Vanbrugh, Blenheim Palace, and the Meanings of Baroque Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YORKSHIRE & Durham

MotivAte, eDUCAte AnD reWArD YORKSHIRE & Durham re yoUr GUests up for a challenge? this itinerary loCAtion & ACCess will put them to the test as they tear around a The main gateway to the North East is York. championship race track, hurtle down adrenaline- A X By road pumping white water and forage for survival on the north From London to York: york Moors. Approx. 3.5 hrs north/200 miles. it’s also packed with history. UnesCo World heritage sites at j By air Durham and hadrian’s Wall rub shoulders with magnifi cent Nearest international airport: stately homes like Castle howard, while medieval york is Manchester airport. Alternative airports: crammed with museums allowing your guests to unravel Leeds-Bradford, Liverpool, Newcastle airports 2,000 years of past civilisations. o By train And after all this excitement, with two glorious national parks From London-Kings Cross to York: 2 hrs. on the doorstep, there’s plenty of places to unwind and indulge while drinking in the beautiful surroundings. York Yorkshire’s National Parks Durham & Hadrian’s Wall History lives in every corner of this glorious city. Home to two outstanding National Parks, Yorkshire Set on a steep wooded promontory, around is a popular destination for lovers of the great which the River Wear curves, the medieval city of A popular destination ever since the Romans came outdoors. Durham dates back to 995 when it was chosen as to stay, it is still encircled by its medieval walls, the resting place for the remains of St Cuthbert, perfect for a leisurely stroll. -

A Unique Experience with Albion Journeys

2020 Departures 2020 Departures A unique experience with Albion Journeys The Tudors & Stuarts in London Fenton House 4 to 11 May, 2020 - 8 Day Itinerary Sutton House $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy Eastbury Manor House The Charterhouse St Paul’s Cathedral London’s skyline today is characterised by modern high-rise Covent Garden Tower of London Banqueting House Westminster Abbey The Globe Theatre towers, but look hard and you can still see traces of its early Chelsea Physic Garden Syon Park history. The Tudor and Stuart monarchs collectively ruled Britain for over 200 years and this time was highly influential Ham House on the city’s architecture. We discover Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of the city’s churches after the Great Fire of London along with visiting magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral. We also travel to the capital’s outskirts to find impressive Tudor houses waiting to be rediscovered. Kent Castles & Coasts 5 to 13 May, 2020 - 9 Day Itinerary $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy The romantic county of Kent offers a multitude of historic Windsor Castle LONDON Leeds Castle Margate treasures, from enchanting castles and stately homes to Down House imaginative gardens and delightful coastal towns. On this Chartwell Sandwich captivating break we learn about Kent’s role in shaping Hever Castle Canterbury Ightham Mote Godinton House English history, and discover some of its famous residents Sissinghurst Castle Garden such as Ann Boleyn, Charles Dickens and Winston Churchill. In Bodiam Castle a county famed for its castles, we also explore historic Hever and impressive Leeds Castle. -

An Exceptional Country House Set in 1 Acre of Walled Garden in the Prestigious Claremont Estate

AN EXCEPTIONAL COUNTRY HOUSE SET IN 1 ACRE OF WALLED GARDEN IN THE PRESTIGI OUS CLAREMONT ESTATE BLUE JAY, CLAREMONT DRIVE, ESHER, SURREY, KT10 9LU Furnished / Part Furnished £22,000 pcm + £285 inc VAT tenancy paperwork fee and other charges apply.* Available from 01/06/2018 £22,000 pcm Furnished / Part Furnished • 6 Bedrooms • 7 Bathrooms • 5 Receptions • Exceptional opportunity • Impressive from start to finish • Significant estate • Privacy is key • Ultra- modern living space • Indoor swimming pool including sauna & gym • Cinema room • Excellent proximity to schools including ACS & Claremont • EPC Rating C • Council Tax H Description An exceptional opportunity to rent a Property that is understated in style, flexible in use and above all, a home. Every aspect of security and technology has been carefully considered to provide hassle-free liveability. With a combination of intimacy and carefully designed entertainment and relaxation space, the five-bedroom property is entirely unique and has been designed for entertaining and to reinvent country house living. Blue Jay is accessed via a 100 metre long private tree-lined driveway. Security and alarm systems have been installed with external CCTV and flood lighting. The 3 metre high, 17th-century walls were designed by architect Sir John Vanbrugh, who built Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire and Castle Howard in North Yorkshire, two of the most significant historical country houses in England. Just 19 miles from Central London, Blue Jay is set within an acre of walled gardens, land that was formally part of Claremont House Gardens, a Royal residence designed by Sir John Vanbrugh and occupied by King George III and Queen Victoria in the late nineteenth century. -

