Nation, State, Nation-State Nation, State, Nation-State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

The Catholic Church and the Reproductive Health Bill Debate: the Philippine Experience

bs_bs_banner HeyJ LV (2014), pp. 1044–1055 THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH BILL DEBATE: THE PHILIPPINE EXPERIENCE ERIC MARCELO O. GENILO, SJ Loyola School of Theology, Philippines The leadership of the Church in the Philippines has historically exercised a powerful influence on politics and social life. The country is at least 80% Catholic and there is a deeply ingrained cultural deference for clergy and religious. Previous attempts in the last 14 years to pass a reproductive health law have failed because of the opposition of Catholic bishops. Thus the recent passage of the ‘Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012’ (R.A. 10354) was viewed by some Filipinos as a stunning failure for the Church and a sign of its diminished influence on Philippine society. This article proposes that the Church’s engagement in the reproductive health bill (RH Bill) debate and the manner of its discourse undermined its own campaign to block the law.1 The first part of the article gives a historical overview of the Church’s opposition to government family planning programs. The second part discusses key points of conflict in the RH Bill debate. The third part will examine factors that shaped the Church’s attitude and responses to the RH Bill. The fourth part will examine the effects of the debate on the Church’s unity, moral authority, and role in Philippine society. The fifth part will draw lessons for the Church and will explore paths that the Church community can take in response to the challenges arising from the law’s implementation. -

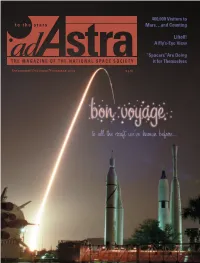

To All the Craft We've Known Before

400,000 Visitors to Mars…and Counting Liftoff! A Fly’s-Eye View “Spacers”Are Doing it for Themselves September/October/November 2003 $4.95 to all the craft we’ve known before... 23rd International Space Development Conference ISDC 2004 “Settling the Space Frontier” Presented by the National Space Society May 27-31, 2004 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Location: Clarion Meridian Hotel & Convention Center 737 S. Meridian, Oklahoma City, OK 73108 (405) 942-8511 Room rate: $65 + tax, 1-4 people Planned Programming Tracks Include: Spaceport Issues Symposium • Space Education Symposium • “Space 101” Advanced Propulsion & Technology • Space Health & Biology • Commercial Space/Financing Space Space & National Defense • Frontier America & the Space Frontier • Solar System Resources Space Advocacy & Chapter Projects • Space Law and Policy Planned Tours include: Cosmosphere Space Museum, Hutchinson, KS (all day Thursday, May 27), with Max Ary Oklahoma Spaceport, courtesy of Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority Oklahoma City National Memorial (Murrah Building bombing memorial) Omniplex Museum Complex (includes planetarium, space & science museums) Look for updates on line at www.nss.org or www.nsschapters.org starting in the fall of 2003. detach here ISDC 2004 Advance Registration Form Return this form with your payment to: National Space Society-ISDC 2004, 600 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E., Suite 201, Washington DC 20003 Adults: #______ x $______.___ Seniors/Students: #______ x $______.___ Voluntary contribution to help fund 2004 awards $______.___ Adult rates (one banquet included): $90 by 12/31/03; $125 by 5/1/04; $150 at the door. Seniors(65+)/Students (one banquet included): $80 by 12/31/03; $100 by 5/1/04; $125 at the door. -

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M

BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE for Human Development ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M. Guevarra St. corner Calbayog Extension Mandaluyong City Tel Nos. 584-25-01; Tel/Fax 470-41-51 E-mail: [email protected] Website: bbc.org.ph TABLE OF CONTENTS BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE MESSAGE OF NATIONAL CO-CHAIRMEN.....................................................1-2 FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ELECTION RESULTS............................ 3-4 STRATEGIC PLANNING OF THE EXCOM - OUTPUTS.....................................5-6 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITEE REPORT.................................................7-10 NATIONAL SECRETARIAT National Greening Program.................................................................8-10 Consultation Meeting with the CBCP Plenary Assembly........................10-13 CARDINAL SIN TRUST FUND FOR BUSINESS DISCIPLESHIP.......................23-24 CLUSTER/COMMITTEE REPORTS Formation of BBC Chapters..........................................................................13 Mary Belle S. Beluan Cluster on Labor & Employment................................................................23-24 Executive Director/Editor Committee on Social Justice & Agrarian Reform.....................................31-37 Coalition Against Corruption -BBC -LAIKO Government Procurement Monitoring Project.......................................................................................38-45 Replication of Government Procurement Monitoring............................46-52 -

Neo-Authoritarianism and the Contestation of White Identification in the US

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 23 (2021) Issue 1 Article 5 Neo-Authoritarianism and the Contestation of White Identification in the US Justin Gilmore University of California, Santa Cruz Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Gilmore, Justin. -

