Permanent Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1949-1950

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1949-1950 Eastern Kentucky University Year 1950 Eastern Progress - 10 Mar 1950 Eastern Kentucky University This paper is posted at Encompass. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress 1949-50/9 EASTERN PROGRESS Student Publication of Eastern Kentucky State College Volume 28 Richmond, Kentucky, Friday, March 10, 1950 ' - Numbers' Students Select "Big Three^For 1949-50 Name Choices 125 Earn 40 Points Results of the election held on For First Semester the campus Tuesday, Februapy 21, show that Eastern's favorites One hundred twenty-five stu- arc Jenny Lou Eaves, Doris Cro- dents earned forty or more qual- ley, and Paul Hicks. " ity grade points for the first se- Jenny Lou Eaves, voted Miss mester, 1949-60. They are: Eastern, is an Ashland junior, Donald Meredith Akin, Danville; A Anita Claire Allen, Bardstown; majoring in English and history. Corazon S. Baldos, Manila, Philip- She is a member of the Canter- pines; Nancy Carroll Baldwin, Hop- cury Club, secretary of the House kinsville; William Samuel Bald- Council of Burnam Hall, and was win. Hopkinsville; Dana Lee Ball, k Harlan; John William Ballard, elected this year's ROTC battal- Richmond; Luther Willis Baxter, J ion sponsor. In 1948 Jenny Jr, Lawrenceburg; James Curtis reigned as Snow Queen of the Bevins, Pikevllle; Jack Daris Bil- Christmas formal. As Miss East- lingsley, Middlesboro; Eula Lee Bingham, Burlington; Jack Ken- i ern she will represent the college neth Bradley, McRoberts; Ray at the Mountain Laurel Festival Thomas Brown, Cynthiana; Grigs- to be held at Pineville in May. by Gordon Browning. Dry Ridge, Doris Croley, a senior from In- Richard Lee Browning Cawood; sull, was elected Miss Popularity. -

Top 10 Sa Music 'Media Edia

MUSIC TOP 10 SA MUSIC 'MEDIA EDIA UNITED KINGDOM GERMANY FRANCE ITALY Singles Singles Singles Singles 1 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody/These Are.. (Parlophone) 1 U 96 - Das Boot 1 (Polydor) J.P. Audin/D. Modena - Song Of Ocarina (Delphine) 1 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Sony Music) 2 Wet Wet Wet - Goodnight Girl (Precious) 2 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Sony Music) 2 Patrick Bruel - Qui A Le Droit (RCA) 2 G.Michael/E.John - Don't Let The Sun...(Sony Music) 3 The Prodigy - Everybody In The Place (XL) 3 Salt -N -Pepe - Let's Talk About Sex (Metronome) 3 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Epic) 3 R.Cocciante/P.Turci - E Mi Arriva II Mare (Virgin) 4 Ce Ce Peniston - We Got A Love Thong )ABM) 4 Nirvana - Smells Like Teen Spirit (BMG) 4 Mylene Farmer - Je T'Aime Melancolie (Polydor) 4 Hammer - 2 Legit 2 Quit (EMI) 5 Kiss - God Gave Rock & Roll To ... (Warner Brothers) 5 Monty Python - Always Look On The... (Virgin) 5 Frances Cabrel - Petite Marie (Columbia) 5 D.J. Molella - Revolution (Fri Records) 6 Wonder Stuff - Welcome To The Cheap Seats (Polydor) 6 G./Michael/EJohn - Don't Let The Sun... (Sony Music) 6 Bryan Adams -I Do It For You (Polydor) 6 Bryan Adams -I Do It For You (PolyGram) 7 Kym Sims - Too Blind To See It (east west) 7 Genesis - No Son Of Mine (Virgin) 7Indra - Temptation (Carrere) 7 49ers - Move Your Feet (Media) 8 Des'ree - Feel So High (Dusted Sound) 8 Rozalla - Everybody's Free (Logic) 8 Dorothee - Les Neiges De L'Himalaya (Ariola) 8 LA Style -James Brown Is Dead (Ariola) 9 Kylie Minogue - Give Me A Little (PWL) 9 KLI/Tammy Wynette -Justified.. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Asbestos Removed from Alumnae Hall

