The Gods on the East Frieze of the Parthenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

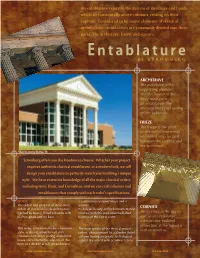

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Iconographical Studies on Nike in 5Th Century BC

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Visual & Performing Arts Faculty Publications Visual & Performing Arts Department 4-2003 Iconographical Studies on Nike in 5th Century B.C.: Investigations of Her Functions and Nature by Cornelia Thöne Katherine Schwab Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/visualandperformingarts- facultypubs Originally appears in American Journal of Archaeology. Copyright 2003 Archaeological Institute of America. Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Schwab, Katherine, "Iconographical Studies on Nike in 5th Century B.C.: Investigations of Her Functions and Nature by Cornelia Thöne" (2003). Visual & Performing Arts Faculty Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/visualandperformingarts-facultypubs/4 Published Citation Schwab, Katherine. 2003. Review of Iconographical Studies on Nike in 5th Century B.C.: Investigations of Her Functions and Nature, by Cornelia Thöne. AJA 107(2):310-311. This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 310 BOOK REVIEWS [AJA 107 In fact, much of the focus of this book is on material chaic period to the end of the fifth century B.C., from a that, for typological or geographical reasons, often re- more restricted and formulaic representation to one with ceives limited attention in handbooks. -

The Conversion of the Parthenon Into a Church: the Tübingen Theosophy

The Conversion of the Parthenon into a Church: The Tübingen Theosophy Cyril MANGO Δελτίον XAE 18 (1995), Περίοδος Δ'• Σελ. 201-203 ΑΘΗΝΑ 1995 Cyril Mango THE CONVERSION OF THE PARTHENON INTO A CHURCH: THE TÜBINGEN THEOSOPHY Iveaders of this journal do not have to be reminded of the sayings "of a certain Hystaspes, king of the Persians the uncertainty that surrounds the conversion of the or the Chaldaeans, a very pious man (as he claims) and for Parthenon into a Christian church. Surprisingly to our that reason deemed worthy of receiving a revelation of eyes, this symbolic event appears to have gone entirely divine mysteries concerning the Saviour's incarnation"5. unrecorded. The only piece of written evidence that has At the end of the work was placed a very brief chronicle been adduced concerns the removal of Athena's cult (perhaps simply a chronology) from Adam to the emperor statue, mentioned without a firm date in Marinus' Life of Zeno (474-91), in which the author advanced the view that Proclus (written in 485/6, the year following the the world would end in the year 6000 from Creation. philosopher's death)1. It is not clear, however, whether The original work was, therefore, composed between this removal marked the conversion of the building to 474 and, at the latest, 508, assuming the author was using Christian worship or merely its desacralization. The two, the Alexandrian computation from 5492 BC. The we have been told, need not have been simultaneous and expectation that the world would end in the reign of it is not inconceivable that the Parthenon remained Anastasius was, indeed, quite widespread at the time6. -

The Victory of Kallimachos Harrison, Evelyn B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1971; 12, 1; Proquest Pg

The Victory of Kallimachos Harrison, Evelyn B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1971; 12, 1; ProQuest pg. 5 The Victory of Kallimachos Evelyn B. Harrison HE FRAGMENTARY EPIGRAM from the Athenian Acropolis! record Ting a dedication to Athena by Kallimachos of Aphidna and apparently referring to his service at Marathon has been dis cussed and tentatively restored in various ways, but no complete restoration has found general agreement. Meiggs and Lewis, in A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions nO.18, print a conservative text, restoring only the first two verses completely and quoting in foot notes the supplements of Shefton and Ed. Fraenkel for the last three verses.2 Raubitschek, in a general discussion of Greek inscriptions as historical documents, also prints a text without the most controver sial restorations.3 Both still accept, however, the restoration which refers to the offering as "messenger of the immortals" and believe that the column on which the inscription was carved supported one of the winged female figures of which several examples have been lIG 12 609. Most recently, R. Meiggs and D. M. Lewis, A Selection of Greek Historical In scriptions (Oxford 1969). Add to their bibliography A. E. Raubitschek, Gymnasium 72 (1965) 512. The long article by B. B. Shefton, BSA 45 (1950) 14D--64, is the most informative about the stone, since it includes photographs and full discussion of difficult letters as well as a great deal of background material. 1 am grateful to Ronald Stroud for making me a good squeeze of the inscription and to Helen Besi for the drawings, unusually difficult to make because of the concave surface in which the letters are engraved. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Download Notes 10-04.Pdf

