Becoming Conscious: the Science of Mindfulness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness and the 12 Steps

mindfulness and the 12 steps with Thérèse Jacobs-Stewart Resting the Mind • Assume a body position where your spine is straight and your body relaxed. • Allow your mind to rest for a few minutes, letting whatever happens-or doesn’t happen-be a part of the experiment. • Relax with whatever arises. • When time is up, ask yourself, “How was that?” (Don’t judge; just review what happened and how you felt.) • The only difference between meditation and the ordinary process of feeling, thinking, feeling, and sensation is the application of the “bare awareness.” Mindfulness Meditation Consciously bring awareness to your here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and self-acceptance. 1 Ways Mindfulness and Meditation Help the Therapist • Offers idea of “strengthening the heart” vs. western psychology’s concept of “self-care.” • Reduces compassion fatigue, renews energy, and counteracts burn-out. • Deepens capacity for a compassionate and non- judging presence. • Increases ability to abide with difficult emotions, offering hope and relief. • Sharpens awareness of therapist’s own reactions. Specific Brain States Correlate with Happiness Brain Activity Associated with Mindfulness Meditation 2 Meditation Changes the Circuitry of the Brain Jacobs-Stewart, Paths Are Made by Walking, 2003 “Meditation training can change the brain and forever alter our sense of well-being.” Richard Davidson Laboratory for Neuroaffective Science University of Wisconsin, Madison 3 Effects of Mindfulness on the Addictive Brain • Enhances neural plasticity. • Reduces activity in the amygdala. • Thickens the bilateral, prefrontal right-insular region of the brain. • Integrates prefrontal regulation and limbic emotion activation. • Builds new neural connections among brain cells for self-observation, optimism, and well-being. -

Reviewers Who Completed a Review During 2001

REVIEWERS LIST The constituency of the ARCHIVES comprises a “university” of often interchangeable writers and readers, students, knowledgeable practitioners, and scholars of medicine and sciences underlying the field of psychiatry. The editors are deeply grateful to the many colleagues listed here for their generous assistance in editorial critique and review. The donation of their special expertise is a necessary contribution on which the intellectual standards in the field heavily depend. Jack D. Barchas, MD Editor Larry Abel Francesc Artigas Chawki Benkelfat Evelyn Bromet James Abelson Robert Asarnow Lisa Berkman Judith S. Brook Anissa Abi-Dargham Wesson Ashford Karen Faith Berman Robert K. Brooner Howard B. Abikoff Boris Astrachan Robert Berman George W. Brown Lyn Y. Abramson Evelyn Attia Greg Berns Marty Bruce T. M. Achenbach S. Avenevoli Wade Berrettini Gerard E. Bruder Kenneth M. Adams Elizabeth Auchincloss Larry E. Beutler Maja Bucan Lawrence E.Adler David Avery Joseph Biederman Robert W. Buchanan Lenard A. Adler Thomas Babor Laura Bierut Kathleen K. Bucholz Nancy E. Adler Nadia Badawi George Bigelow Monte Buchsbaum Ralph Adolphs Alan D. Baddeley Robert Bilder Alan J. Budney George Aghajanian Lee Baer Rene Binder Stephen L. Buka W. Stewart Agras J. Michael Bailey Ray Bingham William E. Bunney Schahram Akbarian Ross J. Baldessarini Niels Birbaumer Audrey Burnam Huda Akil James C. Ballenger Boris Birmaher Barbara J. Burns Hagop S. Akiskal J. Bancroft Donald Black Terry Bush Claude Alain Karen J. Bandeen-Roche D. H. Blackwood Daniel Buysse Marigarita Alegria Deanna M. Barch Jack Blaine William Byne Georgios Alexopoulos John C. Barefoot Helen Blair Simpson Robert P. Cabaj Kimmo Alho Russell A. -

