Alexander Marius Jacob of Political Awareness—Beggars’ Revolts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

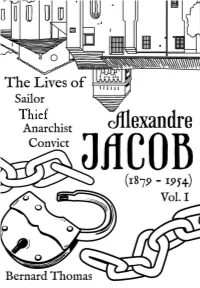

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

The Brief Summer of Anarchy: the Life and Death of Durruti - Hans Magnus Enzensberger

The Brief Summer of Anarchy: The Life and Death of Durruti - Hans Magnus Enzensberger Introduction: Funerals The coffin arrived in Barcelona late at night. It rained all day, and the cars in the funeral cortege were covered with mud. The black and red flag that draped the hearse was also filthy. At the anarchist headquarters, which had been the headquarters of the employers association before the war,1 preparations had already been underway since the previous day. The lobby had been transformed into a funeral chapel. Somehow, as if by magic, everything was finished in time. The decorations were simple, without pomp or artistic flourishes. Red and black tapestries covered the walls, a red and black canopy surmounted the coffin, and there were a few candelabras, and some flowers and wreaths: that was all. Over the side doors, through which the crowd of mourners would have to pass, signs were inscribed, in accordance with Spanish tradition, in bold letters reading: “Durruti bids you to enter”; and “Durruti bids you to leave”. A handful of militiamen guarded the coffin, with their rifles at rest. Then, the men who had accompanied the coffin from Madrid carried it to the anarchist headquarters. No one even thought about the fact that they would have to enlarge the doorway of the building for the coffin to be brought into the lobby, and the coffin-bearers had to squeeze through a narrow side door. It took some effort to clear a path through the crowd that had gathered in front of the building. From the galleries of the lobby, which had not been decorated, a few sightseers watched. -

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

Unforgiving Years by Victor Serge (Translated from the French and with an Introduction by Richard Greeman), NYRB Classics, 2008, 368 Pp

Unforgiving Years by Victor Serge (Translated from the French and with an introduction by Richard Greeman), NYRB Classics, 2008, 368 pp. Michael Weiss In the course of reviewing the memoirs of N.N. Sukhanov – the man who famously called Stalin a ‘gray blur’ – Dwight Macdonald gave a serviceable description of the two types of radical witnesses to the Russian Revolution: ‘Trotsky’s is a bird’s- eye view – a revolutionary eagle soaring on the wings of Marx and History – but Sukhanov gives us a series of close-ups, hopping about St. Petersburg like an earth- bound sparrow – curious, intimate, sharp-eyed.’ If one were to genetically fuse these two avian observers into one that took flight slightly after the Bolshevik seizure of power, the result would be Victor Serge. Macdonald knew quite well who Serge was; the New York Trotskyist and scabrous polemicist of Partisan Review was responsible, along with the surviving members of the anarchist POUM faction of the Spanish Civil War, for getting him out of Marseille in 1939, just as the Nazis were closing in and anti-Stalinist dissidents were escaping the charnel houses of Eurasia – or not escaping them, as was more often the case. Macdonald, much to his later chagrin, titled his own reflections on his youthful agitations and indiscretions Memoirs of a Revolutionist, an honourable if slightly wince-making tribute to Serge, who earned every syllable in his title, Memoirs of a Revolutionary. And after the dropping of both atomic bombs on Japan, it was Macdonald’s faith in socialism that began to -

TAZ, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.Pdf

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America Part 1 T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many--sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok); Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic (Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Louise Michel

also published in the rebel lives series: Helen Keller, edited by John Davis Haydee Santamaria, edited by Betsy Maclean Albert Einstein, edited by Jim Green Sacco & Vanzetti, edited by John Davis forthcoming in the rebel lives series: Ho Chi Minh, edited by Alexandra Keeble Chris Hani, edited by Thenjiwe Mtintso rebe I lives, a fresh new series of inexpensive, accessible and provoca tive books unearthing the rebel histories of some familiar figures and introducing some lesser-known rebels rebel lives, selections of writings by and about remarkable women and men whose radicalism has been concealed or forgotten. Edited and introduced by activists and researchers around the world, the series presents stirring accounts of race, class and gender rebellion rebel lives does not seek to canonize its subjects as perfect political models, visionaries or martyrs, but to make available the ideas and stories of imperfect revolutionary human beings to a new generation of readers and aspiring rebels louise michel edited by Nic Maclellan l\1Ocean Press reb� Melbourne. New York www.oceanbooks.com.au Cover design by Sean Walsh and Meaghan Barbuto Copyright © 2004 Ocean Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 1-876175-76-1 Library of Congress Control No: 2004100834 First Printed in 2004 Published by Ocean Press Australia: GPO Box 3279, -

