Mathematical Cut-And-Paste: an Introduction to the Topology of Surfaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note on 6-Regular Graphs on the Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected]

Theory and Applications of Graphs Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 5 2017 Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected] Naoki Matsumoto Seikei University, [email protected] Atsuhiro Nakamoto Yokohama National University, [email protected] Takayuki Nozawa [email protected] Hiroki Seno [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag Part of the Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons Recommended Citation Kasai, Michiko; Matsumoto, Naoki; Nakamoto, Atsuhiro; Nozawa, Takayuki; Seno, Hiroki; and Takiguchi, Yosuke (2017) "Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle," Theory and Applications of Graphs: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.20429/tag.2017.040105 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theory and Applications of Graphs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Authors Michiko Kasai, Naoki Matsumoto, Atsuhiro Nakamoto, Takayuki Nozawa, Hiroki Seno, and Yosuke Takiguchi This article is available in Theory and Applications of Graphs: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 Kasai et al.: 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle Abstract Altshuler [1] classified 6-regular graphs on the torus, but Thomassen [11] and Negami [7] gave different classifications for 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle. In this note, we unify those two classifications, pointing out their difference and similarity. -

Hydraulic Cylinder Replacement for Cylinders with 3/8” Hydraulic Hose Instructions

HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS INSTALLATION TOOLS: INCLUDED HARDWARE: • Knife or Scizzors A. (1) Hydraulic Cylinder • 5/8” Wrench B. (1) Zip-Tie • 1/2” Wrench • 1/2” Socket & Ratchet IMPORTANT: Pressure MUST be relieved from hydraulic system before proceeding. PRESSURE RELIEF STEP 1: Lower the Power-Pole Anchor® down so the Everflex™ spike is touching the ground. WARNING: Do not touch spike with bare hands. STEP 2: Manually push the anchor into closed position, relieving pressure. Manually lower anchor back to the ground. REMOVAL STEP 1: Remove the Cylinder Bottom from the Upper U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 1 or 2 NOTE: For Blade models, push bottom of cylinder up into U-Channel and slide it forward past the Ram Spacers to remove it. Upper U-Channel Upper U-Channel Cylinder Bottom 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Ram 1/2” Tools Spacers Cylinder Bottom If Ram-Spacers fall out Older models have (1) long & (1) during removal, push short Ram Spacer. Ram Spacers 1/2” Tools bushings in to hold MUST be installed on the same side Figure 1 Figure 2 them in place. they were removed. Blade Models Pro/Spn Models Need help? Contact our Customer Service Team at 1 + 813.689.9932 Option 2 HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS STEP 2: Remove the Cylinder Top from the Lower U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 3 or 4 Lower U-Channel Lower U-Channel 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Cylinder Top Cylinder Top Figure 3 Figure 4 Blade Models Pro/SPN Models STEP 3: Disconnect the UP Hose from the Hydraulic Cylinder Fitting by holding the 1/2” Wrench 5/8” Wrench Cylinder Fitting Base with a 1/2” wrench and turning the Hydraulic Hose Fitting Cylinder Fitting counter-clockwise with a 5/8” wrench. -

Surfaces and Fundamental Groups

HOMEWORK 5 — SURFACES AND FUNDAMENTAL GROUPS DANNY CALEGARI This homework is due Wednesday November 22nd at the start of class. Remember that the notation e1; e2; : : : ; en w1; w2; : : : ; wm h j i denotes the group whose generators are equivalence classes of words in the generators ei 1 and ei− , where two words are equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by inserting 1 1 or deleting eiei− or ei− ei or by inserting or deleting a word wj or its inverse. Problem 1. Let Sn be a surface obtained from a regular 4n–gon by identifying opposite sides by a translation. What is the Euler characteristic of Sn? What surface is it? Find a presentation for its fundamental group. Problem 2. Let S be the surface obtained from a hexagon by identifying opposite faces by translation. Then the fundamental group of S should be given by the generators a; b; c 1 1 1 corresponding to the three pairs of edges, with the relation abca− b− c− coming from the boundary of the polygonal region. What is wrong with this argument? Write down an actual presentation for π1(S; p). What surface is S? Problem 3. The four–color theorem of Appel and Haken says that any map in the plane can be colored with at most four distinct colors so that two regions which share a com- mon boundary segment have distinct colors. Find a cell decomposition of the torus into 7 polygons such that each two polygons share at least one side in common. Remark. -

