Comets in Australian Aboriginal Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stargazer Vice President: James Bielaga (425) 337-4384 Jamesbielaga at Aol.Com P.O

1 - Volume MMVII. No. 1 January 2007 President: Mark Folkerts (425) 486-9733 folkerts at seanet.com The Stargazer Vice President: James Bielaga (425) 337-4384 jamesbielaga at aol.com P.O. Box 12746 Librarian: Mike Locke (425) 259-5995 mlocke at lionmts.com Everett, WA 98206 Treasurer: Carol Gore (360) 856-5135 janeway7C at aol.com Newsletter co-editor: Bill O’Neil (774) 253-0747 wonastrn at seanet.com Web assistance: Cody Gibson (425) 348-1608 sircody01 at comcast.net See EAS website at: (change ‘at’ to @ to send email) http://members.tripod.com/everett_astronomy nearby Diablo Lake. And then at night, discover the night sky like EAS BUSINESS… you've never seen it before. We hope you'll join us for a great weekend. July 13-15, North Cascades Environmental Learning Center North Cascades National Park. More information NEXT EAS MEETING – SATURDAY JANUARY 27TH including pricing, detailed program, and reservation forms available shortly, so please check back at Pacific Science AT 3:00 PM AT THE EVERETT PUBLIC LIBRARY, IN Center's website. THE AUDITORIUM (DOWNSTAIRS) http://www.pacsci.org/travel/astronomy_weekend.html People should also join and send mail to the mail list THIS MONTH'S MEETING PROGRAM: [email protected] to coordinate spur-of-the- Toby Smith, lecturer from the University of Washington moment observing get-togethers, on nights when the sky Astronomy department, will give a talk featuring a clears. We try to hold informal close-in star parties each month visualization presentation he has prepared called during the spring, summer, and fall months on a weekend near “Solar System Cinema”. -

Michael Kühn Detlev Auvermann RARE BOOKS

ANTIQUARIAT 55Michael Kühn Detlev Auvermann RARE BOOKS 1 Rolfinck’s copy ALESSANDRINI, Giulio. De medicina et medico dialogus, libris quinque distinctus. Zurich, Andreas Gessner, 1557. 4to, ff. [6], pp. AUTOLYKOS (AUTOLYCUS OF PYTANE). 356, ff. [8], with printer’s device on title and 7 woodcut initials; a few annotations in ink to the text; a very good copy in a strictly contemporary binding of blind-stamped pigskin, the upper cover stamped ‘1557’, red Autolyci De vario ortu et occasu astrorum inerrantium libri dvo nunc primum de graeca lingua in latinam edges, ties lacking; front-fly almost detached; contemporary ownership inscription of Werner Rolfinck on conuersi … de Vaticana Bibliotheca deprompti. Josepho Avria, neapolitano, interprete. Rome, Vincenzo title (see above), as well as a stamp and duplicate stamp of Breslau University library. Accolti, 1588. 4to, ff. [6], pp. 70, [2]; with large woodcut device on title, and several woodcut diagrams in the text; title a little browned, else a fine copy in 19th-century vellum-backed boards, new endpapers. EUR 3.800.- EUR 4.200.- First edition of Alessandrini’s medical dialogues, his most famous publication and a work of rare erudition. Very rare Latin edition, translated from a Greek manuscript at the Autolycus was a Greek mathematician and astronomer, who probably Giulio Alessandrini (or Julius Alexandrinus de Neustein) (1506–1590) was an Italian physician and author Vatican library, of Autolycus’ work on the rising and setting of the fixed flourished in the second half of the 4th century B.C., since he is said to of Trento who studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Padua, then mathematical science, stars. -

