Elementary Education Reform Committee Madras State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

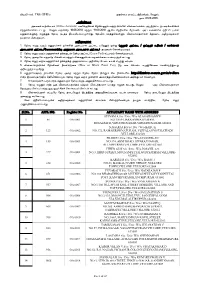

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

Chief Educational Office, Vellore Rte 25% Reservation - 2019-2020 Provisionaly Selected Students List

CHIEF EDUCATIONAL OFFICE, VELLORE RTE 25% RESERVATION - 2019-2020 PROVISIONALY SELECTED STUDENTS LIST Block School_Name Student_Name Register_No Student_Category Address Disadvantage MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 47 SMALL STREET KAVANUR VILLAGE Arakkonam Adlin S 5363109644 Group_Christian_Scheduled ARAKKONAM AND POST-631004-Vellore Dt Caste MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 46, SMALL STREET, KAVANOOR, Arakkonam Dhanu K 5346318086 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM - 631004-631004-Vellore Dt Disadvantage No. 190/3, School Street, MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Jency V 6409596936 Group_Hindu_Backward Kavanur Village & Post, ARAKKONAM Community Arakkonam-631004-Vellore Dt NO.24 , NAMMANERI VILLAGE, MOSUR MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Joseph J 5589617238 Weaker Section POST, ARAKKONAM TK, VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt Disadvantage 72 ADIDRAVIDAR COLONY ,BIG MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Leonajas E 3636068448 Group_Christian_Backward STREET,KAVANUR ,VELLORE-631004-Vellore ARAKKONAM Community Dt NO 150 3RD CROSS STREET MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Rohitha J 7715781823 Weaker Section PULIYAMANGALAM VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO.12, SILVERPET, EKHUNAGAR POST, Arakkonam Varun Kumar 8714376252 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM-631004-Vellore Dt NO 78/42 PERUMAL KOVIL STREET CHINNA MARY'S VISION MHSS, Disadvantage MOSUR COLONY MOSUR POST Arakkonam Yazhini R 7091288559 ARAKKONAM Group_Hindu_Scheduled Caste ARAKKONAM TALUK 631004-631004-Vellore Dt 27, METTU COLONY, ROYAL MATRIC HSS, Disadvantage Arakkonam Ashwathi R 6260258005 -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Katpadi Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 VISHALINI P POOVENTHAN (F) 66, SOALPURIYAMMAN KOVIL STREET, SHENBAKKAM, , 2 16/11/2020 VISHALINI P POOVENTHAN (F) 66, SOALPURIYAMMAN KOVIL STREET, SHENBAKKAM, , 3 16/11/2020 Divya Ganesh (H) 79, EB Koot Road , Thiruvalam, , 4 16/11/2020 H Samrin Yina Hayath Basha (F) 28, V O C Street, Tharapadavedu, , 5 16/11/2020 RAMKUMAR K INDHUMATHY N (W) 196/6, RAGAVENDRA NAGAR, PERIYAMITTOR, , 6 16/11/2020 Dhileepkumar K Krishnan N (F) 281/5, Chinna oddaneri, Vellore, , 7 16/11/2020 G Roshan Kumar S Gopinathan (F) 1/129, Kaliyamman Kovil Street, Seekarajapuram Mottur, , 8 16/11/2020 SANTHOSH SHYAM S NIRAJA LAKSHMI REKHA 9, KALAIGNAR NAGAR, (M) VANDRANTHANGAL, , 9 16/11/2020 Muthumadavan V Vinayagamurthy P (F) 6/273, BHEL ANNANAGAR, SEEKARAJAPURAM, , 10 16/11/2020 Srinithy Ananthapadmanaban s 20, 24 th east cross road Ananthapadmanaban Usha n (F) Gandhi nagar, Vellore, , 11 16/11/2020 JOHN SAMUEL WILSON DARLES (F) 558, LAKSHMI PURAM, WILSON DARLES GANDHINAGAR, , 12 16/11/2020 Gowtham Kumar Jaishankar (F) 36, Madandakuppam -

