To Inform Tribal Leaders of the Total Resources and Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

Battlefields & Treaties

welcome to Indian Country Take a moment, and look up from where you are right now. If you are gazing across the waters of Puget Sound, realize that Indian peoples thrived all along her shoreline in intimate balance with the natural world, long before Europeans arrived here. If Mount Rainier stands in your view, realize that Indian peoples named it “Tahoma,” long before it was “discovered” by white explorers. Every mountain that you see on the horizon, every stand of forest, every lake and river, every desert vista in eastern Washington, all of these beautiful places are part of our Indian heritage, and carry the songs of our ancestors in the wind. As we have always known, all of Washington State is Indian Country. To get a sense of our connection to these lands, you need only to look at a map of Washington. Over 75 rivers, 13 counties, and hundreds of cities and towns all bear traditional Indian names – Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima, and Spokane among them. Indian peoples guided Lewis and Clark to the Pacifi c, and pointed them safely back to the east. Indian trails became Washington’s earliest roads. Wild salmon, delicately grilled and smoked in Alderwood, has become the hallmark of Washington State cuisine. Come visit our lands, and come learn about our cultures and our peoples. Our families continue to be intimately woven into the world around us. As Tribes, we will always fi ght for preservation of our natural resources. As Tribes, we will always hold our elders and our ancestors in respect. As Tribes, we will always protect our treaty rights and sovereignty, because these are rights preserved, at great sacrifi ce, ABOUT ATNI/EDC by our ancestors. -

September 2013

PPhotoshotos bbyy KKimim RRuthuth aandnd DestineeDestinee ReaRea " Health Care Taxes Liberty rttiioO Economy War HVxyq!&C q Sqqyhq % & C '6xxpsRRxxgGu u$#"e Education in , ColinCol difer Stan irit. rew Standiferor sp , And seni wers,wers Andreheir n Bo ing t Bail-Out Social Sea howingw their senior spirit. ohn, ett s ettijohn,ettij Sean Wil lBo bie P eron , RobbieRob P Cam rphy , and MurphyMu ford,ford and Cameron Willett sho E trick ckelkel rs PatrickPa Sha enio Jake Shac SSeniorsr ald, tzGe SSeniors FFitzGerald,i Jak eni ors sshowho theirAlexAl espiritx Rager at the and fir Marissa P w th Ra S e e ge ir sp r an irit a d Ma t th riss e fir a P sstt ppep assemblyenceence ep a ssem bly. Taxes Liber TThehe MMarchingarching BBulldogulldog BrigadeBrigade putsputs onon theirtheir half-timehalf-time show.show. E TThehe BBulldogulldog cheerleaderscheerleaders ccheerheer tthehe bboysoys Pq qiuq oonn ttoo theirtheir ffourthourth vvictoryictory ooff tthehe sseason.eason. Taxes Liber RRHSHS ccheerleadersheerleaders ppreformreform Economy Wa dduringuring thethe fristfrist ppepep assasseembly.mbly. Education Va SSchoochool Social Securit TradeWho is Educaright for America? Bail-Out SocialaPages Security 12 & 13 $ SSpiritpirit S9PT Health Care Taxes Liberty Meditation practice tthehe H.A.B.I.T ooff SSeptembereptember ! The (health and academics boosted in teens) 22008008 As I sat at my computer screen, agement of one’s thoughts that is smoking and drinking. In a way, BBeste s designed to bring serenity, clarity meditation is the “reset button” for t Beat : I was faced with a blank, white MMontho n t and bliss in every aspect of life. -

© Copyright 2016 William Gregory Guedel

© Copyright 2016 William Gregory Guedel Sovereignty, Political Economy, and Economic Development in Native American Nations William Gregory Guedel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: José Antonio Lucero, Chair Saadia Pekkanen Glennys Young Program Authorized to Offer Degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington Abstract Sovereignty, Political Economy, and Economic Development in Native American Nations William Gregory Guedel Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor José Antonio Lucero The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies The severe and chronic lag in the empirical indicators for Native American socio-economic development has created, in the words of President Obama, “a moral call to action.” Although collective statistics indicate substantial development problems among the 566 federally recognized tribes, these empirical indicators do not manifest uniformly across all Native American nations. This prompts a basic but crucial question: Why are some Native American nations developing more successfully than others? This dissertation examines the theoretical basis and practical applications of tribal sovereignty and presents a new methodology for analyzing the development conditions within Native American nations, utilizing a qualitative assessment of the relative state of a tribe’s formal institutional development and informal institutional dynamics. These foundational elements of the tribal political economy—rather than any specific economic activities—are the prime determinants of a tribe’s development potential. Tribal governments that emphasize the advancement of their institutional structures and the strengthening of citizen cooperation within their communities are more likely to achieve their self-directed development goals, and this paper provides specific examples and recommendations for enhancing sustainable economic development within a tribal political economy. -

