1464640032.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pink Pages Leicester

Pink Pages Leicester Call Pink Pages on 0116 260 00 88 Delivered free to homes and businesses in Thrussington Rearsby, East Goscote, Queniborough, Syston, Barkby Thurmaston Village. Zone 1 - January 2021 www.pink-pages.co.ukPlease mention Pink Pages email: when [email protected] responding to adverts 1 2 To advertise please call 0116 260 00 88 Please mention Pink Pages when responding to adverts 3 Butter�ly Funeral Services Independent Funeral Directors “What the caterpillar perceives as the end, to the Butter�ly is just the beginning” Private Chapel of Rest Pre Paid Funeral Plans Funerals By Shane Mousley Dip FD 0116 269 8120 Day or Night 4 Merchants Common, East Goscote LE7 3XR 4 To advertise please call 0116 260 00 88 Please mention Pink Pages when responding to adverts 5 LEICESTERSHIRE'S CARPET & BED SUPERSTORES We stock 1000’s rolls of carpet and hundreds of mattresses all ready for super quick delivery! We're Leicestershire's BIGGEST hard flooring superstores! Leicestershire's BIGGEST bed stockist, over 150 beds on display. Bring this flyer with you for an extra 5% oo any GET purchase! 5% OFF SEE MORE AT EXCELLENT REVIEWS colourbank.co.uk/testimonials 0116 276 76 60 45 CREST RISE | (OFF ‘LEWISHER RD’) | LE4 9EX LEICESTER *If within 7 days of purchase you find a lower fully fitted price (including fitting, underlay, grippers, strips and del ivery) on any of Colourbank's stock carpets we will refund the difference (proof required) *If within 7 days of purchase you find a Also at lower delivered store price on any of Colourbank's stock beds or mattresses we will refund the difference (proof required) SOP means the price we charge if we don't stock the colour or width shown. -

Welcome to the BMC Travel Guide 2020/21

Welcome to the BMC Travel Guide 2020/21 This guide is for all students, staff and visitors! This guide has been created to provide the very best information for all visitors to Brooksby Melton College, whether this is via public transport, car, bicycle or on foot. As part of a vision which holds sustainability and the environment in mind, here at BMC we are always keen to increase travel choice to our staff, students and visitors. This guide provides information on the transport services available across Melton Mowbray and the Leicestershire area to help students and staff to plan their travel routes to college. BMC is situated on two campuses and is well served by a range of buses and trains which makes for simple and easy access. BMC aims to ensure learning opportunities are available and accessible to all of our students wherever you live. This guide will also help staff members to choose their mode of transport; we hope you find this guide useful, informative and helpful when planning your journey to BMC. Brooksby Hall - Brooksby campus Leicestershire’s Choose How You Move campaign helps people to get fit, save money, have fun and help the environment. For further information visit www.leics.gov.uk/ choosehowyoumove Walking to BMC Walking is a great way to stay healthy, help the environment and save money! Walking to BMC can help you keep fit and healthy. Both campuses benefit from good pedestrian links within the surrounding areas, which allows people to find their way to campus easily and safely. Walking 1 mile in 20 minutes uses as much energy as: Running a mile in 10 minutes Cycling for 16 minutes Aerobics for 16 minutes Weight training for 17 minutes Further information is available from: www.leics.gov.uk/index/highways/passenger_ transport/choosehowyoumove/walking.htm Cycling to BMC Cycling is fun and good for you, so get on your bike! Cycle facilities are provided at both campus; including cycle parking, lockers and changing facilities. -

Draft-Scpc-Minutes-February-2021.Pdf

South Croxton Parish Council Minutes of the Virtual Parish Council Meeting held on Monday 8th February 2021 at 6.00 pm Councillors present: Cllr Dave Morris (Chairman), JoAnn Charles, Cllr Elizabeth Norton In attendance: Clerk – Mr SC Johnson, Member of the public – Vicki Newbery SC18 21 Welcome Cllr Morris opened the meeting and welcomed all present. SC 19 21 Apologies for Absence: Cllr Steve Goodger (No zoom facility), Borough Cllr Daniel Grimley, Cllr Seaton. SC 20 21 Disclosure of Interests and Dispensation by Councillors for this meeting No interests or dispensations were declared at the start of or during the meeting. SC 21 21 Approve by resolution and sign Minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on 11th January 2021 The minutes, circulated before this meeting, were approved by resolution - proposed Cllr Norton, seconded by Cllr Morris, no objections. Clerk to add the minutes to the website and file the copy. SC 22 21 Borough Councillor Report Cllr Daniel Grimley was unable to attend the meeting but had submitted his report which was added to the website prior to the meeting and is attached to these minutes. The main issues raised were Increase of Charnborough share of council tax, Rapid Covid-19 testing available in Loughborough, and a New Grant scheme to help Charnwood businesses affected by Covid-19. SC 23 21 Police Report The February report was received prior to the meeting, was added to the website, and is attached to these minutes. Cllrs have requested that the issue of Hare Coursing be added to the Notice Board and Website and that Cllr Grimley is to be asked to add this information to the Charnwood website. -