Can you kill a god? Can he feel pain? Can you make him bleed? What do gods eat? Does Zeus delegate authority? Why does Zeus get together with Hera? Which gods are really the children of Zeus and Hera? Anthropomorphic Egyptian Greek ἡ ἀμβροσία ambrosia τὸ νέκταρ nectar ὁ ἰχώρ ichor Games and Traditions epichoric = local tradition Panhellenic = common, shared tradition Dumézil’s Three Functions of Indo-European Society (actually Plato’s three parts of the soul) religion priests τὀ λογιστικόν sovereignty 1 kings (reason) justice τὸ θυμοειδές warriors military 2 (spirit, temper) craftsmen, production τὸ ἐπιθυμητικόν farmers, economy 3 (desire, appetite) herders fertility Gaia Uranus Iapetus X Cœus Phœbe Rhea Cronos Atlas Pleione Leto gods (next slide) Maia Rhea Cronos Aphrodite? Hestia Hades Demeter Poseidon Hera Zeus Ares (et al.) Maia Leto Hephæstus Hermes Apollo Artemis Athena ZEUS Heaven POSEIDON Sea HADES Underworld ἡ Ἐστία HESTIA Latin: Vesta ἡ Ἥρα HERA Latin: Juno Boōpis Cuckoo Cow-Eyed (Peacock?) Scepter, Throne Argos, Samos Samos (Heraion) Argos Heraion, Samos Not the Best Marriage the poor, shivering cuckoo the golden apples of the Hesperides (the Daughters of Evening) honeymoon Temenos’ three names for Hera Daidala Athena Iris Hera Milky Way Galaxy Heracles Hera = Zeus Hephæstus Ares Eris? Hebe Eileithyia ὁ Ζεύς, τοῦ Διός ZEUS Latin: Juppiter Aegis-bearer Eagle Cloud-gatherer Lightning Bolt Olympia, Dodona ἡ ξενία xenia hospitality ὁ ὅρκος horcus ἡ δίκη oath dicē justice Dodona Olympia Crete Dodona: Gaia, Rhea, Dione, Zeus Olympia: -

ENGLISH HOME LANGUAGE GRADE 9 Reading a Myth: Persephone

ENGLISH HOME LANGUAGE GRADE 9 Reading a myth: Persephone MEMORANDUM 1. This myth explains the changing of the seasons. Which season is your favourite and why? Learners own response. Winter/Autumn/Spring/Summer✓ + reason.✓ 2. Myths are stories that explain natural occurrences and express beliefs about what is right and wrong. What natural occurrence does the bracketed paragraph explain? The paragraph relates to earthquakes and volcanos✓ that shake the earth’s core. It suggests that “fearful’ fire-breathing giants” presumably volcanos✓, heave and struggle to get free, which causes the earthquakes. ✓ 3. How do the Greeks explain how people fall in love? Eros (Cupid) the god of love✓, shoots people in the heart with a love-arrow✓ that makes them fall in love. 4. Who is Pluto? He is the “dark monarch” king of the underworld✓ otherwise known as hell. 5. A cause is an effect or action that produces a result. A result is called an effect. What effect does Eros’s arrow have on Pluto? Eros’s arrow fills Pluto’s heart with warm emotions. ✓He sees Persephone and immediately falls in love with her. ✓ 6. What is the result of Demeter’s anger at the land? The ground was no longer fertile. ✓ Nothing could grow anymore. Men and oxen worked to grow crops, but they could not. ✓ There was too much rain ✓ and too much sun✓, so the crops did not grow. The cattle died✓ due to starvation. All of mankind would die✓ of starvation. 7. How do the details that describe what happened to the earth explain natural occurrences? The paragraph suggests that drought✓ is caused by Demeter who is angry✓ with the land. -

Nagy Commentary on Euripides, Herakles

Informal Commentary on Euripides, Herakles by Gregory Nagy 97 The idea of returning from Hades implies a return from death 109f The mourning swan... Cf. the theme of the swansong. Cf. 692ff. 113 “The phantom of a dream”: cf. skias onar in Pindar Pythian 8. 131f “their father’s spirit flashing from their eyes”: beautiful rendition! 145f Herakles’ hoped-for return from Hades is equated with a return from death, with resurrection; see 297, where this theme becomes even more overt; also 427ff. 150 Herakles as the aristos man: not that he is regularly described in this drama as the best of all humans, not only of the “Greeks” (also at 183, 209). See also the note on 1306. 160 The description of the bow as “a coward’s weapon” is relevant to the Odysseus theme in the Odyssey 203 sôzein to sôma ‘save the body’... This expression seems traditional: if so, it may support the argument of some linguists that sôma ‘body’ is derived from sôzô ‘save’. By metonymy, the process of saving may extend to the organism that is destined to be saved. 270 The use of kleos in the wording of the chorus seems to refer to the name of Herakles; similarly in the wording of Megara at 288 and 290. Compare the notes on 1334 and 1369. 297 See at 145f above. Cf. the theme of Herakles’ wrestling with Thanatos in Euripides Alcestis. 342ff Note the god-hero antagonism as expressed by Amphitryon. His claim that he was superior to Zeus in aretê brings out the meaning of ‘striving’ in aretê (as a nomen actionis derived from arnumai; cf. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Greek Culture