Simple Infinite Presentations for the Mapping Class Group of a Compact

SIMPLE INFINITE PRESENTATIONS FOR THE MAPPING CLASS GROUP OF A COMPACT NON-ORIENTABLE SURFACE RYOMA KOBAYASHI Abstract. Omori and the author [6] have given an infinite presentation for the mapping class group of a compact non-orientable surface. In this paper, we give more simple infinite presentations for this group. 1. Introduction For g ≥ 1 and n ≥ 0, we denote by Ng,n the closure of a surface obtained by removing disjoint n disks from a connected sum of g real projective planes, and call this surface a compact non-orientable surface of genus g with n boundary components. We can regard Ng,n as a surface obtained by attaching g M¨obius bands to g boundary components of a sphere with g + n boundary components, as shown in Figure 1. We call these attached M¨obius bands crosscaps. Figure 1. A model of a non-orientable surface Ng,n. The mapping class group M(Ng,n) of Ng,n is defined as the group consisting of isotopy classes of all diffeomorphisms of Ng,n which fix the boundary point- wise. M(N1,0) and M(N1,1) are trivial (see [2]). Finite presentations for M(N2,0), M(N2,1), M(N3,0) and M(N4,0) ware given by [9], [1], [14] and [16] respectively. Paris-Szepietowski [13] gave a finite presentation of M(Ng,n) with Dehn twists and arXiv:2009.02843v1 [math.GT] 7 Sep 2020 crosscap transpositions for g + n > 3 with n ≤ 1. Stukow [15] gave another finite presentation of M(Ng,n) with Dehn twists and one crosscap slide for g + n > 3 with n ≤ 1, applying Tietze transformations for the presentation of M(Ng,n) given in [13]. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

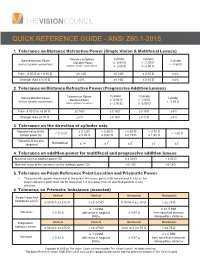

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization Hans Havlicek and Klaus List, Institut fur¨ Geometrie, TU Wien 3 We describe and visualize the chains of the 3-dimensional chain geometry over the ring R("), " = 0. MSC 2000: 51C05, 53A20. Keywords: chain geometry, Laguerre geometry, affine space, twisted cubic. 1 Introduction The aim of the present paper is to discuss in some detail the Laguerre geometry (cf. [1], [6]) which arises from the 3-dimensional real algebra L := R("), where "3 = 0. This algebra generalizes the algebra of real dual numbers D = R("), where "2 = 0. The Laguerre geometry over D is the geometry on the so-called Blaschke cylinder (Figure 1); the non-degenerate conics on this cylinder are called chains (or cycles, circles). If one generator of the cylinder is removed then the remaining points of the cylinder are in one-one correspon- dence (via a stereographic projection) with the points of the plane of dual numbers, which is an isotropic plane; the chains go over R" to circles and non-isotropic lines. So the point space of the chain geometry over the real dual numbers can be considered as an affine plane with an extra “improper line”. The Laguerre geometry based on L has as point set the projective line P(L) over L. It can be seen as the real affine 3-space on L together with an “improper affine plane”. There is a point model R for this geometry, like the Blaschke cylinder, but it is more compli- cated, and belongs to a 7-dimensional projective space ([6, p. -

1 University of California, Berkeley Physics 7A, Section 1, Spring 2009

1 University of California, Berkeley Physics 7A, Section 1, Spring 2009 (Yury Kolomensky) SOLUTIONS TO THE SECOND MIDTERM Maximum score: 100 points 1. (10 points) Blitz (a) hoop, disk, sphere This is a set of simple questions to warm you up. The (b) disk, hoop, sphere problem consists of five questions, 2 points each. (c) sphere, hoop, disk 1. Circle correct answer. Imagine a basketball bouncing on a court. After a dozen or so (d) sphere, disk, hoop bounces, the ball stops. From this, you can con- (e) hoop, sphere, disk clude that Answer: (d). The object with highest moment of (a) Energy is not conserved. inertia has the largest kinetic energy at the bot- (b) Mechanical energy is conserved, but only tom, and would reach highest elevation. The ob- for a single bounce. ject with the smallest moment of inertia (sphere) (c) Total energy in conserved, but mechanical will therefore reach lowest altitude, and the ob- energy is transformed into other types of ject with the largest moment of inertia (hoop) energy (e.g. heat). will be highest. (d) Potential energy is transformed into kinetic 4. A particle attached to the end of a massless rod energy of length R is rotating counter-clockwise in the (e) None of the above. horizontal plane with a constant angular velocity ω as shown in the picture below. Answer: (c) 2. Circle correct answer. In an elastic collision ω (a) momentum is not conserved but kinetic en- ergy is conserved; (b) momentum is conserved but kinetic energy R is not conserved; (c) both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved; (d) neither kinetic energy nor momentum is Which direction does the vector ~ω point ? conserved; (e) none of the above. -

