Author Under Sail Jay Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excerpts from Popular Books by Jack London the Call of the Wild Chapter I

Excerpts from Popular Books by Jack London The Call of the Wild Chapter I. Into the Primitive “Old longings nomadic leap, Chafing at custom’s chain; Again from its brumal sleep Wakens the ferine strain.” Buck did not read the newspapers, or he would have known that trouble was brewing, not alone for himself, but for every tide-water dog, strong of muscle and with warm, long hair, from Puget Sound to San Diego. Because men, groping in the Arctic darkness, had found a yellow metal, and because steamship and transportation companies were booming the find, thousands of men were rushing into the Northland. These men wanted dogs, and the dogs they wanted were heavy dogs, with strong muscles by which to toil, and furry coats to protect them from the frost. Figure 1: Jack London, 1905. Photo: Public White Fang Domain Chapter I—The Trail of the Meat Dark spruce forest frowned on either side the frozen waterway. The trees had been stripped by a recent wind of their white covering of frost, and they seemed to lean towards each other, black and ominous, in the fading light. A vast silence reigned over the land. The land itself was a desolation, lifeless, without movement, so lone and cold that the spirit of it was not even that of sadness. There was a hint in it of laughter, but of a laughter more terrible than any sadness—a laughter that was mirthless as the smile of the sphinx, a laughter cold as the frost and partaking of the grimness of infallibility. -

Jack London State Historic Park for School Groups

Jack London State Historic Park Self-Guided Tour Packet for School Groups Contents Introductions and Park Regulations 1 Map of Historic Sites 4 A Brief Biography of Jack London’s life 5 Chronological booklist 9 Beauty Ranch 10 The London’s Cottage 13 House of Happy Walls Museum 15 The Wolf House Ruins 17 Jack and Charmian’s Gravesite 19 Appendix (includes suggested lessons & 21 activities) Welcome to Jack London State Historic Park! Thank you for choosing our site as your field trip destination. At Jack London State Historic Park, we believe passionately in the power of learning through experience and know that first-hand encounters with history and the natural world can inspire and foster a desire for life-long learning. We want to support you and your efforts to create a memorable field trip for your students while you are here. This pre-visit guide is designed as a helpful resource for educators and contains maps and information about the park, as well as historical information on Jack London’s life and legacy. Each historical feature and building on the site has its own chapter of information and points of interest. In the appendix you will find a few suggested lessons and activities that enhance certain aspects of the park and speak to several learning standards. Park Video: Teachers and group leaders can watch 20-minute orientation video that describes features of the park including historic film footage and subtitles for the hearing impaired. You will find this video on Youtube at https://youtu.be/Xqa7xb0exes We hope these materials -

Jack London - Free Online Library

Jack London - Free Online Library London's youth was marked by poverty. 3 many years later he left the girl and their a pair of daughters, eventually in order to marry Charmian Kittredge, an editor and outdoorswoman. I shall use my time. You can't watch for inspiration. Within 1894 he ended up being arrested in try what your woman says Niagara Falls as well as jailed with regard to vagrancy. Inside the midst of a bitter separation in 1904, London traveled to Korea as a correspondent for Hearst's newspapers to pay for the actual war among Russia and also Japan (1904-05). Within 1900 he married Elisabeth (Bess) Maddern; their house became a new battle field among Bess as well as London's mother Flora. He didn't stop trying even in the particular program of his travels along with drinking periods. His guide about the economic degradation in the poor, the People of the Abyss (1903), was a surprise achievement in the U.S. He died about November 22, 1916, officially of gastro-intestinal uremia. London had early built his system of producing a new every day quota regarding thousand words. He ended up being deserted by simply his father, "Professor" William Henry Chaney, an itinerant astrologer, along with raised within Oakland simply by his mother Flora Wellman, a new audio teacher along with spiritualist. London's very first novel, The Particular Son with the Wolf, appeared within 1900. Upon the particular voyage he started for you to write Martin Eden. His early stories appeared inside the Overland Month For You To Month along with Atlantic Monthly. -

The Call: Spring-Summer 2006

Spring /Summer 2006 Volume XVII, No. 1 THE CALL The Magazine of the Jack London Society Inside This Issue: A Remembrance of Winnie 2 Winifred Kingman Dies At Age 85 3 Recent London Publications 3 Eighth Biennial Symposium: Alaska 4 Jack London’s Palace of Fine Arts 5 And “The Hussy” News and Notes 9 Page 2 The Call A REMEMBRANCE OF WINNIE The Jack London Society G ARY RIEDL President No doubt all who knew Winnie will instantly recall with a pang of loss Donna Campbell her warm receptionreception not only to her friends but to all visitors, particularly Washington State University those whose research interests led them to seek out the wonderful resources available in the JL Research Center in Glen Ellen. As we all know, the center was put together by Winnie and her beloved Russ, demonstrating Executive Coordinator their combined efforts to collect and organize everything they could find on Jeanne C. Reesman Jack London. In the process, Winnie became an authority on London, his University of Texas at San Antonio home, his family, his travels, and his place in the literature of California and the world. Everyone who visited the little Research Center will recall a Advisory Board sense of surprise at the vast amount of information—all of it useful to peo- Sam S. Baskett ple trying to understand an author whose work has fluctuated between Michigan State University world-wide accolades and nominal acceptance. Thanks though in no small Lawrence I. Berkove part to the efforts of the Winnie and Russ, over the last 30 years London University of Michigan-Dearborn has emerged as the important artist he knew himself to be. -