Historia De La

La Historia de la FAI de Juan Gómez Casas, constituye una aproximación a la historia de la Federación Anarquista Ibérica, desde su fundación hasta el final de la guerra civil, arrancando desde la historia anterior del anarquismo para comprender mejor la actuación de esta organización. Si bien la FAI se crea como una entidad de propaganda de las ideas anarquistas, la lucha de clases de aquella época en España -Segunda República y guerra civil- hace de ella una organización en la que la acción militante juega un papel de primera magnitud. Juan Gómez Casas HISTORIA DE LA FAI Aproximación a la historia de la organización específica del anarquismo ibérico y sus antecedentes de la Alianza de la Democracia Socialista. Editado por la Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo, las distribuidoras Sur Libertario y La Idea y los grupos anarquistas Tierra y Albatros Edición digital: C. Carretero Difunde: Confederación Sindical Solidaridad Obrera http://www.solidaridadobrera.org/ateneo_nacho/biblioteca.html Contenido Agradecimientos Prólogo I. Antecedentes de la alianza de la democracia socialista en España II. La CNT y el anarquismo hasta la dictadura de Primo de Rivera III. Anarquismo y anarcosindicalismo en la dictadura de Primo de Rivera y hasta el advenimiento de la Segunda República IV. La Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) V. La Guerra Civil. La trabazón CNT-FAI Acerca del autor Agradezco en estas líneas la ayuda que han representado para mí los pacientes trabajos con que respondieron a mi encuesta diversos amigos, entre los que cito a José Peirats, Marcos Alcón, Abad de Santillán y Tomás y Benjamín Cano Ruíz. También se prestaron cordialmente a responder a algunas de mis preguntas y aportaron datos esclarecedores Juan García Oliver, Juan Manuel Molina y Antonio Moreno Toledano. -

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti: a Global History

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti: A Global History Lisa McGirr On May 1, 1927, in the port city of Tampico, Mexico, a thousand workers gathered at the American consulate. Blocking the street in front of the building, they listened as lo- cal union officials and radicals took turns stepping onto a tin garbage can to shout fiery speeches. Their denunciations of American imperialism, the power of Wall Street, and the injustices of capital drew cheers from the gathered crowd. But it was their remarks about the fate of two Italian anarchists in the United States, Nicola Sacco and Bartolo- meo Vanzetti, that aroused the "greatest enthusiasm," in the words of an American consular official who observed the event. The speakers called Sacco and Vanzetti their "compatriots" and "their brothers." They urged American officials to heed the voice of "labor the world over" and release the men from their deatb sentences.' Between 1921 and 1927, as Sacco and Vanzetti's trial and appeals progressed, scenes like the one in Tampico were replayed again and again throughout latin America and Europe. Over those six years, the Sacco and Vanzetti case developed from a local robbery and mur- der trial into a global event. Building on earlier networks, .solidarities, and identities and impelled forward by a short-lived but powerful sense of transnational worker solidarity, the movement in the men's favor crystallized in a unique moment of international collective mobilization. Although the world would never again witness an international, worker-led protest of comparable scope, the movement to save Sacco and Vanzetti highlighted the ever- denser transnational networks that continued to shape social movements throughout the twentieth century.' The "travesty of justice" protested by Mexican, French, Argentine, Australian, and Ger- man workers, among others, originated in events that took place just outside Boston in 1920. -

2015-08-06 *** ISBD LIJST *** Pagina 1 ______Monografie Ni Dieu Ni Maître : Anthologie De L'anarchisme / Daniel Guérin

________________________________________________________________________________ 2015-08-06 *** ISBD LIJST *** Pagina 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ monografie Ni Dieu ni Maître : anthologie de l'anarchisme / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1973-1976 monografie Vol. 4: Dl.4: Makhno ; Cronstadt ; Les anarchistes russes en prison ; L'anarchisme dans la guerre d'Espagne / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1973. - 196 p. monografie Vol. 3: Dl.3: Malatesta ; Emile Henry ; Les anarchistes français dans les syndicats ; Les collectivités espagnoles ; Voline / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1976. - 157 p. monografie De Mechelse anarchisten (1893-1914) in het kader van de opkomst van het socialisme / Dirk Wouters. - [S.l.] : Dirk Wouters, 1981. - 144 p. meerdelige publicatie Hem Day - Marcel Dieu : een leven in dienst van het anarchisme en het pacifisme; een politieke biografie van de periode 1902-1940 / Raoul Van der Borght. - Brussel : Raoul Van der Borght, 1973. - 2 dl. (ongenummerd) Licentiaatsverhandeling VUB. - Met algemene bibliografie van Hem Day Bestaat uit 2 delen monografie De vervloekte staat : anarchisme in Frankrijk, Nederland en België 1890-1914 / Jan Moulaert. - Berchem : EPO, 1981. - 208 p. : ill. Archief Wouter Dambre monografie The floodgates of anarchy / Stuart Christie, Albert Meltzer. - London : Sphere books, 1972. - 160 p. monografie L' anarchisme : de la doctrine à l'action / Daniel Guerin. - Paris : Gallimard, 1965. - 192 p. - (Idées) Bibliotheek Maurice Vande Steen monografie Het sociaal-anarchisme / Alexander Berkman. - Amsterdam : Vereniging Anarchistische uitgeverij, 1935. - 292 p. : ill. monografie Anarchism and other essays / Emma Goldman ; introduction Richard Drinnon. - New York : Dover Public., [1969?]. - 271 p. monografie Leven in de anarchie / Luc Vanheerentals. - Leuven : Luc Vanheerentals, 1981. - 187 p. monografie Kunst en anarchie / met bijdragen van Wim Van Dooren, Machteld Bakker, Herbert Marcuse. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination.