accredited -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

THE BUSINESS of EMERGENCY MEDICINE … MADE EASY! Sponsored by AAEM Services, the Management Education Division of AAEM

THE BUSINESS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE … MADE EASY! Sponsored by AAEM Services, the management education division of AAEM UDisclaimer The views presented in this course and syllabus represent those of the lecturers. The information is presented in a generalized manner and may not be applicable to your specific situation. Also, in many cases, one method of tackling a problem is demonstrated when many others (perhaps better alternatives for your situation) exist. Thus, it is important to consult your attorney, accountant or practice management service before implementing the concepts relayed in this course. UGoal This course is designed to introduce emergency physicians with no formal business education to running the business of emergency medicine. The title “The Business of Emergency Medicine Made Easy” is not meant to be demeaning. Instead, the course will convince anyone with the aptitude to become an emergency physician that, by comparison, running the business of emergency medicine is relatively simple. With off- the-shelf software and a little help from key business associates, we can run an emergency medicine business and create a win-win-win situation for the hospital, patients, and EPs. By eliminating an unnecessary profit stream as exists with CMGs, we can attract and retain better, brighter EPs. AAEM’s Certificate of Compliance on “Fairness in the Workplace” defines the boundaries within which independent groups should practice in order to be considered truly fair. Attesting to the following eight principles allows a group the privilege -

Emergency Medicine Medical Student Survival Guide

Emergency Medicine Medical Student Survival Guide Emergency Medicine: The Specialty Brian J Zink, MD, FACEP Professor and Chair Department of Emergency Medicine Alpert Medical School. Brown University 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Emergency Medicine: The Specialty Brian J. Zink, MD – Page 3 Chapter 2: Career Paths in Emergency Medicine Joseph Turner, MD, FACEP – Page 7 Chapter 3: Mentoring in Emergency Medicine Gloria J. Kuhn, DO, PhD, FACEP – Page 12 2 In 1961 the Alexandria Hospital emergency room (ER) in Alexandria, Virginia was reeling from a nearly 300% increase in patient visits in the past decade — up to 18,000 per year. Complaints and wait times were rising. Staffing the ER was a big problem as consigned medical staff objected to working in the ER, and the numbers of house staff had declined by 50%. A plan to use Georgetown University medical students to cover the night shifts had also failed.1 The specialty is no longer an afterthought in U.S. health care, but is viewed as a central component of care. Into this mix came James Mills, Jr., who had just been made president-elect of the Alexandria Hospital medical staff. Mills, a well-regarded local general practitioner, had worked shifts in the ER, and he liked the pace and variety of cases and was committed to helping the poor and underserved in his community. Mills was also finding his general practice less than satisfying. His idea for solving the problem in the Alexandria Hospital ER was very direct. He put together a plan to contract with the hospital for emergency department (ED) services with himself and three other physicians. -

The Incredible Breadth of Emergency Medicine Michael Blaivas*

edicine: O M p y e c n n A e c g c r e e s s m Blaivas, Emergency Med 2014, 4:2 E Emergency Medicine: Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2165-7548.1000181 ISSN: 2165-7548 Letter to the Editor Open Access The Incredible Breadth of Emergency Medicine Michael Blaivas* Professor of Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, St Francis Hospital, Columbus Georgia, USA *Corresponding author: Michael Blaivas, Professor of Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, St Francis Hospital, Columbus Georgia, USA, Tel: 706-414-5496; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: February 26, 2014, Acc date: March 04, 2014, Pub date: March 06, 2014 Citation: Blavias M (2014) The Incredible Breadth of Emergency Medicine. Emergency Med 4:181. doi: 10.4172/2165-7548.1000181 Copyright: © 2014 Blaivas M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Letter To the Editor presents to emergency physicians who are responsible to know pathophysiology and multiple treatment options [1]. One of the most challenging and amazing aspects of emergency medicine is the shear breadth of potential pathology and topics that In summary, emergency medicine is an incredible look at the front emergency medicine physicians may encounter on any particular shift lines of medical care that has no boundaries in organ system or disease and throughout their careers. This same factor attracts some medical pattern. -

A New Subspecialty Within Emergency Medicine

Emergency Cardiac Care – a new subspecialty within Emergency Medicine Prof V. Anantharaman Department of Emergency Medicine Singapore General Hospital Objectives • Heart disease is a common event and of concern to EM • Why have ECC as a defined sub-division • Types of cardiovascular issues relevant to EM • Fellowship • International networks Causes of Mortality – Singapore 2004 • Cancer 27.1% • Ischaemic Heart Disease 18.8% • Pneumonia 14.1% • Cerbrovascular Disease 9.8% • Accidents, Poisoning, Violence 6.5% • Other Heart Diseases 4.2% •COPD 3.1% Source: Singapore Health Facts, 2005 produced by Ministry of Health, Singapore Cardiac Arrest Statistics • # of AMI per annum 2,400 • # of OHCA per annum 1,000 • Survival rates (2004) 2.7% • # of IHCA per annum 2,600 • In-hospital survival rate 30.0% Cardiovascular Emergencies -- types • Acute Coronary Syndromes – Out-of-hospital – In-hospital – Chest Pain patients • Arrhythmias • Heart Failures • Cardiac Arrests • Thrombosis / Embolism • Hypertensive Emergencies • Cerebrovascular Emergencies Development of Cardiology • Invasive Cardiology • Nuclear Cardiology • Electro-physiology • Inpatient cardiology • Elective cardiology Where do cardiac emergencies occur? • Out – of – hospital – Residences – Public Places – GP clinics – Ambulances • Emergency Department • General non-cardiology wards Issues in Cardiac Emergencies • Morbidity – Slow recognition and unnecessary delay in emergency care results in poor functional cardiovascular status • Too many in the hospital staying too long – Expensive and -