CTHE TUFTS DAILY] Medford, MA 02155 Tuesday, March 13,1990 Vol XX, Number 35 Students attend forum on date Asbestos removed rape - and sexual harassment from Alumnae Hall by ALISSA KRINSKY by EMANUEL BARDANIS background air sampling test, a Contributing Writer Daily Editorial Board pump is used to pull air across a Several Tufts organizations and Asbestos removal from Class- filter which is then examined under the Somerville Police Department room 15 in Alumnae Hall that a microscope in order to deter- gave a presentation last Wednes- began on Feb. 27 was completed mine the amount of asbestos in day night on preventing and deal- Friday, according to Lenane But- the atmosphere. ing with date rape and sexual ler, environmental health techni- “We have thoroughly inspected harassment. cian for the Tufts Environmental the campus,” Pitoniak said of an Organizers for the discussion Health and Safety Office. inspection conducted by her of- included the Tufts Police Depart- Construction Project Manager fice a few years ago. She said that ment, the Counseling Center, the John Crow said that the asbestos as a result of that inspection, the Somerville Police Department. removal work on Alumnae Hall Environmental Health and Safety Actively Working for Acquain- is part of current renovation on Office targeted several buildings tance RapeEducation(AWARE), Jackson Gym and Cohen Audito- on campus for asbestos removal. THINK and the Inter-Greek rium, necessitated by the con- “Our long-term goal is to Council Committee on Sexual struction of the Aidekman Arts remove all asbestos from the Harassment and Date RaDe Aware- -1 Center in the lot adjacent to these campus,” Pitoniak said. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Jews, Punk and the Holocaust: from the Velvet Underground to the Ramones – the Jewish-American Story

Popular Music (2005) Volume 24/1. Copyright © 2005 Cambridge University Press, pp. 79–105 DOI:10.1017/S0261143004000315 Printed in the United Kingdom Jews, punk and the Holocaust: from the Velvet Underground to the Ramones – the Jewish-American story JON STRATTON Abstract Punk is usually thought of as a radical reaction to local circumstances. This article argues that, while this may be the case, punk’s celebration of nihilism should also be understood as an expression of the acknowledgement of the cultural trauma that was, in the late 1970s, becoming known as the Holocaust. This article identifies the disproportionate number of Jews who helped in the development of the American punk phenomenon through the late 1960s and 1970s. However, the effects of the impact of the cultural trauma of the Holocaust were not confined to Jews. The shock that apparently civilised Europeans could engage in genocidal acts against groups of people wholly or partially thought of by most Europeans as European undermined the certainties of post-Enlightenment modernity and contributed fundamentally to the sense of unsettlement of morals and ethics which characterises the experience of postmodernity. Punk marks a critical cultural moment in that transformation. In this article the focus is on punk in the United States. We’re the members of the Master Race We don’t judge you by your face First we check to see what you eat Then we bend down and smell your feet (Adny Shernoff, ‘Master Race Rock’, from The Dictators’ The Dictators Go Girl Crazy! [1975]) It is conventional to distinguish between punk in the United States and punk in England; to suggest, perhaps, that American punk was more nihilistic and English punk more anarchistic. -

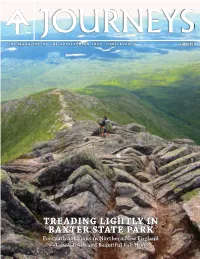

Treading Lightly in Baxter State Park

JOURNEYS THE MAGAZINE OF T HE APPALACHIAN T RAIL CONSERVANCY Fall 2015 TREADING LIGHTLY IN BAXTER STATE PARK Footpath Solutions in Northern New England Take a Brisk and Beautiful Fall Hike JOURNEYS THE M AGAZINE OF T HE A PPALACHIAN TRAIL C ONSERVANCY Volume 11, Number 4 Fall 2015 Mission The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to preserve and manage the Appalachian Trail — ensuring that its vast natural beauty and priceless cultural heritage can be shared and enjoyed today, tomorrow, and for centuries to come. Create Board of Directors A.T. Journeys Sandra Marra ❘ Chair Wendy K. Probst ❘ Managing Editor Greg Winchester ❘ Vice Chair Traci Anfuso-Young ❘ Graphic Designer Elizabeth (Betsy) Pierce Thompson ❘ Secretary Arthur Foley ❘ Treasurer Contributors your legacy Beth Critton Laurie Potteiger ❘ Information Services Manager Norman P. Findley Brittany Jennings ❘ Proofreader On the Cover: Edward R. Guyot Lindsey “Flash Gordon” Gordon heads Mary Higley The staff of A.T. Journeys welcomes with The down the Hunt Trail in Baxter State Park Daniel A. Howe editorial inquiries, suggestions, and comments. after finishing her 2013 thru-hike. Robert Hutchinson Email: [email protected] Photo by John Gordon John G. Noll Colleen T. Peterson Observations, conclusions, opinions, and product Appalachian Rubén Rosales endorsements expressed in A.T. Journeys are those Nathaniel Stoddard of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of members of the board or staff of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. Trail ATC Senior Staff Ronald J. Tipton ❘ Executive Director/CEO Stacey J. Marshall ❘ Senior Director of Advertising Finance & Administration A.T. Journeys is published four times per year. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

