Labour Tying Arrangements: an Enduring Aspect of Agrarian Capitalism in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

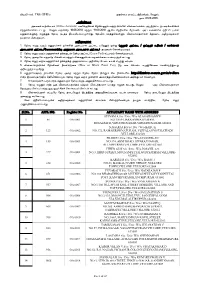

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

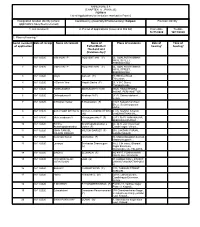

Chief Educational Office, Vellore Rte 25% Reservation - 2019-2020 Provisionaly Selected Students List

CHIEF EDUCATIONAL OFFICE, VELLORE RTE 25% RESERVATION - 2019-2020 PROVISIONALY SELECTED STUDENTS LIST Block School_Name Student_Name Register_No Student_Category Address Disadvantage MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 47 SMALL STREET KAVANUR VILLAGE Arakkonam Adlin S 5363109644 Group_Christian_Scheduled ARAKKONAM AND POST-631004-Vellore Dt Caste MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 46, SMALL STREET, KAVANOOR, Arakkonam Dhanu K 5346318086 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM - 631004-631004-Vellore Dt Disadvantage No. 190/3, School Street, MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Jency V 6409596936 Group_Hindu_Backward Kavanur Village & Post, ARAKKONAM Community Arakkonam-631004-Vellore Dt NO.24 , NAMMANERI VILLAGE, MOSUR MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Joseph J 5589617238 Weaker Section POST, ARAKKONAM TK, VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt Disadvantage 72 ADIDRAVIDAR COLONY ,BIG MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Leonajas E 3636068448 Group_Christian_Backward STREET,KAVANUR ,VELLORE-631004-Vellore ARAKKONAM Community Dt NO 150 3RD CROSS STREET MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Rohitha J 7715781823 Weaker Section PULIYAMANGALAM VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO.12, SILVERPET, EKHUNAGAR POST, Arakkonam Varun Kumar 8714376252 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM-631004-Vellore Dt NO 78/42 PERUMAL KOVIL STREET CHINNA MARY'S VISION MHSS, Disadvantage MOSUR COLONY MOSUR POST Arakkonam Yazhini R 7091288559 ARAKKONAM Group_Hindu_Scheduled Caste ARAKKONAM TALUK 631004-631004-Vellore Dt 27, METTU COLONY, ROYAL MATRIC HSS, Disadvantage Arakkonam Ashwathi R 6260258005 -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Katpadi Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 VISHALINI P POOVENTHAN (F) 66, SOALPURIYAMMAN KOVIL STREET, SHENBAKKAM, , 2 16/11/2020 VISHALINI P POOVENTHAN (F) 66, SOALPURIYAMMAN KOVIL STREET, SHENBAKKAM, , 3 16/11/2020 Divya Ganesh (H) 79, EB Koot Road , Thiruvalam, , 4 16/11/2020 H Samrin Yina Hayath Basha (F) 28, V O C Street, Tharapadavedu, , 5 16/11/2020 RAMKUMAR K INDHUMATHY N (W) 196/6, RAGAVENDRA NAGAR, PERIYAMITTOR, , 6 16/11/2020 Dhileepkumar K Krishnan N (F) 281/5, Chinna oddaneri, Vellore, , 7 16/11/2020 G Roshan Kumar S Gopinathan (F) 1/129, Kaliyamman Kovil Street, Seekarajapuram Mottur, , 8 16/11/2020 SANTHOSH SHYAM S NIRAJA LAKSHMI REKHA 9, KALAIGNAR NAGAR, (M) VANDRANTHANGAL, , 9 16/11/2020 Muthumadavan V Vinayagamurthy P (F) 6/273, BHEL ANNANAGAR, SEEKARAJAPURAM, , 10 16/11/2020 Srinithy Ananthapadmanaban s 20, 24 th east cross road Ananthapadmanaban Usha n (F) Gandhi nagar, Vellore, , 11 16/11/2020 JOHN SAMUEL WILSON DARLES (F) 558, LAKSHMI PURAM, WILSON DARLES GANDHINAGAR, , 12 16/11/2020 Gowtham Kumar Jaishankar (F) 36, Madandakuppam -

Notification for the Posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks Cycle – Iii/2020-2021 Tamilnadu Circle

