Kosmos, and Uranus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Michael Kühn Detlev Auvermann RARE BOOKS

ANTIQUARIAT 55Michael Kühn Detlev Auvermann RARE BOOKS 1 Rolfinck’s copy ALESSANDRINI, Giulio. De medicina et medico dialogus, libris quinque distinctus. Zurich, Andreas Gessner, 1557. 4to, ff. [6], pp. AUTOLYKOS (AUTOLYCUS OF PYTANE). 356, ff. [8], with printer’s device on title and 7 woodcut initials; a few annotations in ink to the text; a very good copy in a strictly contemporary binding of blind-stamped pigskin, the upper cover stamped ‘1557’, red Autolyci De vario ortu et occasu astrorum inerrantium libri dvo nunc primum de graeca lingua in latinam edges, ties lacking; front-fly almost detached; contemporary ownership inscription of Werner Rolfinck on conuersi … de Vaticana Bibliotheca deprompti. Josepho Avria, neapolitano, interprete. Rome, Vincenzo title (see above), as well as a stamp and duplicate stamp of Breslau University library. Accolti, 1588. 4to, ff. [6], pp. 70, [2]; with large woodcut device on title, and several woodcut diagrams in the text; title a little browned, else a fine copy in 19th-century vellum-backed boards, new endpapers. EUR 3.800.- EUR 4.200.- First edition of Alessandrini’s medical dialogues, his most famous publication and a work of rare erudition. Very rare Latin edition, translated from a Greek manuscript at the Autolycus was a Greek mathematician and astronomer, who probably Giulio Alessandrini (or Julius Alexandrinus de Neustein) (1506–1590) was an Italian physician and author Vatican library, of Autolycus’ work on the rising and setting of the fixed flourished in the second half of the 4th century B.C., since he is said to of Trento who studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Padua, then mathematical science, stars. -

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = Easy = Not Too Difficult = Difficult but Possible

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = easy = not too difficult = difficult but possible 1. Sigma Cassiopeiae (STF 3049). 23 hr 59.0 min +55 deg 45 min This system is tight but very beautiful. Use a high magnification (150x or more). Primary: 5.2, yellow or white Seconary: 7.2 (3.0″), blue 2. Eta Cassiopeiae (Achird, STF 60). 00 hr 49.1 min +57 deg 49 min This is a multiple system with many stars, but I will restrict myself to the brightest one here. Primary: 3.5, yellow. Secondary: 7.4 (13.2″), purple or brown 3. 65 Piscium (STF 61). 00 hr 49.9 min +27 deg 43 min Primary: 6.3, yellow Secondary: 6.3 (4.1″), yellow 4. Psi-1 Piscium (STF 88). 01 hr 05.7 min +21 deg 28 min This double forms a T-shaped asterism with Psi-2, Psi-3 and Chi Piscium. Psi-1 is the uppermost of the four. Primary: 5.3, yellow or white Secondary: 5.5 (29.7), yellow or white 5. Zeta Piscium (STF 100). 01 hr 13.7 min +07 deg 35 min Primary: 5.2, white or yellow Secondary: 6.3, white or lilac (or blue) 6. Gamma Arietis (Mesarthim, STF 180). 01 hr 53.5 min +19 deg 18 min “The Ram’s Eyes” Primary: 4.5, white Secondary: 4.6 (7.5″), white 7. Lambda Arietis (H 5 12). 01 hr 57.9 min +23 deg 36 min Primary: 4.8, white or yellow Secondary: 6.7 (37.1″), silver-white or blue 8. -

The Comet's Tale

THE COMET’S TALE Journal of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association Number 33, 2014 January Not the Comet of the Century 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) imaged by Damian Peach on 2013 December 24 using 106mm F5. STL-11k. LRGB. L: 7x2mins. RGB: 1x2mins. Today’s images of bright binocular comets rival drawings of Great Comets of the nineteenth century. Rather predictably the expected comet of the century Contents failed to materialise, however several of the other comets mentioned in the last issue, together with the Comet Section contacts 2 additional surprise shown above, put on good From the Director 2 appearances. 2011 L4 (PanSTARRS), 2012 F6 From the Secretary 3 (Lemmon), 2012 S1 (ISON) and 2013 R1 (Lovejoy) all Tales from the past 5 th became brighter than 6 magnitude and 2P/Encke, 2012 RAS meeting report 6 K5 (LINEAR), 2012 L2 (LINEAR), 2012 T5 (Bressi), Comet Section meeting report 9 2012 V2 (LINEAR), 2012 X1 (LINEAR), and 2013 V3 SPA meeting - Rob McNaught 13 (Nevski) were all binocular objects. Whether 2014 will Professional tales 14 bring such riches remains to be seen, but three comets The Legacy of Comet Hunters 16 are predicted to come within binocular range and we Project Alcock update 21 can hope for some new discoveries. We should get Review of observations 23 some spectacular close-up images of 67P/Churyumov- Prospects for 2014 44 Gerasimenko from the Rosetta spacecraft. BAA COMET SECTION NEWSLETTER 2 THE COMET’S TALE Comet Section contacts Director: Jonathan Shanklin, 11 City Road, CAMBRIDGE. CB1 1DP England. Phone: (+44) (0)1223 571250 (H) or (+44) (0)1223 221482 (W) Fax: (+44) (0)1223 221279 (W) E-Mail: [email protected] or [email protected] WWW page : http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~jds/ Assistant Director (Observations): Guy Hurst, 16 Westminster Close, Kempshott Rise, BASINGSTOKE, Hampshire. -