CURRICULUM VITAE AMISHI P. JHA Attention.Miami.Edu Mindfulness.Miami.Edu [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE AMISHI P. JHA attention.miami.edu mindfulness.miami.edu [email protected] Date: July 2021 I. PERSONAL: Name: Amishi P. Jha Current Academic Rank: Professor (Tenured) Primary Department: Psychology College of Arts and Sciences University of Miami Citizenship: USA II. HIGHER EDUCATION: Institutional Degrees University of California, Davis (1998) Ph.D. Psychology University of California, Davis (1995) M.A. Psychology University of Michigan (1993) B.S. Psychology Post-doctoral Training Duke University (1998-2001) Neuroimaging, Functional MRI III. EXPERIENCE Academic Appointments: 2021 Professor, University of Miami Department of Psychology 2010 to 2021 Associate Professor, University of Miami Department of Psychology 2002-2010 Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Center for Cognitive Neuroscience and Department of Psychology Other: 2010 to present Director of Contemplative Neuroscience and Co-Founder Mindfulness Research and Practice Initiative (UMindfulness) University of Miami Curriculum Vitae Amishi P. Jha July 2021 pg. 2 IV. PUBLICATIONS *=First author is trainee of APJ A. Book Jha, A.P. (in press, October 19, 2021). Peak Mind. Harper Collins, New York, NY B. Book chapters 1. Denkova, E., Zanesco, A. P., Morrison, A. B., Rooks, J., Rogers, S. L., & Jha, A. P. (2020). Strengthening attention with mindfulness training in workplace settings. In D.J. Siegel and M.S. Solomon, Mind, Consciousness, and Well-Being (pp. 1-22). Norton. 2. *Morrison, A. B. & Jha, A. P. (2015). Mindfulness, attention, and working memory. In B. D. Ostafin, (Ed.), Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 33-46). Springer. 3. Jha, A. P., Rogers, S. L., & Morrison, A. B. (2014). Mindfulness training in high stress professions: Strengthening attention and resilience. -

Anthony P. Zanesco Education Professional Positions Publications

Anthony P. Zanesco Department of Psychology Email: [email protected] University of Miami 5151 San Amaro Drive, Cox Science Annex, Coral Gables, Florida 33146 Education 2010 – 2017 University of California, Davis Degree: Ph.D. Psychology Advisor: Clifford Saron 2010 - 2012 University of California, Davis Degree: M.A. Psychology Advisor: Clifford Saron 2003 - 2007 University of California, Davis Degree: B.A. Psychology, B.A. Philosophy Professional Positions 2017 – Present Postdoctoral Associate. Dr. Amishi Jha, University of Miami. 2010 – 2017 Graduate Student. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. 2007 – 2010 Junior Specialist. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. 2006 - 2007 Undergraduate Research Assistant. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. Publications MacLean, K.A., Ferrer, E., Aichele, S.R., Bridwell, D.A., Zanesco, A.P., Jacobs, T.L., King, B.G., Rosenberg, E.L., Sahdra, B.K., Shaver, P.R., Wallace, A.B., Mangun, G.R., & Saron, C.D. (2010). Intensive meditation training improves perceptual discrimination and sustained attention. Psychological Science, 21, 829-839. Sahdra, B.K., MacLean, K.A., Ferrer, E., Shaver, P.R., Rosenberg, E.L., Jacobs, T.L., Zanesco, A.P., Aichele, S.R., King, B.G., Bridwell, D.A., Lavy, S., Mangun, G.R., Wallace, B. A., & Saron, C.D. (2011). Enhanced response inhibition during intensive meditation training predicts improvements in self-reported adaptive socioemotional functioning. Emotion, 11(2), 299-312. Jacobs, T.L., Epel, E.S., Lin, J., Blackburn, E.L., Wolkowitz, O.M., Bridwell, D.A., Zanesco, A.P., Aichele, S.R., Sahdra, B.K., MacLean, K.A., King, B.G., Shaver, P.R., Rosenberg, E.L, Ferrer, E., Wallace, B.A., & Saron, C.D. -

An Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION

Thought Without Language: an Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Dean Jaworski Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Neil Tennant, Advisor William Taschek Ben Caplan Copyright by Michael Dean Jaworski 2010 Abstract I defend an account of thought on which non-linguistic beings can be thinkers. This result is significant in that many philosophers have claimed that the ability to think depends on the ability to use language. These opponents of my view note that our everyday understanding of our own cognitive activities qua thought bestows upon those activities the propositional structure of sentences and the inferential norms of public linguistic practice. They hold that our attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings project non-existent structure onto the cognitive activities of those beings, and assess the beings’ activities according to standards to which the beings bear no responsibility. So, despite the complex neural and behavioral activities of many non-linguistic beings, my opponents hold that those beings are not properly described as thinkers. To respond to my opponents successfully, one must not merely cite scientific and folk practices of thought attribution that permit thought to be attributed to some non- linguistic beings. My opponents’ insights might be taken to demonstrate a need to revise those practices, or to treat the attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings made within those practices as instrumentally valuable but technically false. Instead, my strategy is to acknowledge the language-like structure and norms of thought, and show that a non- linguistic being’s cognitive activities might nonetheless have that structure and be subject ii to those norms. -

