Canada and the OECD: 50 Years of Converging Interests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 22, 2020 Director General, Telecommunications and Internet

Denis Marquis President, Bell Pensioners' Group 1914, rue Cugnet Saint-Bruno de Montarville QC J3V 5H6 Tel.: 450 441-0111 Email: [email protected] January 22, 2020 Director General, Telecommunications and Internet Policy Branch, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 235 Queen Street, 10th Floor, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H5 Sent via e-mail to: [email protected] Subject: Canada Gazette, Part I, December 14, 2019, Volume 153, Number 10, Notice No. TIPB-002-2019 — Petitions to the Governor in Council concerning Telecom Order CRTC 2019-288 Dear Madam: Attached please find a submission by the Bell Pensioners’ Group (BPG) concerning the above- noted matter. Yours truly, Denis Marquis President, Bell Pensioners’ Group www.bellpensionersgroup.ca Attachment c.c: Hon. Navdeep Bains, P.C., M.P., Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry [email protected] Hon. Deb Schulte, P.C., M.P., Minister of Seniors [email protected] Attachment Canada Gazette, Part I, December 14, 2019, Volume 153, Number 10, Notice No. TIPB-002-2019 — Petitions to the Governor in Council concerning Telecom Order CRTC 2019-288 Comments of the Bell Pensioners’ Group In accordance with Gazette Notice No. TIPB-002-2019, the Bell Pensioners’ Group (BPG) is pleased to provide this submission in support of a petition to the Governor in Council by Bell Canada seeking a variation of a decision issued by the Canadian Radio-television and Tele- communications Commission (CRTC) concerning final rates for aggregated wholesale high- speed internet access services. This CRTC decision requires that facilities-based competitors like Bell Canada (Bell) allow use of their state-of-the-art communications networks by resale- based competitors at substantially reduced prices that are, in the case of Bell, below its costs incurred to build those networks. -

Accession No. 1986/428

-1- Liberal Party of Canada MG 28 IV 3 Finding Aid No. 655 ACCESSION NO. 1986/428 Box No. File Description Dates Research Bureau 1567 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. I July 1981 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Saskatchewan, Vol. I and Sept. 1981 II Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Alberta, Vol. II May 20, 1981 1568 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Manitoba, Vols. II and III 1981 Liberal caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. IV 1981 Elections & Executive Minutes 1569 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings Apr. 29, 1979 to Apr. 13, 1980 Poll by poll results of October 1978 By-Elections Candidates' Lists, General Elections May 22, 1979 and Feb. 18, 1980 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings June-Dec. 1981 1984 General Election: Positions on issues plus questions and answers (statements by John N. Turner, Leader). 1570 Women's Issues - 1979 General Election 1979 Nova Scotia Constituency Manual Mar. 1984 Analysis of Election Contribution - PEI & Quebec 1980 Liberal Government Anti-Inflation Controls and Post-Controls Anti-Inflation Program 2 LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA MG 28, IV 3 Box No. File Description Dates Correspondence from Senator Al Graham, President of LPC to key Liberals 1978 - May 1979 LPC National Office Meetings Jan. 1976 to April 1977 1571 Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John's West (Nfld) Riding Profiles St. John's East (Nfld) Riding Profiles Burin St. George's (Nfld) Riding Profiles Humber Port-au-Port-St. -

September 15-16, 2009 Four More Announce Candidacy Arena Planning Costs by Laureen Sweeney the Environment Committee of West- Mount’S Healthy City Project