King County and Western Washington Cultural Geography, Communities, Their History and Traditions - Unit Plan

Northwest Heritage Resources King County and Western Washington Cultural Geography, Communities, Their History and Traditions - Unit Plan Enduring Cultures Unit Overview: Students research the cultural geographies of Native Americans living in King County and the Puget Sound region of Washington (Puget Salish), then compare/contrast the challenges and cultures of Native American groups in King County and Puget Sound to those of Asian immigrant groups in the same region. Used to its fullest, this unit will take nine to ten weeks to complete. Teachers may also elect to condense/summarize some of the materials and activities in the first section (teacher-chosen document-based exploration of Native American cultures) in order to focus on the student-directed research component. List of individual lesson plans: Session # Activity/theme 1 Students create fictional Native American families, circa 1820-1840, of NW coastal peoples. 2* Students introduce the characters, develop their biographies as members of specific tribes (chosen from those in the Northwest Heritage Resources website searchable database) 3* The fictional characters will practice a traditional art. Research NWHR database to browse possibilities, select one. Each student will learn something about the specific form s/he chose for his/her characters. Students will also glean from actual traditional artists' biographies what sorts of challenges the artists have faced and what sorts of goals they have that are related to their cultural traditions and communities. 4* Cultural art forms: Students deepen their knowledge of one or more art forms. 5 Teacher creates basic frieze: large map of Oregon territory and Canadian islands/ coastal region. -

American Indian Culture and Economic Development in the Twentieth Century

Native Pathways EDITED BY Brian Hosmer AND Colleen O’Neill FOREWORD BY Donald L. Fixico Native Pathways American Indian Culture and Economic Development in the Twentieth Century University Press of Colorado © 2004 by the University Press of Colorado Published by the University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Native pathways : American Indian culture and economic development in the twentieth century / edited by Brian Hosmer and Colleen O’Neill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87081-774-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87081-775-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Economic conditions. 2. Indian business enterprises— North America. 3. Economic development—North America. 4. Gambling on Indian reservations—North America. 5. Oil and gas leases—North America. 6. North America Economic policy. 7. North America—Economic conditions. I. Hosmer, Brian C., 1960– II. O’Neill, Colleen M., 1961– E98.E2N38 2004 330.973'089'97—dc22 2004012102 Design by Daniel Pratt 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents DONALD L. -

Maddra, Sam Ann (2002) 'Hostiles': the Lakota Ghost Dance and the 1891-92 Tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Phd Thesi

Maddra, Sam Ann (2002) 'Hostiles': the Lakota Ghost Dance and the 1891-92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3973/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] `Hostiles':The LakotaGhost Danceand the 1891-92 Tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Vol. II Sam Ann Maddra Ph.D. Thesis Department of Modern History Facultyof Arts University of Glasgow December2002 203 Six: The 1891/92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Dance shovestreatment of the Lakota Ghost The 1891.92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West presented to its British audiencesan image of America that spokeof triumphalism, competenceand power. inside This waspartly achievedthrough the story of the conquestthat wasperformed the arena, but the medium also functioned as part of the message,illustrating American power and ability through the staging of so large and impressivea show. Cody'sWild West told British onlookersthat America had triumphed in its conquest be of the continent and that now as a powerful and competentnation it wasready to recognisedas an equal on the World stage. -

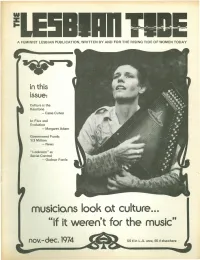

"If It Weren't for the Music"