Downloads/ Astero2007.Pdf) and by Aerts Et Al (2010)

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. i Fundamental Properties of Solar-Type Eclipsing Binary Stars, and Kinematic Biases of Exoplanet Host Stars Richard J. Hutcheon Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research Institute: School of Environmental and Physical Sciences and Applied Mathematics. University of Keele June 2015 ii iii Abstract This thesis is in three parts: 1) a kinematical study of exoplanet host stars, 2) a study of the detached eclipsing binary V1094 Tau and 3) and observations of other eclipsing binaries. Part I investigates kinematical biases between two methods of detecting exoplanets; the ground based transit and radial velocity methods. Distances of the host stars from each method lie in almost non-overlapping groups. Samples of host stars from each group are selected. They are compared by means of matching comparison samples of stars not known to have exoplanets. The detection methods are found to introduce a negligible bias into the metallicities of the host stars but the ground based transit method introduces a median age bias of about -2 Gyr. -

Thursday, December 22Nd Swap Meet & Potluck Get-Together Next First

Io – December 2011 p.1 IO - December 2011 Issue 2011-12 PO Box 7264 Eugene Astronomical Society Annual Club Dues $25 Springfield, OR 97475 President: Sam Pitts - 688-7330 www.eugeneastro.org Secretary: Jerry Oltion - 343-4758 Additional Board members: EAS is a proud member of: Jacob Strandlien, Tony Dandurand, John Loper. Next Meeting: Thursday, December 22nd Swap Meet & Potluck Get-Together Our December meeting will be a chance to visit and share a potluck dinner with fellow amateur astronomers, plus swap extra gear for new and exciting equipment from somebody else’s stash. Bring some food to share and any astronomy gear you’d like to sell, trade, or give away. We will have on hand some of the gear that was donated to the club this summer, including mirrors, lenses, blanks, telescope parts, and even entire telescopes. Come check out the bargains and visit with your fellow amateur astronomers in a relaxed evening before Christmas. We also encourage people to bring any new gear or projects they would like to show the rest of the club. The meeting is at 7:00 on December 22nd at EWEB’s Community Room, 500 E. 4th in Eugene. Next First Quarter Fridays: December 2nd and 30th Our November star party was clouded out, along with a good deal of the month afterward. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it is: I changed the date in the previous sentence from October to November and left the rest of the sentence intact. Yes, our autumn weather is predictable. Here’s hoping for a lucky break in the weather for our two December star parties. -

Astronomical Coordinate Systems

Appendix 1 Astronomical Coordinate Systems A basic requirement for studying the heavens is being able to determine where in the sky things are located. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each sys- tem uses a coordinate grid projected on the celestial sphere, which is similar to the geographic coor- dinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth’s equator). Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The Equatorial Coordinate System The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the most closely related to the geographic coordinate system because they use the same funda- mental plane and poles. The projection of the Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles onto the celestial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate sys- tems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth and rotates as the Earth does. The Equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but it’s really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec. for short). It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. -

Mpc 20051215

2005 DEC. 15 M.P.C. 55685 The MINOR PLANET CIRCULARS/MINOR PLANETS AND COMETS are published, on behalf of Commission 20 of the International Astronomical Union, usually in batches on or near the date of each full moon, by: Minor Planet Center, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, MA 02138, U.S.A. [email protected] or FAX 617{495{7231 (subscriptions) [email protected] (science) Phone 617{495{7244/7444/7440/7273 (for emergency use only). World-Wide Web address http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/iau/mpc.html ISSN 0736-6884 Brian G. Marsden, Director Gareth V. Williams, Associate Director Timothy B. Spahr, NEO Technical Specialist Syuichi Nakano, Andreas Doppler and Kyle E. Smalley, Associates Supported in part by the Brinson and TABASGO Foundations c Copyright 2005 Minor Planet Center Prepared using the Tamkin Foundation Computer Network ° EDITORIAL NOTICE 147 Osservatorio Astron¶omico di Suno. Observers L. Buzzi, D. Crespi, S. Foglia, G. Galli, S. Minuto, V. Sacco. Measurers L. Buzzi, S. Foglia, G. Galli, The Minor Planet Center is pleased to acknowledge with thanks another gen- S. Minuto. 0.40-m /4 reflector + CCD. erous donation from F. K. Edmondson (Bloomington, IN; senior former president of f 170 Observatorio de Begues. Observer J. Manteca. 0.36-m /10 Schmidt- IAU Commission 20). f Cassegrain + CCD. The next batch of Minor Planet Circulars will be issued on or about 2006 Feb. 201 Jonathan B. Postel Observatory. Observer V. Pozzoli. 0.30-m f/10 reflector 13. There will be no Circulars during January. + CCD. 204 Schiaparelli Observatory. Observer L. -