Greenwich Park

GREENWICH PARK CONSERVATION PLAN 2019-2029 GPR_DO_17.0 ‘Greenwich is unique - a place of pilgrimage, as increasing numbers of visitors obviously demonstrate, a place for inspiration, imagination and sheer pleasure. Majestic buildings, park, views, unseen meridian and a wealth of history form a unified whole of international importance. The maintenance and management of this great place requires sensitivity and constant care.’ ROYAL PARKS REVIEW OF GREEWNICH PARK 1995 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD Greenwich Park is England’s oldest enclosed public park, a Grade1 listed landscape that forms two thirds of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. The parks essential character is created by its dramatic topography juxtaposed with its grand formal landscape design. Its sense of place draws on the magnificent views of sky and river, the modern docklands panorama, the City of London and the remarkable Baroque architectural ensemble which surrounds the park and its established associations with time and space. Still in its 1433 boundaries, with an ancient deer herd and a wealth of natural and historic features Greenwich Park attracts 4.7 million visitors a year which is estimated to rise to 6 million by 2030. We recognise that its capacity as an internationally significant heritage site and a treasured local space is under threat from overuse, tree diseases and a range of infrastructural problems. I am delighted to introduce this Greenwich Park Conservation Plan, developed as part of the Greenwich Park Revealed Project. The plan has been written in a new format which we hope will reflect the importance that we place on creating robust and thoughtful plans. -

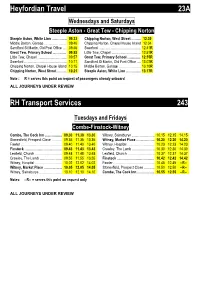

Timetables for Bus Services Under Review

Heyfordian Travel 23A Wednesdays and Saturdays Steeple Aston - Great Tew - Chipping Norton Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 09.33 Chipping Norton, West Street ……… 12.30 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 09.40 Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 12.34 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 09.46 Swerford ………………………………… 12.41R Great Tew, Primary School ………… 09.53 Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 12.51R Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 09.57 Great Tew, Primary School ………… 12.55R Swerford ………………………………… 10.11 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 13.02R Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 10.15 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 13.10R Chipping Norton, West Street ……... 10.21 Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 13.17R Note : R = serves this point on request of passengers already onboard ALL JOURNEYS UNDER REVIEW RH Transport Services 243 Tuesdays and Fridays Combe-Finstock-Witney Combe, The Cock Inn ………........ 09.30 11.30 13.30 Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.15 12.15 14.15 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 09.35 11.35 13.35 Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.20 12.20 14.20 Fawler ……………………………….. 09.40 11.40 13.40 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.23 12.23 14.23 Finstock ……………………………. 09.43 11.43 13.43 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 10.30 12.30 14.30 Leafield, Church ………………........ 09.48 11.48 13.48 Leafield, Church ………………........ 10.37 12.37 14.37 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 09.55 11.55 13.55 Finstock ……………………………. 10.42 12.42 14.42 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.02 12.02 14.02 Fawler ……………………………….. 10.45 12.45 --R-- Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.05 12.05 14.05 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 10.50 12.50 --R-- Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.10 12.10 14.10 Combe, The Cock Inn ………....... -

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ a Spacious and Exceptional Quality Conversion to Create Wonderful Living Space

