The Anarchist Question René Furth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

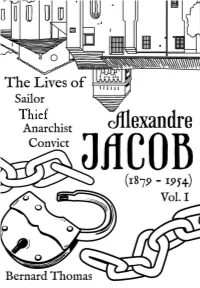

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

Richard Parry

by Richard Parry THE BONNOT GANG The story of the French illegalists Other Rebel Press titles: Dynamite: A century of class violence in America, Louis Adamic Ego and its Own, The, Max Stirner On the Poverty of Student Life Paris: May 1968 Quiet Rumours, various Revolution of Everyday Life , The, Raoul Vaneigem Untying the Knot, Freeman and Levine THE BON NOT GANG by Richard Parry REBEL PRESS, 1987 Published by Rebel Press in 1987 © Richard Parry, 1986 Photographic work by Matthew Parry and Herve Brix ISBN 0 946061 04 1 Printed and typeset by Aldgate Press 84b Whitechapel High Street, London El 7QX Contents Preface5 One From illegality to illegalism Making virtue of necessity9 ii Saint Max15 Two A new beginning Libertad21 ii City of thieves28 iii State of emergency 30 Three The rebels i· Brussels33 ii Paris42 III Blood on the streets 44 iv Strike! 45 Four Anarchy in suburbia The move47 ii The Romainville commune 51 iii' Collapse of the Romainville commune 57 iv Paris again60 Five Bonnot I The 'Little Corporal' 64 ii In search of work65 III The illegalist66 IV Accidental death of an anarchist70 Six The gang forms A meeting of egoists 73 11 Science on the side of the Proletariat75 iii Looking for a target 76 Seven The birth of tragedy I The first ever hold-up by car 80 ii Crimedoesn't pay84 111 Jeux sans frontieres 88 iv Victor's dilemma89 Eight Kings of the road i Drivin' South 94 ii The left hand of darkness 97 iii Stalemate 99 Nine Calm before the storm 1 'Simentoff' 103 ii Of human bondage 104 iii Dieudonne in the hot seat 108 iv Garnier's challenge 109 Ten Kings of the road (part two) 1 Attack 113 ii State of siege 117 Eleven The Suretefights back To catch an anarchist 120 11 Hide and seek 123 iii Exit Jouin 126 Twelve Twilight of the idols The wrath of Guichard 129 11 Shoot-out at 'The Red Nest' 133 iii Obituaries 137 iv To the Nogent station 139 v The last battle 142 Thirteen In the belly of the beast 1 Limbo 147 ii Judgement 152 iii Execution 159 Fourteen The end of anarchism? 166 Epilogue 175 Map of Paris c. -

The Penal Colony of French Guiana

The French Empire, 1542–1976 Jean-Lucien Sanchez To cite this version: Jean-Lucien Sanchez. The French Empire, 1542–1976. Clare Anderson. A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies , Bloomsbury, 2018. hal-01813392 HAL Id: hal-01813392 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01813392 Submitted on 12 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The French Empire, 1542–1976 Jean-Lucien Sanchez Introduction From 1852 to 1953 more than 100,000 convicts (bagnards or forçats) from France and the French colonial empire were sent to penal colonies (colonies pénitentiaires or bagnes coloniaux) located in French Guiana and New Caledonia. Inspired by the penal colonization model set up by Great Britain in Australia,1 the French legislature of the Second Empire wanted to use convicted offenders to expand the empire while contributing to the enrichment of the metropolis. The goal was threefold: to empty the port prisons (bagnes portuaires) of Brest, Toulon and Rochefort of their convicts and expel them from the metropolis while simultaneously granting the colonies an abundant workforce; to promote colonial development; and to allow more deserving convicts to become settlers.2 Ten years after penal transportation to Australia had begun to slow (and was finally ended in 1868), France undertook a project that would continue for an entire century. -