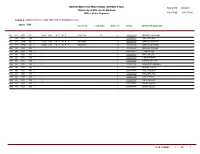

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM SUBJECT: AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMICS (108) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME AGRICULTURALALS AND APPLIED ECONOMICS ACC 306 LEC 001 1 09:00 - 12:00 M T W R 0140 1185 49 6 0000875079 MICHAEL JOHNSON DJJ 399 IND 086 1 - 2 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL ECC 875 SEM 001 2 13:00 - 16:00 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON ECC 875 SEM 001 1 08:30 - 11:30 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON DHH 990 IND 063 1 - 9 0000226384 MICHAEL CARTER DHH 990 IND 064 1 - 1 0002600175 THOMAS COX DHH 990 IND 073 1 - 3 0002601457 IAN COXHEAD DHH 990 IND 078 1 - 3 0002602152 T FORTENBERY DHH 990 IND 079 1 - 1 0002600972 STEVEN DELLER DHH 990 IND 080 1 - 3 0002602096 BRADFORD BARHAM DHH 990 IND 082 1 - 2 0000125075 JEREMY FOLTZ DHH 990 IND 083 1 - 6 0003374884 KYLE STIEGERT DHH 990 IND 086 1 - 1 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL DHH 990 IND 087 1 - 3 0004111956 DAVID LEWIS DHH 990 IND 089 1 - 1 0001459007 SHI GUANMING DHH 990 IND 090 1 - 1 0001016452 BRENT HUETH DHH 999 IND 085 1 - 1 0003088634 BRIAN GOULD PAGE NUMBER: 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:44:48AM SUBJECT: BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING (112) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING DHH 399 IND 010 1 - 2 0000693634 DAVID BOHNHOFF DHH 399 IND 014 1 - 2 0000664097 -

Anthony P. Zanesco Education Professional Positions Publications

Zanesco, August 2019 Anthony P. Zanesco Department of Psychology Email: [email protected] University of Miami 5151 San Amaro Drive, Cox Science Annex, Coral Gables, Florida 33146 Education 2010 – 2017 University of California, Davis Degree: Ph.D. Psychology Advisor: Clifford Saron 2010 - 2012 University of California, Davis Degree: M.A. Psychology Advisor: Clifford Saron 2003 - 2007 University of California, Davis Degree: B.A. Psychology & B.A. Philosophy Professional Positions 2017 – Present Postdoctoral Associate. Dr. Amishi Jha, Department of Psychology, University of Miami. 2010 – 2017 Doctoral Student. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. 2007 – 2010 Junior Specialist. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. 2006 - 2007 Undergraduate Research Assistant. Dr. Clifford Saron, Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis. Publications 1. Shields, G.S., Álvarez-López, M.J., Conklin, Q.A., King, B.G., Zanesco, A.P., Cosín- Tomás, M., Kaliman, P. & Saron, C.D. (under review). Effects of an intensive meditation retreat on the expression of inflammatory and epigenetic- modulatory genes: Downregulation of the TNF-α pathway. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2. Jha, A.P., Zanesco, A.P., Denkova, E., Rooks, J., Morrison, A.B., & Stanley, E.A. Zanesco, August 2019 (under review). Comparing mindfulness and positivity trainings in high- demand cohorts. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 3. Zanesco, A.P., Skwara, A.C., King, B.G., Powers, C., Wineberg, K., & Saron, C.D. (under review). Brain electric microstates and felt states of awareness are modulated by meditation training. Brain Topography. 4. Zanesco, A.P., Witkin, J.E., Morrison, A.B., Denkova, E., & Jha, A.P. -

Curriculum Vitae – D.R

Curriculum Vitae – D.R. Vago March, 2016 DAVID R. VAGO, Ph.D. Harvard Medical School Home Phone: (801) 647-5906 Brigham & Women’s Hospital Office Phone: (617) 732-9113 Department of Psychiatry Fax: (617) 732-9151 75 Francis Street Email: [email protected] Boston, MA 02115 web: www.contemplativeneurosciences.com EDUCATION B.A. 1993-1997 University of Rochester Brain & Cognitive Sciences M.S. 1999-2001 University of Utah Psychology (Cognition & Neural Science) o Thesis: Nicotinic acetylcholine and contextual learning and memory, o Laboratory of Gene Wallenstein, Ph.D. and Raymond Kesner, Ph.D. Ph.D. 2001-2005 University of Utah Psychology (Cognition & Neural Science) o Dissertation: Functional characterization of the direct cortical input to the CA1 subregion of the hippocampus: Electrophysiological and behavioral modulation of the temporoammonic pathway by a non-selective dopamine agonist o Laboratory of Raymond Kesner, Ph.D. Post-doctoral 2005-2007 University of Utah – Utah Center for Exploring Mind-Body Interactions (UCEMBI), Department of Anesthesiology, Pain Research Center, Salt Lake City, UT Post-doctoral 2007-2008 Weill Cornell Medical College, Department of Psychiatry, Functional Neuroimaging Laboratory, New York, NY Post-doctoral 2008-2009 Harvard Medical School–Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Functional Neuroimaging Laboratory, Boston, MA PROFESSONAL POSITIONS 2007-2010 Senior Research Coordinator, Mind and Life Institute, Boulder, CO 2010- Associate Psychologist, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Department -