No Deadline Set for Faculty Strike Housin: Needs Attended to Over

Serving the college, community for over 50 years Vol. 56 No. 7 William Paterson College September 25, 1989 No deadline set for faculty strike BY BRAD WEISBERGER ner said. The union is ready to president of the local 1796. er 70 percent are limited to a also gives the college presi- NEWS EDITOR strike if neccessary; however The state has offered the ceiling of $44,000 per year, dents sole responsibility for no strike date has been set be- faculty a three-year contract with annual increments, he authorizing the increments, ELIZABETH GUIDE cause the union is hopeful which will freeze all salaries said. The proposed contract SEE STRIKE, PAGE 9 NEWS CONTRIBUTOR that a settlement can be for 18 months. After that, worked out during negotia- there will be a three percent The faculty and staff of tions, she added. However, the increase followed by another WPC may strike in no less faculty will be less likely to three percent increase mid- than two weeks, said Irwiri accept offers because in 1986, way through tfyp third year, Nack, President of the Ameri- the increment system was Radner said. "That would be can Federation of Teachers again an issue and the faculty the equivalent to a one and a (AFT) local 1796. settled on the state's offer. Be- half percent deferred increase In the event no agreements cause of that experience the per year over a two year peri- are made and a strike dead- faculty is not likely to compro- od," Radner said. "They also mise on this issue, Nack said. -

Recording the National Blues

Preacher Boy The National Blues Preacher Boy The National Blues Lyrics by Christopher “Preacher Boy” Watkins (p)2016 PreachSongsMusic/KobaltMusic/BMI (c)2016 Coast Road Records Obituary Writer Blues Cornbread A Person’s Mind Blister and a Bottle Cap My Car Walks On Water There Go John Setting Sun Seven’s In The Middle, Son A Little More Evil Watered Down Down The Drain Obituary Writer Blues began with two things: a visual idea, and a musical one. Visually, it was the parallel imagery of a murdered black body lying on a white sheet, and black letters being laid onto white paper by a writer at a typewriter, charged with drafting an obituary for the murdered. Musically, the song began with a slide riff, borrowed fairly wholesale from Son House, but by way of Will Scott. The thing was then reshaped into a 15-bar cycle—a kind of country blues counting. Two other sections came together later; the 2-chord minor-major interlude, and the chorus, which also quotes from the country blues, borrowing from Sleepy John Estes about knowing right from wrong. The “rock, paper, scissors” image in the final verse came from our daughter, who at the age of 7 has determined that this game is the solution to the problems of violence in the world. I put it in the song because she’s right. obituary writer blues well now, i’m gon’ quit writin’, i’m gonna lay down this pen that i use 2X and you know by that i got them obituary blues well now, i been at that typer lord, honey, ‘til my fingers sore 2X well now, i ain’t gon’ write no obituaries anymore well now, black -

HA!P!Prt NEW Rteajr!?! So Who's Happy?

January 1987 Number24 HA!P!Prt NEW rtEAJR!?! So Who's Happy? December 24, 1986 In Roman days they called thts the Saturnalia: seven days of feasting, drinlctng, and general debauchery that raged, as Dylan Thomas w.ould have it, against thl dying of the ltght. What started out as prayerful suppltcatto1& to th, gods and godusses ended a week later in . an orgy of mindless dissipation, and things have not changed much in the intervening 20 centuries. Saturn was the grandfather of th, gods, and represented the limitations imposed by the physical, mor.tal world. As such he was the appropriatl deity to preside over a festival that commemorated, above all else, human frailty. The Judaeo-Christian version of the Midwinter/est has borrowed much of its imagery from ancient pagan rituals, but then it sho"1dn't take a great deal of insight to realize that the trappings of modern civilization are just that, trappings, and that th, primal impulses of humankind have been only marginally impeded by th, combined efforts of all the .. ___ shamans, witch doctors, priests, and theologians of _____ history. Whln we seek respite from our cares Religion and its modern stepsister, and woes through drinlc, drugs, overeating, or other science, ostensibly operate from a common premise, assassinations of our physical and mental. health, we one best expressed by the words attributed to Jesus confess to ourselves and the world at large that the of Nazareth: HYou shall know th, truth and the truth path of righteousness and/or reason, noble as it may shall make you free. -

Satanstoe; Or, the Littlepage Manuscripts. a Tale of the Colony

SATANSTOE; OR, THE LITTLEPAGE MANUSCRIPTS. A TALE OF THE COLONY. BY J. FENIMORE COOPER. PREFACE. Every chronicle of manners has a certain value. When customs are connected with principles, in their origin, development, or end, such records have a double importance; and it is because we think we see such a connection between the facts and incidents of the Littlepage Manuscripts, and certain important theories of our own time, that we give the former to the world. It is perhaps a fault of your professed historian, to refer too much to philosophical agencies, and too little to those that are humbler. The foundations of great events, are often remotely laid in very capricious and uncalculated passions, motives, or impulses. Chance has usually as much to do with the fortunes of states, as with those of individuals; or, if there be calculations connected with them at all, they are the calculations of a power superior to any that exists in man. We had been led to lay these Manuscripts before the world, partly by considerations of the above nature, and partly on account of the manner in which the two works we have named, "Satanstoe" and the "Chainbearer," relate directly to the great New York question of the day, ANTI-RENTISM; which question will be found to be pretty fully laid bare, in the third and last book of the series. These three works, which contain all the Littlepage Manuscripts, do not form sequels to each other, in the sense of personal histories, or as narratives; while they do in that of principles.