Fully Subsidised Services Comments Roberts 120 • Only Service That

167 APPENDIX I INFORMAL CONSULTATION RESPONSES County Council Comments - Fully Subsidised Services Roberts 120 • Only service that goes to Bradgate Park • Service needed by elderly people in Newtown Linford and Stanton under Bardon who would be completely isolated if removed • Bus service also used by elderly in Markfield Court (Retirement Village) and removal will isolate and limit independence of residents • Provides link for villagers to amenities • No other bus service between Anstey and Markfield • Many service users in villages cannot drive and/or do not have a car • Service also used to visit friends, family and relatives • Walking from the main A511 is highly inconvenient and unsafe • Bus service to Ratby Lane enables many vulnerable people to benefit educational, social and religious activities • Many residents both young and old depend on the service for work; further education as well as other daily activities which can’t be done in small rural villages; to lose this service would have a detrimental impact on many residents • Markfield Nursing Care Home will continue to provide care for people with neuro disabilities and Roberts 120 will be used by staff, residents and visitors • Service is vital for residents of Markfield Court Retirement Village for retaining independence, shopping, visiting friends/relatives and medical appointments • Pressure on parking in Newtown Linford already considerable and removing service will be detrimental to non-drivers in village and scheme which will encourage more people to use service Centrebus -

Leicestershire. Galby

DIRECTORY.] LEICESTERSHIRE. GALBY. 83 FROLESWORTH (or Frowlesworlh) is a pleasant from designs by William Bassett Smitb esq. of London, village and parish, 2 miles north from Gllesthorpe station and in 1895 the tower was restored and battlementa and 3 south-west from Broughton Astley station, botb added: the church affords 160 sittings. The register on the Midland railway, 4 west from Ashby Magna dates from the year 1538 and is almost complete. The station, on the main line of the Great Central railway, living is a rectory, net yearly value £290, with residence 4) south-east from Hinckley, 5 north-west from and 57 acres of glebe, in the gift of truste es of the Lutterworth and 92 from London, in the Southern late Rev. Alfred Francis Boucher M.A. and held since division of the county, Guthlaxton hundred, petty 1886 by the Rev. Charles Estcourt Boncher M.A. of sessional division, union and county court district, Trinity Hall, Cambridge, rural dean of Guthlaxton second, of Lutterworth, rural deanery of Guthlaxton (second and master of Smith's ~ almshouses (income £30). Here are portion), archdeaconry of Leicester and diocese of Peter· twenty-four almshouses for widows of the communion of borough. The church of St. Nicholas is a building of the Church of England,founded in 1726 under the will of Chief stone, in the Decorated and Perpendicular styles, with Baron Smith, mentioned abo,·e; the income is now £630 some Early English remains, and consists of chancel, yearly, and each inmate receives £20 yearly: attached to nave, aisles, north porch and a western tower of the the almshouses is a little chapel, in which divine service Decorated period with crocketed pinnacles and contain- is conducted once a week by the rector, who is master of the ing 3 bells, two of which are dated 1638 and 1'749 re- foundation. -

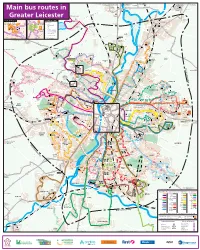

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Ashby Folville Lodge Folville Street | Ashby Folville | Melton Mowbray | Leicestershire | LE14 2TE