Student Details 2017 – 2019

St. Mary's College of Education, Katpadi Students Details - 2017 - 2019 Sl. Application Name of the Students Community Father's Name Mother's Name Address for Communication Mobile Number No Number 31/1 Kejaraj Mudhali Street, 1 12938002 Abirami L BC Loganathan R. K Senthamani Selvi L Darapadavedu, Katpadi, 9655863660 Vellore 632 007 5/281 St. Antoniyar Street 2 12938036 Alphonsaceline A BC Aruldoss S Antoniyammal MT Christianpet, TEL Post, Katpadi 9843567883 632 059 11/a 4 Jamedhar Thoppu, 3rd 3 12938070 Amarnath N SC Neethi Mohan P Stella Mary P. A Street, Pallikonda Vellore Dt. 9976667547 635 809 4/6 Madha Kovil Street, Kattipoondi Village, Kelur Post, 4 12938042 Amresh J SC Jayaraman A - 8760046477 Polur TK, T.V. Malai Dt. 606 907 St. Bridget Convent, Sipcot, 5 12938052 Anna Mary A OC Antha Raj B - 8220602104 Ranipet, Vellore Dt. 632 403 9 Upstairs 4th West Cross Road, West Gandhinagar, 6 12938050 Annapackiamary S BC Selva Raj S Roselin S 944276874 Gandhinagar Post Vellore 632006 Varaprastha International School, Mugulapalli, 7 12938039 Antonyirudayaraj R BC Rayappan S Anthonyammal Thummanapali Post, Hosur, 7986313980 Krishnagiri Dt. 635 105 77 Bisho David Nagar West, 8 12938020 Arokkiachithra M BC A. Martin Raja M. Margaret 7708088308 Vellore 632001 Brooksha Bad, SK Colony, Municipal QR, No. A/7 Port 9 12938033 Arokya Marry OC Mari Muthu M Pallamma 9531876473 Blair Chakkar Gaon Post, South Andaman 744 112 St, Joseph Convent Mission 10 12938019 Asha Kiran Kerketta OC Manuel Kerketta Assthi Kerketta Compound, Vallimalai Road 9476042261 Katpadi Stella Home, 5 Murugesan Nagar, 6th Cross Street, 11 12938081 Babyshalini M BC Madhalai Muthu Mary Christina 7339207638 thirunintravur, Thiruvallur, Chennai 602 024 102/B Chittur Main Road, 12 12938075 Bharathraja C BC Chinnappan S Sagaya Mary Katpadi, Katpadi TK, Vellore 9790724339 Dt. -

SENIOR BAILIFF-1.Pdf

SENIOR BAILIFF tpLtp vz;/6481-2018-V Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;w mYtyfk; ehs; /;? 14/07/2018 ntY}u; khtl;lk;. ntY}u; mwptpf;if tpLtp vz;/855-2018-V- ehs; 24/01/2018 ntY}u; khtl;lk;. Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpgjp mtu;fsJ mwptpf;ifapd;go ,t;tYtyfj;jpw;F tug;bgw;w tpz;zg;g';fspy;. fPH;fhqk; tpz;zg;g';fs; fyk; vz;/4?y; fz;;l fhuz';fSf;fhf epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ vd;W ,jd; K:yk; bjuptpf;fg;gLfpwJ/ khz;g[kpF brd;id cau;ePjpkd;wk; WP No.17676 of 2016 and W.M.P.15371 of 2016 ehs; 03/04/2017 ?y; tH';fpa tHpfhl;Ljy;fspd;go. tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F. mtu;fSila tpz;zg;g';fspy; fz;Ls;s FiwghLfs; eptu;j;jp bra;aj;jf;f tifapy; ,Ue;jhy;. mj;jifa FiwghLfis eptu;j;jp bra;a . rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F xU tha;g;g[ tH';fntz;Lk;/ mjd;go fPH;fhqk; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg;g';fspy; cs;s FiwghLfis. rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhd fhyk; 16/07/2018 Kjy; 18/07/2018 tiu vd epu;zapf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ/ tHpKiwfs; /;? (Instructions) 1) vd;d fhuz';fSf;fhf - FiwghLfSf;fhf tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;snjh. mjid eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhf rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; j';fs; milahs ml;il (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il) ,itfspy; VjhtJ xd;Wld;. -

OA SELECTED-Vellore.Pdf

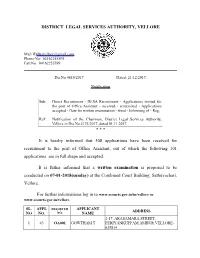

DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, VELLORE Mail [email protected] Phone No: 04162255599 Fax:No. 04162255599 Dis.No.4819/2017 Dated: 21/12/2017. Notification Sub: Direct Recruitment - DLSA Recruitment - Applications invited for the post of Office Assistant - received - scrutinized - Applications accepted - Date for written examination - fixed - Informing of - Reg. Ref: Notification of the Chairman, District Legal Services Authority, Vellore in Dis.No.4174/2017, dated 01.11.2017. * * * It is hereby informed that 508 applications have been received for recruitment to the post of Office Assistant, out of which the following 101 applications are in full shape and accepted. It is futher informed that a written examination is proposed to be conducted on 07-01-2018(sunday) at the Combined Court Building, Sathuvachari, Vellore. For further informations log in to www.ecourts.gov.in/tn/vellore or www.ecourts.gov.in/vellore. SL. APPL REGISTER APPLICANT ADDRESS NO NO. NO. NAME 1-17, ARASAMARA STREET, 1 43 OA001 GOWTHAM T PERIYANKUPPAM,AMBUR,VELLORE- 635814 24-56, ARASAMARA STREET, 2 44 OA002 BALAJI T K TIRUPATHUR,TIRUPATHUR,VELLORE- 635601 1-21, BIG MOSQUE STREET, 3 56 OA003 HUSSAIN A KASPA,VELLORE,VELLORE-632001 1-221, MEDONA STREET, VIRAPADIANPATTANAM AND 4 68 OA004 VIJAYA KUMAR S POST,THIRUCHENDUR,THOOTHUKKU DI-628216 69-61, BAJANAI MADAM BACKSIDE, MEENAKSHINAT KURUNTHERU, 5 127 OA005 HAN L KOTTAR,NAGERKOIL,KANNIYAKUMA RI-629002 18-55, PATEL STREET, 6 158 OA006 NATARAJAN S BHUVANESWARIPETTAI,GUDIYATHA M,VELLORE-632602 21, TIRUNAVUKKARASAR -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2019 [Price : Rs. 20.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 3A] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 16, 2019 Thai 2, Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2050 Part VI–Section 1 (Supplement) NOTIFICations BY HEADS OF departments, ETC. tamil NADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL, CHENNAI. Electoral Roll of Members of Nurses League of Christian Medical Association of India (South India Branch) registered as on date under Tamilnadu Nurses and Midwives Act III of 1926 under Section 11(2)(a) under Rule 7(2). (Ref.No.432/NC/2018) No. VI(1)/33/2019. Tnnc CMAI S.No. Nurse Name Qualification Address Number Number Principal Quarters, C.S.I Mission 1 21940 11395 B.VIJAYA RANI M.Sc.[N] Compound,Dharapuram, Tirupur, Alappuzha, Tamil Nadu, India - 638656 2A2 / Abc Block, Christian 2 24244 12692 SELVAKUMARI SEKARAN M.Sc.[N] Medical College.,Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India - 632 004 Office of the Nursing Superintendent, 3 24387 13215 P. FLORENCE SUJIA BAI M.Sc.[N] CMC,Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India- 632004 Mr.Stanley Jones , No-142, Anna Nagar, 4 102705 13227 EVANGELINE REBECCA .S DGNM Vallimalai Road, Katapdi, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India - 632007 Wilson Villa, 13/105 A, Pullierangi, Marthandam, Sree Ramakrishna College of Nursing, Padanilam, 5 24377 13386 Y. VILSONDAS PBB.Sc.[N] Kulasekharam, KK Dt. 629161, Thiruvattar, Kanniyakumari, India - 629177 [ 1 ] DTP—VI-1 A-Sup. (3A)—1 2 Tnnc CMAI S.No. Nurse Name Qualification Address Number Number School Of Nursing, Scudder Memorial Hospital, 6 28173 13993 M.J.ASHA MANOHARI PBB.Sc.[N] Ranipet.,Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India - 632401 No. -