Anarchism : a History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements

Anarchism : A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements GEORGE WOODCOCK Meridian Books The World Publishing Company Cleveland and New York -3- AN ORIGINAL MERIDIAN BOOK Published by The World Publishing Company 2231 West 110th Street, Cleveland 2, Ohio First printing March 1962 CP362 Copyright © 1962 by The World Publishing Company All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-12355 Printed in the United States of America -4- AN ORIGINAL MERIDIAN BOOK Published by The World Publishing Company 2231 West 110th Street, Cleveland 2, Ohio First printing March 1962 CP362 Copyright © 1962 by The World Publishing Company All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-12355 Printed in the United States of America -4- Contents 1. PROLOGUE 9 I. The Idea 2. THE FAMILY TREE 37 3. THE MAN OF REASON 60 4. THE EGOIST 94 5. THE MAN OF PARADOX 106 6. THE DESTRUCTIVE URGE 145 7. THE EXPLORER 184 8. THE PROPHET 222 II. The Movement 9. INTERNATIONAL ENDEAVORS 239 10. ANARCHISM IN FRANCE 275 11. ANARCHISM IN ITALY 327 12. ANARCHISM IN SPAIN 356 -5- 13. ANARCHISM IN RUSSIA 399 14. VARIOUS TRADITIONS: ANARCHISM IN LATIN AMERICA, NORTHERN EUROPE, BRITAIN, AND THE UNITED STATES 425 15. EPILOGUE 468 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 491 -6- Anarchism A HISTORY OF LIBERTARIAN IDEAS AND MOVEMENTS -7- [This page intentionally left blank.] -8- I. Prologue "Whoever denies authority and fights against it is an anarchist," said Sébastien Faure. The definition is tempting in its simplicity, but simplicity is the first thing to guard against in writing a history of anarchism. -

The Extremes of French Anarchism Disruptive Elements

Disruptive Elements The Extremes of French Anarchism Disruptive Elements Ardent Press Disruptive Elements This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License. https://creativecommons.org Ardent Press, 2014 Table of Contents Translator's Introduction — vincent stone i Bonjour — Le Voyeur ii The Philosophy of Defiance — Felix P. viii section 1 Ernest Coeurderoy (1825-1862) 1 Hurrah!!! or Revolution by the Cossacks (excerpts) 2 Citizen of the World 8 Hurrah!!! Or the Revolution by the Cossacks (excerpt) 11 section 2 Joseph Déjacque (1821-1864) 12 The Revolutionary Question 15 Le Libertaire 17 Scandal 19 The Servile War 21 section 3 Zo d’Axa (1864-1930) 25 Zo d’Axa, Pamphleteer and Libertarian Journalist — Charles Jacquier 28 Any Opportunity 31 On the Street 34 section 4 Georges Darien (1862 – 1921) 36 Le Voleur (excerpts) 40 Enemy of the People 44 Bon Mots 48 The Road to Individualism 49 section 5 Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917) 50 Ravachol 54 Murder Foul and Murder Fair 56 Voters Strike! 57 Moribund Society and Anarchy 60 Octave Mirbeau Obituary 62 section 6 Émile Pouget (1869 - 1931) 64 Boss Assassin 66 In the Meantime, Let’s Castrate Those Frocks! 68 Revolutionary Bread 70 section 7 Albert Libertad (1875-1908) 72 Albert Libertad — anonymous 74 The Patriotic Herd 75 The Greater of Two Thieves 76 To Our Friends Who Stop 78 Individualism 79 To the Resigned 83 Albert Libertad — M.N. 85 section 8 illegalism 88 The “Illegalists” — Doug Imrie 89 An Anarchist on Devil’s Island — Paul Albert 92 Expropriation and the Right to Live — Clement Duval 97 Obituary: Clement Duval — Jules Scarceriaux 99 Why I Became a Burglar — Marius Jacob 101 The Paris Auto-Bandits (The “Bonnot Gang”) — anonymous 104 “Why I Took Part in a Burglary, Why I Committed Murder” — Raymond Callemin 105 Is the Anarchist Illegalist Our Comrade? — É. -