WESTMOUNT INDEPENDENT Weekly. Vol. 3 No. 9c We are Westmount September 15-16, 2009 Four more announce candidacy Arena planning costs By Laureen Sweeney the environment committee of West- mount’s Healthy City Project. now exceed $800,000 Four new candidates announced to the Leahey, 44, is in sales and marketing in Independent last week their intention to the high-tech field and is an active volun- By Laureen Sweeney as well as almost $100,000 in unapproved stand for election to Westmount city coun- expenses. teer in Westmount Scouting and other With the date of the new arena/pool in- cil on November 1. They are Victor Drury community programs. He plays hockey “I see it as money well spent,” said in District 3, Georges Hébert and Douglas formation meeting set for September 26, Councillor Tom Thompson in moving the and coaches his sons’ teams. city council approved addi- Leahey in District 5, and Tim Price in Dis- In other districts, Drury, 62, is a profes- motion for the transfer from trict 2. All are running for seats being va- tional funding at its Septem- contingency. sional fundraiser, veteran political organ- ber 8 meeting to cover an cated by incumbents. izer and erstwhile volunteer. He recently New Some of the added fees, he So far, the only contested one is District allocation shortfall for profes- explained, included those for stepped down as CEO of the Foundation sional services related to the 5, now held by George Bowser. This south- of Stars for research into children’s dis- information providing knowledge of the west section of the city is shaping up to be initial project, which now site, validation of costs and de- eases. -

14 ASSIGNMENT # COL07-10 Interviewing Dates: May 3-5/84 GALLUP'vvould Lilce YOUR OPINION Inferv1ewer DON't READ ALOUD

~tklAL # COL03-06 WEEK # COL 14 ASSIGNMENT # COL07-10 Interviewing dates: May 3-5/84 GALLUP'vVOULD LilCE YOUR OPINION INfERV1EWER DON'T READ ALOUD. WOHOS IN CAPITAL LETTERS I CIRCLE APrrW['nlATE NUMlJERS OR CHECK (JOXES 7'85-1 SLGGESTED INTRODUCTION. GooU d:ly, lrn from the Gallup Organiution. and I'd like 10 l:llk 10 you about a rew lopic:s on mllionaJ public ooinion and on nun.ClinC. • SECTION I - ASK EVERYONE: Should he be committed to reduClng government spencing in spite of current high unemployment 1_-__ or should he continue high government spending in order to create jobs? ASK EVERYONE: ,.:.0 1a. Have you heard or read anything about the REDUCE GOVERNMENT SPENDING-----l up-coming Liberal Convention to elect a new Sfr CONTINUE HIGH GOVERNMEN7 SPENDING--2 federal Liberal leader? NEITHER/STAY THE SAME----------------3 YE S- - - 1- J, .. DON'T KNOW-------------~---------------C NO-------2 #115 ~S 2c.~A~n~d~s~hould he lead Canada in the direction of ])K /",s... 3 of socialism, or away from socialism? IN DIRECTION OF SOCIALISM-----l·~1 AWAY FROM SOCIALISM-----------2 ASK EVERYONE: NEITHER/STAY THE SAME---------3 b. Here is a card listing some possible contenders. HAND CARD 1 DON'T KNOW--------------------4 ~ lS J:f you could verte on this , which one of these would you vote for as leader of the federal 2d. Should he be committed to expanding social Liberal Party? welfare programs, or reducing them? EXPANDING SOCIAL WELFARE PROGRAMS---l"~ REDUCING SOCIAL WELFARE PROGRA~S----2 LLOYD AXWORTHY---- 1- J7 NEITHER/STAY THE SAME---------------3 JEAN CHRETIEN------ 2 DON'T KNOW---------------------~----4 DON JOHNSTON------ 3 ~~ ) 5 MARK MACGUIGAN---- 4 JOHN MUNRO--------- 5 3. -