Graphs on Surfaces, the Generalized Euler's Formula and The

Graphs on surfaces, the generalized Euler's formula and the classification theorem ZdenˇekDvoˇr´ak October 28, 2020 In this lecture, we allow the graphs to have loops and parallel edges. In addition to the plane (or the sphere), we can draw the graphs on the surface of the torus or on more complicated surfaces. Definition 1. A surface is a compact connected 2-dimensional manifold with- out boundary. Intuitive explanation: • 2-dimensional manifold without boundary: Each point has a neighbor- hood homeomorphic to an open disk, i.e., \locally, the surface looks at every point the same as the plane." • compact: \The surface can be covered by a finite number of such neigh- borhoods." • connected: \The surface has just one piece." Examples: • The sphere and the torus are surfaces. • The plane is not a surface, since it is not compact. • The closed disk is not a surface, since it has a boundary. From the combinatorial perspective, it does not make sense to distinguish between some of the surfaces; the same graphs can be drawn on the torus and on a deformed torus (e.g., a coffee mug with a handle). For us, two surfaces will be equivalent if they only differ by a homeomorphism; a function f :Σ1 ! Σ2 between two surfaces is a homeomorphism if f is a bijection, continuous, and the inverse f −1 is continuous as well. In particular, this 1 implies that f maps simple continuous curves to simple continuous curves, and thus it maps a drawing of a graph in Σ1 to a drawing of the same graph in Σ2. -

The Hairy Klein Bottle

Bridges 2019 Conference Proceedings The Hairy Klein Bottle Daniel Cohen1 and Shai Gul 2 1 Dept. of Industrial Design, Holon Institute of Technology, Israel; [email protected] 2 Dept. of Applied Mathematics, Holon Institute of Technology, Israel; [email protected] Abstract In this collaborative work between a mathematician and designer we imagine a hairy Klein bottle, a fusion that explores a continuous non-vanishing vector field on a non-orientable surface. We describe the modeling process of creating a tangible, tactile sculpture designed to intrigue and invite simple understanding. Figure 1: The hairy Klein bottle which is described in this manuscript Introduction Topology is a field of mathematics that is not so interested in the exact shape of objects involved but rather in the way they are put together (see [4]). A well-known example is that, from a topological perspective a doughnut and a coffee cup are the same as both contain a single hole. Topology deals with many concepts that can be tricky to grasp without being able to see and touch a three dimensional model, and in some cases the concepts consists of more than three dimensions. Some of the most interesting objects in topology are non-orientable surfaces. Séquin [6] and Frazier & Schattschneider [1] describe an application of the Möbius strip, a non-orientable surface. Séquin [5] describes the Klein bottle, another non-orientable object that "lives" in four dimensions from a mathematical point of view. This particular manuscript was inspired by the hairy ball theorem which has the remarkable implication in (algebraic) topology that at any moment, there is a point on the earth’s surface where no wind is blowing. -

Natural Cadmium Is Made up of a Number of Isotopes with Different Abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd

CLASSROOM Natural cadmium is made up of a number of isotopes with different abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd 112 (24.13%), Cd113 (12.22%), Cd114(28.73%), Cd116 (7.49%). Of these Cd113 is the main neutron absorber; it has an absorption cross section of 2065 barns for thermal neutrons (a barn is equal to 10–24 sq.cm), and the cross section is a measure of the extent of reaction. When Cd113 absorbs a neutron, it forms Cd114 with a prompt release of γ radiation. There is not much energy release in this reaction. Cd114 can again absorb a neutron to form Cd115, but the cross section for this reaction is very small. Cd115 is a β-emitter C V Sundaram, National (with a half-life of 53hrs) and gets transformed to Indium-115 Institute of Advanced Studies, Indian Institute of Science which is a stable isotope. In none of these cases is there any large Campus, Bangalore 560 012, release of energy, nor is there any release of fresh neutrons to India. propagate any chain reaction. Vishwambhar Pati The Möbius Strip Indian Statistical Institute Bangalore 560059, India The Möbius strip is easy enough to construct. Just take a strip of paper and glue its ends after giving it a twist, as shown in Figure 1a. As you might have gathered from popular accounts, this surface, which we shall call M, has no inside or outside. If you started painting one “side” red and the other “side” blue, you would come to a point where blue and red bump into each other.