Emergency Medicine Terminology in the United Kingdom—Time to Follow the Trend?

Emerg Med J 2001;18:79–80 79 REVIEWS Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.18.2.79 on 1 March 2001. Downloaded from Emergency medicine terminology in the United Kingdom—time to follow the trend? C Reid, L Chan Abstract medicine, accident and emergency de- Objective—To determine the frequency of partment and accident and emergency use of the terms “accident and emer- doctor, although the latter group still con- gency” and “emergency medicine” and stitutes the majority. their derivatives in original articles in the Conclusion—The use of emergency medi- Journal of Accident and Emergency Medi- cine to describe the specialty in the United cine. Kingdom is increasing, although this may Methods—Hand search of all articles in reflect the Journal’s growing international the Journal of Accident and Emergency standing. This trend should be taken into Medicine from September 1995 to July account in the debate over the specialty’s 2000, categorising the first use of termi- name in this country. Queen Alexandra nology in each original article to describe (Emerg Med J 2001;18:79–80) Hospital, Portsmouth the specialty, its departments, or their Keywords: terminology Correspondence to: staV into either accident and emergency Dr Reid, 36 Berkeley Close, or emergency medicine groups. Southampton SO15 2TR, Results—There is a clear trend towards UK As the debate on whether to change the name ([email protected]) increasing use of the terms emergency of our specialty in the United Kingdom from medicine, emergency physician and accident and emergency -

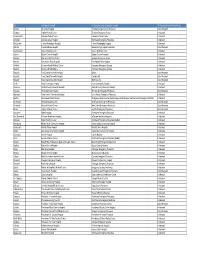

WA ER Physicians Group Directory Listing.Xlsx

City In-Network Hospital ER Physician group serving the hospital ER Physician Group Network Status Tacoma Allenmore Hospital Tacoma Emergency Care Physicians Out of Network Olympia Capital Medical Center Thurston Emergency Group In-Network Leavenworth Cascade Medical Center Cascade Medical Center In-Network Arlington Cascade Valley Hospital Northwest Emergency Physicians In-Network Wenatchee Central Washington Hospital Central Washington Hospital In-Network Ephrata Columbia Basin Hospital Beezley Springs Inpatient Services Out of Network Grand Coulee Coulee Medical Center Coulee Medical Center In-Network Dayton Dayton General Hospital Dayton General Hospital In-Network Spokane Deaconess Medical Center Spokane Emergency Group In-Network Ritzville East Adams Rural Hospital East Adams Rural Hospital In-Network Kirkland EvergreenHealth Medical Center Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Monroe EvergreenHealth Monroe Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Barton Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital CompHealth Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Staff Care Inc. Out of Network Forks Forks Community Hospital Forks Community Hospital In-Network Pomeroy Garfield County Memorial Hospital Garfield County Memorial Hospital In-Network Puyallup Good Samaritan Hospital Mt. Rainier Emergency Physicians Out of Network Aberdeen Grays Harbor Community Hospital Grays Harbor Emergency Physicians In-Network Seattle Harborview Medical Center Emergency Department at Harborview and -

Roadmap to Choosing a Medical Specialty Questions to Consider

Roadmap to Choosing a Medical Specialty Questions to Consider Question Explanation Examples What are your areas of What organ system or group of diseases do you Pharmacology & Physiology à Anesthesia scientific/clinical interest? find most exciting? Which clinical questions do Anatomy à Surgical Specialty, Radiology you find most intriguing? Neuroscience à Neurology, Neurosurgery Do you prefer a surgical, Do you prefer a specialty that is more Surgical à Orthopedics, Plastics, Neurosurgery medical, or a mixed procedure-oriented or one that emphasizes Mixed à ENT, Ob/Gyn, EMed, Anesthesia specialty? patient relationships and clinical reasoning? Medical à Internal Medicine, Neurology, Psychiatry See more on the academic advising website. What types of activities do Choose a specialty that will allow you to pursue Your activity options will be determined by your practice you want to engage in? your non-medical interests, like research, setting & the time constraints of your specialty. Look at teaching or policy work. the activities physicians from each specialty engage in. How much patient contact Do you like talking to patients & forming Internal & Family Medicine mean long-term patient and continuity do you relationships with them? What type of physical relationships. Radiology & Pathology have basically no prefer? interaction do you want with your patients? patient contact. Anesthesiologists & EMed docs have brief and efficient patient interactions. What type of patient Look at the typical patient populations in each Oncologists have patients with life-threatening diseases. population would you like specialty you’re considering. What type of Pediatricians may deal with demanding parents as well as to work with? physician-patient relationship do you want? sick infants and children. -