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ A spacious and exceptional quality conversion to create wonderful living space Oxford City Centre 6 miles, Oxford Parkway 4 miles (London, Marylebone from 56 minutes), Hanborough Station 3 miles (London, Paddington from 66 minutes), Woodstock 4.5 miles, Witney 7 miles, M40 9/12 miles. (Distances & times approximate) n Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, large study kitchen/dining room, cloakroom, utility room, boiler room, master bedroom with en suite shower room, further 3 bedrooms and family bathroom n Double garage, attractive south facing garden n In all about 0.5 acres Directions Leave Oxford on the A44 northwards, towards Woodstock. At the roundabout by The Turnpike public house, turn left signposted Yarnton. Continue through the village towards Cassington and then, on entering Worton, turn right at the sign to Jericho Farm Barns, and the entrance to Tithe Barn will be will be seen on the right after a short distance. Situation Worton is a small hamlet situated just to the east of Cassington with easy access to the A40. Within Worton is an organic farm shop and cafe that is open at weekends. Cassington has two public houses, a newsagent, garden centre, village hall and primary school. Eynsham and Woodstock offer secondary schooling, shops and other amenities. The nearby historic town of Woodstock provides a good range of shops, banks and restaurants, as well as offering the World Heritage landscaped parkland of Blenheim Palace for relaxation and walking. There are three further bedrooms, family bathroom, deep eaves storage and a box room. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): an Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2003 The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Terrance Gerard Galvin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, European History Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Galvin, Terrance Gerard, "The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment" (2003). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 996. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Abstract In examining select works of English architects Joseph Michael Gandy and Sir John Soane, this dissertation is intended to bring to light several important parallels between architectural theory and freemasonry during the late Enlightenment. Both architects developed architectural theories regarding the universal origins of architecture in an attempt to establish order as well as transcend the emerging historicism of the early nineteenth century. There are strong parallels between Soane's use of architectural narrative and his discussion of architectural 'model' in relation to Gandy's understanding of 'trans-historical' architecture. The primary textual sources discussed in this thesis include Soane's Lectures on Architecture, delivered at the Royal Academy from 1809 to 1836, and Gandy's unpublished treatise entitled the Art, Philosophy, and Science of Architecture, circa 1826. -

Genealogical Sketch of the Descendants of Samuel Spencer Of

C)\\vA CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 096 785 351 Cornell University Library The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785351 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY : GENEALOGICAL SKETCH OF THE DESCENDANTS OF Samuel Spencer OF PENNSYLVANIA BY HOWARD M. JENKINS AUTHOR OF " HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS RELATING TO GWYNEDD," VOLUME ONE, "MEMORIAL HISTORY OF PHILADELPHIA," ETC., ETC. |)l)Uabei|it)ia FERRIS & LEACH 29 North Seventh Street 1904 . CONTENTS. Page I. Samuel Spencer, Immigrant, I 11. John Spencer, of Bucks County, II III. Samuel Spencer's Wife : The Whittons, H IV. Samuel Spencer, 2nd, 22 V. William. Spencer, of Bucks, 36 VI. The Spencer Genealogy 1 First and Second Generations, 2. Third Generation, J. Fourth Generation, 79 ^. Fifth Generation, 114. J. Sixth Generation, 175 6. Seventh Generation, . 225 VII. Supplementary .... 233 ' ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS. Page 32, third line, "adjourned" should be, of course, "adjoined." Page 33, footnote, the date 1877 should read 1787. " " Page 37, twelfth line from bottom, Three Tons should be "Three Tuns. ' Page 61, Hannah (Shoemaker) Shoemaker, Owen's second wife, must have been a grand-niece, not cousin, of Gaynor and Eliza. Thus : Joseph Lukens and Elizabeth Spencer. Hannah, m. Shoemaker. Gaynor Eliza Other children. I Charles Shoemaker Hannah, m. Owen S. Page 62, the name Horsham is divided at end of line as if pronounced Hor-sham ; the pronunciation is Hors-ham. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

