Barkby 1086-1524 Pp.46-61

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pink Pages Leicester

Pink Pages Leicester Call Pink Pages on 0116 260 00 88 Delivered free to homes and businesses in Thrussington Rearsby, East Goscote, Queniborough, Syston, Barkby Thurmaston Village. Zone 1 - January 2021 www.pink-pages.co.ukPlease mention Pink Pages email: when [email protected] responding to adverts 1 2 To advertise please call 0116 260 00 88 Please mention Pink Pages when responding to adverts 3 Butter�ly Funeral Services Independent Funeral Directors “What the caterpillar perceives as the end, to the Butter�ly is just the beginning” Private Chapel of Rest Pre Paid Funeral Plans Funerals By Shane Mousley Dip FD 0116 269 8120 Day or Night 4 Merchants Common, East Goscote LE7 3XR 4 To advertise please call 0116 260 00 88 Please mention Pink Pages when responding to adverts 5 LEICESTERSHIRE'S CARPET & BED SUPERSTORES We stock 1000’s rolls of carpet and hundreds of mattresses all ready for super quick delivery! We're Leicestershire's BIGGEST hard flooring superstores! Leicestershire's BIGGEST bed stockist, over 150 beds on display. Bring this flyer with you for an extra 5% oo any GET purchase! 5% OFF SEE MORE AT EXCELLENT REVIEWS colourbank.co.uk/testimonials 0116 276 76 60 45 CREST RISE | (OFF ‘LEWISHER RD’) | LE4 9EX LEICESTER *If within 7 days of purchase you find a lower fully fitted price (including fitting, underlay, grippers, strips and del ivery) on any of Colourbank's stock carpets we will refund the difference (proof required) *If within 7 days of purchase you find a Also at lower delivered store price on any of Colourbank's stock beds or mattresses we will refund the difference (proof required) SOP means the price we charge if we don't stock the colour or width shown. -

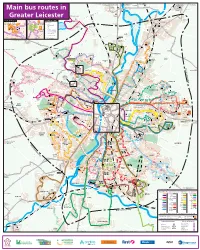

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire Results

Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire Results Page | 0 Contents 1. Introduction P. 2 2. Questionnaire Methodology P. 2 3. Summary P. 2 4. Results P. 5 Vision for Queniborough in 2028 P. 6 Traffic & Transport P. 9 Facilities & Services P. 15 Housing P. 19 Heritage P. 32 Environment P. 33 Employment & Business P. 42 Anything Else P. 47 5. Appendix 1 – The Questionnaire P. 56 Page | 1 Residents Questionnaire 1) Introduction The Neighbourhood Plan process will provide residents, businesses, service providers and local organisations with a unique opportunity to help guide development within the designated area, plan the future delivery of local services and facilities, and ensure that Queniborough remains a vibrant and sustainable place to live, work, and do business. To support the successful development of the Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan, the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland) supported Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group to undertake a consultation with households in the designated area. 2) Questionnaire Methodology A questionnaire was developed by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group in conjunction with the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland). The final version of the questionnaire (see Appendix 1) and the basis of this report, was available for every household. The questionnaire was 16 sides of A4 in length including the instructions, guidance notes providing further background and context and a map of the designated area. Approximately 1500 questionnaires were delivered to households in the designated area during March 2019 by members and volunteers of the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group and included an envelope into which the completed questionnaires could be enclosed, sealed and returned at 3 drop of points around the parish. -

June 2013 the Parish of Birstall and Wanlip

JUNE 2013 THE PARISH OF BIRSTALL AND WANLIP 3 PARISH DIARY JUNE—AUGUST 2013 JUNE 2nd 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 16th 6pm Christian Unity Sunday Evensong at Wanlip with Speaker from “GATES” 22nd 9am Coach trip to Gloucester 29/30th Birstall Gala 30th Service on the Park JULY 7th 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 8th—12th Parish Holiday to Cober Hill 27th 10 am Parish Away Day at Nanpantan AUGUST 1st 10 am ‘All Together’ service led by Home Groups 4th 7.30 pm Home Groups Get Together 11th 10 am Mothers’ Union Service 26th 2pm Parish Garden Fete on the Church Lawn Details of our regular services can be found on page 6 Please see church information sheets and/or website www.birstall.org for further information 4 Welcome Welcome to the summer edition of ‘Link’. I hope you find it informative, useful and interesting. It is the first put together ‘under new management’ since our friend - and editor of many years - Maureen Holland died in April. It is due to Maureen’s efforts that ‘Link’ exists today; a link with the Church which we hope to continue to provide you with for a long time to come. Our website editor, Gill Pope, has taken over the production editorial role, Noreen Talbot continues as commissioning editor. Gill and Noreen welcome your contributions as well as your feedback in order to help them make it the magazine that you look forward to receiving and reading each quarter. Thank you for your continued interest in, and support of, the Church. -