Osvaldo Bayer Is Dead

Number 97-98 £1 or $2 Feb. 2019 Osvaldo Bayer is Dead One of Argentina’s most highly respected intellectuals, His activism led to his being targeted by the Triple the journalist and historian Osvaldo Bayer has died. A (Argentinean Anti-Communist Alliance) during the His revisionist approach to labour’s struggles and the government of Maria Estela Martínez de Perón and in repression of the organized workers introduced a 1975 he left for exile in Berlin. Some of his books car- watershed into the interpretation of Argentina’s his- ried titles such as The Anarchist Expropriators, tory. The slaughter of the peons, featured in his invest- Severino Di Giovanni: Violent Idealist, Argentinian igation Rebellion in Patagonia, maybe his best-known Football, Rebellion and Hope. He also wrote the book. For that and for other research cataloguing the screenplay for La Patagonia Rebelde, the movie direc- repression enforced by Argentina’s ruling classes and ted by Héctor Olivera exposing the massacre of patrician families, he was censured, harassed and Patagonian peasant labourers. threatened. He was forced into exile and was one of In 2008 he wrote the screenplay and illustrated book the voices outside the country denouncing the state published by Pagina/12. Called Awka Liwen and co- repression of the most recent civilian-military dictator- produced with Mariano Aiello and Kristina Hille, it ship. Upon coming home in the 1980s, he stood by his reported on the confiscation of the lands of native and beliefs. He published his articles in Pagina/12. He peasant communities and on the destruction of the showed up at every protest by workers, peasants and soil. -

LIBERTAD Selected Writings of Individualist Anarchy UNTORELLI PRESS “Freedom” and “We Go On” Taken from the Killing King Abacus Site

One comrade said of him that he was a one- man demonstration, a latent riot. His style of propaganda was summed up by Victor Serge as follows: “Don’t wait for the revo- lution. Those who promise revolution are frauds just like the others. Make your own revolution by being free men and living in comradeship.” His absolute commandment and rule of life was, “Let the old world go to blazes!” He had children to whom he refused to give state registration. “The State? Don’t know it. The name? I don’t give a damn, they’ll pick one that suits them. The law? To the devil with it!” He sung the praises of anarchy as a liberating force, which people could find inside themselves. LIBERTAD selected writings of individualist anarchy UNTORELLI PRESS “Freedom” and “We Go On” taken from the Killing King Abacus site. “Obsession” from Le Libertaire, August 26, 1898. “The Joy of Life” taken from Historical Anar- chist Texts. “Germinal, at the Wall of the Fédérés” from Le Droit de Vivre, no. 7, June 1–7, 1898. “To the Resigned” from l’anarchie, April 13, 1905. “May Day” from l’anar- chie, May 4, 1905. “To the Electoral Cattle” written February 1906. “Fear” from l’an- archie, May 17, 1906. “Down with the Law” from l’anarchie, February 15, 1906. “Weak Meat” written August 2, 1906. “The Cult of Carrion” from a pamphlet published in 1925, taken from articles that originally appeared in l’anarchie. “The Patriotic Herd” from l’anarchie, October 26, 1905. “The Greater of Two Thieves” from Germinal, no. -

HEALTH IS in YOU! Archive Ask Submit Some Suggested Titles Anarchist Histories Documenting the Illegal, the Attentat and Propagandas by the Deed