Jordan Peterson

Jordan Peterson It came from the Internet! From his heartfelt lectures, to his wild battles with academic leftists, to his enigmatic, all-beef diet (which is a real thing), YouTuber Jordan Peterson has captivated the minds of millions across the world, in person and online. He has especially drawn the notice of younger men with his mythological, scientific approach to moral life, so much so that Christian thinkers and leaders have struggled to understand the meaning of his rise to internet stardom. Responses to the Peterson phenomenon have been numerous and irreconcilable. Some call him a new conservative prophet, others a woman-hating prig. Still others call him an apologist for white supremacy and heteronormativity. Still others call him a hero of classical liberalism and champion of free speech and the open exchange of ideas. He’s even been called the high priest of our secular age. There has been so much talk about Peterson that it can be difficult to see through to the man himself and to know how to react if and when our teens become interested in the things he has to say. In this guide, we’ll get to know Jordan Peterson, as well as summarize and critique a few branches of his thinking from a Christian perspective. Our goal is to give you a deeper understanding of his thought, so that you can discuss him intelligently with your teenagers. We have based our judgments mainly on what he himself has said—no hearsay or partial commentary has been allowed in. Full disclosure up front: Overall, we think the guy is not a monster. -

Xenophobia: a New Pathology for a New South Africa?

Xenophobia: A new pathology for a new South Africa? by Bronwyn Harris In Hook, D. & Eagle, G. (eds) Psychopathology and Social Prejudice, pp. 169-184, Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 2002. Bronwyn Harris is a former Project Manager at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Introduction In 1994, South Africa became a new nation. Born out of democratic elections and inaugurated as the 'Rainbow Nation' by Nelson Mandela, this 'new South Africa' represents a fundamental shift in the social, political and geographical landscapes of the past. Unity has replaced segregation, equality has replaced legislated racism and democracy has replaced apartheid, at least in terms of the law. Despite the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, prejudice and violence continue to mark contemporary South Africa. Indeed, the shift in political power has brought about a range of new discriminatory practices and victims. One such victim is 'The Foreigner'. Emergent alongside a new-nation discourse, The Foreigner stands at a site where identity, racism and violent practice are reproduced. This paper interrogates the high levels of violence that are currently directed at foreigners, particularly African foreigners, in South Africa. It explores the term 'xenophobia' and various hypotheses about its causes. It also explores the ways in which xenophobia itself is depicted in the country. Portrayed as negative, abnormal and the antithesis of a healthy, normally functioning individual or society, xenophobia is read here as a new pathology for a 'new South Africa'. This chapter attempts to deconstruct such a representation by suggesting that xenophobia is implicit to the technologies of nation-building and is part of South Africa's culture of violence. -

When Is a Country Multinational? Problems with Statistical and Subjective Approaches

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2011 When is a country multinational? Problems with statistical and subjective approaches Stojanovic, N Abstract: Many authors have argued that we should make a clear conceptual distinction between monona- tional and multinational states. Yet the number of empirical examples they refer to is rather limited. France or Germany are usually seen as mononational, whereas Belgium, Canada, Spain and the UK are considered multinational. How should we classify other cases? Here we can distinguish between (at least) two approaches in the literature: statistical (i.e., whether significant national minorities live within a larger state and, especially, whether they claim self-government) and subjective (i.e., when citizens feel allegiance to sub-state national identities). Neither of them, however, helps us to resolve the problem. Is Italy multinational (because it contains a German-speaking minority)? Is Germany really mononational (in spite of the official recognition of the Danes and the Sorbs in some Länder)? On the otherhand, is Switzerland the “most multinational country” (Kymlicka)? Let us assume that there is no definite answer to this dilemma and that it is all a matter of degree. There are probably few (if any) clearly mononational states and few (if any) clearly multinational states. Should we abandon this distinction in favour of other concepts like “plurinationalism” (Keating), “nations-within-nations” (Miller), “post- national state” (Abizadeh, Habermas), or “post-sovereign state” (MacCormick)? The article discusses these issues and, in conclusion, addresses the problem of stability and shared identity “plural” societies. -

A Nation at Risk

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform A Report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education United States Department of Education by The National Commission on Excellence in Education April 1983 April 26, 1983 Honorable T. H. Bell Secretary of Education U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202 Dear Mr. Secretary: On August 26, 1981, you created the National Commission on Excellence in Education and directed it to present a report on the quality of education in America to you and to the American people by April of 1983. It has been my privilege to chair this endeavor and on behalf of the members of the Commission it is my pleasure to transmit this report, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. Our purpose has been to help define the problems afflicting American education and to provide solutions, not search for scapegoats. We addressed the main issues as we saw them, but have not attempted to treat the subordinate matters in any detail. We were forthright in our discussions and have been candid in our report regarding both the strengths and weaknesses of American education. The Commission deeply believes that the problems we have discerned in American education can be both understood and corrected if the people of our country, together with those who have public responsibility in the matter, care enough and are courageous enough to do what is required. Each member of the Commission appreciates your leadership in having asked this diverse group of persons to examine one of the central issues which will define our Nation's future. -

EXONYMS and OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia As an Exonym in Some Languages

57-1-Special issue_acta49-1.qxd 5.5.2017 9:31 Page 99 Acta geographica Slovenica, 57-1, 2017, 99–107 EXONYMS AND OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia as an exonym in some languages. Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac, Exonyms and other geographical names Exonyms and other geographical names DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/10.3986/AGS.4891 UDC: 91:81’373.21 COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: Geographical names are proper names of geographical features. They are characterized by different meanings, contexts, and history. Local names of geographical features (endonyms) may differ from the foreign names (exonyms) for the same feature. If a specific geographical name has been codi - fied or in any other way established by an authority of the area where this name is located, this name is a standardized geographical name. In order to establish solid common ground, geographical names have been coordinated at a global level by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) since 1959. It is assisted by twenty-four regional linguistic/geographical divisions. Among these is the East Central and South-East Europe Division, with seventeen member states. Currently, the divi - sion is chaired by Slovenia. Some of the participants in the last session prepared four research articles for this special thematic issue of Acta geographica Slovenica . All of them are also briefly presented in the end of this article. KEY WORDS: geographical name, endonym, exonym, UNGEGN, cultural heritage This article was submitted for publication on November 15 th , 2016. ADDRESSES: Drago Perko, Ph.D. -

Exonyms – Standards Or from the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4

NO. 50 JUNE 2016 In this issue Preface Message from the Chairperson 3 Exonyms – standards or From the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4 Special Feature – Exonyms – standards standardization? or standardization? What are the benefits of discerning 5-6 between endonym and exonym and what does this divide mean Use of Exonyms in National 6-7 Exonyms/Endonyms Standardization of Geographical Names in Ukraine Dealing with Exonyms in Croatia 8-9 History of Exonyms in Madagascar 9-11 Are there endonyms, exonyms or both? 12-15 The need for standardization Exonyms, Standards and 15-18 Standardization: New Directions Practice of Exonyms use in Egypt 19-24 Dealing with Exonyms in Slovenia 25-29 Exonyms Used for Country Names in the 29 Repubic of Korea Botswana – Exonyms – standards or 30 standardization? From the Divisions East Central and South-East Europe 32 Division Portuguese-speaking Division 33 From the Working Groups WG on Exonyms 31 WG on Evaluation and Implementation 34 From the Countries Burkina Faso 34-37 Brazil 38 Canada 38-42 Republic of Korea 42 Indonesia 43 Islamic Republic of Iran 44 Saudi Arabia 45-46 Sri Lanka 46-48 State of Palestine 48-50 Training and Eucation International Consortium of Universities 51 for Training in Geographical Names established Upcoming Meetings 52 UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 50 June 2106 Page 1 UNGEGN Information Bulletin The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat is served by the Statistics Division (UNSD), Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. -

The Centralia the Origin and the Basics

1 The Centralia The Origin and the Basics o see what China is and represents takes one to an ocean of information Tabout 20 percent of the humankind living on a continent over millennia. Appropriate to its mountainous volume, the existing knowledge of China is defiled by countless myths and distortions that often mislead even the most focused about China’s past, present, and future. Generations of students of China have translated and clarified much of the Chinese mystique. Many sturdy Chinese peculiarities, however, persist to impede standardization and general- ization of China studies that still critically need more historically grounded researches (Perry 1989, 579–91). To read the Chinese history holds a key to a proper understanding of China. Yet, the well-kept, rich, and massive Chi- nese historical records are particularly full of deliberate omissions, inadvertent inaccuracies, clever distortions, and blatant forgeries. A careful, holistic, and revisionist deciphering of the Chinese history, therefore, is the prerequisite to opening the black box of Chinese peculiarities. The first step is to clarify the factual fundamentals of China, the Centralia, that are often missed, miscon- strued, or misconceived. The revealed and rectified basics inform well the rich sources and the multiple origins of China as a world empire. This chapter thus explores the nomenclature, the ecogeography, the peoples, and the writing of history in the Chinese World. The starting point is the feudal society prior to the third century BCE, the pre-Qin Era when the Eastern Eurasian continent was under a Westphalia-like world order. The Chinese Nomenclature: More than Just Semantics China (Sina in Latin, Cīna in Sanskrit, and Chine in French) is most prob- ably the phonetic translation of a particular feudal state, later a kingdom in today’s Western China (䦎⚥ the Qin or the Chin, 770–221 BCE) that 9 © 2017 State University of New York Press, Albany 10 The China Order became an empire and united and ruled the bulk of East Asian continent (䦎㛅 221–207 BCE).