The Comet's Tale

THE COMET’S TALE Journal of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association Number 33, 2014 January Not the Comet of the Century 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) imaged by Damian Peach on 2013 December 24 using 106mm F5. STL-11k. LRGB. L: 7x2mins. RGB: 1x2mins. Today’s images of bright binocular comets rival drawings of Great Comets of the nineteenth century. Rather predictably the expected comet of the century Contents failed to materialise, however several of the other comets mentioned in the last issue, together with the Comet Section contacts 2 additional surprise shown above, put on good From the Director 2 appearances. 2011 L4 (PanSTARRS), 2012 F6 From the Secretary 3 (Lemmon), 2012 S1 (ISON) and 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) all Tales from the past 5 th became brighter than 6 magnitude and 2P/Encke, 2012 RAS meeting report 6 K5 (LINEAR), 2012 L2 (LINEAR), 2012 T5 (Bressi), Comet Section meeting report 9 2012 V2 (LINEAR), 2012 X1 (LINEAR), and 2013 V3 SPA meeting - Rob McNaught 13 (Nevski) were all binocular objects. Whether 2014 will Professional tales 14 bring such riches remains to be seen, but three comets The Legacy of Comet Hunters 16 are predicted to come within binocular range and we Project Alcock update 21 can hope for some new discoveries. We should get Review of observations 23 some spectacular close-up images of 67P/Churyumov- Prospects for 2014 44 Gerasimenko from the Rosetta spacecraft. BAA COMET SECTION NEWSLETTER 2 THE COMET’S TALE Comet Section contacts Director: Jonathan Shanklin, 11 City Road, CAMBRIDGE. CB1 1DP England. Phone: (+44) (0)1223 571250 (H) or (+44) (0)1223 221482 (W) Fax: (+44) (0)1223 221279 (W) E-Mail: [email protected] or [email protected] WWW page : http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~jds/ Assistant Director (Observations): Guy Hurst, 16 Westminster Close, Kempshott Rise, BASINGSTOKE, Hampshire. -

THE GREAT CHRIST COMET CHRIST GREAT the an Absolutely Astonishing Triumph.” COLIN R

“I am simply in awe of this book. THE GREAT CHRIST COMET An absolutely astonishing triumph.” COLIN R. NICHOLL ERIC METAXAS, New York Times best-selling author, Bonhoeffer The Star of Bethlehem is one of the greatest mysteries in astronomy and in the Bible. What was it? How did it prompt the Magi to set out on a long journey to Judea? How did it lead them to Jesus? THE In this groundbreaking book, Colin R. Nicholl makes the compelling case that the Star of Bethlehem could only have been a great comet. Taking a fresh look at the biblical text and drawing on the latest astronomical research, this beautifully illustrated volume will introduce readers to the Bethlehem Star in all of its glory. GREAT “A stunning book. It is now the definitive “In every respect this volume is a remarkable treatment of the subject.” achievement. I regard it as the most important J. P. MORELAND, Distinguished Professor book ever published on the Star of Bethlehem.” of Philosophy, Biola University GARY W. KRONK, author, Cometography; consultant, American Meteor Society “Erudite, engrossing, and compelling.” DUNCAN STEEL, comet expert, Armagh “Nicholl brilliantly tackles a subject that has CHRIST Observatory; author, Marking Time been debated for centuries. You will not be able to put this book down!” “An amazing study. The depth and breadth LOUIE GIGLIO, Pastor, Passion City Church, of learning that Nicholl displays is prodigious Atlanta, Georgia and persuasive.” GORDON WENHAM, Adjunct Professor “The most comprehensive interdisciplinary of Old Testament, Trinity College, Bristol synthesis of biblical and astronomical data COMET yet produced. -