Mhealth in Emergency Medicine Grab Your Smartphone to Get a Grip on App-Driven Clinical Decision Rules and Tools

mHealth in Emergency Medicine Grab your smartphone to get a grip on app-driven clinical decision rules and tools. AUTHOR With the proliferation of smartphones over the past several years, apps Nicholas Genes, MD, PhD now play a prominent role in many social and work contexts, including Associate Professor, Department of medicine. This is enough of a phenomenon to have inspired the abbreviation Emergency Medicine, Icahn School of “mHealth,” short for mobile health. The number of app-driven clinical Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY calculators, checklists, and risk scores in common use in the emergency department (ED) has significantly increased and shows no sign of slowing. EB Medicine is pleased to bring you mHealth in Emergency Thanks to this digital development and innovation, clinical decision support Medicine, a Special Report is now just a finger-tap away. developed in conjunction with our strategic partner MDCalc. As of 2016, there were approximately 20,000 apps in the “Medical” Look for the first edition of our category of Apple’s app store.1 There are at least 300 apps specifically jointly published Calculated targeted to emergency clinicians,2 and given the variety of patient Decisions supplement, which presentations, general-purpose apps and apps from other specialties likely follows this report. It features merit usage in the ED. “Nick’s Picks,” content from 7 select MDCalc calculators Dr. Despite the abundance of apps and their potential to improve patient care, Genes deems as most essential to emergency medicine. Starting the decision of which apps to choose and use is left largely to each clinician, now, Calculated Decisions will be with little guidance on best practices or potential risks. -

Emergency Medicine Residency Program at Brandon Regional Hospital Is Part of the HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education Network

Emergency Medicine RESIDENCY PROGRAM AT Brandon Regional Medical Center Welcome to the AboutEmergency HCA MedicineHealthcare Residency Program at Brandon Regional Hospital The Emergency Medicine Residency Program at Brandon Regional Hospital is part of the HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education network. HCA Healthcare is the nation’s leading provider of quality, patient-centered care. We are also the leader in graduate medical education, all brought together by a single mission: Above all else, we are committed to the care and improvement of human life. ACGME ID: 1101100204 Salary PGY1 PGY2 PGY3 $52,934 $54,506 $56,212 Thank you for your interest in the HCA Healthcare/ USF Morsani College of Medicine GME Programs- Brandon Regional Hospital; Emergency Medicine (EM) residency program. This three-year program is designed to provide residents the broad experience, knowledge and clinical skills to excel as an emergency medicine physician. With the combined resources of Brandon Regional Hospital and Blake Medical Center, we ofer a well-rounded emergency medicine training experience, with exposure to Trauma, Pediatrics and two very busy emergency departments. Not to mention that our residents obtain additional pediatric emergency medicine and pediatric trauma experience through our partnership with Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital (JHACH). Our Faculty consist of specialty trained EM physicians in Research, Ultrasound, Simulation, International Emergency Medicine, Administration, Palliative Care, Addiction Medicine, and EMS Medicine to contribute to a well-rounded curriculum in EM. We also are fortunate to be a program under the sponsorship of the HCA Healthcare/ USF Morsani College of Medicine GME Programs, giving us extensive resources available in the areas of scholarly activity and clinical excellence. -

The Rape of Emergency Medicine

The Rape of Emergency Medicine James Keaney, M.D. © 2004 by the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Table of Contents Prologue..............................................................................1 Chapter One: Steinerman................................................. 8 Chapter Two: The Contracts and Their Holders ....... 13 Chapter Three: Suits and Scrubs....................................25 Chapter Four: Origin of a Species..................................45 Chapter Five: Crips and Bloods......................................54 Chapter Six: The Anderson Syndrome .......................... 62 Chapter Seven: Caveat Emptor .......................................82 Chapter Eight: Cro-Magnon ......................................... 99 Chapter Nine: The Quiet Room.................................... 108 Chapter Ten: The Other Side of Midnight ................ 126 Chapter Eleven: A One Way Ticket to Palookaville . 142 Chapter Twelve: Utah ................................................... 154 Chapter Thirteen: Pinnacle, Inc. .................................167 Chapter Fourteen: The Missing Chapter .................... 187 Chapter Fifteen: Chart Wars ....................................... 188 Chapter Sixteen: Physicians of a Lesser God ............. 200 Chapter Seventeen: Mea Culpa..................................... 214 Chapter Eighteen: California Dreamin’......................220 Chapter Nineteen: The Empire Strikes Back...............237 Chapter Twenty: The One Hundred and Eighty Thousand Dollar Pair of Sunglasses ...........................246