Ii'i::.L.':J';Lii:I,I.I.:.I.:.:.'L:..Iili::'I,I:Il;Iii'i,Ii-Ii-.Ii...L.I''i,.:Jii.Ii'iiiijjiiiiiii:J.I::I:.I:I:::I:Ii.:I:Iiiji:.I.Iii

L LEICESTERSHIRE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY tt \, iiii:j:::::i::;::;;::ii:;::i:Oocasional:PUblicati6fiS:iSeried:::;::::r:r:iii:::::l::;ll|:It.':i:j::::::::;::::::ir:;::i:.roc35fflflef::llll9ll9aIlonE:iPgtI9,Ei:.;:::.l:i:iii:i:i:i:i:ii.'.r ::i:::::::::;:i:i::::::,:::::,:::::::::::::::::::::l:::j,,,,,,.,:,:,,,i,.,,:,,,::::.:.:::::::::::i::::.,:,::i::,:ii,,,,,,ij::.i::::l:ill.:.:,: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::.:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::.::::::::::':::::::::: ...:::::i:::i:::::::l ::.::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: .:.:.::.:.:.: : : t :.:. .: : :.: : : : :.:.: :'r:r:!:iii:i.ii::!:::i:!:!.l.i::::i:ii::il.i'tili;:i:i::::NUmbgi.l:lll:,,;:::ll;:::;::::::,:,:iit;;;:::i:::::::,;:,::i;i:::,,t,,,r: ii'i::.l.':j';lii:i,i.i.:.i.:.:.'l:..iili::'i,i:il;iii'i,iI-ii-.ii...l.i''i,.:jii.ii'iiiijjiiiiiii:j.i::i:.i:i:::i:ii.:i:iiiji:.i.iii. ::iiiir:::;:i;:;;iiiiirji:i;;iii:i;i:.:i;;;iii;ii;iS€ptember.,1:99S:i:i:iri;iii:t::ii:::ii::i:i:::::::i:i:i:::l::::ii:l - v ,ss^, 0957 1019 AdrianRussell, 15, St SwithinsRoad, Leicester INTRODUCTION On 12th January1994 local Lepidopterarecorders met to discussways of revitalisingthe LeicestershireLepidoptera Recording Scheme. There was a consensusthat feedbackto recorders shouldbe improved,and it was agreedthat an annualsummary of Lepidopterarecords would be produced.The establishment of a validationpanel and a numberof othermeasures were also agreed. Thesemeasures will be implementedfully in relationto 1995records. As an indicationof thingsto come, I decidedto producea summaryof 1994records submitted to LeicestershireLepidoptera Recording Scheme. These records have all beenprocessed and mostare alreadyincorporated into BIOSPIN, the computerdatabase used by LeicestershireBiological Records Centre.However, it shouldbe bornein mindthat this is, in someweys, an incompletereport; it is knownthat there are a numberof recordsfor 1994which have not yet beensubmitted (and these will stillbe gratefullyreceived), and a srnallnumber of submittedrecords unfortunately appear have gone astray(e.9. -

TENNIS HOLIDAY CAMPS 30Th May - 18Th August

TENNIS HOLIDAY CAMPS www.gsmleisure.co.uk 30th May - 18th August Fun, games and matches www.gsmleisure.co.uk Contact: [email protected] Tel: 07929 335 246 Booking available by individual days or a full week Ages 5-16yrs old Mini Reds 5-7yrs old 9.00-12.00am £12 per day or £48 per week Mini Masters 8-10yrs old 9.00-1.30pm. £16.50 per day or £66 per week Tennis Pro over 10 yrs old 9.00-1.30pm. £16.50 per day or £66 per week Gifts for full week bookings Please book in advance Rothley Tennis Club Queniborough Tennis Club Off Mountsorrel Lane (behind Syston Rugby Club) (behind the library) Barkby Road Rothley Queniborough Leicestershire Leicestershire LE7 7PS LE7 3FE Two Simple Ways to Book Book Online at www.gsmleisure.co.uk post form to: Tim Stanton, 12 North Street, Rothley, Leicester, LE7 7NN MT WT F FW FW - Full Week please reserve me a Week 1 • 30th May - 2nd Jun space on the Week 2 • 17th Jul - 21st jul (please tick) Week 3 • 24th Jul - 28th Jul Mini Red Week 4 • 31st jul - 4th Aug* Mini Masters Week 5 • 8th Aug - 11th Aug Tennis Pro Week 6 • 14th Aug - 18th Aug Mini Red Full Week £48 • £12 per day Mini Masters Full Week £66 • £16.50 per day Tennis Pro £66 • £16.50 per day Total: * Week 4 will be ran at Queniborough Tennis Club Name: .................................................................................................................................................... Age: ..............................................................D.O.B: ............................................................................. -