III Z ~ A FEMINIST LESBIAN PUBLICATION, WRITTEN BY AND FOR THE RISING TIDE OF WOMEN TODAY in this issue: Culture is the Keystone - CasseCuIver In Flux and Evolution - Margaret Adam Government Funds 1/3 Million - News "Looksism" as Social Control - Gudrun Fonta rnoslclons look or culture... "if it weren't for the music" nov.-dec.1974 50 ¢ in L.A. area, 65 ¢ elsewhere 'Ohe THE TIDE COLLECTIVE ADVERTISING VOLUME 4, NUMBER 4 Jeanne Cordova CIRCULATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Barbara Gehrke Dakota EDITORIAL Jeanne Cordova ANNOUNCEr~ENTS 18 Annie Doczi Janie Elven ART! CLES Gudrun Fonfa Kathy Moonstone 3 An Electric Microcosm RO(ji Rubyfruit Lesbian Mothers Fighting Back 7 Robin Morgan; Sisterhood, Inc. Dead 7 Terre Skill-sharing: I Can't Stand It 9 Letter to a Friend 11 FiNANCE, COLLECTIONS & FUNDRAISING Innerview with Arlene Raven 13 Rape Victim Condemned 10 A Lesbian Tide EnNobles Boston 18 Barbara Gehrke CLASSIFIED ADS 19 PHOTOGRAPHY 20 CROSSCURRENTS Kathy Moonstone FROl1 US 8 Sandy P. LETTERS 8 PRODUCTION POETRY Helen H. Ri tua 1 1 6 Sandy P. A Ta 1e in Time 11 Tyler Poem 26 An Anniversary Issue 30 REVIEWS Lavender Jane Loves Women 12 Politics of Linguistics 15 New York Coordinator: Karla Jay ROUNDTABLE: Musicians Look at Culture Culture is the Keystone 4 Cover Design by Sandy P. In Flux and Evolution 4 Keeping Our Art Alive 5 How I See It 5 Photography Credits: New Haven Women's Liberation Rock Band 6 pages 4 & 5, Lynda Koolish; cover, Nina S.; pages 26 & 29, Jeb Graphic Credits: page 17, Rogi Rubyfruit; page 39, Julie H. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 9 STATE OF WASHINGTON; STATE OF NO. 10 OREGON; CONFEDERATED TRIBES OF THE CHEHALIS RESERVATION; COMPLAINT 11 CONFEDERATED TRIBES OF THE COOS, LOWER UMPQUA AND 12 SIUSLAW INDIANS; COW CREEK BAND OF UMPQUA TRIBE OF 13 INDIANS; DOYON, LTD.; DUWAMISH TRIBE; 14 CONFEDERATED TRIBES OF THE GRAND RONDE COMMUNITY OF 15 OREGON; HOH INDIAN TRIBE; JAMESTOWN S’KLALLAM TRIBE; 16 KALISPEL TRIBE OF INDIANS; THE KLAMATH TRIBES; MUCKLESHOOT 17 INDIAN TRIBE; NEZ PERCE TRIBE; NOOKSACK INDIAN TRIBE; PORT 18 GAMBLE S’KLALLAM TRIBE; PUYALLUP TRIBE OF INDIANS; 19 QUILEUTE TRIBE OF THE QUILEUTE RESERVATION; 20 QUINAULT INDIAN NATION; SAMISH INDIAN NATION; 21 CONFEDERATED TRIBES OF SILETZ INDIANS; SKOKOMISH INDIAN 22 TRIBE; SNOQUALMIE INDIAN TRIBE; SPOKANE TRIBE OF 23 INDIANS; SQUAXIN ISLAND TRIBE; SUQUAMISH TRIBE; SWINOMISH 24 INDIAN TRIBAL COMMUNITY; TANANA CHIEFS CONFERENCE; 25 CENTRAL COUNCIL OF THE TLINGIT & HAIDA INDIAN TRIBES 26 OF ALASKA; UPPER SKAGIT COMPLAINT 1 ATTORNEY GENERAL OF WASHINGTON Complex Litigation Division 800 5th Avenue, Suite 2000 Seattle, WA 98104-3188 (206) 464-7744 1 INDIAN TRIBE; CONFEDERATED TRIBES AND BANDS OF THE 2 YAKAMA NATION; AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION; 3 ASSOCIATION OF KING COUNTY HISTORICAL ORGANIZATIONS; 4 CHINESE AMERICAN CITIZENS ALLIANCE; HISTORIC SEATTLE; 5 HISTORYLINK; MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND INDUSTRY; OCA 6 ASIAN PACIFIC ADVOCATES – GREATER SEATTLE; WASHINGTON 7 TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION; and WING LUKE 8 MEMORIAL FOUNDATION D/B/A WING LUKE MUSEUM, 9 Plaintiffs, 10 v. 11 RUSSELL VOUGHT, in his capacity as 12 Director of the OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET; 13 DAVID S. -