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE GREEK CULTURE Course Description Greek Culture explores the culture of ancient Greece, with an emphasis on art, economics, political science, social customs, community organization, religion, and philosophy. About the Professor This course was developed by Frederick Will, Ph.D., professor emeritus from the University of Iowa. © 2015 by Humanities Institute Course Contents Week 1 Introduction TEMPLES AND THEIR ART Week 2 The Greek Temple Week 3 Greek Sculpture Week 4 Greek Pottery THE GREEK STATE Week 5 The Polis Week 6 Participation in the Polis Week 7 Economy and Society in the Polis PRIVATE LIFE Week 8 At the Dinner Table Week 9 Sex and Marriage Week 10 Clothing CAREERS AND TRAINING Week 11 Farmers and Athletes Week 12 Paideia RELIGION Week 13 The Olympian Gods Week 14 Worship of the Gods Week 15 Religious Scepticism and Criticism OVERVIEW OF GREEK CULTURE Week 16 Overview of Greek Culture Selected collateral readings Week 1 Introduction Greek culture. There is Greek literature, which is the fine art of Greek culture in language. There is Greek history, which is the study of the development of the Greek political and social world through time. Squeezed in between them, marked by each of its neighbors, is Greek culture, an expression, and little more, to indicate ‘the way a people lived,’ their life- style. As you will see, in the following syllabus, the ‘manner of life’ can indeed include the ‘products of the finer arts’—literature, philosophy, by which a people orients itself in its larger meanings—and the ‘manner of life’ can also be understood in terms of the chronological history of a people; but on the whole, and for our purposes here, ‘manner of life’ will tend to mean the way a people builds a society, arranges its eating and drinking habits, builds its places of worship, dispenses its value and ownership codes in terms of an economy, and arranges the ceremonies of marriage burial and social initiation. -

A „Szőke Tisza” Megmentésének Lehetőségei

A „SZŐKE TISZA” MEGMENTÉSÉNEK LEHETŐSÉGEI Tájékoztató Szentistványi Istvánnak, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnökének Összeállította: Dr. Balogh Tamás © 2012.03.27. TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület 2 TÁJÉKOZTATÓ Szentistványi István, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke részére a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban 2012. március 27-én Szentistványi István a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke e-mailben kért tájékoztatást Dr. Balogh Tamástól a TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület elnökétől a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban, hogy tájékozódjon a hajó megmentésének lehetőségéről – „akár jelentősebb anyagi ráfordítással, esetleges városi összefogással is”. A megkeresésre az alábbi tájékoztatást adom: A hajó 2012. február 26-án süllyedt el. Azt követően egyesületünk honlapján – egy a hajónak szentelt tematikus aloldalon – rendszeresen tettük közzé a hajóra és a mentésére vonatkozó információkat, képeket, videókat (http://hajosnep.hu/#!/lapok/lap/szoke-tisza-karmentes), amelyekből szinte napi ütemezésben nyomon követhetők a február 26-március 18 között történt események. A honlapon elérhető információkat nem kívánom itt megismételni. Egyebekben a hajó jelentőségéről és az esetleges városi véleménynyilvánítás elősegítésére az alábbiakat tartom szükségesnek kiemelni: I) A hajó jelentősége: Bár a Kulturális Örökségvédelmi Hivatal előtt jelenleg zajlik a hajó örökségi védelembe vételére irányuló eljárás (a hajó örökségi -

Ancient Egyptian Dieties

Ancient Egyptian Dieties Amun: When Amun’s city, Thebes, rose to power in the New Kingdom (1539-1070 B.C.), Amun became known as the “King of the Gods.” He was worshipped as the high god throughout Egypt. Able to take many shapes, Amun was sometimes shown as a ram or goose, but was usually shown in human form. He is fundamentally a Creator God and his name, Amun, means “The Hidden One.” Amun-Re: Originating in the Middle Kingdom, (2055 - 1650 B.C.), Amun-Re is a fusion of the Gods Amun and Re. He combined the invisible power of creation and the power visible in heat and light. Anubis: Usually represented as a black jackal, or as a human with a canine head, Anubis was a guardian of mummies, tombs, and cemeteries, as well as an escort of the deceased to the afterlife. Atum: According to the most ancient Egyptian creation myths, Atum is the creator of the world. He also brought the first gods Shu (air), Tefnut (water), Geb (earth), and Nut (sky) to Egypt. He is also god of the setting sun. Atum was represented in many forms such as a human, a human with the head of a ram, and a combination of an eel and a cobra. Bastet: Originating as early as Dynasty II (2820-2670 B.C.), Bastet was represented as a cat or a woman with a lioness’s head. She eventually became Egypt’s most important “cat goddess.” If Bastet took the form of a cat she was considered content, but if Bastet was a lioness she was considered an angry goddess.