Encoding Language on Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Graphic Complexity in Writing Systems Helena Miton, Hans

The evolution of graphic complexity in writing systems Helena Miton, Hans-Jörg Bibiko, Olivier Morin Table of Contents A. General summary ................................................................................................................. 3 B. First registration (2018-02-22) ........................................................................................... 4 B. 1. Rationale for the study – Background - Introduction ....................................................... 4 B.2. Materials and Sources ............................................................................................................... 6 B.2.1. Inclusion criteria at the level of [scripts]: .................................................................................... 6 B.2.2. Inclusion criteria at the level of characters ............................................................................... 6 B.3. Measures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 B.3.1. Complexity ............................................................................................................................................. 7 B.3.2. Other characteristics of scripts ...................................................................................................... 8 B.4. Hypotheses and Tests ................................................................................................................. 8 B.4.1. Relationship between scripts’ size and -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

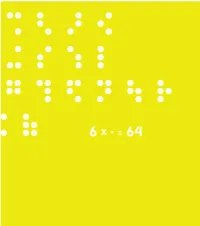

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

Foerdekreis 10 Jahre

( ) +# " , " , - ) . ! " # ' #$% & ' % ( * # !""# # ' . ( / ( 0 . & &"!' ! " .. % + # $ % &"!' . $) *)! )" 1 !!% ) * ()) * + !" #$ (' ' " + %& , $ )' ( !' ( & &"!' - * % % The IISE participants are projecting a preparatory school for visually impaired Isabel Torres children, here in Trivandrum. In this (Catalyst from Spain) school, children will learn Braille, Act Three sciences, mobility and living skills in a fun way. They will develop their confidence and creativity through sports, theatre, Three is the number of projects launched music and plastic arts. The team, who is by our first generation of IISE participants, already in touch with an architect, is raring in the context of the third act of our to design a cosy and sensory stimulating journey: “Getting real.” They presented environment for these children. their proposals to the general public and media on Saturday 25th of July, at the UST 2. Information is power. Together we are Global facility in Technopark, Trivandrum. stronger. These are not mere clichéd After calling -

Quantitative Linguistic Computing with Perl

Kelih, E. et al. (eds.), Issues in Quantitative Linguistics, Vol. 2, 117-128 Complexity of the Vai script revisited: A frequency study of the syllabary Andrij Rovenchak Charles Riley Tombekai Sherman 0. Introduction The present paper is a continuation of the quantitative studies of writing systems, in particular in the domain of African indigenous scripts. We analyze the statistical behavior of the script complexity defined accord- ing to the composition method suggested by Altmann (2004). The analysis of the Vai script complexity was made in a recent paper (Rovenchak , Mačutek, Riley 2009). To recall briefly, the idea of this approach is to decompose a letter into some simplest components (a point is given the weight 1, a straight line is given the weight 2, and an arc not exceeding 180 degrees has the weight of 3 units). The connections of such components are: a crossing (like in X) with weight 3, a crisp (like in T, V or L) with weight 2, and the continuous connection (like in O or S) with weight 1. For the Vai script, we also suggested that filled areas are given the weight of 2. With this method, a number of scripts had been analyzed: Latin (Altmann 2004), Cyrillic (Buk, Mačutek, Rovenchak 2008), several types of runes (Mačutek 2008), Nko (Rovenchak, Vydrin 2010). The uniformity hypothesis for the distribution of complexity was confirmed for all the scripts but the Vai syllabary. The failure in the latter case can be caused by the fact that syllabaries require some modification of this hypothesis as all the other scripts analyzed so far are alphabets. -

International Initiatives Committee Book Discussion

INTERNATIONAL INITIATIVES COMMITTEE BOOK DISCUSSION POSSIBILITIES Compiled by Krista Hartman, updated 12/2015 All titles in this list are available at the MVCC Utica Campus Library. Books already discussed: Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. (Nigeria ; Fiction) Badkken, Anna. Peace Meals: Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs and Other War Stories. Cohen, Michelle Corasanti. The Almond Tree. (Palestine/Israel/US ; Fiction) Hosseini, Khaled. A Thousand Splendid Suns. (Afghanistan ; Fiction) Lahiri, Jhumpa. The Namesake. (East Indian immigrants in US ; Fiction) Maathai, Wangari. Unbowed: a Memoir. (Kenya) Menzel, Peter & D’Alusio, Faith. Hungry Planet: What the World Eats. Barolini, Helen. Umbertina. (Italian American) Spring 2016 selection: Running for My Life by Lopez Lomong (Sudan) (see below) **************************************************************************************** Abdi, Hawa. Keeping Hope Alive: One Woman—90,000 Lives Changed. (Somalia) The moving memoir of one brave woman who, along with her daughters, has kept 90,000 of her fellow citizens safe, healthy, and educated for over 20 years in Somalia. Dr. Hawa Abdi, "the Mother Teresa of Somalia" and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, is the founder of a massive camp for internally displaced people located a few miles from war-torn Mogadishu, Somalia. Since 1991, when the Somali government collapsed, famine struck, and aid groups fled, she has dedicated herself to providing help for people whose lives have been shattered by violence and poverty. She turned her 1300 acres of farmland into a camp that has numbered up to 90,000 displaced people, ignoring the clan lines that have often served to divide the country. She inspired her daughters, Deqo and Amina, to become doctors. Together, they have saved tens of thousands of lives in her hospital, while providing an education to hundreds of displaced children. -

Chapter 6, Writing Systems and Punctuation

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Vai (Also Vei, Vy, Gallinas, Gallines) Is a Western Mande Langu