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – III/2020-2021 TAMILNADU CIRCLE STC/12-GDSONLINE/2020 DATED 01.09.2020 Applications are invited by the respective engaging authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone/laptop supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device/laptop/equipment ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the Branch Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same Branch Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM and other Supervising authorities. -

(Unani) Practitioner List As on 31-08-2016

1 TAMIL NADU BOARD OF INDIAN MEDICINE ELECTION – 2016 (UNANI) PRACTITIONER LIST AS ON 31-08-2016 S.No Name & Address 2 1 Dr. SYED KHALEEFA THULLAH, B.U.M.S, 16327, N.No. 358, S/o. Syed Niamathulla Sahib 49, Bharathi Salai, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. 2 Dr. AZEEZUR RAHMANAZAMI, B.U.M.S, 24418 S/o. Moulana Mohamed Maman Sahib. No.2, Small Mosque Street, Poonamallee, Chennai - 600 056 3 Dr. HAKIM SYED IMAMUDDIN AHMED. B.U.M.S., 24450,N.No.262 S/o. Hakim Syed Muslihuddin Ahmed. A22, T.V.K.Street, M.M.D.A.Colony, Chennai - 600 106. 4 Dr. HAKEEM GIYASUDDIN AHMED, B.U.M.S., 24511,N.No.206 S/o. Muneeruddin Ahmed. Old No. 489, New No. 50, N.S.K. Nagar, Arumbakkam, Chennai - 600 106. 5 Dr. QUAZI ABUL HASANATH, Tabeeb-E-Kamil, 27279, N.No.267 S/o. Hakeem Masood Ahmed. No.97/A, Jamath Road, Noorullahpet, Vaniyambadi, Vellore District - 635 751. 6 Dr. SYED ABDUL MANNAN, Tabeeb-E-Kamil, 24513, N.No.187 S/o. Syed Abdur Rahaman. C-Type, No.3/142, SIDCO Nagar, Villivakkam, Chennai - 600 049. 7 Dr. SHAIK MADAR SAHIB, Tabib-I-Kamil, 24542, N.No.251 S/o. Shaik Kareem Sahib. Flat No.12, R.B.Paradise, No.26, Manickkam Street, Choolai Chennai-600 112. 8 Dr. ABDUL KHUDDUS AZAMI.Tabib-I-Kamil, 24563,N.No.369 S/o. S. Mohammad Abdul Aziz Azami No.90/14, P-Block, M.G.R 5th Street, M.M.D.A Colony,Arumbakkam,Chennai - 600106 9 Dr. -

The People of India

LIBRARY ANNFX 2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ^% Cornell University Library DS 421.R59 1915 The people of India 3 1924 024 114 773 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924024114773 THE PEOPLE OF INDIA =2!^.^ Z'^JiiS- ,SIH HERBERT ll(i 'E MISLEX, K= CoIoB a , ( THE PEOPLE OF INDIA w SIR HERBERT RISLEY, K.C.I.E., C.S.I. DIRECTOR OF ETHNOGRAPHY FOR INDIA, OFFICIER d'aCADEMIE, FRANCE, CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETIES OF ROME AND BERLIN, AND OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SECOND EDITION, EDITED BY W. CROOKE, B.A. LATE OF THE INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE "/« ^ood sooth, 7tiy masters, this is Ho door. Yet is it a little window, that looketh upon a great world" WITH 36 ILLUSTRATIONS AND AN ETHNOLOGICAL MAP OF INDIA UN31NDABL? Calcutta & Simla: THACKER, SPINK & CO. London: W, THACKER & CO., 2, Creed Lane, E.C. 191S PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES. e 7/ /a£ gw TO SIR WILLIAM TURNER, K.C.B. CHIEF AMONG ENGLISH CRANIOLOGISTS THIS SLIGHT SKETCH OF A LARGE SUBJECT IS WITH HIS PERMISSION RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION In an article on "Magic and Religion" published in the Quarterly Review of last July, Mr. Edward Clodd complains that certain observations of mine on the subject of " the impersonal stage of religion " are hidden away under the " prosaic title " of the Report on the Census of India, 1901. -