Anstey Conservation Area Appraisal

Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area Character Appraisal INTRODUCTION 2 Planning policy context ASSESSMENT OF SPECIAL INTEREST 4 LOCATION AND SETTING HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 4 Origins and development, Archaeological interest, Population SPATIAL ANALYSIS 5 Plan form, Inter-relationship of spaces, Villagescape Key views and vistas, Landmarks CHARACTER ANALYSIS 7 Building types, layouts and uses Key listed buildings and structures, Key unlisted buildings, Coherent groups Building materials and architectural details Parks, gardens and trees, Biodiversity DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST 10 MANAGEMENT PLAN 12 General principles, Procedures to ensure consistent decision-making Enforcement Strategy, Article 4 Direction, General condition Possible buildings for spot-listing, Boundary of the Conservation Area Enhancement opportunities, Economic development and regeneration strategy for the Area Strategy for the management and protection of important trees, greenery and green spaces Monitoring change, Consideration of resources, Summary of issues and proposed actions Developing management proposals, Community involvement, Advice and guidance BIBLIOGRAPHY 16 LISTED BUILDINGS IN BARKBY 16 Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area 1 Character Appraisal - Draft - December 2010 BARKBY AND BARKBY THORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Introduction Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area was designated in May 1976. It covers an area of 46 Hectares, much of which is the large parkland belonging to the Pochin Estate of Barkby Hall. The purpose of this appraisal is to examine the historic development of the Conservation Area and to describe its present appearance in order to assess its special architectural and historic interest. The document sets out the planning policy context and how this appraisal relates to national, regional and local planning policies. -

Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area Character Appraisal

CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area CHARACTER APPRAISAL Designated: 1976 Character Appraisal: 2011 Boundary Amended: 2019 BARKBY AND BARKBY THORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION Planning policy context 8 ASSESSMENT OF SPECIAL INTEREST LOCATION AND SETTING 9 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT Origins and development, Archaeological interest, Population 13 SPATIAL ANALYSIS Plan form, Inter-relationship of spaces, Villagescape Key views and vistas, Landmarks 20 CHARACTER ANALYSIS Building types, layouts and uses Key listed buildings and structures, Key unlisted buildings, Coherent groups Building materials and architectural details Parks, gardens and trees, Biodiversity 27 DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST Threats and weaknesses 29 MANAGEMENT PLAN General principles, Enforcement Strategy, Article 4 Direction, General condition Possible buildings for spot-listing, Boundary of the Conservation Area Enhancement opportunities, Economic development and regeneration strategy for the Area Strategy for the management and protection of important trees, greenery and green spaces Monitoring change, Consideration of resources, Summary of issues and proposed actions Developing management proposals, Community involvement, Advice and guidance 32 BIBLIOGRAPHY 33 LISTED BUILDINGS IN BARKBY BARKBY AND BARKBY THORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Including material from Ordnance Survey digital mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Crown copyright. Licence No 100023558 Aerial photo of Barkby and Barkby Thorpe showing the boundary of the Conervation Area following the 2019 boundary amendment BARKBY AND BARKBY THORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Barkby and Barkby Thorpe in 1903 BARKBY AND BARKBY THORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL INTRODUCTION The Barkby and Barkby Thorpe Conservation Area the special interest of the Conservation Area: spaces and trees, and biodiversity. -

