Success in Conserving the Bird Diversity in Tropical Forests Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

BIRDCONSERVATION the Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW a Life Shaped by Migration

BIRDCONSERVATION The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW A Life Shaped By Migration The years have rolled by, leaving me with many memories touched by migrating birds. Migrations tell the chronicle of my life, made more poignant by their steady lessening through the years. still remember my first glimmer haunting calls of the cranes and Will the historic development of of understanding of the bird swans together, just out of sight. improved relations between the Imigration phenomenon. I was U.S. and Cuba nonetheless result in nine or ten years old and had The years have rolled by, leaving me the loss of habitats so important to spotted a male Yellow Warbler in with many memories touched by species such as the Black-throated spring plumage. Although I had migrating birds. Tracking a Golden Blue Warbler (page 18)? And will passing familiarity with the year- Eagle with a radio on its back Congress strengthen or weaken the round and wintertime birds at through downtown Milwaukee. Migratory Bird Treaty Act (page home, this springtime beauty was Walking down the Cape May beach 27), America’s most important law new to me. I went to my father for each afternoon to watch the Least protecting migratory birds? an explanation of how I had missed Tern colony. The thrill of seeing this bird before. Dad explained bird “our” migrants leave Colombia to We must address each of these migration, a talk that lit a small pour back north. And, on a recent concerns and a thousand more, fire in me that has never been summer evening, standing outside but we cannot be daunted by their extinguished. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

Scale Genetic Structure in a Tropical Montane Parrot Species

RESEARCH ARTICLE Limited Dispersal and Significant Fine - Scale Genetic Structure in a Tropical Montane Parrot Species Nadine Klauke1*, H. Martin Schaefer1, Michael Bauer1, Gernot Segelbacher2 1 Animal Ecology and Evolution, Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 2 Wildlife Ecology and Management, Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Tropical montane ecosystems are biodiversity hotspots harbouring many endemics that are confined to specific habitat types within narrow altitudinal ranges. While deforestation put these ecosystems under threat, we still lack knowledge about how heterogeneous environ- OPEN ACCESS ments like the montane tropics promote population connectivity and persistence. We investi- Citation: Klauke N, Schaefer HM, Bauer M, gated the fine-scale genetic structure of the two largest subpopulations of the endangered Segelbacher G (2016) Limited Dispersal and El Oro parakeet (Pyrrhura orcesi) endemic to the Ecuadorian Andes. Specifically, we Significant Fine - Scale Genetic Structure in a assessed the genetic divergence between three sites separated by small geographic dis- Tropical Montane Parrot Species. PLoS ONE 11 (12): e0169165. doi:10.1371/journal. tances but characterized by a heterogeneous habitat structure. Although geographical dis- pone.0169165 tances between sites are small (3±17 km), we found genetic differentiation between all Editor: Don A. Driscoll, Deakin University, sites. Even though dispersal capacity is generally high in parrots, our findings indicate that Australia, AUSTRALIA dispersal is limited even on this small geographic scale. Individual genotype assignment Received: March 25, 2015 revealed similar genetic divergence across a valley (~ 3 km distance) compared to a contin- uous mountain range (~ 13 km distance). -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Some Venezuelan Wild Bird Species That Box Against Their Own Reflections

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 26(3): 192–195. SHORt-COMMUNICATIONARTICLE September 2018 Some Venezuelan wild bird species that box against their own reflections Carlos Verea1,2 1 Universidad Central de Venezuela, Facultad de Agronomía, Instituto de Zoología Agrícola, Apartado 4579, Maracay 2101–A, estado Aragua, Venezuela. 2 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 02 July 2018. Accepted on 22 October 2018. ABSTRACT: Data about shadow boxing behavior in Neotropical wild birds is almost absent. A total of 16 novel wild bird species were found performing shadow boxing behavior in northern Venezuela. Families Trochilidae, Picidae, Tyrannidae, Corvidae, Turdidae, Mimidae, Thraupidae, Emberizidae, and Parulidae were represented, with Trochilidae and Tyrannidae reported for the first time. Reflecting surfaces were car components, home windows, glass sliding doors, and a stainless steel pot. As expected, date of records and breeding season information matched for all species. Nonetheless, the White-vented Plumeleteer Chalybura buffonii behavior does not appear to be related to its breeding condition. Instead, this species shadow box to defend a food source. While most birds shadow box with their beak, wings and feet, Trochilidae species developed aerial displays, and beat their reflections with the breast and beak. Two records involved female individuals. Recorded information noticeably improves the previous knowledge of avian shadow boxing behavior in Venezuela and the Neotropical region. KEY-WORDS: agonistic behavior, avian behavior, -