The Prairie Astronomer February 2016 Volume 57, Issue #2

The Prairie Astronomer February 2016 Volume 57, Issue #2 February Gravitational Waves Program: Observing Observed Programs Jim Kvasnicka Image Credit: SXS MSRAL The Newsletter of the Prairie Astronomy Club The Prairie Astronomer NEXT PAC MEETING: February 23, 7:30pm at Hyde Observatory CONTENTS PROGRAM 4 Meeting Minutes Observing Programs, by Jim Kvasnicka. 5 Double Stars Jim will present an overview of the Astronomical League’s observing programs. It will benefit any new members who 7 Close Encounters are thinking of starting an observing program. It will cover 9 TX68 how to get started, which program to start with. He will also review the observing awards earned by PAC members. 10 Galaxies & Asteroids 13 Tethys 14 LIGO 17 March Observing 18 Puppis FUTURE PROGRAMS 19 Closest New Stars March: Space Law Part I - Mark Ellis 10 From the Archives April: Space Law Part II - Elsbeth Magilton & Prof Frans Von der Dunk June: Solar Star Party 21 Club Information August: NSP Review Buy the book! The Prairie Astronomy Club: Fifty Years of Amateur Astronomy. Order online from Amazon or lulu.com. EVENTS PAC Meeting PAC Meeting Tuesday February 23rd, 2016, 7:30pm Hyde Observatory PAC E-MAIL: PAC Meeting [email protected] Tuesday March 29th, 2016, 7:30pm Hyde Observatory Astronomy Day, Sunday, April 17 at Morrill Hall PAC-LIST: Subscribe through GoogleGroups. PAC Meeting To post messages to the list, send Tuesday April 26th, 2016, 7:30pm to the address: Hyde Observatory [email protected] Newsletter submission deadline March 19 2016 STAR PARTY DATES ADDRESS The Prairie Astronomer c/o The Prairie Astronomy Club, Inc. -

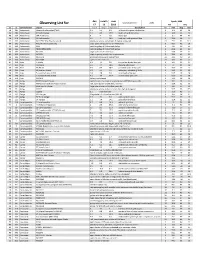

Observing List

day month year Epoch 2000 local clock time: 2.00 Observing List for 17 11 2019 RA DEC alt az Constellation object mag A mag B Separation description hr min deg min 58 286 Andromeda Gamma Andromedae (*266) 2.3 5.5 9.8 yellow & blue green double star 2 3.9 42 19 40 283 Andromeda Pi Andromedae 4.4 8.6 35.9 bright white & faint blue 0 36.9 33 43 48 295 Andromeda STF 79 (Struve) 6 7 7.8 bluish pair 1 0.1 44 42 59 279 Andromeda 59 Andromedae 6.5 7 16.6 neat pair, both greenish blue 2 10.9 39 2 32 301 Andromeda NGC 7662 (The Blue Snowball) planetary nebula, fairly bright & slightly elongated 23 25.9 42 32.1 44 292 Andromeda M31 (Andromeda Galaxy) large sprial arm galaxy like the Milky Way 0 42.7 41 16 44 291 Andromeda M32 satellite galaxy of Andromeda Galaxy 0 42.7 40 52 44 293 Andromeda M110 (NGC205) satellite galaxy of Andromeda Galaxy 0 40.4 41 41 56 279 Andromeda NGC752 large open cluster of 60 stars 1 57.8 37 41 62 285 Andromeda NGC891 edge on galaxy, needle-like in appearance 2 22.6 42 21 30 300 Andromeda NGC7640 elongated galaxy with mottled halo 23 22.1 40 51 35 308 Andromeda NGC7686 open cluster of 20 stars 23 30.2 49 8 47 258 Aries 1 Arietis 6.2 7.2 2.8 fine yellow & pale blue pair 1 50.1 22 17 57 250 Aries 30 Arietis 6.6 7.4 38.6 pleasing yellow pair 2 37 24 39 59 253 Aries 33 Arietis 5.5 8.4 28.6 yellowish-white & blue pair 2 40.7 27 4 59 239 Aries 48, Epsilon Arietis 5.2 5.5 1.5 white pair, splittable @ 150x 2 59.2 21 20 46 254 Aries 5, Gamma Arietis (*262) 4.8 4.8 7.8 nice bluish-white pair 1 53.5 19 18 49 258 Aries 9, Lambda Arietis -