Distribution of complexities in the Vai script Andrij Rovenchak1, Lviv Ján Mačutek2, Bratislava Charles Riley3, New Haven, Connecticut Abstract. In the paper, we analyze the distribution of complexities in the Vai script, an indigenous syllabic writing system from Liberia. It is found that the uniformity hypothesis for complexities fails for this script. The models using Poisson distribution for the number of components and hyper-Poisson distribution for connections provide good fits in the case of the Vai script. Keywords: Vai script, syllabary, script analysis, complexity. 1. Introduction Our study concentrates mainly on the complexity of the Vai script. We use the composition method suggested by Altmann (2004). It has some drawbacks (e. g., as mentioned by Köhler 2008, letter components are not weighted by their lengths, hence a short straight line in the letter G contributes to the letter complexity by 2 points, the same score is attributed to each of four longer lines of the letter M), but they are overshadowed by several important advantages (it is applicable to all scripts, it can be done relatively easily without a special software). And, of course, there is no perfect method in empirical science. Some alternative methods are mentioned in Altmann (2008). Applying the Altmann’s composition method, a letter is decomposed into its components (points with complexity 1, straight lines with complexity 2, arches not exceeding 180 degrees with complexity 3, filled areas4 with complexity 2) and connections (continuous with complexity 1, crisp with complexity 2, crossing with complexity 3). Then, the letter complexity is the sum of its components and connections complexities. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

Free Downloads My Path Leads to Tibet: the Inspiring Story Of

Free Downloads My Path Leads To Tibet: The Inspiring Story Of HowOne Young Blind Woman Brought Hope To The Blind Children Of Tibet Defying everyoneÃÂs advice, armed only with her rudimentary knowledge of Chinese and Tibetan, Sabriye Tenberken set out to do something about the appalling condition of the Tibetan blind, who she learned had been abandoned by society and left to die. Traveling on horseback throughout the country, she sought them out, devised a Braille alphabet in Tibetan, equipped her charges with canes for the first time, and set up a school for the blind. Her efforts were crowned with such success that hundreds of young blind Tibetans, instilled with a newfound pride and an education, have now become self-supporting. A tale that will leave no reader unmoved, it demonstrates anew the power of the positive spirit to overcome the most daunting odds. Series: the inspiring story of how one young blind woman brought hope to the blind children of tibet Hardcover: 296 pages Publisher: Arcade Publishing; 1 edition (January 8, 2003) Language: English ISBN-10: 1559706589 ISBN-13: 978-1559706582 Product Dimensions: 5.9 x 1.1 x 8.5 inches Shipping Weight: 1.1 pounds (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.4 out of 5 stars 13 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #1,530,551 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #91 in Books > Travel > Asia > Tibet #559 in Books > Biographies & Memoirs > Ethnic & National > Chinese #1341 in Books > Biographies & Memoirs > Specific Groups > Special Needs When Tenberken, whose battle with retinal disease left her blind at age 13, was in her 20s, she studied Tibetan culture at the University of Bonn. -

Fonts & Encodings

Fonts & Encodings Yannis Haralambous To cite this version: Yannis Haralambous. Fonts & Encodings. O’Reilly, 2007, 978-0-596-10242-5. hal-02112942 HAL Id: hal-02112942 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02112942 Submitted on 27 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ,title.25934 Page iii Friday, September 7, 2007 10:44 AM Fonts & Encodings Yannis Haralambous Translated by P. Scott Horne Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo ,copyright.24847 Page iv Friday, September 7, 2007 10:32 AM Fonts & Encodings by Yannis Haralambous Copyright © 2007 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Printing History: September 2007: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Fonts & Encodings, the image of an axis deer, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. -

Foundation Stones “Foundation Stones” of the Library

Thompson Library Floor Inlays & Elevator Etchings Foundation Stones “Foundation Stones” of the Library Set in the terrazzo of the William • Abugidas have unit letters Guides to the Floor Inlays Oxley Thompson Memorial Library’s for simple syllables and diacritic ground and first floors are 49 metal marks to indicate different vowels or Ground Floor tablets documenting forms of writ- the absence of a vowel. Devanagari 1 Avestan - language of the Zoroastrian ten communication from around the (3), Tibetan (31), Thai (16), and Bur- holy books, NE Iran, ca. 7th c. BCE world. Forty-five additional etchings mese (#3, First floor elevator door) 2 Glagolitic - the oldest Slavic alphabet, are featured in the decorative framing ca. 9th c. CE show how these systems ramified as of the Stack Tower elevators. These they spread from India. 3 Letters of Devanagari - used for Sanskrit, examples include full writing systems Hindi and other Indic languages that have evolved over the past 4,000 4 Braille - devised in 1821 by Louis Braille to 5,000 years, some of their precur- • Syllabaries can be large, sors, and a few other graphic forms like Chinese (8), or small, like Japa- 5 Letters of the precursor of Ethiopic that collectively give a sense of the nese hiragana (9). The Linear B (32) syllabary (southern Arabia, early 1st millennium CE). immense visual range of inscriptive of pre-Homeric Greek was a sylla- techniques. Writing systems estab- bary. Mayan (44), the best-known of 6 Cherokee - the syllabary devised and publicly demonstrated by Sequuoyah lish the foundation upon which all the Meso-Americans scripts, was a in 1821 library collections are built, and it is syllabary, as are recently invented fitting that these “foundation stones” scripts for indigenous North American 7 Modern Korean - a headline font decorate this building.