VOL. XXXIII NO. 2 APRIL 1989 liTJ(JTAS RRmrrns UEDU51BS - NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS SAH NOTICES the National Council on Public History Special Announcement in cooperation with the Society for 1990 Annual Meeting-Boston, Industrial Archeology, June 23 -30, 1989, Massachusetts (March 28-April 1 ). At the Annual Meeting in Montreal this month, the SAH will Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois. Elisabeth Blair MacDougall, Harvard Industrial history has become an in University (retired), will be general chair kick off its 50th Anniversary Fund Raising Campaign. The Board of creasingly important concern for cultural of the meeting. Keith Morgan, Boston resource professionals. Thirty-eight na University, will serve as local chairman. Directors has approved as a con cept and slogan for this campaign, tional parks and numerous state facilities Headquarters for the meeting will be the are already involved in interpreting tech Park Plaza Hotel. A Call for Papers for "$50 FOR THE 50th." It is our goal that every member (Active catego nological and industrial history to the the Boston meeting appears as a four public. In the wake of Lowell National page insert in this issue. Those who wish ry and higher) contribute at least $50 to one of the campaign pro Historical Park, industrial heritage initia to submit papers for the Boston meeting tives all across the country are being are urged to do so promptly, and in any grams to be announced at the Annual Meeting in Montreal. All linked to economic development and case before the deadline of August 31, tourism projects. The assessment, inter 1989. -

Ebook Download Blenheim and the Churchill Family

BLENHEIM AND THE CHURCHILL FAMILY : A PERSONAL PORTRAIT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Henrietta Spencer-Churchill | 224 pages | 13 Jun 2013 | Ryland, Peters & Small Ltd | 9781782490593 | English | London, United Kingdom Blenheim and the Churchill Family : A Personal Portrait PDF Book Your Email Address. After his divorce the Duke married again a former friend of Consuelo, Gladys Deacon, another American. Finally, in the early days of the building the Duke was frequently away on his military campaigns, and it was left to the Duchess to negotiate with Vanbrugh. Condition: Mint. About this Item: Cico Books, The palace is linked to the park by a miniature railway, the Blenheim Park Railway. Views Read View source View history. Condition: Very Good. The birthplace of such notables as Winston Churchill, Blenheim Palace also was occupied by Lady Henrietta's colorful and illustrious great-grandmother, Consuelo Vanderbilt, a close friend of Winterthur founder Henry Francis du Pont and his wife Ruth. The Peace Treaty of Utrecht was about to be signed, so all the elements in the painting represent the coming of peace. Blenheim was once again a place of wonder and prestige. About this Item: Hardback. Next Article. When the 9th Duke inherited in , the Spencer-Churchills were almost bankrupt. Theirs was a very complicated relationship. Randolph already had a strained relationship with his parents from his precipitate marriage to an American, Jennie Jerome. The park is open daily from 9 a. The latter was re-paved by Duchene in the early 20th century. This stunning, lavishly illustrated book gives a personal insight into Blenheim Palace written by one of the Spencer-Churchill family who grew up surrounded by its treasures and soaking up its stories and legends. -

Read the Report!

JOHN MOOREHERITAGE SERVICES AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AND RECORDING ACTION AT LAND ADJACENT TO FARWAYS, YARNTON ROAD, CASSINGTON, OXFORDSHIRE NGR SP 4553 1122 On behalf of Blenheim Palace APRIL 2015 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report REPORT FOR Blenhiem Palace Estate Office Woodstock Oxfordshire OX20 1PP PREPARED BY Andrej Čelovský, with contributions from David Gilbert, Linzi Harvey, Claire Ingrem, Frances Raymon, and Jane Timby EDITED BY David Gilbert APPROVED BY John Moore ILLUSTRATION BY Autumn Robson, Roy Entwistle, and Andrej Čelovský FIELDWORK 18th Febuery to 22nd May 2014 Paul Blockley, Andrej Čelovský, Gavin Davis, Simona Denis, Sam Pamment, and Tom Rose-Jones REPORT ISSUED 14th April 2015 ENQUIRES TO John Moore Heritage Services Hill View Woodperry Road Beckley Oxfordshire OX3 9UZ Tel/Fax 01865 358300 Email: [email protected] Site Code CAYR 13 JMHS Project No: 2938 Archive Location The archive is currently held at John Moore Heritage Services and will be deposited with Oxfordhsire County Museums Service with accession code 2013.147 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report CONTENTS Page Summary i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Site Location 1 1.2 Planning Background 1 1.3 Archaeological Background 1 2 AIMS OF THE INVESTIGATION 3 3 STRATEGY 3 3.1 Research Design 3 3.2 Methodology 3 4 RESULTS 6 4.1 Field Results 6 4.2 Bronze Age 7 4.3 Iron Age 20 4.4 Roman