HEALTH IS IN YOU! Archive Ask Submit Some Suggested Titles Anarchist histories documenting the illegal, the attentat and propagandas by the deed. Courage comrades! Long live anarchy! Search this tumblelog. GREYING BY GABRIELLE WEE. POWERED BY TUMBLR. Sacco and Vanzetti both stood their second trial in Dedham, Massachusetts for the South Braintree robbery and murders, with Judge Webster Thayer again presiding; he had asked to be assigned the trial. Anticipating a possible bomb attack, authorities had the Dedham courtroom outfitted with cast-iron shutters, painted to appear wooden, and heavy, sliding steel doors. Each day during the trial, the courthouse was placed under heavy police security, and Sacco and Vanzetti were escorted in and out of the courtroom by armed guards. #sacco and vanzetti #anarchist #anarchists #anarchist history #galleanists #propaganda by the deed ∞ AUGUST 19, 2014 18 NOTES historicaltimes: Mugshot of anarchist Emma Goldman from when she was implicated in the assassination of President McKinley, 1901. ∞ AUGUST 19, 2014 192 NOTES VIA HISTORICALTIMES Never miss a post! × health-is-in-you Follow HEALTH IS IN YOU! HEALTH IS IN YOU! Archive Ask Submit Some Suggested Titles Anarchist histories documenting the illegal, the attentat and propagandas by the deed. Courage comrades! Long live anarchy! Search this tumblelog. GREYING BY GABRIELLE WEE. POWERED BY TUMBLR. historicaltimes: 1906: An Anarchist’s bomb explodes amidst Spanish King Alfonso XIII’s retinue. Several bystanders and horses are killed, the King is unharmed, and the Queen gets some spots of blood on her dress. ∞ AUGUST 19, 2014 194 NOTES VIA HISTORICALTIMES aflameoffreedom: Members of Chernoe Znamia (Чёрное знамя or Black Banner in English), a Russian anarchist group formed in the early 1900s around the time of the First Russian Revolution. -

Alexander Marius Jacob Alias Escande, Alias Attila, Alias Georges, Alias Bonnet, Alias Feran, Alias Hard to Kill, Alias the Burglar

Alexander Marius Jacob Alias Escande, alias Attila, alias Georges, alias Bonnet, alias Feran, alias Hard to Kill, alias The Burglar Bernard Thomas 1970 Contents Introduction ......................................... 3 The Bandits 7 The Agitator 19 I ................................................ 19 II ................................................ 27 III ............................................... 43 IV ............................................... 52 The Hundred and Fifty ‘Crimes’ of the Other Arsène Lupin 64 I ................................................ 64 II ................................................ 79 III ............................................... 98 IV ............................................... 109 V ................................................ 117 A Quarter of a Century on Devil’s Island 137 I ................................................ 137 II ................................................ 150 III ............................................... 169 The Quiet Family Man 178 Some Bibliography ...................................... 188 Newspapers ...................................... 188 On the penal colony .................................. 188 On anarchy ....................................... 189 Various ......................................... 189 2 Introduction Rigor and precision have finally disappeared from the field of human procrastination. With the recognition that a strictly organisational perspective is not enough to solve the dilemma of ‘what is to be done’, the need for order -

Abbasso Le Prigioni, Tutte Le Prigioni! Di Alexandre Marius Jacob a Cura Di Andrea Ferreri Jacob L’Anarchico Di Andrea Ferreri

Abbasso le prigioni, tutte le prigioni! di Alexandre Marius Jacob a cura di Andrea Ferreri Jacob l’anarchico di Andrea Ferreri “Il diritto di vivere non si mendica, si prende.” Alexandre Marius Jacob Nell’immaginario della società contemporanea la figura del ladro è stata associata quasi esclusivamente al crimine e più specificamente al reato di “appropriazione indebita”. Il ladro è l’usurpatore di beni che non gli appartengono, colui che contro la legge sottrae un bene mobile in danno del suo legittimo proprietario. Ma non è stato sempre o necessariamente così, almeno non per Alexandre Jacob, l’anarchico francese che ha fatto del furto uno strumento per dare dignità a tutti coloro che la società dell’opulenza aveva negato, mettendoli al margine e privandoli dei mezzi per il semplice sostentamento, riducendoli alla miseria e “derubandoli” secondo Jacob stesso. Alexandre Marius Jacob nasce a Marsiglia nel settembre del 1879 da una famiglia umile, il padre marinaio di professione li trasmette da subito la passione per i viaggi e le avventure, a 11 anni si imbarca come mozzo sul bastimento Thibet, a 13 si ritrova in Australia dove impara l’inglese e per fame anche a rubare. Qualche anno dopo parte da Sidney con una baleniera che subito dopo si rivela una nave pirata, il cui equipaggio assalta mercantili uccidendo chi oppone resistenza. Al primo scalo scappa e rientra a Marsiglia. Jacob ancora giovane comincia ad interessarsi al pensiero anarchico, legge Proudhon, Kropotkin, Reclus, Malatesta, avvicinandosi così ai circoli anarchici e operai francesi. A 20 anni convinto definitivamente dell’ingiustizia del mondo dichiara la sua personale guerra alla società borghese, e con alcuni suoi compagni fonda il gruppo “Les travailleurs de la nuit” (“I lavoratori della notte”). -