Student Details 2017 – 2019

St. Mary's College of Education, Katpadi Students Details - 2017 - 2019 Sl. Application Name of the Students Community Father's Name Mother's Name Address for Communication Mobile Number No Number 31/1 Kejaraj Mudhali Street, 1 12938002 Abirami L BC Loganathan R. K Senthamani Selvi L Darapadavedu, Katpadi, 9655863660 Vellore 632 007 5/281 St. Antoniyar Street 2 12938036 Alphonsaceline A BC Aruldoss S Antoniyammal MT Christianpet, TEL Post, Katpadi 9843567883 632 059 11/a 4 Jamedhar Thoppu, 3rd 3 12938070 Amarnath N SC Neethi Mohan P Stella Mary P. A Street, Pallikonda Vellore Dt. 9976667547 635 809 4/6 Madha Kovil Street, Kattipoondi Village, Kelur Post, 4 12938042 Amresh J SC Jayaraman A - 8760046477 Polur TK, T.V. Malai Dt. 606 907 St. Bridget Convent, Sipcot, 5 12938052 Anna Mary A OC Antha Raj B - 8220602104 Ranipet, Vellore Dt. 632 403 9 Upstairs 4th West Cross Road, West Gandhinagar, 6 12938050 Annapackiamary S BC Selva Raj S Roselin S 944276874 Gandhinagar Post Vellore 632006 Varaprastha International School, Mugulapalli, 7 12938039 Antonyirudayaraj R BC Rayappan S Anthonyammal Thummanapali Post, Hosur, 7986313980 Krishnagiri Dt. 635 105 77 Bisho David Nagar West, 8 12938020 Arokkiachithra M BC A. Martin Raja M. Margaret 7708088308 Vellore 632001 Brooksha Bad, SK Colony, Municipal QR, No. A/7 Port 9 12938033 Arokya Marry OC Mari Muthu M Pallamma 9531876473 Blair Chakkar Gaon Post, South Andaman 744 112 St, Joseph Convent Mission 10 12938019 Asha Kiran Kerketta OC Manuel Kerketta Assthi Kerketta Compound, Vallimalai Road 9476042261 Katpadi Stella Home, 5 Murugesan Nagar, 6th Cross Street, 11 12938081 Babyshalini M BC Madhalai Muthu Mary Christina 7339207638 thirunintravur, Thiruvallur, Chennai 602 024 102/B Chittur Main Road, 12 12938075 Bharathraja C BC Chinnappan S Sagaya Mary Katpadi, Katpadi TK, Vellore 9790724339 Dt. -

SENIOR BAILIFF-1.Pdf

SENIOR BAILIFF tpLtp vz;/6481-2018-V Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;w mYtyfk; ehs; /;? 14/07/2018 ntY}u; khtl;lk;. ntY}u; mwptpf;if tpLtp vz;/855-2018-V- ehs; 24/01/2018 ntY}u; khtl;lk;. Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpgjp mtu;fsJ mwptpf;ifapd;go ,t;tYtyfj;jpw;F tug;bgw;w tpz;zg;g';fspy;. fPH;fhqk; tpz;zg;g';fs; fyk; vz;/4?y; fz;;l fhuz';fSf;fhf epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ vd;W ,jd; K:yk; bjuptpf;fg;gLfpwJ/ khz;g[kpF brd;id cau;ePjpkd;wk; WP No.17676 of 2016 and W.M.P.15371 of 2016 ehs; 03/04/2017 ?y; tH';fpa tHpfhl;Ljy;fspd;go. tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F. mtu;fSila tpz;zg;g';fspy; fz;Ls;s FiwghLfs; eptu;j;jp bra;aj;jf;f tifapy; ,Ue;jhy;. mj;jifa FiwghLfis eptu;j;jp bra;a . rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F xU tha;g;g[ tH';fntz;Lk;/ mjd;go fPH;fhqk; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg;g';fspy; cs;s FiwghLfis. rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhd fhyk; 16/07/2018 Kjy; 18/07/2018 tiu vd epu;zapf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ/ tHpKiwfs; /;? (Instructions) 1) vd;d fhuz';fSf;fhf - FiwghLfSf;fhf tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;snjh. mjid eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhf rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; j';fs; milahs ml;il (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il) ,itfspy; VjhtJ xd;Wld;. -

The Story of Indenture Book Title

ANU Press Chapter Title: ‘Such a long journey’: The story of indenture Book Title: Levelling Wind Book Subtitle: Remembering Fiji Book Author(s): BRIJ V. LAL Published by: ANU Press. (2019) Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvr7fcdk.8 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ANU Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Levelling Wind This content downloaded from 223.190.124.245 on Thu, 16 Apr 2020 19:05:30 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 2 ‘Such a long journey’: The story of indenture1 But the past must live on, For it is the soul of today And the strength of the morn; A break to silent tears That mourn the dream of stillborn. — Churamanie Bissundayal2 Between 1834 and 1920, over 1 million Indian men and women were transported across the seas to serve as indentured labourers to sugar colonies around the world. -