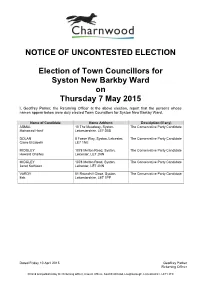

Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Town Councillors for Syston New Barkby Ward on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Geoffrey Parker, the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Town Councillors for Syston New Barkby Ward. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ASMAL 10 The Meadway, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate Mohamed Hanif Leicestershire, LE7 2BD DOLAN 8 Fosse Way, Syston, Leicester, The Conservative Party Candidate Claire Elizabeth LE7 1NE MIDGLEY 1078 Melton Road, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate Howard Charles Leicester, LE7 2NN MIDGLEY 1078 Melton Road, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate Janet Kathleen Leicester, LE7 2NN VARDY 51 Roundhill Close, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate Eric Leicestershire, LE7 1PP Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Geoffrey Parker Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Council Offices, Southfield Road, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 2TX NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Town Councillors for Syston St. Peter`s East Ward on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Geoffrey Parker, the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Town Councillors for Syston St. Peter`s East Ward. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GERRARD 47 Central Avenue, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate Sue Leicestershire, LE7 2EF HAMPSON 80 Main Street, Queniborough, The Conservative Party Candidate Stephen John Leicestershire, LE7 3DA PACEY 1 Pine Drive, Syston, Leicester, The Conservative Party Candidate Maureen Violet LE7 2PZ PEPPER 49 Mostyn Avenue, Syston, The Conservative Party Candidate David Ernest Leicestershire, LE7 2ET WRIGHT 81 High Street, Syston, LE7 1GQ Independent Pat Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Geoffrey Parker Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Council Offices, Southfield Road, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 2TX NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Town Councillors for Syston St. -

The Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2016

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2016 No. 1070 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2016 Made - - - - 8th November 2016 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2), (3) and (4) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009(a) (“the Act”) the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated April 2016 stating its recommendation for changes to the electoral arrangements for the county of Leicestershire. The Commission has decided to give effect to the recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before Parliament and a period of forty days has expired and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act: Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2016. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after this Order is made. (3) Article 3 comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on the day after it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors(c) in 2017. (4) The remainder of this Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on the day after it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2019. Interpretation 2. In this Order “the map” means the map marked “Map referred to in the Leicestershire (Electoral Changes) Order 2016”, held by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England. -

Barkby and Beeby Parish Walks

l31 Cross the stream and continue up the next two 7¼ km (4½ miles), allow fields to meet a farm track. Walk 3: 2 hours, across open Barkby l2 Turn right and follow the track until it eventually countryside, muddy in places This leaflet is one of a series produced to promote becomes4 a footpath across fields. Using the From point B of walk 1, continue down the lane onto circular walking throughout the county. You can obtain waymarkers as a guide, maintain roughly the same Main Street. Barkby others in the series by visiting your local library or direction across open fields and through two small i l At Brooke House Farm turn right following the Tourist Information Centre. You can also order them woods. direction of the fingerpost down the driveway. Walk by phone or from our website. l53 On reaching the metalled road, turn right and to the left of the buildings to eventually cross a stile Bottesford follow the road back to the start point. leading to a track. Take the track up to the road. Muston circular lii Cross the road bearing right to reach another Redmile 3 walks footpath. Once in the field, head diagonally right 1 9¾kms/6 miles aiming for the waymarker in the right hand field 2 5¾kms/3½ miles boundary. Wymeswold Scalford Hathern Burton on the Wolds 3 7¼kms/4½ miles liii Maintain the same direction for the next two fields. Thorpe Acre & Prestwold Asfordby Barrow On reaching the far boundary of the second field turn upon Soar Frisby right, following the waymarkers along the track. -

The Coach House, the Grove, Barkby Lane | Barkby|Leicestershire|LE7 2BB

The Coach House, The Grove, Barkby Lane | Barkby|Leicestershire|LE7 2BB The Coach House, The Grove, Barkby Set in the sought after village of Barkby, and located within the grounds of a former Victorian gentleman's residence. This impressive coach house was converted in 2005 and is finished to the highest standard offering a contemporary feel while retaining the properties original features. The Coach House is accessed via a private tree lined drive accessed by electric security gates. The accommodation briefly consists of an open plan living/ dining area with feature staircase, and a fully fitted Kitchen diner to the ground floor. The first floor offers an impressive master bedroom with en-suite bathroom, and a fabulous mezzanine bedroom with gallery landing. The property also benefits from, Upvc double glazing, electric heating, communal gardens and allocated parking. Internal inspection is a must, properties of this caliber set within rural countryside at this price range rarely come to market. Barkby is an unspoiled, sought after village to the north of Leicester, local amenities including a popular primary school, public house and a cricket ground. The Grove is situated on the outskirts of the village and is only a few a minutes by car from Syston and the Thurmaston Retail Centre where a larger range of local amenities can be found. Barkby offers convenient access to Leicester city, Melton Mowbray, Loughborough and the M1 / M69 motorway network. Ground Floor The Property The property is entered via a double glazed composite door leading into. Living/Dining Area 18' 9'' x 18' 10'' (5.71m x 5.74m)(maximum measurements) Benefiting from Windows to the front, side and rear aspects providing a bright and spacious feel to the heart of the property.