The Bonnot Gang

by Richard Parry Contents Preface 5 One From illegality to illegalism i Making virtue of necessity 9 ii 6aiiu Max 15 Tvx} A new beginnir^ i Libertad2/ ii Cityul ihicves25 tii Slate of emergency 30 Three The rebels i Brussels Ji ii Pahs 42 lit Blood on the streets 44 br Strike! 45 Pour Anarchy in stAurbia i The move -#7 ii The Romainviile commune 51 tit Collapse of the Romainviile commune 57 vr Paris again 60 Five Sonnot i The *Little Corporal' 64 n In search of work 65 m Theillcgatist 66 iv Accidental death of an anarchist 70 Six The gan^forms i A meeting of egoists 73 ii Science on the side of the Proletariat 75 iii Looking for a target 76 Seven The birth of tragedy i The first ever hold-up by car 80 ii Crime doesn*t pay 84 m Jeux sans frontieres 88 iv Victor's dilemma 89 Copyrighled i .il Eight Kings ofthe road 1 Drivin' South W 11 The left hand of darkness 97 Stalemate 99 Nine Calm before the storm ft 1 •Simcnioff 103 u Of human bondage 104 Ul Dicudonnc in the hot seat 108 * Gamier's challenge 109 Ten Kings of the road (pan two) Atuck 113 U State of siege 117 Eleven The Sureie fights back 1 To catch an anarchist 120 u Hide and seek /2J 01 Exit Jouin 126 Twelve Txvilight ofthe idols 1 The wrath of Guichard 129 ii Shoot-out at 'The Red Nest' 133 4*4 Obituaries 137 iv To the Nuyem elation 139 V The last battle 142 Thirteen In the belly of the beast 1 Umbo 147 u Judgement 1S2 lU Execution 159 Fourteen TTte end of anarchism? 166 Epilogue 175 Map of Paris c, 1911 178 Appendix A / 79 Bibliography 182 Index 186 F - CopyrK ' Preface ON THE EVE of World War One a number of young anarchists came tc^cthcr in Paris determined to settle scores with bourgeois society. -

We Need a Bigger Boat Building a Mass Movement Beyond Extinction Rebellion

XXXX 1 vol 79:1 SUMMER 2019 anarchist journal by donation we need a bigger boat BUILDING A MASS MOVEMENT BEYOND EXTINCTION REBELLION Pic: Martin Hearn/Flickr CC inside this issue BEAT THE BAILIFFS MNEW OPPORTUNITIES n SEX WORK ANTI-FASCISM > BREXIT (OF COURSE) @ RADICAL MEDIA BEING SISTERS, NOT CISTERS a RADICAL BOOKS ROUNDUP 2 editorial Freedom is the oldest anarchist own efforts and partly with help from the due to our increased readership. We are publication in the English language. homeless folk of Whitechapel. also thinking about starting to commission Produced by Freedom Press, it was Seeing how both the Freedom News texts and offering a monetary donation of founded in 1886 and continues today as website and Freedom journal are growing, some sort in exchange: going either to the a bi-annual journal with an associated we have some ambitious plans for the author, or to the group of their choice. daily news site, publishing service and near future. Firstly, we will be seeking to We think that this could make it easier bookshop. Based in Whitechapel, the expand the Freedom News collective. for some folk to write a text for us, and Freedom Press collective runs on a non- Currently, the website is run by two — especially people from demographics profit and largely volunteer basis. occasionally three — volunteers. who otherwise may not be able to afford To find out more you can check out the We manage pretty well we daresay, but taking an afternoon off work to do so. This history and archives on our news site at if we are to keep growing we will need plan is only in its budding stages, and one freedomnews.org.uk, buy our books online more people on board.