Ashby Folville Lodge Folville Street | Ashby Folville | Melton Mowbray | Leicestershire | LE14 2TE YOUR PROPERTY EXPERTS Property at a Glance Situated within approximately 5.7 acres of gardens and parkland on the very edge of this highly desirable village, a substantial six bedroom detached family home of impressive proportions and Substantial Six Bedroom Extended Former Gate Lodge offering four reception rooms and four bathrooms. With a magnificent gated approach, the property was the former gate Energy Rating Pending lodge to Ashby Folville Manor and has been substantially extended over the years and is currently designed to 1.1 Acres of Gardens and Grounds accommodation disabled access with living care through the addition of a self contained annexe and separate living 4.6 Acres of Adjacent Parkland/Paddock accommodation. Requiring general upgrading and modernisation, the property has spectacular views over adjacent Four Reception Rooms parkland, former heated swimming pool and large double garage. Four Bathrooms Large Ground Floor Bedrooms Suite Self Contained Apartment Garaging for Three/Four Vehicles Magnificent Views over Parkland Highly Desirable Village Requiring General Upgrading/Modernisation Potential for One Large Dwelling or to Create Two (Subject to Planning) Offers Over: £600,000 The Property Inner Reception Hall Ashby Folville Lodge is a substantial property in an outstanding rural setting. Originally 17'11" x 10'10" (5.46m x 3.3m) the former gate lodge to Ashby Folville Manor, the property has been substantially With attractive parquet flooring, multi fuel stove with brick surround, stairs to first floor, extended at least twice over the years to create an impressive family home. -

Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire Results

Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire Results Page | 0 Contents 1. Introduction P. 2 2. Questionnaire Methodology P. 2 3. Summary P. 2 4. Results P. 5 Vision for Queniborough in 2028 P. 6 Traffic & Transport P. 9 Facilities & Services P. 15 Housing P. 19 Heritage P. 32 Environment P. 33 Employment & Business P. 42 Anything Else P. 47 5. Appendix 1 – The Questionnaire P. 56 Page | 1 Residents Questionnaire 1) Introduction The Neighbourhood Plan process will provide residents, businesses, service providers and local organisations with a unique opportunity to help guide development within the designated area, plan the future delivery of local services and facilities, and ensure that Queniborough remains a vibrant and sustainable place to live, work, and do business. To support the successful development of the Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan, the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland) supported Queniborough Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group to undertake a consultation with households in the designated area. 2) Questionnaire Methodology A questionnaire was developed by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group in conjunction with the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland). The final version of the questionnaire (see Appendix 1) and the basis of this report, was available for every household. The questionnaire was 16 sides of A4 in length including the instructions, guidance notes providing further background and context and a map of the designated area. Approximately 1500 questionnaires were delivered to households in the designated area during March 2019 by members and volunteers of the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group and included an envelope into which the completed questionnaires could be enclosed, sealed and returned at 3 drop of points around the parish. -

ASHBY FOLVILLE to THURCASTON: the ARCHAEOLOGY of a LEICESTERSHIRE PIPELINE PART 2: IRON AGE and ROMAN SITES Richard Moore

230487 01c-001-062 18/10/09 09:14 Page 1 ASHBY FOLVILLE TO THURCASTON: THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF A LEICESTERSHIRE PIPELINE PART 2: IRON AGE AND ROMAN SITES Richard Moore with specialist contributions from: Ruth Leary, Margaret Ward, Alan Vince, James Rackham, Maisie Taylor, Jennifer Wood, Rose Nicholson, Hilary Major and Peter Northover illustrations by: Dave Watt and Julian Sleap Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and early Anglo-Saxon remains were excavated and recorded during construction of the Ashby Folville to Thurcaston gas pipeline. The earlier prehistoric sites were described in the first part of this article; this part covers three sites with Roman remains, two of which also had evidence of Iron Age activity. These two sites, between Gaddesby and Queniborough, both had linear features and pits; the more westerly of the two also had evidence of a trackway and a single inhumation burial. The third site, between Rearsby and East Goscote, was particularly notable as it contained a 7m-deep stone-lined Roman well, which was fully excavated. INTRODUCTION Network Archaeology Limited carried out a staged programme of archaeological fieldwork between autumn 2004 and summer 2005 on the route of a new natural gas pipeline, constructed by Murphy Pipelines Ltd for National Grid. The 18-inch (450mm) diameter pipe connects above-ground installations at Ashby Folville (NGR 470311 312257) and Thurcaston (NGR 457917 310535). The topography and geology of the area and a description of the work undertaken were outlined in part 1 of this article (Moore 2008), which covered three sites with largely prehistoric remains, sites 10, 11 and 12. -