The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Jack London **The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Iron Heel by Jack London** #39 in our series by Jack London Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Iron Heel by Jack London January, 1998 [Etext #1164] **The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Iron Heel by Jack London** *****This file should be named irnhl10.txt or irnhl10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, irnhl11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, irnhl10a.txt. This etext was prepared by Donald Lainson, [email protected]. Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we do NOT keep these books in compliance with any particular paper edition, usually otherwise. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. -

The Call of the Wild Extract

The Call of the Wild and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Other Stories Jack London Illustrations by Ian Beck ALMA CLASSICS AlmA ClAssiCs an imprint of AlmA books ltd 3 Castle Yard Richmond Surrey TW10 6TF United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com ‘The Call of the Wild’ first published in 1903; ‘Brown Wolf’ first pub- lished in 1906; ‘That Spot’ first published in 1908; ‘To Build a Fire’ first published in 1908 This edition first published by Alma Classics in 2020 Cover and inside illustrations © Ian Beck, 2020 Extra Material © Alma Books Ltd Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-844-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents The Call of the Wild and Other Stories 1 The Call of the Wild 3 Brown Wolf 107 That Spot 127 To Build a Fire 139 Notes 159 Extra Material for Young Readers 161 The Writer 163 The Book 165 The Characters 167 Other Animal Adventure Stories 169 Test Yourself 172 Glossary 175 The Call of the Wild and Other Stories THE CALL OF THE WILD 1 Into the Primitive Old longings nomadic leap, Chafing at custom’s chain; Again from its brumal sleep Wakens the ferine strain.* uCk did not reAd the newspapers, or he would B have known that trouble was brewing – not alone for himself, but for every tidewater dog, strong of muscle and with warm, long hair, from Puget Sound to San Diego. -

A Rip in the Social Fabric: Revolution, Industrial Workers of the World, and the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 in American Literature, 1908-1927

i A RIP IN THE SOCIAL FABRIC: REVOLUTION, INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD, AND THE PATERSON SILK STRIKE OF 1913 IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1908-1927 ___________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ___________________________________________________________________________ by Nicholas L. Peterson August, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Philip R. Yannella, English Susan Wells, English David Waldstreicher, History ii ABSTRACT In 1913, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) led a strike of silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey. Several New York intellectuals took advantage of Paterson’s proximity to New York to witness and participate in the strike, eventually organizing the Paterson Pageant as a fundraiser to support the strikers. Directed by John Reed, the strikers told their own story in the dramatic form of the Pageant. The IWW and the Paterson Silk Strike inspired several writers to relate their experience of the strike and their participation in the Pageant in fictional works. Since labor and working-class experience is rarely a literary subject, the assertiveness of workers during a strike is portrayed as a catastrophic event that is difficult for middle-class writers to describe. The IWW’s goal was a revolutionary restructuring of society into a worker-run co- operative and the strike was its chief weapon in achieving this end. Inspired by such a drastic challenge to the social order, writers use traditional social organizations—religion, nationality, and family—to structure their characters’ or narrators’ experience of the strike; but the strike also forces characters and narrators to re-examine these traditional institutions in regard to the class struggle. -

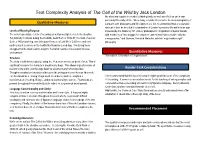

Text Complexity Analysis of the Call of the Wild by Jack London

Text Complexity Analysis of The Call of the Wild by Jack London the story and require the reader to think globally as well as reflect on one’s own personal philosophy of life. Since many consider this novel to be an autobiography of Qualitative Measures London’s own philosophy and life experiences, it is recommended that a reasonable amount of time be devoted to examination of London’s personal life and how he was Levels of Meaning/Purpose: impacted by the following 19th century philosophers: Englishmen Charles Darwin, The novel has multiple levels of meaning as well as multiple levels to the storyline. with his theory of “the struggle for existence” and Herbert Spencer with “only the Set primarily in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896-97, the main character strong survive,” and German, Freidrich Nietsche, with his “might makes right” Buck, a 140 pound dog, was kidnapped from a civilized life in California and sent philosophy. north to learn to survive in the hostile Northland as a sled dog. It is during these struggles that he must learn to adapt to the harsh realities of survival in his new environment. QuaQualitativentitative Measures Measures The lexile is 1010 which is 7.8 grade level. Structure: The story is told chronologically, using the 3rd person omniscient point of view. This is significant because the characters are primarily dogs. This allows a greater sense of realism to the story, and the dogs begin to assume many human qualities. Reader-Task Considerations Though somewhat unconventional because the protagonist is not human, this book can be viewed as a coming of age novel since Buck needs to complete a It is recommended that this novel be used in eighth grade because of the complexity transformation of setting, lifestyle, and personal morality to survive. -