May/June 1984 - Multiculturalism a Tapestry of I

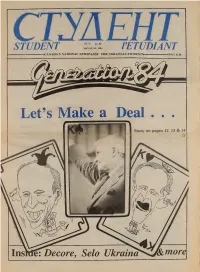

STUDENT ;::. VETUDIANT CANADA'S NATIONAL NEWSPAPER FOR UKRAINIAN STUDENTS PRICE $1.00 Let's Make a Deal . coming musical sensation, DUMKA to In less than two months, the U.B.C. Having heard Ukrainian Students' Club will raise the Vancouver. DUMKA perform at various zabavas and festivals curtain for what is promised to be the best Presidents Message across Canada, I can assure you that they SUSK Congress in history. As someone than adequate repertoire of who has attended four SUSK congresses and have a more and rock music (wait till you hear a countless number of regional conferences, Ukrainian their "Hutzel reggae" stuff!). Of course, after I would like to use this month's column to the zabava, you'll have lots of free time to do entice as many of you as possible to come to Vancouver. as you please.. .anything from taking a mid- night in the Ocean to scaling the Over the past few months, the 25th SUSK dip Congress Committee and your National towering Grouse Mountain! Executive in Ottawa have been workine The Congress social agenda will climax doubly hard to make sure that everything Saturday evening with a group-ouling to one will be perfect for your arrival in of Vancouver's finer restaurants (Vancouver Vancouver. Grants have been secured; has some of the best sea-food available workers have been hired; speakers have been anywhere!) and a cabaret at the U.B.C. confirmed; rooms, accommodations and campus. For those of you who are waiting to meals have been ordered; and all clubs and expose that hidden talent of yours, the Ukrainian youth organizations have been cabaret will be open to anyone eager enough notified of the date and location of the to take the floor (of course, we'll have some congress. -

PIERRE Contents

PIERRE Contents Foreword by Justin Trudeau xi Preface xiii Chapter One: Faith 1 Allan J. MacEachen • Hassan Yassin • B. W. Powe • Michael Higgins • Laurence Freeman • Joseph-Aurele Plourde • Robert Manning • Ron Graham • Nancy Southam Chapter Two: Inside the PMO 31 Jim Coutts • Albert Breton • Jerry Yanover • Joyce Fairbairn • Ralph Coleman • Pierre O'Neil • Bob Murdoch • Roger Rolland • Marc Lalonde • Monique Be'gin • Patrick Gossage • Michael Langill • Joyce Fairbairn • Tim Porteous Chapter Three: On the Road 66 Gabriel Filion • Harrison McCain • Tim Porteous • Victor Irving • Jerry Grafstein • Keith Mitchell • Iona Campagnolo • George Wilson Chapter Four: Just Watching Me 80 Edith Iglauer • George Brimmell • John Fraser • Arnie Patterson • Patrick Nagle • Peter Bregg • Jane Faulkner • Peter Calamai • Geoffrey Stevens • Jerry Yanover • Ralph Coleman • Jim Ferrabee • Patrick Watson Chapter Five: Just Watching Me Too no Victor Irving • Barry Moss • R. H. "Hap" MacDonald • Robert H. Simmonds Chapter Six: Creative Canada 120 Gordon Pinsent • Michael Snow • Jim Harrison • Tim Porteous • Arthur Erickson • June Callwood • Toni Onley • Karen Kain • Catherine McKinnon • Oscar Peterson • Jean-Louis Roux • Christopher Plummer Chapter Seven: 24 Sussex and Harrington Lake 148 Alison Gordon • Joyce Mason • Leslie Kimberley-Kemper • Vicki Kimberley-Naish • Robert H. Simmonds • Heidi Bennet • Claire Mowat • Jane Faulkner • Alastair W. Gillespie Chapter Eight: Notwithstanding Every thing and All of Us 167 Hugh Faulkner • Marc Lalonde • Allan Blakeney • Edward R. Schreyer • Roy McMurtry • Peter Lougheed • Allan Blakeney • Michael Kirby • Judy Erola • Louise Duhamel • Bill Davis Chapter Nine: Longer Views, Differing Angles 187 Conrad Black • Malcolm Fraser • Richard O'Hagan • Jean Chretien • Jean Casselman Wadds • Joe Clark • Gordon Gibson Chapter Ten: Citizen of the World 208 John Kenneth Galbraith • Jonathan Kolber • Ivan Head • Raymond Barre • Roy McMurtry • Gerald Ford • James Callaghan • Brenda Norris • Don Johnston • Jonathan Manthorpe • Matthew W. -