Introduction to Tropical Biodiversity, October 14-22, 2019

INTRODUCTION TO TROPICAL BIODIVERSITY October 14-22, 2019 Sponsored by the Canopy Family and Naturalist Journeys Participants: Linda, Maria, Andrew, Pete, Ellen, Hsin-Chih, KC and Cathie Guest Scientists: Drs. Carol Simon and Howard Topoff Canopy Guides: Igua Jimenez, Dr. Rosa Quesada, Danilo Rodriguez and Danilo Rodriguez, Jr. Prepared by Carol Simon and Howard Topoff Our group spent four nights in the Panamanian lowlands at the Canopy Tower and another four in cloud forest at the Canopy Lodge. In very different habitats, and at different elevations, conditions were optimal for us to see a great variety of birds, butterflies and other insects and arachnids, frogs, lizards and mammals. In general we were in the field twice a day, and added several night excursions. We also visited cultural centers such as the El Valle Market, an Embera Village, the Miraflores Locks on the Panama Canal and the BioMuseo in Panama City, which celebrates Panamanian biodiversity. The trip was enhanced by almost daily lectures by our guest scientists. Geoffroy’s Tamarin, Canopy Tower, Photo by Howard Topoff Hot Lips, Canopy Tower, Photo by Howard Topoff Itinerary: October 14: Arrival and Orientation at Canopy Tower October 15: Plantation Road, Summit Gardens and local night drive October 16: Pipeline Road and BioMuseo October 17: Gatun Lake boat ride, Emberra village, Summit Ponds and Old Gamboa Road October 18: Gamboa Resort grounds, Miraflores Locks, transfer from Canopy Tower to Canopy Lodge October 19: La Mesa and Las Minas Roads, Canopy Adventure, Para Iguana -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 137 No. 1 (Online) ISSN 2513-9894 (Online) March 2017 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS See also BOC website: http://www.boc-online.org BOC MEETINGS are open to all, not just BOC members, and are free. Evening meetings are in an upstairs room at The Barley Mow, 104 Horseferry Road, Westminster, London SW1P 2EE. The nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park; and the 507 bus, which runs from Victoria to Waterloo, stops nearby. For maps, see http://www.markettaverns.co.uk/the_barley_mow.html or ask the Chairman for directions. The cash bar opens at 6.00 pm and those who wish to eat after the meeting can place an order. The talk will start at 6.30 pm and, with questions, will last c.1 hour. Please note that in 2017 evening meetings will take place on a Monday, rather than Tuesday as hitherto. It would be very helpful if those intending to come can notify the Chairman no later than the day before the meeting. Monday 13 March 2017—6.30 pm—Julian Hume—In search of the dwarf emu: extinct emus of Australian islands. Abstract: King Island and Kangaroo Island were once home to endemic species of dwarf emu that became extinct in the early 19th century. Emu egg shells have also been found on Flinders Island, which suggests that another emu species may have formerly occurred there. In 1906 J. A. Kershaw undertook a survey of King Island searching for fossil specimens and found emu bones in sand dunes in the south of the island. -

The Following Is a Section of a Document Properly Cited As: Snyder, N., Mcgowan, P., Gilardi, J., and Grajal, A. (Eds.) (2000) P