The Notion of Chance in the Narratives of Jack London and R. L. Stevenson

The Notion of Chance in the Narratives of Jack London and R. L. Stevenson Škunca, Iva Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:897345 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Iva Škunca The Notion of Chance in the Narratives of Jack London and Robert Louis Stevenson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the B.A. in English Language and Literature and Italian Language and Literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat PhD Rijeka, September 2017 ABSTRACT Both Jack London and Robert Louis Stevenson are famous for a variety of literary work they produced in a relatively short time span. As we can establish a link between the two vagabond authors who both sought an escape from the routine and the conventions of the societies they only seemingly belonged to, we can also establish a connection between some of their most brilliant works, mainly those characterised by elements of adventure fiction. This paper deals with the most prominent themes and motifs of the authors’ literary works, as well as the problems and conflicts which arise from the analysis of their work. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON’S AND JACK LONDON’S LITERARY WORK ........... -

The Reinvention of the Primitive in Naturalist and Modernist Literature"

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2001 A living lump of appetites': the reinvention of the primitive in naturalist and modernist literature" Gina M. Rossetti University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Rossetti, Gina M., "A living lump of appetites': the reinvention of the primitive in naturalist and modernist literature". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6378 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Gina M. Rossetti entitled "A living lump of appetites': the reinvention of the primitive in naturalist and modernist literature"." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Gina M. Rossetti entitled" 'A Living Lump of Appetites': The Reinvention of the Primitive in Naturalist and Modernist Literature." I have examined the final paper copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

A Study of the Call of the Wild from the Perspective of Greimas' Semiotic Square Theory

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 6, No. 8, pp. 1706-1712, August 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0608.27 A Study of The Call of the Wild from the Perspective of Greimas’ Semiotic Square Theory Weiguo Si College of International Studies, Southwest University, China Abstract—Algirdas Julien Greimas is the most influential French structural linguist. He puts forward the profound semiotic square, which has been widely used in the research of literature to reveal the implied meanings and relationship between complex things. The Call of the Wild written by the American naturalistic writer Jack London is his representative work. It has been studied by a lot of scholars from different perspectives since its birth. This thesis applies semiotic square theory, further classifying characters in this novel: Buck is the X; Trafficker is the Anti X; Spitz is the Non X; John is the Non anti X. By the use of the comparative analysis method and the textual close-reading method this thesis analyzes the plot and the deep structure of The Call of the Wild. The result of this thesis is as follows: the relation between Buck and the traffickers is oppression and resistance; the relation between Buck and Spitz is competitor; the relation between Buck and John Thornton is protective and grateful. Through classifying the action elements, readers can see the narrative structure of this novel, which is not stated flatly but with its own unique tortuosity and complexity and it is conducive to deepening their understanding about the artistry and profundity of this novel, and help readers better understand the Superman image of Buck, the main character in The Call of the Wild, and provide them with the effective example in appreciating Jack London’s other literary works. -

Debbie Lopez

DEBBIE LOPEZ The University of Texas at San Antonio Dept. of English, Classics, Philosophy, San Antonio, TX 78249 (210) 458-5973 [email protected] Revised January 23, 2009 ________________________________________________________________________ Academic Training March, 1994 Ph.D., Harvard University, Department of English and American Literature and Language. Distinction conferred. Dissertation received Howard Mumford Jones Prize. 1987 A.M., Harvard University, Department of English and American Literature and Language. 1981 M.A., Middlebury College (Bread Loaf School of English). 1977 B.A. The University of the South, Department of English. Summer, 1976 University College, Oxford University, Oxford, U.K. Teaching Positions Held September 2008-February 2009 Visiting Fulbright Scholar, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece 1999-Present Associate Professor, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Department of English, Classics, and Philosophy 2008-2009 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, Fulbright Lecturer. 1993-1999 Assistant Professor, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Division of English, Classics, Philosophy, and Communication. 1988-1993 Teaching Fellow, Harvard University, Department of English and American Literature and Language. 1984-1986 Part-time Instructor in Composition and American Literature and Instructor in the Writing Laboratory at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. 1984-1986 Part-time Instructor in Composition, Birmingham Southern College, Birmingham, Alabama. Non-University Positions Related to Field 1992-1993 Research Assistant to Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Harvard University 1 1987-1988 Research Assistant to Professor Marjorie Garber, Harvard University. 1981-1983 Staff Writer and Editor, Alabama Public Television Publications Book: Lopez, Debbie. Taking the Fall: Lilith and Lamia in the New World Eden. (Book manuscript) Refereed Journal Articles: Lopez, Debbie.