Mpc 20051215

2005 DEC. 15 M.P.C. 55685 The MINOR PLANET CIRCULARS/MINOR PLANETS AND COMETS are published, on behalf of Commission 20 of the International Astronomical Union, usually in batches on or near the date of each full moon, by: Minor Planet Center, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, MA 02138, U.S.A. [email protected] or FAX 617{495{7231 (subscriptions) [email protected] (science) Phone 617{495{7244/7444/7440/7273 (for emergency use only). World-Wide Web address http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/iau/mpc.html ISSN 0736-6884 Brian G. Marsden, Director Gareth V. Williams, Associate Director Timothy B. Spahr, NEO Technical Specialist Syuichi Nakano, Andreas Doppler and Kyle E. Smalley, Associates Supported in part by the Brinson and TABASGO Foundations c Copyright 2005 Minor Planet Center Prepared using the Tamkin Foundation Computer Network ° EDITORIAL NOTICE 147 Osservatorio Astron¶omico di Suno. Observers L. Buzzi, D. Crespi, S. Foglia, G. Galli, S. Minuto, V. Sacco. Measurers L. Buzzi, S. Foglia, G. Galli, The Minor Planet Center is pleased to acknowledge with thanks another gen- S. Minuto. 0.40-m /4 reflector + CCD. erous donation from F. K. Edmondson (Bloomington, IN; senior former president of f 170 Observatorio de Begues. Observer J. Manteca. 0.36-m /10 Schmidt- IAU Commission 20). f Cassegrain + CCD. The next batch of Minor Planet Circulars will be issued on or about 2006 Feb. 201 Jonathan B. Postel Observatory. Observer V. Pozzoli. 0.30-m f/10 reflector 13. There will be no Circulars during January. + CCD. 204 Schiaparelli Observatory. Observer L. -

Kosmos, and Uranus

K O 2 M O 2 : A General £>urbep OF THE PHYSICAL PHENOMENA OF THE UNIVERSE. BY ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT. Vol. I. Natune vero rerum vis atque majestaa in omnibus moment is fide caret, si quia modo partes ejus ac non totam compiectatur animo. Pi- in., Hist. Nat. lib. yH. cap. 1. LONDON: HIPPOLYTE BAILLIERE, PUBLISHER, AND FOREIGN BOOKSELLER, 219, REGENT STREET. 1845. TCI HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF PRUSSIA, FREDERICK-WILLIAM IV, THIS SURVEY OF THE PHYSICAL HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSE, 3Jg Betifcatrti, WITH FEELINGS OF DEEP RESPECT AND HEARTFELT GRATITUDE, BY ALEXANDER von HUMBOLDT. PREFACE. In the evening of a long and active life, I present the public with a work the indefinite outlines of which have floated in my mind for almost half a century. I have, in many moods, regarded this work as impracticable; and when I had abandoned it, have still, rashly perhaps, returned to it again. — I lay it before my contemporaries with the diffidence which a reasonable mistrust in the measure ^of my abilities inspires. I also endeavour to forget, that works long looked for are commonly less indulgently received. If circumstances, and an irresistible propensity to pur sue science of various kinds, led me to devote myself for many years, and almost exclusively as it seemed, to parti cular branches, — to descriptive botany, geology, chemistry, astronomical observation and terrestrial magnetism, — as preparatives for a journey on a great scale, the special purpose of my studies was always one still higher than this. My main object was to prepare myself to compre Vlll PREFACE. -

Solutions to Odd Exercises

Solutions to all Odd Problems of BASIC CALCULUS OF PLANETARY ORBITS AND INTERPLANETARY FLIGHT Chapter 1. Solutions of Odd Problems Problem 1.1. In Figure 1.33, let V represent Mercury instead of Venus. Let α = \V ES be the maximum angle that Copernicus observed after measuring it many times. As in the case of Venus, α is at its maximum when the line of sight EV is tangent to the orbit of Mercury (assumed to be a circle). This means that when α is at its maximum, the triangle EV S is a right triangle VS with right angle at V . Since Copernicus concluded from his observations that ES ≈ 0:38, we VS know that sin α = ES ≈ 0:38. Working backward (today we would push the inverse sine button 1 ◦ of a calculator) provides the conclusion that α ≈ 22 3 . So the maximum angle that Copernicus 1 ◦ observed was approximately 22 3 . From this he could conclude that EV ≈ 0:38. Problem 1.3. Since the lines of site BA and B0A of Figure 1.36a are parallel, Figure 1.36b tells us that (α + β) + (α0 + β0) = π as asserted. By a look at the triangle ∆BB0M, β + β0 + θ = π. So β + β0 = π − θ, and hence α0 + α + (π − θ) = π. So θ = α + α0. Problem 1.5. Let R the radius of the circle of Figure 1.40b. Turn to Figure 1.40a, and notice that cos ' = R . The law of cosines applied to the triangle of Figure 1.40b tells us that (BB0)2 = rE R2 + R2 − 2R · R cos θ = 2R2(1 − cos θ). -