Atmospheric Activity in Red Dwarf Stars

CONTENTS SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS PAPERS ON CHROMOSPHERIC LINES IN RED DWARF FLARE STARS I. AD LEONIS AND GX ANDROMEDAE B. R. Pettersen and L. A. Coleman, 1981, Ap.J. 251, 571. II. EV LACERTAE, EQ PEGASI A, AND V1054 OPHIUCHI B. R. Pettersen, D. S. Evans, and L. A. Coleman, 1984, Ap.J. 282, 214. III. AU MICROSCOPII AND YY GEMINORUM B. R. Pettersen, 1986, Astr. Ap., in press. IV. V1005 ORIONIS AND DK LEONIS B. R. Pettersen, 1986, Astr. Ap., submitted. V. EQ VIRGINIS AND BY DRACONIS B. R. Pettersen, 1986, Astr. Ap., submitted. PAPERS ON FLARE ACTIVITY VI. THE FLARE ACTIVITY OF AD LEONIS B. R. Pettersen, L. A. Coleman, and D. S. Evans, 1984, Ap.J.suppl. 5£, 275. VII. DISCOVERY OF FLARE ACTIVITY ON THE VERY LOW LUMINOSITY RED DWARF G 51-15 B. R. Pettersen, 1981, Astr. Ap. 95, 135. VIII. THE FLARE ACTIVITY OF V780 TAU B. R. Pettersen, 1983, Astr. Ap. 120, 192. IX. DISCOVERY OF FLARE ACTIVITY ON THE LOW LUMINOSITY RED DWARF SYSTEM G 9-38 AB B. R. Pettersen, 1985, Astr. Ap. 148, 151. Den som påstår seg ferdig utlært, - han er ikke utlært, men ferdig. 1 ATMOSPHERIC ACTIVITY IN RED DWARF STARS SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS Active and inactive stars of similar mass and luminosity have similar physical conditions in their photospheres/ outside of magnetically disturbed regions. Such field structures give rise to stellar activity, which manifests itself at all heights of the atmosphere. Observations of uneven distributions of flux across the stellar disk have led to the discovery of photospheric starspots, chromospheric plage areas, and coronal holes. -

Astronomie Pentru Şcolari

NICU GOGA CARTE DE ASTRONOMIE Editura REVERS CRAIOVA, 2010 Referent ştiinţific: Prof. univ.dr. Radu Constantinescu Editura Revers ISBN: 978-606-92381-6-5 2 În contextul actual al restructurării învăţământului obligatoriu, precum şi al unei manifeste lipse de interes din partea tinerei generaţii pentru studiul disciplinelor din aria curiculară Ştiinţe, se impune o intensificare a activităţilor de promovare a diferitelor discipline ştiinţifice. Dintre aceste discipline Astronomia ocupă un rol prioritar, având în vedere că ea intermediază tinerilor posibilitatea de a învăţa despre lumea în care trăiesc, de a afla tainele şi legile care guvernează Universul. În plus, anul 2009 a căpătat o co-notaţie specială prin declararea lui de către UNESCO drept „Anul Internaţional al Astronomiei”. În acest context, domnul profesor Nicu Goga ne propune acum o a doua carte cu tematică de Astronomie. După apariţia lucrării Geneza, evoluţia şi sfârşitul Universului, un volum care s+a bucurat de un real succes, apariţia lucrării „Carte de Astronomie” reprezintă un adevărat eveniment editorial, cu atât mai mult cu cât ea constitue în acelaşi timp un material monografic şi un material cu caracter didactic. Cartea este structurată în 13 capitole, trecând în revistă problematica generală a Astronomiei cu puţine elemente de Cosmologie. Cartea îşi propune şi reuşeşte pe deplin să ofere răspunsuri la câteva întrebări fundamentale şi tulburătoare legate de existenţa fiinţei umane şi a dimensiunii cosmice a acestei existenţe, incită la dialog şi la dorinţa de cunoaştere. Consider că, în ansamblul său, cartea poate contribui la îmbunătăţirea educaţiei ştiinţifice a tinerilor elevi şi este deosebit de utilă pentru toţi „actorii” implicaţi în procesul de predare-învăţare: elevi, părinţi, profesori.