The Neuroscience of Attention an Interview with Amishi Jha and Ryan Stagg

The Neuroscience of Attention An Interview with Amishi Jha and Ryan Stagg [0:00:08.6] Ryan: Welcome back to the Science of Meditation Summit, today's topic is attention and balancing focus and relaxation. I'm really excited today to be able to have a conversation with Doctor Amishi Jha, who is an associate professor at the University of Miami where her main area of study is attention and she's also involved, really closely, with mindfulness based attention training. So Amishi thank you for taking the time to be with us today. [0:00:37.7] Amishi: Happy to be here. [0:00:39.6] Ryan: So I thought we could start with talking about the critical role of attention, so maybe as someone who's really committed a large part of your life to the study of attention and towards helping people train in attention, you could say what attention is and why it might be so crucial. [0:00:57.6] Amishi: Sure, so in my lab as you mentioned, the University of Miami, I'm a neuroscientist and we study the brain's attention system. We study how it's put together, how different brain networks are involved in allowing us to do this thing called attention as well as what compromises it, what depletes and degrades it. And on the upside of course is how am I able to train attention to protect against its vulnerabilities. And it is, it's a very big system, it's a very powerful system, but doesn't actually fully develop till we're in early adulthood, about the age of twenty five or so. -

5 Th a Nn Iv E Rsa Ry Issu E • T He M Ed Icin Eof Th E M Oment APR IL 2 0 1 8 • Vo Lum E 6, Num Ber 1

5th Anniversary Issue • The Medicine of the Moment APRIL 2018 • volume 6, number 1 number 6, volume • + mindful.org science from our June 2018 issue THE MAGNIFICENT WILD MYSTERIOUS CONNECTED AND INTERCONNECTED BRAIN Our brain is like a wild, raging electrical storm that wondrously enables us to make our way. Yet a lot of mindfulness literature makes it sound like a very simple machine. Two leading neuroscientists suggest better ways to think and talk about the brain and the mind. Illustrations by Aaron Piland 42 mindful June 2018 for more stories like this visit mindful.org science FOR SOME TIME AT MINDFUL, We are in the middle of an epidemic We are in the middle of an epidemic spread we’ve been concerned that discus- spread of BS about the brain. Some- thing new comes up just about every of BS about the brain. Something new sions of the brain—particularly in week that grossly oversimplifies both what science currently knows about comes up just about every week that grossly the context of mindfulness and the brain and how the brain might meditation—have become sim- actually work. Trainers and coaches oversimplifies both what science currently and keynote speakers frequently plified to the point of distorting make extravagant claims about “brain knows about the brain and how the brain the truth. They often present the change,” “growing the brain,” or “adding gray matter.” Forbes recently might actually work. brain as a set of building blocks or published “6 Brain-Based Leader- Lincoln Logs, each with its own ship Game-Changers for 2018,” by an author who writes about “leveraging function. -

Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2018 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness Peter H. Huang University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Citation Information Peter H. Huang, Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness, 7 BRIT. J. AM. LEGAL STUD. 425 (2018), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1237. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 7(2) (2018), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2018-0008 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, And Mindfulness Peter H. Huang* ABSTRACT Spis treści This Article recounts my unique adventures in higher education, including being a Princeton University freshman mathematics major at age 14, Harvard University applied mathematics graduate student at age 17, economics and finance faculty at multiple schools, first-year law student at the University of Chicago, second- and third-year law student at Stanford University, and law faculty at multiple schools. -

Npp2013281.Pdf

Neuropsychopharmacology (2013) 38, S435–S593 & 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/13 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session III-Wednesday participants indicated their ongoing experience of the Wednesday, December 11, 2013 intensity of heartbeat and breathing sensations by rotating a dial. Discrimination was measured by a positive dial deflection above baseline during an infusion trial. Accuracy W2. Interoceptive Awareness in Meditators During was measured via maximum cross correlation between each Cardiorespiratory Deviations in Body Arousal subject’s dial ratings and their corresponding heart rate Sahib Khalsa*, David Rudrauf, Richard Davidson, response. After each infusion participants also traced the Daniel Tranel body locations where they had felt heartbeat sensations, on a manikin template. UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Results: Bolus isoproterenol infusions elicited equivalent Behavior, Los Angeles, California increases in heart rate in both groups (Repeated measures ANOVA; F(1, 5) ¼ 50.1, po0.0001). There were no signifi- Background: Attention directed towards internal body cant group (F(1, 28) ¼ 1.27, p ¼ 0.27) or group x dose sensations is commonly practiced in many meditation interactions (F(1, 5) ¼ 0.04, p ¼ 0.998). There were also no traditions, and is a core skill cultivated when learning group differences in adrenergic sensitivity as measured by mindfulness. This practice is commonly proposed to CD25 (dose required to elevate heart rate by 25 beats per