Friday, June 12, 1998

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 121 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, June 12, 1998 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 8087 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, June 12, 1998 The House met at 10 a.m. The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 6 carry? _______________ Some hon. members: Agreed. An hon. member: On division. Prayers (Clause 6 agreed to) _______________ [English] GOVERNMENT ORDERS The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 7 carry? Some hon. members: Agreed. D (1005) An hon. member: On division. [English] (Clause 7 agreed to) CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION AND SAFETY BOARD ACT The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 8 carry? The House resumed from June 10 the consideration in commit- Some hon. members: Agreed. tee of Bill S-2, an act to amend the Canadian Transportation An hon. member: On division. Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act and to make a (Clause 8 agreed to) consequential amendment to another act, Ms. Thibeault in the chair. The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 9 carry? The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 1 carry? Some hon. members: Agreed. Some hon. members: Agreed. An hon. member: On division. An hon. member: On division. (Clause 9 agreed to) (Clause 1 agreed to) The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 10 carry? The Assistant Deputy Chairman: Shall clause 2 carry? Some hon. members: Agreed. Some hon. members: Agreed. An hon. member: On division. -

Rt. Hon. John Turner Mg 26 Q 1 Northern Affairs Series 3

Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes RT. HON. JOHN TURNER MG 26 Q Finding Aid No. 2018 / Instrument de recherche no 2018 Prepared in 2001 by the staff of the Préparé en 2001 par le personnel de la Political Archives Section Section des archives politique. -ii- TABLE OF CONTENT NORTHERN AFFAIRS SERIES ( MG 26 Q 1)......................................1 TRANSPORT SERIES ( MG 26 Q 2) .............................................7 CONSUMER AND CORPORATE AFFAIRS SERIES (MG 26 Q 3) ....................8 Registrar General.....................................................8 Consumer and Corporate Affairs.........................................8 JUSTICE SERIES (MG 26 Q 4)................................................12 FINANCE SERIES (MG 26 Q 5) ...............................................21 PMO SERIES ( MG 26 Q 6)....................................................34 PMO Correspondence - Sub-Series (Q 6-1) ...............................34 Computer Indexes (Q 6-1).............................................36 PMO Subject Files Sub-Series (Q 6-2) ...................................39 Briefing Books - Sub-Series (Q 6-3) .....................................41 LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION SERIES (MG 26 Q 7)..............................42 Correspondence Sub-Series (Q 7-1) .....................................42 1985-1986 (Q 7-1) ...................................................44 1986-1987 (Q 7-1) ...................................................48 Subject Files Sub-Series (Q 7-2)........................................73 -

Friday, February 12, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 180 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, February 12, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 11821 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, February 12, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. strophic for a nation of just eight million. The utter devastation on the lives of those who survived that terrible carnage demanded _______________ action on the home front. Military hospitals, vocational training, re-establishment and job placement were the orders of the day. Prayers Another 45,000 Canadians were lost in the second world war _______________ and, with the anticipated return of one million service men and women, the government at the time recognized that a single GOVERNMENT ORDERS department devoted exclusively to veterans was needed. In 1944 the Department of Veterans Affairs was born. In the D (1000) early years it was the repairing of broken bodies and shattered spirits that took precedence, putting interrupted lives back on track [English] and bringing them back to the country where these heroic men and WAR VETERANS ALLOWANCE ACT women longed to be. For all those suffering permanent injury, disability pensions were guaranteed. Hon. Lucienne Robillard (for the Minister of Veterans Af- fairs and Secretary of State (Atlantic Canada Opportunities Further, for the first time these pensions were given to members Agency), Lib.) moved that Bill C-61, an act to amend the War of the women’s auxiliary forces, the merchant seamen, commercial Veterans Allowance Act, the Pension Act, the Merchant Navy fishermen, Canadian overseas firefighters and other civilian groups Veteran and Civilian War-related Benefits Act, the Department of which contributed to winning the war. -

Manoir Westmount Inc

WESTMOUNT INDEPENDENT Weekly. Vol. 45 No. 6d We are Westmount April 56, 5347 WRC gets first cosmetic The boys of spring ‘patch-up’ closure in 5 years BJ L8GD<<B SI<<B<J seemed like an ideal time to deal with a few cracks that inevitably arise when a Some users of the Westmount recre - new building settles after five years.” ation centre (WRC) were taken by surprise The exercise room, teen centre and last week to find the rinks closed, the Café multi-purpose room remained open, how - Mouton Noir shrouded in painters’ drop ever, and registration for upcoming pro - sheets and access limited to the complex. grams continued at the office (see separate Following the end of the hockey season story below). and before the start of the summer pro - Arena foreman Matthew Ciampini, grams, it was decided to use the week to who came up with the idea, said that “it’s partially close the centre in order to attend much easier to do this type of work when to “minor cosmetic patching and paint - there aren’t people around to touch the ing,” said facilities manager Bruce Stacey. wet paint.” “It’s the first time we’ve closed it for a Some doors were repainted, minor dry - week since we opened,” he said. “This wall cracks plastered and stripping was in - stalled to protect some areas from damage Don’t Miss It by players’ hockey sticks. He said all the work was minor and the café was closed Household hazardous waste collection. off so work could be done above the seat - Westmounters 6-year-old Ben Zelermyer (left) and his brother 9-year-old Max were practising a little Westmount Public Library. -

Peter Mansbridge

www.policymagazine.ca July—August 2019 Canadian Politics and Public Policy The Canadian Idea $6.95 Volume 7—Issue 4 On On June 6, 1919, CN was created by an act of the Parliament of Canada. This year, we celebrate 100 years on the move. It took the best employees, retirees, customers, partners Track and neighbouring communities to make us a world leader in transportation. For our first 100 years and the next 100, we say thank you. for 100 cn.ca Years CNC_191045_CN100_Policy_Magazine.indd 1 19-06-14 10:45 dossier : CNC-191045 client : CN date/modif. rédaction relecture D.A. épreuve à description : EN ad Juin 100% titre : CN & Aboriginal Communities 1 sc/client infographe production couleur(s) publication : On Track for 100 Years 14/06/19 format : 8,5" x 11" infographe : CM 4c 358, rue Beaubien Ouest, bureau 500 Montréal (Québec) H2V 4S6 t 514 285-1414 PDF/X-1a:2003 Love moving Canada in the right direction Together, we’re leading Canadians towards a more sustainable future We’re always We’re committed We help grow We’re connecting connected to the environment the economy communities With free Wi-Fi, phone charging Where next is up to all of us. Maximizing taxpayer We are connecting more than outlets and roomy seats, Making smart choices today value is good for 400 communities across the you’re in for a comfy ride will contribute to a greener your bottom line country by bringing some (and a productive one, too). tomorrow. (and Canada’s too). 4,8 million Canadians closer to the people and places they love. -

Tuesday, February 7, 1995

VOLUME 133 NUMBER 147 1st SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, February 7, 1995 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, February 7, 1995 The House met at 10 a.m. Regrettably, other difficulties with this publication seem to have been the result of an apparent misunderstanding between _______________ the House and the National Archives when the publication was edited. Prayers [English] _______________ An erratum has been prepared for the first edition and will be attached to all remaining copies of the book. A revised second [English] edition is currently under production by the National Archives and members will receive their copies when it is available. PRIVILEGE I believe that these measures will rectify the situation and I SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD thank the hon. member for Kingston and the Islands for bringing this matter to the attention of the House. The Speaker: My colleagues, I wish to comment on the matter brought to the attention of the House by the hon. member _____________________________________________ for Kingston and the Islands on December 7 and 8, 1994. The hon. member explained that a serious omission had been ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS found in a publication entitled ‘‘The Prime Ministers of Canada, 1867 to 1994’’, a document prepared jointly by the House of Commons and the National Archives. Subsequently, other errors [English] and inconsistencies were discovered and communicated to me. GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS The hon. member for Kingston and the Islands was justifiably upset by the omission of references to Kingston and the entry for Mr. Peter Milliken (Parliamentary Secretary to Leader of Sir John A.