Dean Martin I'm Not the Marrying Kind Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Pop Album: I'm Not The Marrying Kind Country: France Released: 1966 Style: Vocal, Easy Listening MP3 version RAR size: 1911 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1581 mb WMA version RAR size: 1869 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 452 Other Formats: MPC FLAC DXD WAV AC3 DTS VQF Tracklist Hide Credits I'm Not The Marrying Kind A 2:03 Written-By – Greenfield*, Schifrin* (Open Up The Door) Let The Good Times In B 2:57 Written-By – Torok*, Redd* Companies, etc. Distributed By – Disques Vogue Credits Arranged By – Bill Justis Producer – Jimmy Bowen Notes French Juke-Box promo Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BIEM Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 0538 Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7") Reprise Records 0538 US 1966 I'm Not The Marrying Kind / Let 0538 Dean Martin The Good Times In (7", Single, Reprise Records 0538 US 1966 Promo) 0538 Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7") Reprise Records 0538 Lebanon 1966 Let The Good Times In / I'm Not R 0538 Dean Martin Reprise Records R 0538 Norway 1967 The Marrying Kind (7") I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7", 0538 Dean Martin Reprise Records 0538 Canada 1966 Single) Related Music albums to I'm Not The Marrying Kind by Dean Martin Dean Martin - I Will Dean Martin - In The Chapel In The Moonlight Dean Martin - Come Running Back / Bouquet Of Roses Dean Martin - The Dean Martin TV Show & Dean Martin Sings Songs From "The Silencers" Marrying M - Marrying Maiden- It's a beautiful day Dean Martin - A Million And One / Shades Dean Martin With The Jimmy Bowen Orchestra & Chorus - Georgia Sunshine Dean Martin - Dean "Tex" Martin Rides Again Dean Martin - Somewhere There's A Someone Dean Martin - A Personal Message From Dean Martin. -

Q4 2018 News Magazine

w w sdukNewsalbix Magazine Issue #2 Winter Quarter 2018 In This Issue: • 20th Anniversary of Re-Recognition • Celebrating Tribal Heritage With The Snoqualmie Valley YMCA • Snoqualmie Welcomes N8tive Vote • And More! Call For Submissions Tribal Member News Here we present to you, the second issue of the new quarterly news magazine. We hope you are enjoying Northwest Native American Basketweavers Association reading the content and seeing the photos that this new, extended magazine format allows us to publish! Linda Sweet Baxter, Lois Sweet Dorman and McKenna Sweet Dorman traveled But as much as we like to write and enjoy creating content, we want this magazine to belong to all Tribal to Toppenish, WA to attend the Northwest Native American Basketweavers Members. If you have a story to tell or an item of news, art or photography you want to share please contact Association’s (NNABA) 24th annual gathering in October. us. We would be very happy to include your material in an upcoming issue of the magazine. They sat with Laura Wong-Whitebear, who was teaching coil weaving with Our e-mail address and our mailing address can be found in the blue box right below this space. You can hemp cord and waxed linen. contact us using either one. Please Welcome Rémy May! Christopher Castleberry and his wife Audrey Castleberry are honored to present their newest family member, Rémy May. Table of Contents sdukwalbixw News Magazine Staff Born on Nov. 27th she is 8lbs 6oz and 20.5 inches tall. Call For Submissions 2 Michael Brunk Here, dad and daughter are pictured at Snoqualmie Falls. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing West: Performances of War and Empire in Pacific Northwest Pageantry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/56q7p336 Author Vaughn, Chelsea Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing West Performances of War and Empire in Pacific Northwest Pageantry A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Chelsea Kristen Vaughn August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Molly McGarry, Chairperson Dr. Catherine Gudis Dr. Jennifer Doyle Copyright by Chelsea Kristen Vaughn 2016 The Dissertation of Chelsea Kristen Vaughn is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Earlier versions of Chapter 3 “Killing Narcissa” and Chapter 4 “The Road that Won an Empire” appeared in the Oregon Historical Quarterly. Research for this dissertation was assisted by the following grants: 2014 History Research Grant, Department of History, University of California, Riverside 2013 Dissertation Year Program Fellowship, Graduate Division, UC, Riverside 2012 History Research Grant, Department of History, University of California, Riverside 2012 Donald Sterling Graduate Fellow, Oregon Historical Society iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Playing West Performances of War and Empire in Pacific Northwest Pageantry by Chelsea Kristen Vaughn Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in History University of California, Riverside, August 2016 Dr. Molly McGarry, Chairperson In April 1917 the United States officially entered a war that it had hoped to avoid. To sway popular sentiment, the U.S. government launched a propaganda campaign that rivaled their armed mobilization.