MTF-Tamil Nadu-Members List

MOTHER TERESA CHARITABLE TRUST ‐ MTF‐MEMBERS LIST COIMBATORE ‐ 03 MOBILE TELEPHONE SL NO NAME EMAIL ID NUMBER NUMBER 3000 R. MUTHARASU 09486032208 09791500555 NO. 2/190, CHETTI THOTTAM, EDAYARPALAYAM ROAD, VADAVALLI, COIMBATORE‐641041 [email protected] 3001 K. DURAISWAMY 09442528637 NO. II/26, ESIC STAFF QUARTERS, KALEESHWARA NAGAR, KATTOOR, COIMBATORE 3002 PRESHA PREMKUMAR 9944473618 OMSAKTHY NAGAR, POLICE QUAETERS ROAD, GANAPATHY,COIMBATORE‐ ‐641 004 [email protected] 93/W.1, SOUTH STREET,POONAMALEE GUNDU POST, KAMATCHIPURAM 3003 DR.N.ROHINI VIA THENI ‐625520 CUDDALORE ‐ 04 3004 A. SELVAM 09443185886 25, K.T.R. MEGAR, BEACH ROAD, CUDDALORE‐1 3005 S. SHOBAN BABU 09865162382 04142‐239377 NO. 252, ANGALAMMAN KOVIL STREET, KARAIKADDU, CIPCOTE (PO), CUDDALORE‐607005 shobansubramani@yahooy 3006 D. MURALIDHARAN 09443182960 NO. 50, SENTHAMARAI NAGAR, NEAR ALPETTAI CHECK‐POST, CUDDALORE‐607001 [email protected] 3007 P. SWAMY MANIKANDAN 09585862847 OLD NO. 119/3, NEW NO. 3/119, MAIN ROAD, VEMBUR (PO), VIRUDHACHALAM, VELLORE 3008 B. SIVAKUMAR 09751874539 NO. 70, PERIYA NERKUNAM, CHINNANERKUNAM‐(PO),CHIDAMBARAM‐608704,CUDDALORE [email protected] 1ST FLOOR, JEEVA COMPLEX, OPP TO KALAINGAR PARK, CUDDALORE ROAD, 3009 J. SABANAYAKAM 09486934710 VADALUR‐607303 3010 S. VINNI 09789594437 NO. 16, BAGAVATHY AMMAN KOVIL STREET, VILVA NAGAR, CUDDALORE‐607001 3011 M. NALINI 09840492639 NO. 11, MEENATCHI NAGAR, NEAR K.V.K. THEATR, V.P.M. SALAI, GINGEE‐604202 [email protected] 45, MARIYAMMAN KOIL STREET, ERALIKUPPAM (VIL), VELIYANUR (PO), 3012 E. ARUMUGAM 09363204214 TINDIVANAM (TK), VILUPURAM‐604304 3013 S.S. VENKATESAN 044‐31115747 044‐24959159 NATTAR MANGALAM VILLAGEVILLAGE,, VALLAM POSTPOST,, GINJEE TALUKTALUK,, VILLUPURAM DHARMAPURI ‐ 05 3014 S. SURESH 09943754190 KATHIRIPATTI (PO), HARUR 9TK), DHARMAPURI‐636906 3015 M. -

District Legal Services Authority, Vellore

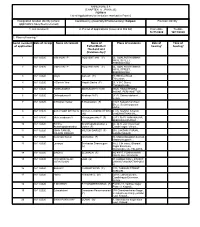

DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, VELLORE Mail [email protected] Phone No: 04162255599 Fax:No. 04162255599 Dis.No.4813 /2017 Dated: 21/12/2017. Notification Sub: Direct Recruitment - DLSA Recruitment - Applications invited for the post of Junior Administrative Assistant - received - scrutinized - Certain applications not in full shape - Rejected - Informing of - Reg. Ref: Notification of the Chairman, District Legal Services Authority, Vellore in Dis.No.4174/2017, dated 01.11.2017. * * * It is hereby informed that 2157 applications have been received for recruitment to the post of Junior Administrative Assistant, out of which the following 1346 applications are Rejected for the reason mentioned against the candidates in column no.5. SL. APPL APPLICANT ADDRESS REASON FOR REJECTION NO NO. NAME 135-187 ANNAMALAI STREET, 1 1 RISHIGANESH V MARAPPALAYAM, ERODE,,ERODE-638 SSLC MARK SHEET NOT ENCLOSED 001 6-80, PILLAIYAR KOIL STREET, L G PUDHUR, ENVELOPE WITH POSAL FEE NOT 2 3 BABU A KARASAMANGALAM,KATPADI,VELL ENCLOSED ORE-632 202 2-2-B, ADIDRAVIDAR COLONY, COVERING LETTER NOT ENCLOSED 3 5 SURESH S MATRAPALLI,TIRUPATTUR,VELLORE- SSLC MARKSHEET NOT ENCLOSED 635 652 ENVELOPE WITH POSAL FEE 234-127, MARIYAMMAN KOIL STREET, (RS.50/-) NOT ENCLOSED 4 6 PUGAZENTHI D KV KUPPAM,KATPADI,VELLORE-632 COVERING LETTER NOT ENCLOSED 201 HSC CERTIFICATE NOT ENCLOSED CERTIFICATES NOT SELF ATTESTED 42,VEDAMANICKAM NAGAR, 5 20 GANGA R KARAIPATTAI,,KANCHIPURAM-631 HSC CERTIFICATE NOT ENCLOSED 552 SL. APPL APPLICANT ADDRESS REASON FOR REJECTION NO NO. NAME -

![21F] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2015 Vaikasi 13, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2046](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6581/21f-chennai-wednesday-may-27-2015-vaikasi-13-manmadha-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2046-3656581.webp)

21F] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2015 Vaikasi 13, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2046

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price : Rs. 253.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 21F] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2015 Vaikasi 13, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2046 Part VI–Section 1 (Supplement) NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. TAMIL NADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL, CHENNAI. (Constituted under Tamil Nadu Act III of 1926) LIST OF NAMES OF REGISTERED NURSES AND MIDWIVES ELECTORAL ROLLS FOR THE YEAR 2003. DTP—VI-1 Sup. (21F)—1 [ 1 ] THE TAMILNADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL No-140,JeyaPrakash Narayanan Maligai,Santhome High Road, Mylapore,Chennai-600004. emailID:[email protected] Register Of Nurse Eletro Roll Reports in Fox-Pro 01/01/2003 To 31/12/2003 Basic Original GNM Cat./ Sec. S.No Reg.No & Date Canditate Name & Address Particulars Midwife No. & Dt. 1 CertificateID: Ms/Mrs SEEMA MANI B.Sc.,(Nursing) Part :A 18761 Date Of Birth:15/04/1980, TAMILNADU DR.MGR MEDICAL Section:I 02/01/2003 Address:-D/O.M.V.MANI,,MATHURAMCHERIL UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI RN NO :55344 (Female) HOUSE, P.OVADAVATHOOR,, SRI MOOKAMBIKA COLLEGE OF 02/01/2003 KOTTAYAM, KERALA,CHENNAI, NURSING, KULASHEKHARAM, RM No: 61420 0 KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT Community:-- Religon:-- From 11/NOV/1997 To 23/NOV/2001 NOV/2001 Mobile No :- EmailId :-- 2 CertificateID: Ms/Mrs RATHI R.K. B.Sc.,(Nursing) Part :A 18763 Date Of Birth:05/06/1980, TAMILNADU DR.MGR MEDICAL Section:I 02/01/2003 Address:-D/O.KANNIAPPAN .R,M.268, ANBU UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI RN NO :55345 (Female) NAGAR, MAHARAJAN NAGAR POST,, COLLEGE OF NURSING, SAVEETHA 02/01/2003 PALAYAMKOTTAI, TIRUNELVELI,CHENNAI, DENTAL COLLEGE & RM No: 61421 0 HOSPITALS,CHENNAI Community:-BC Religon:-Christian From 01/OCT/1997 To 21/NOV/2001 NOV/2001 Mobile No :- EmailId :-- 3 CertificateID: Ms/Mrs PADMA DEVI T. -

Tpltp Vz;/ 5685-2017-V Kjd;Ik Khtl;L Epjpkd;W Mytyfk; Nty}U; Khtl;Lk;

tpLtp vz;/ 5685-2017-V Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;w mYtyfk; ntY}u; khtl;lk;. ntY}u ehs; /;? 25/06/2017 mwptpf;if tpLtp vz;/3296-2017-V- ehs; 04/04/2017 ntY}u; khtl;lk;. Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpgjp mtu;fsJ mwptpf;ifapd;go ,t;tYtyfj;jpw;F tug;bgw;w tpz;zg;g';fspy;. fPH;fhqk; tpz;zg;g';fs; fyk; vz;/3?y; fz;;l fhuz';fSf;fhf epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ vd;W ,jd; K:yk; bjuptpf;fg;gLfpwJ/ khz;g[kpF brd;id cau;ePjpkd;wk; WP No.17676 of 2016 and W.M.P.15371 of 2016 ehs; 03/04/2017 ?y; tH';fpa tHpfhl;Ljy;fspd;go. tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F. mtu;fSila tpz;zg;g';fspy; fz;Ls;s FiwghLfs; eptu;j;jp bra;aj;jf;f tifapy; ,Ue;jhy;. mj;jifa FiwghLfis eptu;j;jp bra;a . rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fSf;F xU tha;g;g[ tH';fntz;Lk;/ mjd;go fPH;fhqk; epuhfupf;fg;gl;l tpz;zg';fspy; cs;s FiwghLfis. rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhd fhyk; 27/06/2017 Kjy; 29/06/2017 tiu vd epu;zapf;fg;gl;Ls;sJ/ tHpKiwfs; /;? (Instructions) 1) vd;d fhuz';fSf;fhf - FiwghLfSf;fhf tpz;zg;g';fs; epuhfupf;fg;gl;Ls;snjh. mjid eptu;j;jp bra;tjw;fhf rk;ge;jg;gl;l tpz;zg;gjhuu;fs; j';fs; milahs ml;il (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il) ,itfspy; VjhtJ xd;Wld;. -

Vellore Corporation -Street Details

Ward S.No. Street Name S.No No 1 WD-01 01 VANDRANTHANGAL MAIN ROAD 2 WD-01 02 KALPUDUR BAJANI KOIL STREET 3 WD-01 03 THIRUVANKADA MUDALI STREET 4 WD-01 04 THIRUVANKATAM MUDHALI LANE 5 WD-01 05 KALPUDUR PILLIYAR KOIL STREET 6 WD-01 06 KALPUDUR NEHRU STREET 7 WD-01 07 RAJALINGA NAGAR 8 WD-01 08 RAJIV GANDHI NAGAR 9 WD-01 09 AMMAN NAGAR 10 WD-01 10 SAKTHI NAGAR 11 WD-01 11 KANNUSAMY NAGAR 12 WD-01 12 KALPUDHUR L.F.ROAD 13 WD-01 13 L.F.Road East Kalpudur 14 WD-01 14 L.F.road West Kalpudur 15 WD-01 15 M.G.R.NAGAR 2nd WEST STREET 16 WD-01 16 M.G.R.NAGAR 3rd WEST STREET 17 WD-01 17 M.G.R.NAGAR 4th WEST STREET 18 WD-01 18 M.G.R.NAGAR 5th WEST STREET 19 WD-01 19 M.G.R.NAGAR 8th NORTH STREET 20 WD-01 20 M.G.R.NAGAR 9th NORTH STREET 21 WD-01 21 M.G.R.NAGAR 10th NORTH STREET 22 WD-01 22 CHENGUTTAI BHARATHIYAR STREET 23 WD-01 23 CHENGUTTAI NEHRU STREET 24 WD-01 24 CHENGUTTAI KULAKKARAI STREET 25 WD-01 25 MOUNAGURUSAMI STREET 26 WD-01 26 CHENGUTTAI JAYALALITHA NAGAR 27 WD-01 27 CHENGUTTAI SATHITAM STREET 28 WD-01 28 M.G.R.NAGAR 6th WEST STREET 29 WD-01 29 Chenguttai Indira Nagar 30 WD-01 30 CHATHIRAM STREET 31 WD-01 31 NEHRU STREET 32 WD-01 32 KAMARAJ NAGAR KALPUDHUR 33 WD-01 33 M.G.R.NAGAR 7th NORTH STREET 34 WD-02 01 Railway gate street 35 WD-02 02 Sangam street 36 WD-02 03 Mottai gaunder street 37 WD-02 04 Munisamy gaunder street 38 WD-02 05 Nattu vellai gaunder street 39 WD-02 06 Ariyapadi vellai gaunder street 40 WD-02 07 Pillaiyar koil street 41 WD-02 08 Kizhmottur road 1 42 WD-02 09 Kasam Kootu road 43 WD-02 10 Karigiri road 44 WD-02 11 Pooncholai