The following is a section of a document properly cited as: Snyder, N., McGowan, P., Gilardi, J., and Grajal, A. (eds.) (2000) Parrots. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. x + 180 pp. © 2000 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the World Parrot Trust It has been reformatted for ease of use on the internet . The resolution of the photographs is considerably reduced from the printed version. If you wish to purchase a printed version of the full document, please contact: IUCN Publications Unit 219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK. Tel: (44) 1223 277894 Fax: (44) 1223 277175 Email: [email protected] The World Parrot Trust World Parrot Trust UK World Parrot Trust USA Order on-line at: Glanmor House PO Box 353 www.worldparrottrust.org Hayle, Cornwall Stillwater, MN 55082 TR27 4HB, United Kingdom Tel: 651 275 1877 Tel: (44) 1736 753365 Fax: 651 275 1891 Fax (44) 1736 751028 Island Press Box 7, Covelo, California 95428, USA Tel: 800 828 1302, 707 983 6432 Fax: 707 983 6414 E-mail: [email protected] Order on line: www.islandpress.org The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or the Species Survival Commission. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. Copyright: © 2000 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the World Parrot Trust Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

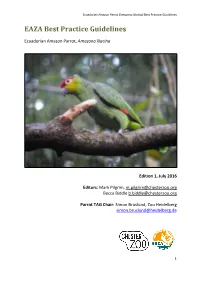

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines for the Ecuadorian Amazon Parrot

Ecuadorian Amazon Parrot (Amazona lilacina) Best Practice Guidelines EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Ecuadorian Amazon Parrot, Amazona lilacina Edition 1, July 2016 Editors: Mark Pilgrim, [email protected] Becca Biddle [email protected] Parrot TAG Chair: Simon Bruslund, Zoo Heidelberg [email protected] 1 Ecuadorian Amazon Parrot (Amazona lilacina) Best Practice Guidelines EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Disclaimer Copyright (July 2016) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Parrot TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Not to Be Missed!

22nd to 25th SEPTEMBER 2014 TENERIFE SPAIN 19 Speakers - 19 topics Not to be missed! Dr. Auguste v. Bayern studied biology at the German “Keynote Speaker” Ludwig-Maximilans-University in Munich and at the University of Cape Town in South Africa from which she graduated in 2002 with a BSc in Zoology. Since 2008 she has worked as a post-doctoral research associate with Prof. Alex Kacelnik in the Behavioural Ecology Research Group at the University of Oxford. Besides managing the Oxford New Caledonian crow colony and the area of corvid cognition research she also leads the Avian Cognition research team. Topic: Avian Cognition: Innovative problem solving abilities of parrots and corvids Morten Bruun-Rasmussen, Denmark, is educated as an engineer and is running a consultancy company in the field of Medical Informatics and Quality Development. Morten is a private breeder of parrots and has kept parrots since he was a small boy and today has than more than 40 years’ experience in breeding parrots. He has made a lot effort to breed the rare Golden -shouldered Parakeet with an estimated breeding Image donated by the artist Mrs. Ria Winters population of less than 2,000 birds in the wild. Topic: What can we learn from scientific studies to improve the breeding of the Golden-shouldered Parakeet? Prof. Rob Heinsohn is a research scientist at the Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian Rudolf Christian, Germany, started National University. His 25 year academic breeding pigeons at the age of 9. He has career has been marked by long term, and kept this hobby until today. -

Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (Custom Tour)

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador 18th November – 6th December 2019 Hummingbirds were a big feature of this tour; with 58 hummingbird species seen, that included some very rare, restricted range species, like this Blue-throated Hillstar. This critically-endangered species was only described in 2018, following its discovery a year before that, and is currently estimated to number only 150 individuals. This male was seen multiple times during an afternoon at this beautiful, high Andean location, and was widely voted by participants as one of the overall highlights of the tour (Sam Woods). Tour Leader: Sam Woods Photos: Thanks to participant Chris Sloan for the use of his photos in this report. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador ranks as one of the most popular South American tours among professional bird guides (not a small claim on the so-called “Bird Continent”!); the reasons are simple, and were all experienced firsthand on this tour… Ecuador is one of the top four countries for bird species in the World; thus high species lists on any tour in the country are a given, this is especially true of the south of Ecuador. To illustrate this, we managed to record just over 600 bird species on this trip (601) of less than three weeks, including over 80 specialties. This private group had a wide variety of travel experience among them; some had not been to South America at all, and ended up with hundreds of new birds, others had covered northern Ecuador before, but still walked away with 120 lifebirds, and others who’d covered both northern Ecuador and northern Peru, (directly either side of the region covered on this tour), still had nearly 90 new birds, making this a profitable tour for both “veterans” and “South American Virgins” alike.