The Science of Sungrazers, Sunskirters, and Other Near-Sun Comets

Space Sci Rev (2018) 214:20 DOI 10.1007/s11214-017-0446-5 The Science of Sungrazers, Sunskirters, and Other Near-Sun Comets Geraint H. Jones1,2 · Matthew M. Knight3,4 · Karl Battams5 · Daniel C. Boice6,7,8 · John Brown9 · Silvio Giordano10 · John Raymond11 · Colin Snodgrass12,13 · Jordan K. Steckloff14,15,16 · Paul Weissman14 · Alan Fitzsimmons17 · Carey Lisse18 · Cyrielle Opitom19,20 · Kimberley S. Birkett1,2,21 · Maciej Bzowski22 · Alice Decock19,23 · Ingrid Mann24,25 · Yudish Ramanjooloo1,2,26 · Patrick McCauley11 Received: 1 March 2017 / Accepted: 15 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This review addresses our current understanding of comets that venture close to the Sun, and are hence exposed to much more extreme conditions than comets that are typ- ically studied from Earth. The extreme solar heating and plasma environments that these objects encounter change many aspects of their behaviour, thus yielding valuable informa- tion on both the comets themselves that complements other data we have on primitive solar system bodies, as well as on the near-solar environment which they traverse. We propose clear definitions for these comets: We use the term near-Sun comets to encompass all ob- B G.H. Jones [email protected] 1 Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, Holmbury St. Mary, Dorking, UK 2 The Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL/Birkbeck, London, UK 3 University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA 4 Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ, USA -

The Comet's Tale

THE COMET’S TALE Newsletter of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association Number 29, 2010 January The Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT) The Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams be supernovae, comets, novae and other unusual (CBAT) has recently celebrated the 125th anniversary variable stars, and satellites of minor planets and major since its founding by the editors of Astronomische planets – both discovery information and follow-up Nachrichten at Kiel, Germany, in late 1882. The information. Contributors also send information to the immediate cause was the sudden appearance of the CBAT regarding novae in other galaxies, and while great September sungrazing comet, for which a publication is generally made of novae in galaxies other coordinated worldwide center was seen to be much than M31, the CBAT webpage devoted to M31 novae needed, due to problems in getting proper information now appears satisfactorily to provide a venue for circulated quickly to the astronomical community. The designating and announcing new novae in that nearby CBAT moved to Copenhagen Observatory out of galaxy, with suitable follow-up observations also necessity during World War I, where it took on IAU provided there. Following discussion with IAU acceptance in 1922 (after an initial 2-year stint of an Commission 22 in Prague in 2006, reports on new IAU Central Bureau floundered in Brussels); the IAU's meteor showers also are now routinely published by the Central Bureau remained at Copenhagen until its CBAT. transfer to Cambridge at the start of 1965 (where Harvard College Observatory had maintained the The years 2006-2008 continued the marked transition western hemisphere's central bureau for astronomical toward the increased issuance of Central Bureau telegrams since 1883). -

Ice & Stone 2020

Ice & Stone 2020 WEEK 9: FEBRUARY 23-29, 2020 Presented by The Earthrise Institute # 9 Authored by Alan Hale This week in history FEBRUARY 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 FEBRUARY 23, 1988: David Levy obtains the final visual observation of Comet 1P/Halley during its 1986 eturn,r using the 1.5-meter telescope at Catalina Observatory in Arizona. The comet was located 8.0 AU from the sun and appeared at 17th magnitude. FEBRUARY 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 FEBRUARY 24, 1979: The U.S. Defense Department satellite P78-1 is launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. One of P78-1’s instruments was the SOLWIND coronagraph, which detected ten comets between 1979 and 1984, nine of which were Kreutz sungrazers and the first of these being the first comet ever discovered from space. SOLWIND continued to operate up until the time P78-1 was deliberately destroyed in September 1985 as part of an Anti-Satellite weapon (ASAT) test. The first SOLWIND comet is a future “Comet of the Week” and Kreutz sungrazers as a whole are the subject of a future “Special Topics” presentation. FEBRUARY 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 FEBRUARY 25, 1976: Comet West 1975n passes through perihelion at a heliocentric distance of 0.197 AU. Comet West, which is next week’s “Comet of the Week,” was one of the brightest comets that appeared during the second half of the 20th Century, and I personally consider it the best comet I have ever seen. COVER IMAGEs CREDITS: Front cover: Three impact craters of different sizes, arranged in the shape of a snowman, make up one of the most striking features on Vesta, as seen in this view from NASA’s Dawn mission. -

Implications of Magnitude Distribution Comparisons Between Trans-Neptunian Objects and Comets

Implications of Magnitude Distribution Comparisons between Trans-Neptunian Objects and Comets by Alexander J. Willman, Jr. SpSt 997 “Independent Study” Department of Space Studies University of North Dakota Dr. C. A. Wood, Advisor December 1, 1995 Implications of Magnitude Distribution Comparisons between Trans-Neptunian Objects and Comets Abstract The population of observed trans-neptunian objects has a fairly well-defined magnitude distribution, however, the population of observed short-period comets does not. This analysis of the population distributions of observed trans-neptunian objects (TNOs) and short-period comets (SPCs) indicates that the observed number of TNOs and SPCs is insufficient to judge conclusively whether the trans-neptunian objects are related to the short-period comets or whether the TNOs are part of the Kuiper belt from which the SPCs are believed to be derived. Differences in the population distributions of TNOs and SPCs indicate that the TNOs are not representative of the Kuiper belt as a whole, even if they are part of the Kuiper belt. Further analysis of the population distributions of comets and the TNOs has provided additional information and some predictions about the populations’ characteristics. This derived information includes the facts that: the six brightest SPCs for which H10 magnitudes have been calculated likely belong to the Oort cloud population (long-period) of comets instead of the Kuiper belt population of comets; Pluto and Charon are likely to belong to the TNO population instead of the major planet population; there are likely to be ~109 TNOs in the Kuiper belt, including many Pluto-sized objects, massing a total of ~1025 kg in all. -

The Comet's Tale

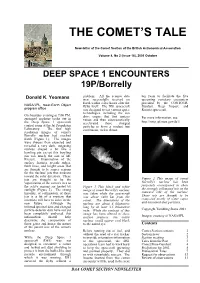

THE COMET’S TALE Newsletter of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association Volume 8, No 2 (Issue 16), 2001 October DEEP SPACE 1 ENCOUNTERS 19P/Borrelly problem. All the science data ten years to facilitate the five Donald K. Yeomans were successfully received on upcoming cometary encounters Earth within a few hours after the provided by the CONTOUR, NASA/JPL, Near-Earth Object flyby itself. The DS1 spacecraft Stardust, Deep Impact, and program office was designed to test various space Rosetta spacecraft. technologies including the ion On Saturday evening at 7:00 PM, drive engine that first ionizes For more information, see: sustained applause broke out in xenon and then electrostatically the Deep Space 1 spacecraft accelerated these charged http://nmp.jpl.nasa.gov/ds1/ control room at the Jet Propulsion particles to form a modest, but Laboratory. The first high continuous, rocket thrust. resolution images of comet's Borrelly nucleus had reached Earth (Figure 1). The images were sharper than expected and revealed a very dark, outgasing nucleus shaped a bit like a bowling pin except this bowling pin was nearly the size of Mt. Everest. Examination of the surface features reveals ridges, fault lines, and bright areas that are thought to be source regions for the nucleus' jets that emanate toward the solar direction. These Figure 2 This image of comet jets are thought to be the vaporization of the comet's ices as Borrelly's nucleus has been the active regions are heated by Figure 1 This black and white purposely overexposed to show sunlight (Figure 2).