Rural Grass Cutting III Programme 2021 PDF, 42 Kbopens New Window

ZONE 1 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 1 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 1 30th August - 5th September Primethorpe Broughton Astley Willoughby Waterleys Peatling Magna Ashby Magna Ashby Parva Shearsby Frolesworth Claybrooke Magna Claybrooke Parva Leire Dunton Bassett Ullesthorpe Bitteswell Lutterworth Cotesbach Shawell Catthorpe Swinford South Kilworth Walcote North Kilworth Husbands Bosworth Gilmorton Peatling Parva Bruntingthorpe Upper Bruntingthorpe Kimcote Walton Misterton Arnesby ZONE 2 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 2 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 2 23rd August - 30th August Kibworth Harcourt Kibworth Beauchamp Fleckney Saddington Mowsley Laughton Gumley Foxton Lubenham Theddingworth Newton Harcourt Smeeton Westerby Tur Langton Church Langton East Langton West Langton Thorpe Langton Great Bowden Welham Slawston Cranoe Medbourne Great Easton Drayton Bringhurst Neville Holt Stonton Wyville Great Glen (south) Blaston Horninghold Wistow Kilby ZONE 3 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 3 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 3 16th August - 22nd August Stoughton Houghton on the Hill Billesdon Skeffington Kings Norton Gaulby Tugby East Norton Little Stretton Great Stretton Great Glen (north) Illston the Hill Rolleston Allexton Noseley Burton Overy Carlton Curlieu Shangton Hallaton Stockerston Blaston Goadby Glooston ZONE 4 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. -

June 2013 the Parish of Birstall and Wanlip

JUNE 2013 THE PARISH OF BIRSTALL AND WANLIP 3 PARISH DIARY JUNE—AUGUST 2013 JUNE 2nd 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 16th 6pm Christian Unity Sunday Evensong at Wanlip with Speaker from “GATES” 22nd 9am Coach trip to Gloucester 29/30th Birstall Gala 30th Service on the Park JULY 7th 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 8th—12th Parish Holiday to Cober Hill 27th 10 am Parish Away Day at Nanpantan AUGUST 1st 10 am ‘All Together’ service led by Home Groups 4th 7.30 pm Home Groups Get Together 11th 10 am Mothers’ Union Service 26th 2pm Parish Garden Fete on the Church Lawn Details of our regular services can be found on page 6 Please see church information sheets and/or website www.birstall.org for further information 4 Welcome Welcome to the summer edition of ‘Link’. I hope you find it informative, useful and interesting. It is the first put together ‘under new management’ since our friend - and editor of many years - Maureen Holland died in April. It is due to Maureen’s efforts that ‘Link’ exists today; a link with the Church which we hope to continue to provide you with for a long time to come. Our website editor, Gill Pope, has taken over the production editorial role, Noreen Talbot continues as commissioning editor. Gill and Noreen welcome your contributions as well as your feedback in order to help them make it the magazine that you look forward to receiving and reading each quarter. Thank you for your continued interest in, and support of, the Church. -

THE PARISH and CHURCH of ROTHLEY, LEICESTERSHIRE: a RE-INTERPRETATION Vanessa Mcloughlin

THE PARISH AND CHURCH OF ROTHLEY, LEICESTERSHIRE: A RE-INTERPRETATION Vanessa McLoughlin The following article draws on data gathered, interpreted and recorded in the author’s Ph.D. thesis of 2006 concerning the manor, parish and soke of Rothley, Leicestershire. During her research the author used a combination of historical and archaeological evidence, and concluded that the church at Rothley was a pre- Conquest minster founded in the mid- to late-tenth century. Some of the evidence regarding the church and parish is summarised in this article. Subsequent archaeological evidence has led the author to revise the original proposal, and she now suggests a new date for the foundation of the church at Rothley between the late-seventh and mid-eighth centuries. This foundation can be placed in the context of a Christian mission and the work of bishops, who sought to found bases from which to evangelise and baptise a local population beginning to embrace Christianity. DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE Post-Conquest documentary evidence for Rothley church and parish is readily accessible: for example, the Domesday Book refers to Rothley as a royal holding and records a priest which in turn suggests the presence of a church;1 and the Rolls of Hugh of Wells, circa 1230 (hereafter the Matriculus), record that a vicar was installed at Rothley with chaplains to serve each of the chapels at Gaddesby, Keyham, Grimston, Wartnaby and Chadwell (with Wycomb), and in addition Gaddesby had all the rights of a mother church.2 The Matriculus also recorded that both the