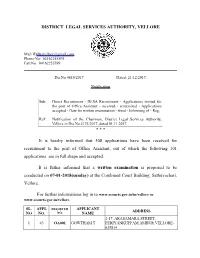

OA SELECTED-Vellore.Pdf

DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, VELLORE Mail [email protected] Phone No: 04162255599 Fax:No. 04162255599 Dis.No.4819/2017 Dated: 21/12/2017. Notification Sub: Direct Recruitment - DLSA Recruitment - Applications invited for the post of Office Assistant - received - scrutinized - Applications accepted - Date for written examination - fixed - Informing of - Reg. Ref: Notification of the Chairman, District Legal Services Authority, Vellore in Dis.No.4174/2017, dated 01.11.2017. * * * It is hereby informed that 508 applications have been received for recruitment to the post of Office Assistant, out of which the following 101 applications are in full shape and accepted. It is futher informed that a written examination is proposed to be conducted on 07-01-2018(sunday) at the Combined Court Building, Sathuvachari, Vellore. For further informations log in to www.ecourts.gov.in/tn/vellore or www.ecourts.gov.in/vellore. SL. APPL REGISTER APPLICANT ADDRESS NO NO. NO. NAME 1-17, ARASAMARA STREET, 1 43 OA001 GOWTHAM T PERIYANKUPPAM,AMBUR,VELLORE- 635814 24-56, ARASAMARA STREET, 2 44 OA002 BALAJI T K TIRUPATHUR,TIRUPATHUR,VELLORE- 635601 1-21, BIG MOSQUE STREET, 3 56 OA003 HUSSAIN A KASPA,VELLORE,VELLORE-632001 1-221, MEDONA STREET, VIRAPADIANPATTANAM AND 4 68 OA004 VIJAYA KUMAR S POST,THIRUCHENDUR,THOOTHUKKU DI-628216 69-61, BAJANAI MADAM BACKSIDE, MEENAKSHINAT KURUNTHERU, 5 127 OA005 HAN L KOTTAR,NAGERKOIL,KANNIYAKUMA RI-629002 18-55, PATEL STREET, 6 158 OA006 NATARAJAN S BHUVANESWARIPETTAI,GUDIYATHA M,VELLORE-632602 21, TIRUNAVUKKARASAR -

The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596

The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 1 The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 Edited by Dr. Anjan Saikia Cinnamara College Publication 2 The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 The Mirror Vol-III: A Bilingual Annual Journal of Department of History, Cinnamara College in collaboration with Assam State Archive, Guwahati, edited by Dr. Anjan Saikia, Principal, Cinnamara College, published by Cinnamara College Publication, Kavyakshetra, Cinnamara, Jorhat-8 (Assam). International Advisor Dr. Olivier Chiron Bordeaux III University, France Chief Advisor Dr. Arun Bandopadhyay Nurul Hassan Professor of History University of Calcutta, West Bengal Advisors Prof. Ananda Saikia Indrajit Kumar Barua Founder Principal President, Governing Body Cinnamara College Cinnamara College Dr. Om Prakash Dr. Girish Baruah School of Policy Sciences Ex-Professor, DKD College National Law University, Jodhpur Dergaon, Assam Dr. Daljit Singh Dr. Yogambar Singh Farswan Department of Punjab Historical Deparment of History & Archaeology Studies Punjabi University, Patiala H.N. Bahuguna Garhwal University Dr. Ramchandra Prasad Yadav Dr. Vasudev Badiger Associate Professor, Satyawati Professor, and Department of studies College University of Delhi in Ancient History & Archaeology Dr. Rupam Saikia, Director Kannada University, Karnataka College Development Council Dr. Rup Kumar Barman Dibrugarh University Professor, Department of History Dr. K. Mavali Rajan Jadavpur University, West Bengal Department of Ancient Indian Dr. Suresh Chand History Culture & Archeology Special Officer & Deputy Registrar copyrights Santiniketan Incharge-ISBN Agency Dr. Rahul Raj Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Ancient Indian Government of India, New Delhi History Culture & Archaeology Dr. Devendra Kumar Singh Banaras Hindu University Department of History Dr. Uma Shanker Singh Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Department of History Madhya Pradesh Dyal Singh College Dr.